4.1 4 Europe

4.1.1 GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS: EUROPE

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS: EUROPE

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Water: Water is an issue in multiple ways. More droughts and floods are likely with climate change. Transportation via water is widespread and energy efficient, but the pollution of rivers and seas, especially the Mediterranean Sea, is increasing. European consumption patterns use virtual water from parts of the world that have deficits of water.

2. Climate Change: The European Union (EU) is a leader in the global response to climate change. Goals to cut greenhouse gas emissions are complemented by many other strategies to save energy and resources.

3. Globalization and Development: As European powers like Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands conquered vast overseas territories, they created trade relationships that transformed Europe economically and culturally and laid the foundation for the modern global economy. Today, Europeans live well, but must struggle to remain globally competitive.

4. Urbanization, Power, and Politics: Rates of urbanization and democratization in Europe are linked, but both rates vary across the region. Northern Europe is the most urbanized (close to 80 percent) and has the most democratic participation. Levels of both urbanization and democratization fall to the south and east.

5. Food: Concerns about food security in Europe have led to heavily subsidized and regulated agricultural systems. Subsidies to agricultural enterprises account for nearly 40 percent of the budget of the European Union. Although large-scale food production by agribusiness is now dominant, there is a revival of organic and small-scale sustainable techniques.

6. Population and Gender: Europe’s population is aging, as working women are choosing to have only one or two children. Immigration by young workers is partially countering this trend.

The European Region

The region of Europe (see Figure 4.1) has played a central role in world history and geography over the last 500 years as a colonizer of distant territories and as a major player in the development of capitalism. Then, in the twentieth century, Europe brought the world to the edge of disaster with two massive wars. Since then it has miraculously revived, prospered, and designed a model for regional trade integration that has been copied in other regions. Europe is now at another important juncture: Can it perfect its union and extend it, or will the union dissolve in the face of growing subregional financial and social disparities? The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Scattered through the chapter, vignettes illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

Grigore Chivu (a pseudonym) wanders through the empty pig pens on his farm near Lugoj in western Romania. For generations, his family has made a meager but rewarding living by raising hogs and then processing and selling the meat. A few years ago, just before Romania joined the European Union (EU), he had more than 250 pigs. At Christmas, he and thousands of pig farmers across the country would slaughter a certain number of their pigs and preserve the meat, using time-honored methods. Pig slaughtering was a time of high spirits, community cooperation, and celebration, as the farmers contemplated the coming feast and their profits. Flavorful sausages, which they smoked and hung high in the rafters of their kitchens for further drying, were slowly parceled out to select customers, providing a steady income well into summer.

When Romania entered the European Union in 2007, all farmers were required to conform to EU standards for processing meat. The old methods were no longer allowed, and for some the new standards were prohibitively expensive.

At first the farmers were uncertain just how to respond. Before they could organize a butchering cooperative that conformed to EU standards, and for which development funds were available, an American company stepped into the breach. Smithfield, a U.S. Fortune 500 meat company based in Virginia, was expanding operations into Central Europe, where it planned to produce pork and pork products on an industrial scale and market them globally, especially in China. Eager to enter the EU market, Smithfield enlisted the help of Romanian politicians and got permission (and even EU subsidies) to establish a conglomerate that included feed production, pig breeding, modernized sanitary barns for fattening thousands of hogs in small cages, and slaughterhouses.

As the old, picturesque Romanian agricultural landscape is transformed into one of huge factory farms, the number of independent pig farmers has been reduced by more than 90 percent (Figure 4.2). Unable to compete with the lower prices Smithfield can charge, Grigore Chivu, like thousands of his fellow pig farmers, was considering migrating to Western Europe where stronger economies meant better-paying jobs. However, because of his age and traditional farming background, Chivu would be eligible for only menial labor. Meanwhile in Romania, he is too young for a pension. [Source: Margareta Lelea; New York Times. For detailed source information see Text Credit pages.]aa

4.2a Courtesy Jeroen Peys/E+/Getty Images, 4.2b Courtesy Andy Sacks/Stone/Getty Images

Thinking Geographically

Question

What about (A) suggests small-scale rearing of pigs?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Grigore Chivu is faced with disruptive change as his country adjusts to new circumstances in the European Union, but he is also part of a global revolution in food production and marketing that is changing food patterns across the world. For example, Smithfield, recently purchased by a Chinese firm, will market pork products, produced and processed at low cost in Romania, to West Africa, where the low prices are putting African pig farmers out of business. A video, Pig Business, explores the many sides of the change from small farm production of hogs to large, corporate farm production. The section on Romania begins at 42 minutes (see http://tinyurl.com/96vh9ja).

European Union (EU) a supranational organization that unites most of the countries of West, South, North, and Central Europe

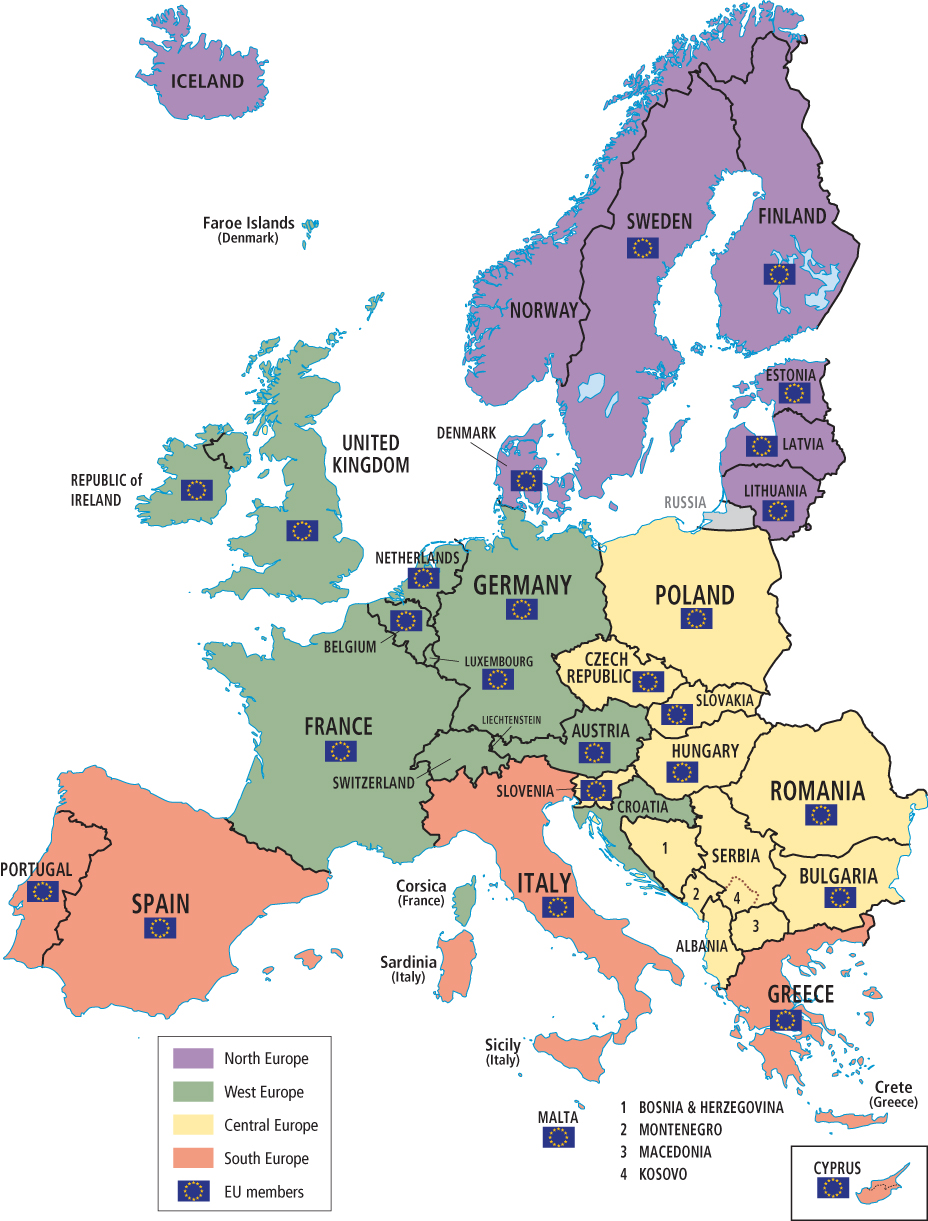

The European Union (EU) is a supranational organization that unites most of the countries of West, South, North, and Central Europe (Figure 4.3). In principle, throughout the European Union, people, goods, and money can move freely. Many people, like Grigore Chivu, decide to migrate only reluctantly, and do so only because poorer regions do not have the political power to push for useful reforms.

There are now 28 countries in the European Union, Croatia being the most recent addition in 2013, with a few more hoping to join in the next several years. The newest members (with the exceptions of Malta and Cyprus) are formerly Communist countries in Central Europe, with lower standards of living and, until the recent EU economic crisis, usually higher unemployment rates than countries in western Europe. As Central European economies faltered, hundreds of thousands of workers from Central Europe took advantage of the EU principle that (theoretically) citizens of any member state may move to any other EU state. More recently, with rising job losses in western Europe, many have returned home.

cultural homogenization the tendency toward uniformity of ideas, values, technologies, and institutions among associated culture groups

Since 2008, the European Union has been under increasing financial stress as a number of less industrialized and less prosperous countries (Greece, for example) have found it so hard to make loan payments that for them national bankruptcy is a possibility. Residents of original and more prosperous EU members—such as France and especially Germany—resent not only having to support these failing economies, but also fear that the migration of workers from the European Union’s south and east is bringing very different people into close contact with each other, resulting in political tensions and increased costs for social and educational services. Others, especially the migrants themselves, lament the cultural homogenization that is wiping out traditional ways. Meanwhile, economic planners and employers across Europe argue that allowing workers to migrate is crucial to Europe’s economic growth and competitiveness on a global scale.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Throughout the European Union, smaller family-run farms are giving way to larger farms run by corporations. This change is strongest in those Central Europe countries that have been recently admitted to the European Union, and has resulted in many farm family members migrating to other EU countries in search of work.

Throughout the European Union, smaller family-run farms are giving way to larger farms run by corporations. This change is strongest in those Central Europe countries that have been recently admitted to the European Union, and has resulted in many farm family members migrating to other EU countries in search of work.