West Europe

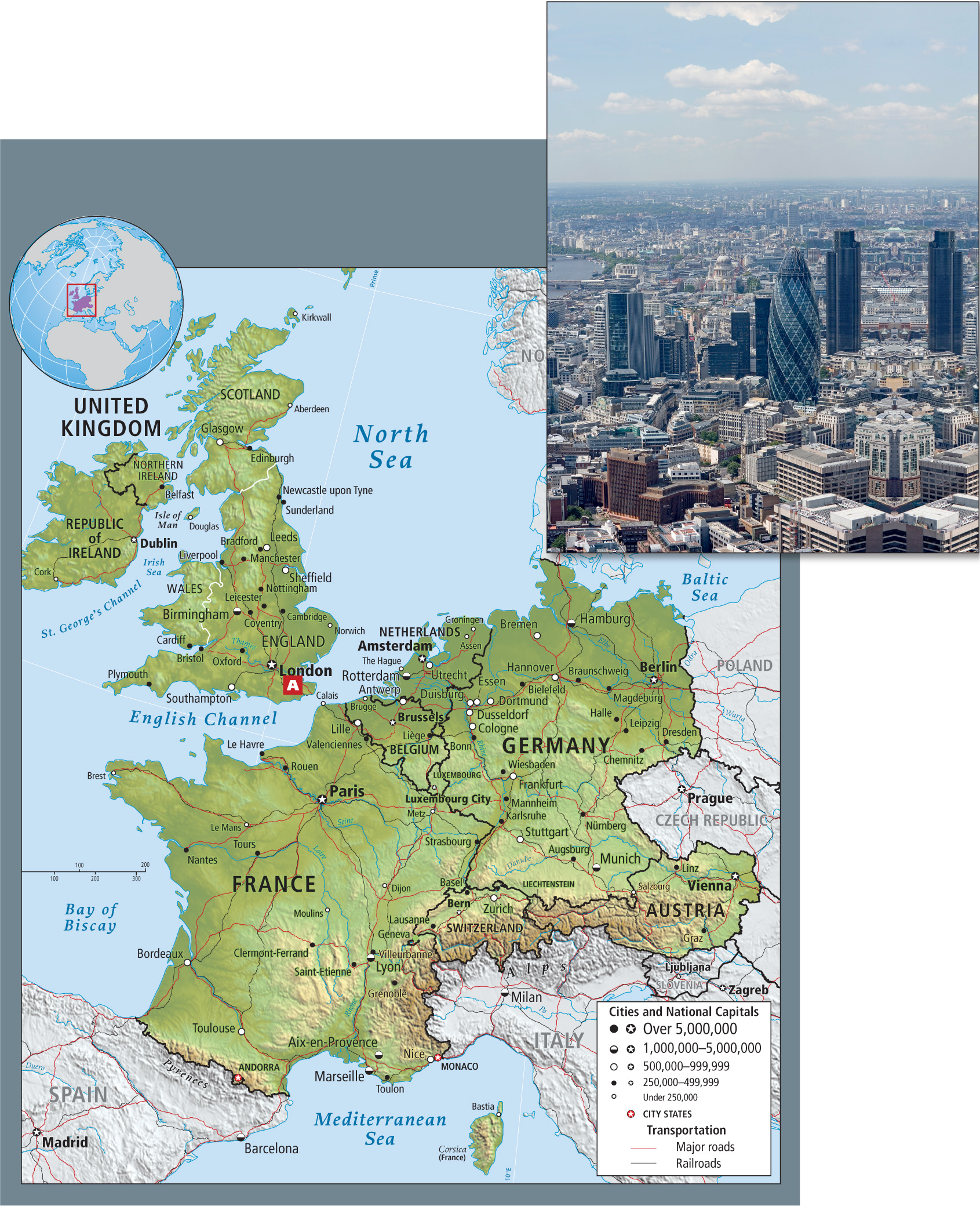

The countries of West Europe (Figure 4.28) include the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, and Switzerland. Despite their economic success, these countries are contending with several issues that will affect their development and overall well-being:

- Challenges to what had been a continual trend toward economic union with each other and with neighboring countries to the north, east, and south.

- Social tensions, such as those generated by the influx of immigrants from inside and outside Europe.

- The persistence of high unemployment despite general economic growth.

- The need to increase the global competitiveness of the subregion’s agricultural, industrial, and service sectors while at the same time maintaining costly but highly valued social welfare programs.

Benelux

Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg—often collectively called the Low Countries or Benelux—are densely populated countries that have very high standards of living (see Figure 4.27). These three countries are well located for trade: they lie close to North Europe and the British Isles and are adjacent to the commercially active Rhine Delta and the industrial heart of Europe. The coastal location of Benelux and its great port cities of Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam give these countries easy access to the global marketplace. Moreover, the Benelux countries have played a central role in the European Union for many years: Brussels, Belgium, is considered the EU capital, with most EU headquarters, along with the NATO headquarters, located there, which also draws other business to Brussels.

International trade has long been at the heart of the economies of Belgium and the Netherlands. Both were active colonizers of tropical zones: Belgium in Africa and the Netherlands in the Caribbean, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Their economies benefited from the wealth extracted from the colonies and from global trade in tropical products such as sugar, spices, cacao beans, fruit, wood, and minerals. Private companies based in Benelux still maintain advantageous relationships with the former colonies, which supply raw materials for European industries. Cacao is an example of this: it is exported from West Africa and imported into Benelux and across Europe for the upscale chocolate industries there.

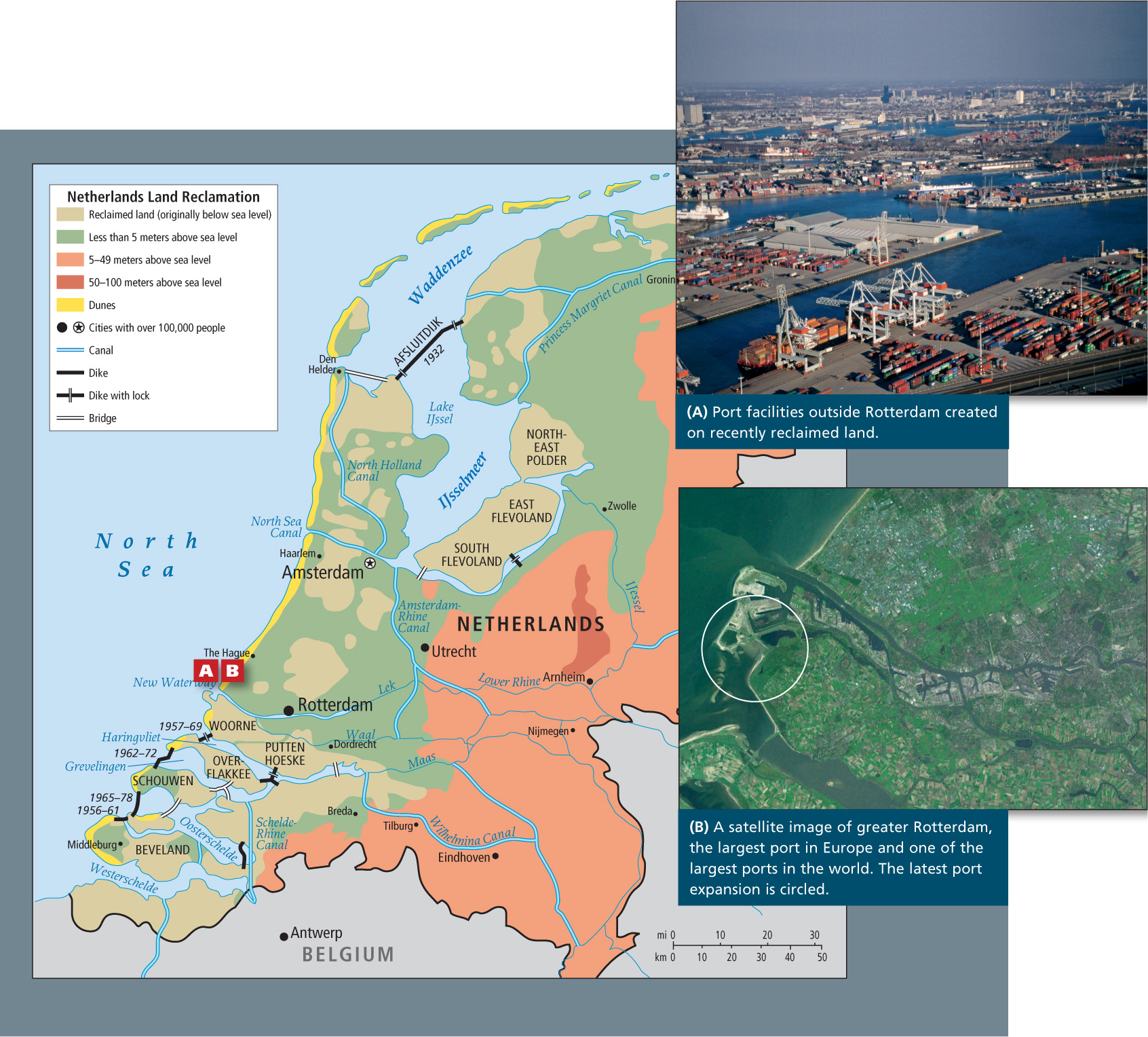

The largest Benelux nation, the Netherlands, is noted particularly for having reclaimed land that was previously under the sea (Figure 4.29A, B and map) and for creating attractive living spaces in wetlands. Today, its landscape is almost entirely a human construct. As its population grew during and after the medieval period, people created more living space by filling in a large, natural coastal wetland. To protect themselves from devastating North Sea surges, they built dikes, dug drainage canals, pumped water with windmills, and constructed artificial dunes along the ocean. Today, a train trip through the Netherlands between Amsterdam and Rotterdam takes one past the port of Amsterdam with lots of ships, fuel storage facilities, and raised rectangular fields crisply edged with narrow drainage ditches and wider transport canals. The fields are filled with commercial flower beds, and one is also likely to see vegetable gardens and grazing cattle, which feed the primarily urban population.

4.29a Courtesy Frans Lemmens/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images, 4.29b Courtesy NASA

Although the Netherlands has a high standard of living, with 16.7 million people, it is the most densely settled country in Europe (with the exception of Malta), and this density has consequences. There is no land left for the kind of high-quality suburban expansion preferred in the Netherlands, without intruding on agricultural space. And there is not nearly enough space for recreation; bucolic as they appear, transport canals and carefully controlled raised fields are not venues for picnics and soccer games. People now travel great distances to reach their jobs, and these long commutes sap time and patience and add to air pollution and traffic jams. Even for weekend getaways, people usually leave the Netherlands for neighboring countries that have more natural areas. The choice to maintain agricultural space is largely a psychological and environmental one, as agriculture accounts for only 2 percent of both the GDP and employment.

France

France is shaped like an irregular hexagon. It is bound by the Atlantic on the north and west, by mountains on the southwest and southeast, by Mediterranean beaches on the south, and by lowlands on the northeast. The capital city of Paris, in the north of the hexagon, is the heart of the cultural and economic life of France. As one of Europe’s two world cities (London is the other), Paris has an economy tied to providing highly specialized services—traditionally, fine food, food processing, fashion, and tourism, but increasingly, accounting, advertising, design, and financial, scientific, and technical services. These service industries draw in a steady stream of workers from Europe and beyond.

Few would quarrel with the idea that French culture has a certain cachet and that France is an arbiter of taste and a model for relaxed urban living. Its magnificent marble buildings, manicured parks, museums, and grand boulevards have made France the leading tourist destination on Earth. In 2011, France attracted a record of 81.4 million tourists, more than the population of the entire country (63.3 million). The countries with the largest increases in visitors to France are Russia, China, and Brazil.

Paris, though elegant, is also a working city. It is the hub of a well-integrated water, rail, and road transportation system, and its central location and transport links attract a disproportionate share of trade and businesses, so it qualifies as a primate city. Together with its suburbs, Paris has more than 12 million inhabitants—roughly one-fifth of the country’s total. In the 1970s, French planners decided that Paris was large enough, and they began diverting development to other parts of the country, especially to Toulouse and farther south to the Mediterranean.

To the west and southwest of Paris (toward the Atlantic) are less densely settled lowland basins that are used primarily for agriculture. France has the largest agricultural output in the European Union; globally, it is second only to the United States in value of agricultural exports. Its climate is mild and humid, though drier to the south. Throughout the country, farmers have found profitable specialties, such as wheat (France ranks fifth in world production), grapes (France and Italy compete for first place in world wine production and wine exports), and cheese (France is second in world production). Despite France’s agricultural leadership, agriculture accounts for only 1.8 percent of the French national GDP (2011) and employs only 3.8 percent of the population. Modernization has made possible ever-higher agricultural production with ever-lower labor inputs. The manufacturing sector, which expanded quickly after World War II, absorbed many former farmworkers; but after 1960, the high-end service sector grew even more rapidly. French industry now (2013) accounts for 18.8 percent of GDP, and services account for nearly 80 percent.

The Mediterranean coast is the site of the French Riviera and France’s leading port, Marseille. Here, development is booming. In part because of all of the tourism to the area, so many marinas, condominiums, and parks have been built that they threaten to occupy every inch of waterfront. The downside of this wealthy, densely populated region is that it produces large amounts of the pollutants that contribute to Mediterranean environmental problems.

France derived considerable benefit and wealth from its large overseas empire, which it ruled until the middle of the twentieth century. Many of the citizens of former French colonies in the Caribbean, North America, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific (and their descendants) now live in France and bring to it their skills and a multicultural flavor. Paradoxically, while the European French are proud of being cosmopolitan, they are also very protective of their distinctive culture and wish to guard what they consider to be its purity and uniqueness. This has led to a marginalization of some (especially Muslim) immigrant minorities, who tend to live on the fringes of the big cities in high-rise apartment ghettos, where they are poorly served by public transportation, have trouble accessing higher education and technical training, and have unemployment rates that are twice the national average.

Many people in France are deeply concerned about what they perceive to be a decrease in France’s world prestige as its industrial competitiveness declines, unemployment rises, social welfare benefits decrease, and traditional French culture is diluted by an influx of migrants from former colonies. Such feelings have resulted in occasional swelling of popular support for the National Front, France’s xenophobic right-wing party. But these tendencies are countered by France’s deep pride in its sophisticated multicultural identity and contribution to an envisioned egalitarian global community. From a purely practical point of view, because it has a low birth rate, France needs immigrants to keep its economy humming, its technology on the cutting edge, and its tax coffers full.

France’s status as a leading member of the European Union rivaled that of Germany for many years. France’s trade volume (imports and exports) remains the sixth largest in the world and it produces at least 25 percent of the EU agricultural products. Recently though, its economic productivity has begun to suffer and its national debt has increased, due in part to expensive social programs and lenient workday rules (the French work only a 35-hour week and have especially generous unemployment benefits). During the EU economic crisis, France paid for an ever-smaller portion of the bailout funds. By late 2012, predictions were that France would itself need a bailout because of constrictions in the manufacturing and service sectors.

Germany

The famous image of a happy crowd in 1989 dismantling the Berlin Wall, as the symbolic end of Soviet influence in Central Europe, had particular significance for Germany. For 40 years, the country had been divided into two unequal parts. At the end of World War II, Russian troops occupied the eastern third of Germany, and by 1949, the Soviets and their German counterparts had turned it into a Communist state known as East Germany. From the beginning, East Germans tried to flee to what was then West Germany. To retain the remaining population, the Soviets literally walled off the border in the summer of 1961. East Germany’s rich resources of skilled labor, minerals, and industrial capacities were used to buttress the socialist economies of the Soviet bloc and to support the military aims of the Soviet Union.

When the Berlin Wall fell and the two Germanys were reunited, East Germany came home with enormous troubles that proved expensive to fix. Its industries were outdated, inefficient, polluting, and in large part irredeemable. Much of its decaying or substandard infrastructure (bridges, dams, power plants, and housing) did not meet the standards of western Europe and had to be remodeled or dismantled and replaced. Its industrial products were not competitive in world markets; East German workers, though considered highly competent in the Soviet sphere, were undereducated and under-skilled by western European standards. Reunified Germany is Europe’s most populous country (82 million people), the world’s fifth-largest economy, and a global leader in industry and trade. But the costs of absorbing the poor eastern zone dragged Germany down in many rankings for years. Unemployment rose sharply (especially among women) in the 1990s and again during the global recession beginning in Europe in 2008. Not only have there been layoffs in the east (where unemployment is nearly double the national average), but workers throughout Germany, accustomed to high wages and generous benefits, are also losing jobs as firms mechanize or move overseas, some to the United States.

During periodic global economic recessions, Germany’s many multinational corporations have an especially difficult time because they are so dependent on global trade in industrial products. Germany has long had the largest export economy in the world ($1.4 trillion in mid-2011), but in 2011 China—of course a far larger country in area and population—overtook Germany, with exports of $1.9 trillion. The automobile industry, centered in Stuttgart, is an example of German commercial ventures that are increasingly moving operations out of Germany to countries, including the United States, where the markets for German cars lie. Expansion into Asia came not only because factory costs are lower there, but also because the market for luxury brands such as Mercedes-Benz is soaring, especially in China. Daimler Trucks, headquartered in Stuttgart, is the world’s largest truck manufacturing company, with plants across Europe and in Africa, Asia, and Brazil. Daimler Trucks North America, now headquartered in Portland, Oregon, is North America’s largest manufacturer of heavy-duty trucks.

Because Germany was regarded as the instigator of two world wars, for years West Germany had to tread a careful path. It had to see to its own economic and social reconstruction, and to rebuilding a prosperous industrial base, without appearing to become too powerful economically or politically. For the most part, West Germany played this complex role successfully. Since the early 1980s, it has been a leader in building the European Union; with the EU’s largest economy, it has borne the greatest financial burden of the European unification process. This burden has only increased during the current economic crisis, and it is the German people who have provided a majority of the funds used to assist Ireland, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. Germany’s leading role in the European Union has positioned Berlin to be highly attractive to Europe’s young adults. Figure 4.30 shows rollicking Sunday afternoon social life in 2012, along the old route of the once infamous Berlin Wall.

The British Isles

The British Isles, located off the northwestern coast of the main European peninsula, are occupied by two countries: (1) the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales) and Northern Ireland—often called simply Britain or the United Kingdom (U.K.); and (2) the Republic of Ireland (not to be confused with Northern Ireland; see also Figure 4.28).

The Republic of IrelandThe main physical resources in the Republic of Ireland (usually called simply Ireland) are its soil, abundant rain, and beautiful landscapes. Ireland’s considerable human capital remained underdeveloped for centuries during and after the time it served as a test-case colony where Britain could hone the technique of mercantilism soon to be used in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa. The British confiscated land for their own use and for the use of their local sympathizers; thus, large numbers of Irish people were turned into landless and starving paupers. When they protested, they were imprisoned or sent as indentured labor to the new Caribbean colonies of the 1600s. Into the modern era, the Irish depended on small-plot agriculture and eventually on tourism, while industrialization lagged. As a result, until very recently, the Irish people were the poorest in West Europe. Over the last two centuries, some 7 million Irish emigrated to find a better life. In the 1990s, however, a remarkable turnaround began. Ireland attracted foreign manufacturing companies by offering cheap, educated labor, accessible air transport, access to EU markets, low taxes, and other financial incentives. The economy grew so quickly that for a time Irish labor was in short supply and the unemployment rate was 1 percent.

To supply the workers required, Ireland invited back those who had emigrated and recruited other foreign workers from many locales, especially the former Soviet satellites (e.g., Latvia and Poland) now in the European Union. In 2000, approximately 42,000 people immigrated to Ireland, 18,000 of whom were returning emigrants, including some information technology (IT) workers from the United States. Czech workers packed Irish meat; Filipino nurses worked in most Irish hospitals. The cost of living rose sharply, however, and this rise plus the global recession meant that Ireland was no longer able to attract or even retain foreign investment. Ireland originally had not favored the admission of Central European countries to the European Union because it feared those countries would attract investment away from Ireland by offering skilled but even cheaper labor pools. This was beginning to happen by 2007. Nevertheless, until the global recession of 2008, Ireland had one of Europe’s fastest-growing (though still small) economies, and industry in Ireland played nearly as important a role as services in the country’s GNI. In 2007, Ireland had Europe’s second-highest per capita GNI, but by the end of 2011, its unemployment rate was 15 percent, affecting 400,000 workers across the skills spectrum. Thousands of guest workers returned to Central Europe, and tens of thousands of native Irish left to other parts of the European Union, to North America, Australia, and New Zealand, leaving behind mortgages they could no longer afford. A banking crisis and rising government debt left Ireland in need of a bailout that amounted to €85 billion (U.S.$108 billion) from the European Union and the IMF, including more than 12 billion pounds (U.S.$19.3 billion) from the United Kingdom. By 2012 Ireland was beginning to rebound; its belt tightening was being recommended as a model for Greece, Spain, and others.

Northern IrelandNorthern Ireland consists of six counties in the northeastern corner of the island; it is distinct from the Republic of Ireland and is administratively part of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland began to emerge as a political entity in the 1600s, when Protestant England conquered the whole of Catholic Ireland. England removed or killed many of the indigenous people and settled Lowland Scots and English farmers on the vacated land. The remaining Irish resisted English rule with guerrilla warfare for nearly 300 years, until the Republic of Ireland gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1921. Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom. Here, Protestant majorities held political control, and the minority Catholics were subject to severe economic and social discrimination. Catholic nationalists unsuccessfully lobbied by constitutional (peaceful) means for a united Ireland. Other Catholic groups, the most radical among them being the Irish Republican Army (IRA), resorted to violence, including terrorist bombings, often against civilians and British peacekeeping forces, who were seen as supporting the Protestants. The Protestants reciprocated with more violence. By 1995, more than 3000 people had been killed in the Northern Ireland conflict or by violence that spread to the United Kingdom.

In 1998, tired of seeing the development of the entire island—and especially of Northern Ireland—blighted by the persistent violence, the opposing groups finally reached a peace accord known as the Good Friday Agreement, which was overwhelmingly approved by voters in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The plan for Northern Ireland provides for more self-government shared between Catholics and Protestants, the creation of human rights commissions, the early release of convicted terrorist prisoners, the decommissioning of paramilitary forces (such as the IRA), and the reform of the criminal justice system. Since 1998, violence has periodically risen and then abated, and the society has slowly begun to accept peaceful coexistence. The city of Belfast remains largely divided along religious lines, but some neighborhoods are beginning to integrate (see Figure 4.13C).

The United KingdomThe United Kingdom consists of England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and 14 of what are known as British Overseas Territories, remnants of the British Empire. Scotland, one of the four main parts of the U.K., is now considering separating from the U.K. administratively, but this separation has not gained widespread popular support in Scotland. The United Kingdom has a mild, wet climate (thanks to the North Atlantic Drift) and a robust agricultural sector that is based on grazing animals. Its usable land is extensive, and its mountains contain mineral resources, particularly coal and iron. In contrast to Ireland, the United Kingdom has been operating from a position of power for many hundreds of years. Beginning in the seventeenth century, Britain added to its own resources those from its colonies, first in Ireland and then in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Together, these resources were sufficient to make Britain the leader of the Industrial Revolution in the early eighteenth century. By the nineteenth century, the British Empire covered nearly a quarter of the world’s land surface. As a result, British culture was diffused far and wide, and English became the lingua franca of the world.

Britain’s widespread international affiliations, set up during the colonial era, positioned it to become a center of international finance as the global economy evolved. Today, London is the leading global financial center, handling more value in financial transactions than New York City, its closest rival. This remains true despite the U.K.’s rejection of the euro (€); that the United Kingdom continues to use the pound (£) may have helped the U.K.’s economy during the EU crisis. The United Kingdom is no longer Europe’s industrial leader, however. At least since World War II, and some say earlier, the United Kingdom has been sliding down from its high rank in the world economy toward the position of an average European nation. The discovery of oil and gas reserves in the North Sea gave the United Kingdom a cheaper and cleaner source of energy for industry than the coal on which it had long depended, but this did not stop the economic decline. Cities such as Liverpool and Manchester in the old industrial heartland and Belfast in Northern Ireland have had long depressions.

Britain has successfully established technology industries in parts of the country that previously were not industrial—for example, near Cambridge and west of London, in a region called Silicon Vale. The service sector currently dominates the economy (accounting for 78 percent of the GDP and 80 percent of the labor force). In the last decade, new, though not high-paying, jobs have been created in health care, food services, sales, financial management, insurance, communications, tourism, and entertainment. Even the movie industry has discovered that England is a relatively cheap and pleasant place for film editing and production. Britain’s past experience with a worldwide colonial empire has left it well positioned to provide superior financial and business advisory services in a globalizing economy. Such service jobs, however, tend to go to young, educated, multilingual city dwellers, many of them from elsewhere in the European Union, not to the middle-aged, unemployed ironworkers and miners left in the old industrial U.K. heartland. Because of the EU’s open borders, there are now more than 400,000 foreign nationals working in Greater London alone.  81. AS EUROPE UNITES, MIGRANT WORKERS SPREAD

81. AS EUROPE UNITES, MIGRANT WORKERS SPREAD

The Jamaican poet and humorist Louise Bennett used to joke that Britain was being “colonized in reverse.” She was referring to the many immigrants from the former colonies who now live in the United Kingdom. Indeed, it would be hard to overemphasize the international spirit of the U.K. London, for example, has become an intellectual center for debate in the Muslim world. Salman Rushdie, the controversial Indian Muslim writer, lives there; many bookstores carry Muslim literature and political treatises in a variety of languages; Israelis and Palestinians talk privately about peace; descendants of Indian and Bangladeshi immigrants run popular restaurants; and Saudi Arabians have a strong presence. A leisurely stroll through London’s Kensington Gardens reveals thousands of people from all over the Islamic world who now live, work, and raise their families in London. They are joined by many other people from the British Commonwealth—Indian, Malaysian, African, and West Indian families—pushing baby carriages and playing games with older children. Impromptu soccer games may have team members from a dozen or more countries.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Globalization and Development Colonialism transformed Europe economically and culturally; but today, Europe is not only struggling to remain globally competitive, it is struggling to find a way to absorb immigrants from former colonies.

Globalization and Development Colonialism transformed Europe economically and culturally; but today, Europe is not only struggling to remain globally competitive, it is struggling to find a way to absorb immigrants from former colonies. Despite their long-term economic success, the countries of West Europe face several issues that affect their citizens’ well-being: the persistence of high unemployment; social tensions caused in part by the influx of immigrants; and the need to continue to increase global competitiveness while maintaining costly but highly valued social welfare programs.

Despite their long-term economic success, the countries of West Europe face several issues that affect their citizens’ well-being: the persistence of high unemployment; social tensions caused in part by the influx of immigrants; and the need to continue to increase global competitiveness while maintaining costly but highly valued social welfare programs. The economic crisis in the European Union has resulted in the countries of West Europe being called upon to contribute to the financial support of other countries with failing economies. Germany has borne the greatest burden.

The economic crisis in the European Union has resulted in the countries of West Europe being called upon to contribute to the financial support of other countries with failing economies. Germany has borne the greatest burden. There is great diversity in the subregion’s many large cities, but in places like Northern Ireland ethnically similar people are still struggling over religious and cultural issues.

There is great diversity in the subregion’s many large cities, but in places like Northern Ireland ethnically similar people are still struggling over religious and cultural issues.