Human Patterns over Time

The conquest of Middle and South America by Europeans set in motion a series of changes that helped create the ways of life found in this region today. The conquest wiped out much of the indigenous civilizations and set up new societies in their place. Many cultural features from the time of European colonialism endure to this day, as do some vestiges of the precolonial era.

The Peopling of Middle and South America

Recent evidence suggests that between 25,000 and 14,000 years ago, groups of hunters and gatherers from northeastern Asia spread throughout North America after crossing the Bering land bridge on foot, or moving along shorelines in small boats, or both. Some of these groups ventured south across the Central American isthmus, reaching the tip of South America by about 13,000 years ago.

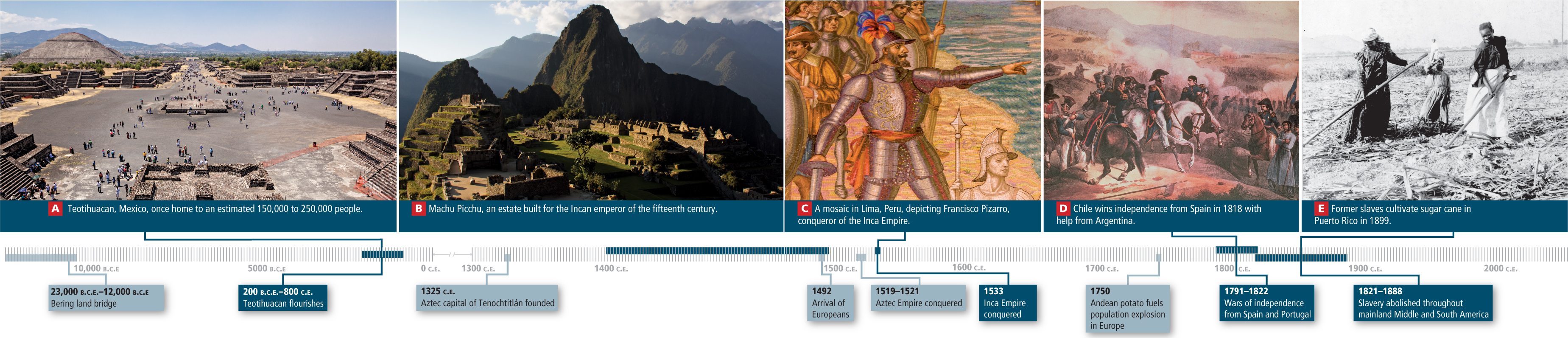

By 1492, there were 50 to 100 million indigenous people in Middle and South America. In some places, population densities were high enough to threaten sustainability. People altered the landscape in many ways. They modified drainage to irrigate crops, they terraced hillsides, and they built paved walkways across swamps and mountains. They constructed cities with sewer systems and freshwater aqueducts, raised huge earthen and stone ceremonial structures that rivaled the pyramids of Egypt (Figure 3.11A).

3.11a Courtesy Bjorn Holland/The Image Bank/Getty Images, 3.11b Courtesy lluís Vinagre/Flickr/Getty Images, 3.11c Courtesy Danita Delimont/Gallo Images/Getty Images, 3.11d Courtesy Spanish School/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images, 3.11e Courtesy M.H. Zahner/Library of Congress

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of Middle and South America, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

How does this image of Teotihuacan lend credence to the idea that as of 1500, relative to their contemporaries in Europe, the Aztecs probably lived more comfortably than did Europeans?

How does this image of Teotihuacan lend credence to the idea that as of 1500, relative to their contemporaries in Europe, the Aztecs probably lived more comfortably than did Europeans?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What about Machu Picchu in the Andean highlands indicates that it was more than a mere summer residence?

What about Machu Picchu in the Andean highlands indicates that it was more than a mere summer residence?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Describe the mood of this depiction of the Spanish conquest of the Incas.

Describe the mood of this depiction of the Spanish conquest of the Incas.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

In what ways does this painting of Creole Argentines and Chileans celebrating independence suggest that they were unlikely to found egalitarian societies?

In what ways does this painting of Creole Argentines and Chileans celebrating independence suggest that they were unlikely to found egalitarian societies?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Even after slavery, who constituted the labor force in sugar cultivation?

Even after slavery, who constituted the labor force in sugar cultivation?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

shifting cultivation a productive system of agriculture in which small plots are cleared in forestlands, the dried brush is burned to release nutrients, and the clearings are planted with multiple species; each plot is used for only 2 or 3 years and then abandoned for many years of regrowth

Aztecs indigenous people of high-central Mexico noted for their advanced civilization before the Spanish conquest

Incas indigenous people who ruled the largest pre-Columbian state in the Americas, with a domain stretching from southern Colombia to northern Chile and Argentina

European Conquest

The European conquest of Middle and South America was one of the most significant events in human history (see Figure 3.11C). It rapidly altered landscapes and cultures and, through disease and slavery, ended the lives of millions of indigenous people.

Columbus established the first Spanish colony in 1492 on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (presently occupied by Haiti and the Dominican Republic). After learning of Columbus’s exploits, other Europeans, mainly from Spain and Portugal on Europe’s Iberian Peninsula, conquered the rest of Middle and South America.

The first part of the mainland to be invaded was Mexico, home to several advanced indigenous civilizations, most notably the Aztecs. The Spanish were unsuccessful in their first attempt to capture the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, but they succeeded a few months later after a smallpox epidemic decimated the native population. The Spanish demolished the grand Aztec capital in 1521 and built Mexico City on its ruins (Figure 3.11A).

A tiny band of Spaniards, again aided by a smallpox epidemic, conquered the Incas in South America. Out of the ruins of the Inca Empire, the Spanish created the Viceroyalty of Peru, which originally encompassed all of South America except Portuguese Brazil. The newly constructed capital of Lima flourished, in large part as a transshipment point for enormous quantities of silver extracted from mines in the highlands of what is now Bolivia.

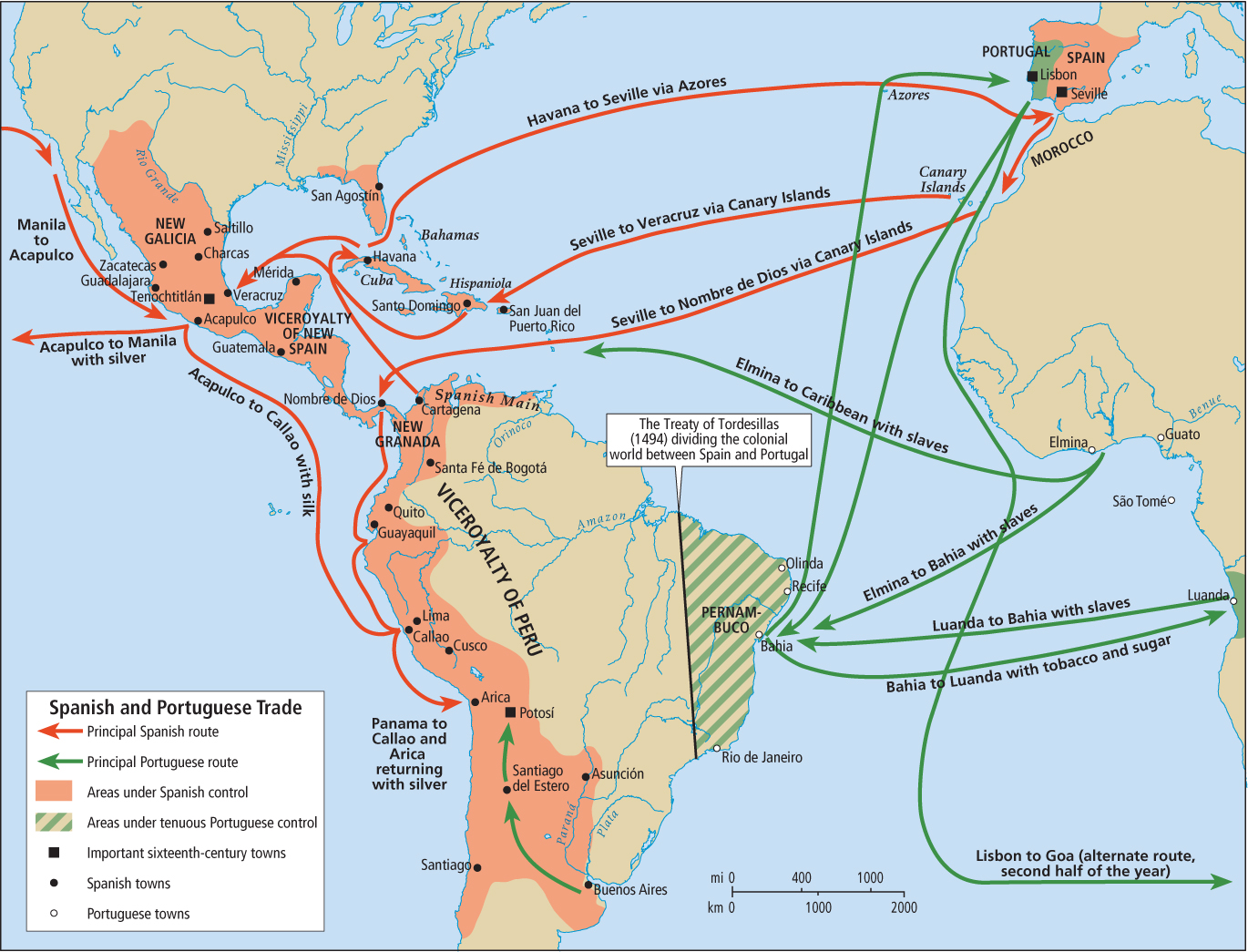

Diplomacy by the Roman Catholic Church prevented conflict between Spain and Portugal over the lands of the region. The Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 divided Middle and South America at approximately 46° W longitude (Figure 3.12). Portugal took all lands to the east and eventually acquired much of what is today Brazil; Spain took all lands to the west.

The superior military technology of the Spanish and Portuguese sped the conquest of Middle and South America. A larger factor, however, was the vulnerability of the indigenous people to diseases carried by the Europeans. In the 150 years following 1492, the total population of Middle and South America was reduced by more than 90 percent to just 5.6 million. To obtain a new supply of labor to replace the dying indigenous people, the Spanish initiated the first shipments of enslaved Africans to the region in the early 1500s.

By the 1530s, a mere 40 years after Columbus’s arrival, all major population centers of Middle and South America had been conquered and transformed by Iberian colonial policies. Figure 3.12 shows how the colonies soon became part of extensive regional and global trade networks, the latter with Europe, Africa, and Asia.

A Global Exchange of Crops and Animals

From the earliest days of the conquest, plants and animals were exchanged between Middle and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia via the trade routes illustrated in Figure 3.12. Many plants essential to agriculture in Middle and South America today—rice, sugarcane, bananas, citrus, melons, onions, apples, wheat, barley, and oats, for example—were all originally imports from Europe, Africa, or Asia. When disease decimated the native populations of the region, the colonists turned much of the abandoned land into pasture for herd animals imported from Europe, including sheep, goats, oxen, cattle, donkeys, horses, and mules.

Just as consequential were plants first domesticated by indigenous people of Middle and South America. These plants have changed diets everywhere and have become essential components of agricultural economies around the globe. The potato, for example, had so improved the diet of the European poor by 1750 that it fueled a population explosion. Manioc (cassava) played a similar role in West Africa. Corn, peanuts, vanilla, and cacao (the source of chocolate) are globally important crops to this day, as are peppers, pineapples, and tomatoes (Table 3.1).

(top) Courtesy Alain Jocard/AFP/Getty Images, (below top) Courtesy Francois Ancellet/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images, (center) Courtesy Louise Heusinkveld/Getty Images, (below center) Courtesy Travis Dove/National Geographic/Getty Images, (bottom) Courtesy Neil Fletcher and Matthew Ward/Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images

The Legacy of Underdevelopment

Creoles people mostly of European descent born in the Caribbean

mestizos people of mixed European, African, and indigenous descent

mercantilism the policy by which European rulers sought to increase the power and wealth of their realms by managing all aspects of production, transport, and commerce in their colonies

Today, the economies of Middle and South America are much more complex and technologically sophisticated than they once were. Nevertheless, disparities persist: About 30 percent of their populations (see Figure 3.11E), the revolutions were of the population is poor and lacks access to land, adequate food, shelter, water and sanitation, and basic education. Meanwhile, a small elite class enjoys levels of affluence equivalent to those of the very wealthy in the United States. These conditions are in part the lingering result of colonial economic policies that favored the export of raw materials and fostered undemocratic privileges for elites and outside investors who often spent their profits elsewhere rather than reinvesting them within the region. These policies will be further discussed in the “Economic and Political Issues” section below.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Shifting cultivation of small plots is a traditional and potentially sustainable agricultural strategy still used by some throughout the region.

Shifting cultivation of small plots is a traditional and potentially sustainable agricultural strategy still used by some throughout the region. Spain and Portugal were the primary colonizing countries of Middle and South America, with smaller colonies held by Britain, France, Denmark, and the Netherlands. By the mid-nineteenth century, most of the larger colonies had gained independence.

Spain and Portugal were the primary colonizing countries of Middle and South America, with smaller colonies held by Britain, France, Denmark, and the Netherlands. By the mid-nineteenth century, most of the larger colonies had gained independence. Exploitative development, incomplete revolutions, a dependence on raw materials exports, and the failure of elites to reinvest profits all led to underdevelopment in this region.

Exploitative development, incomplete revolutions, a dependence on raw materials exports, and the failure of elites to reinvest profits all led to underdevelopment in this region.