Central Europe

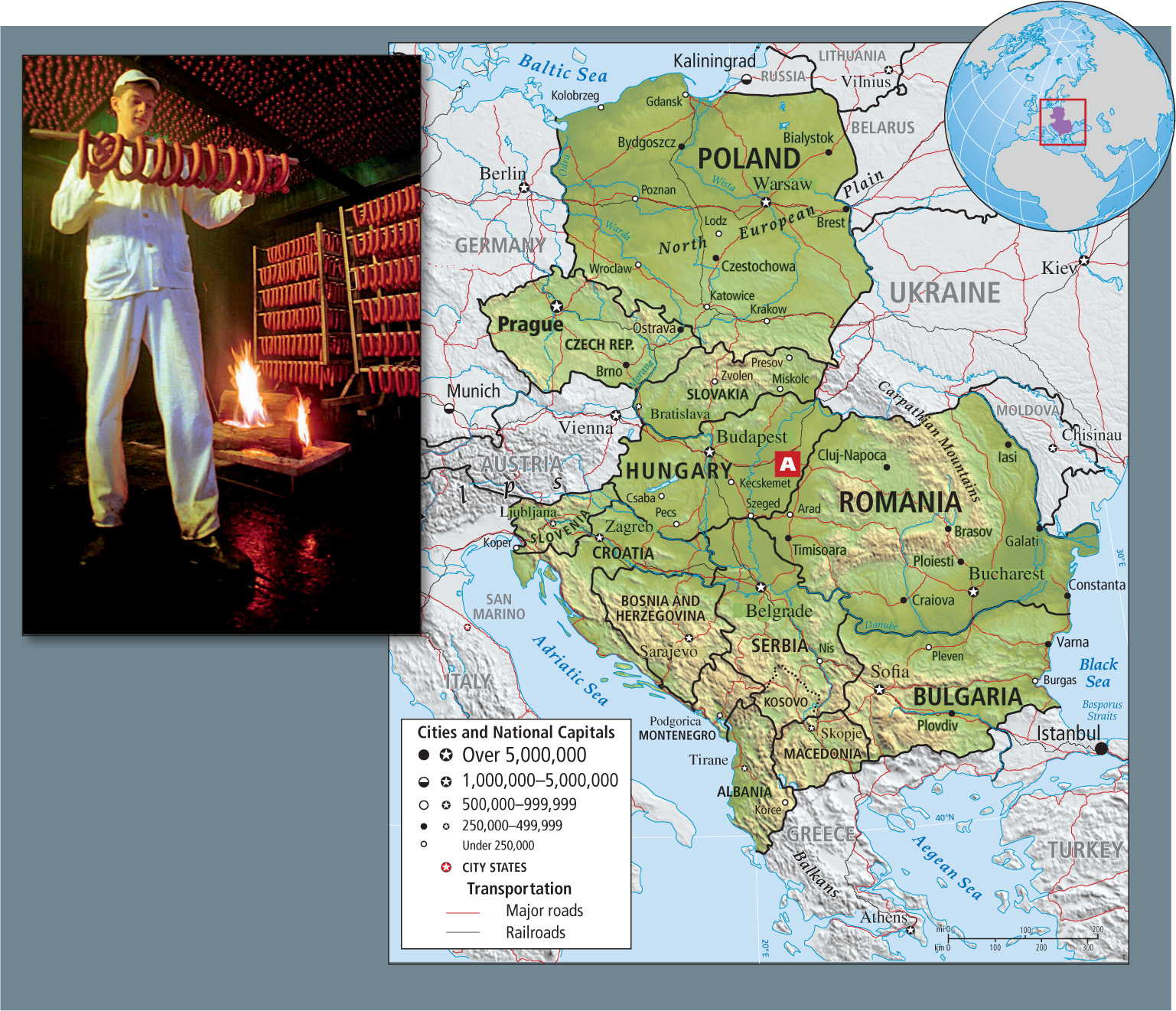

No part of Europe is in a more profound period of change than Central Europe (Figure 4.36 map and photo A). In the euphoria at the end of the Cold War (1989), many people believed that democracy and market forces would quickly turn around the region’s formerly Communist, centrally planned economies, which were sluggish and highly polluting. Instead, some parts of the region have had violent political turmoil, and virtually all have had at least temporary drops in their standard of living.

Transitions in Agriculture, Industry, and Society

Two tiers of Central European countries appear to be emerging. In the 1990s, those countries physically closest to western Europe—Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Slovenia—elected new democratic governments, made rapid progress toward market economies, and began to attract foreign investment. Access to consumer goods improved markedly. In 2004, all of these countries joined the European Union, and Croatia joined in 2013. Although conforming to the wide range of economic, environmental, and social requirements set forth by the European Union has not been easy, for many the challenge has been invigorating.

The countries with the greatest economic and social difficulties are Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania, and the countries that were in the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia—including the region of Kosovo). Romania and Bulgaria joined in 2007. For these countries, adjusting to democracy and privatization has proved difficult. Plagued by corruption and economic chaos, many governments have relaxed the pace of reforms as they struggle merely to maintain civil peace. In the 1990s, all of the former Yugoslavia, except Slovenia, became mired in a series of genocidal ethnic conflicts that belatedly resulted in European (including NATO) and U.S. military intervention.

After all this turmoil, not surprisingly, many people in all 13 countries are looking back nostalgically to the Communist era, when there was a strong authoritarian government, jobs were stable, and health care and education were free. Still, many observers are optimistic about even these poorest and most politically unstable parts of Central Europe. The countries in this region have useful natural resources for both agriculture and industry, and all have large, skilled yet inexpensive workforces that, until the recession began in 2008, were beginning to attract foreign investment. The countries’ most important trading partners are Germany, France, the Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom, Russia, and the United States, but the combination changes from country to country (Serbia has only limited trade). Until the financial instability of the EU crisis commencing in 2008, venture capitalists from Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, and even Croatia were beginning to invest in their neighbors to the south; and this investment is likely to eventually be revived.

In the Czech Republic in the 1990s, land that had been expropriated after World War II and turned into state farms and cooperatives was either reorganized into private owner-operated cooperatives or restored to its original owners and their descendants. By this time, though, the latter group had mostly become city dwellers, and rather than farming the land themselves, usually leased their regained land, either in small parcels to those who wished to become family farmers or in large parcels to the new private cooperatives. Eventually, 1.25 million acres (500,000 hectares), representing 30 percent of the country’s agricultural land, went to individual private farmers, large and small.

The EU economic advisers who readied the Czech Republic for entry into the European Union preferred larger, commercial farms because overproduction, which could contribute to falling commodity prices across Europe, is easier to control on large, corporately managed farms. EU advisers have suggested that the smaller family farms, which tend to be owned by independentminded individuals, find more lucrative uses for their land, such as farm tourism. They say that “dude farms”—similar to dude ranches in the western United States—or living history demonstrations of traditional food cultivation and preparation techniques could attract affluent urban families from all over Europe.

VIGNETTE

In Slovenia, Marinko Rodica proudly polishes the fine wood table in his small, elegant tasting cellar near the village of Truške, 1000 feet (300 meters) above the Adriatic Sea, near the giant port of Koper. He offers up seven different wines (one a blend) made from the six grapes he grows: three red—refošk, merlot, and cabernet sauvignon—and three white varieties—muškat, malvazija, and sivi pinot (pinot gris). Marinko recently won gold medals for his 2005 Truške Rdečce and 2007 Muškat at international fairs.

The climate and the location are ideal for growing grapes, and people have been making wine in this part of the Adriatic for about 2400 years. Over the last decade, Marinko turned his entire farm into an organic vineyard, with the aim of marketing his wine in the local tourist economy and eventually marketing it internationally.

Membership in the European Union has brought both benefits and challenges to wine producers (Figure 4.37). Their wines now have a wider market—Central Europe, Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan, and the United States—but vintners must adhere to strict EU agricultural policies. For example, Europeans are actually producing too much wine, lowering wine prices for all producers. The European Union wants to reduce the total vineyard acreage across Europe by some 400,000 hectares. Fortunately for Marinko, Slovenia, as one of the tiniest EU members, will not be grossly affected by this reduction. It could even increase demand for Marinko’s wine. Currently, over 90 percent of the 100 million liters of wine produced annually in Slovenia is consumed in Slovenia; plans are to increase wine exports over the next several years.

Marinko is ebullient. He has just entered into an association with the University of Primorska in Koper to teach viticulture and has donated some acreage and vines for university students to use to learn the craft. [Source: From field notes and research by Mac Goodwin and Simon Kerma, 2008, 2012.]aa

Industrial production was a specialty of Central Europe when these countries were part either of the Soviet bloc or Yugoslavia. So it would seem that manufacturing would be the best hope for competing in the EU marketplace. Unfortunately, much of Central Europe’s considerable industrial base is still burdened by legacies from the Communist era; it is polluting and energy intensive, with an emphasis on coal and steel production rather than on consumer goods that could replace imports.

Although industry in this subregion of Europe is still not particularly successful, industrial and product design is improving in places like Slovenia; regional trade shows are full of attractive, if still mostly only locally produced, goods. High-end artisanal products—such as handmade designer shoes, crystal glassware, luxury baby clothes, super-modern kitchens, attractive and meticulously constructed prefabricated houses, and beautiful, handmade church pipe organs—appear to be finding international markets.

Corruption has inhibited post-Communist industrial reform. In 2009, both Romania and Bulgaria narrowly avoided censure by the European Union for failing to rein in corruption. In some countries, the involvement of organized crime has plagued the sale of formerly state-owned industries, especially in military sectors. It has been difficult to develop financial regulations and freedom of the press, among other EU requirements, because of the amount of suspicion and wariness on the part of some political leaders. However, because the countries in the region want to remain in the good graces of the European Union, most have been working recently to control risky banking practices, to limit unscrupulous deals, and to reduce organized crime.

Progress in Market Reform

The governments of Central Europe are taking “free market–friendly” steps to help their economies grow more quickly. One strategy is to encourage foreign investment. Virtually all of the countries of Central Europe actively try to recruit foreign investors but often they then become discouraged by endless paperwork. Although there have been a number of false starts by investors unaware of the difficulties they would face, especially with poorly regulated banks, some firms are beginning to have some success. For example, the Smithfield firm in Romania, a major beneficiary of European Union CAP subsidies, has grown so rapidly that it has upset local economies (see the opening vignette).

New Experiences with Democracy

The advent of democracy in Central Europe has reduced some of the tensions associated with the economic transition because people have been able to vote against governments whose reforms created high levels of unemployment and inflation. Most countries have now had several rounds of parliamentary and local elections, and voters are becoming accustomed to Western-style political campaigns. However, the voters’ tendency to remove reformers before they can accomplish anything significant has dampened the enthusiasm of potential foreign investors, who are waiting for real and sustained change before they offer their money. The financial crisis in the European Union has brought pressure from voters and experts for revisions that will make the social safety net less costly and more efficient. For example, there are plans for new national pension systems to replace defunct communist pension plans. Viable pension systems are important on several counts: they will preserve financial stability for those who labored under communism and lost their safety net, they will keep active workers productive longer by pushing the retirement age from 58 to 65, and they will relieve younger workers from the burden of supporting impoverished aged parents.

Southeastern Europe: A Time of TroublesShortly after the exhilaration of the breakup of the Soviet Union, the socialist country of Yugoslavia and much of the rest of southeastern Europe went through a rather unexpected but brutal war. This region between Austria and Greece, formerly known as the Balkans, is home to many ethnic groups of differing religious faiths (Figure 4.38). Too often the assumption has been that it was this diversity that led to the conflict; but over the generations, the various ethnic groups managed to live together peacefully by intermarrying, blending, and realigning into new groups. However, local ethnic tensions erupted based on how groups sided with or against the Nazis during World War II.

Marshal Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s founder and leader until his death in 1980, recognizing the ethnic complexity of the countries he was governing, tried through the power of his personality to foster pan-Yugoslav nationalism. There was ethnic peace during Tito’s rule, but no national dialogue about the benefits of ethnic diversity. When Tito died, Serbs—the most populous ethnic group in the military and the federal government bureaucracy—tried to assert control. In response to the deteriorating economy and burgeoning Serbian nationalism, Slovenia and Croatia, Yugoslavia’s northernmost and wealthiest provinces, voted to declare independence in late 1990. Slovenes and Croats themselves became more nationalistic, and a spiral into competing nationalisms threatened.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Development of Market Economies

Tourism is increasingly recognized as an important part of a well-rounded market-based economy. The Adriatic has long attracted tourists from western Europe who are looking for an inexpensive sunny vacation. Medieval castles and wine festivals draw weekend visitors to rural areas. The cities of Central Europe, some of Europe’s oldest and most distinguished municipalities, are becoming magnets for tourists from America, Asia, and western Europe. One example is Budapest, the capital of Hungary (see Figure 4.1E). Situated on the Danube River and built on the remnants of the third-century Roman city of Aquincum, Budapest was one of the seats of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which ruled central Europe until World War I. By 2000, Budapest had reemerged as one of Europe’s finest metropolitan centers, filled with architectural treasures, museums, concert halls, art galleries, boutiques, discos, cabarets, theaters, and several universities of distinction.

Given the scale of the interethnic violence that occurred in the following years, it is not surprising that many people, especially outsiders, viewed ethnic hatred as the overriding cause of the conflict. However, more likely causes include an overall lack of ethical leadership, including the lack of guidance by Marshal Tito on multicultural affairs, invented myths about ethnically pure nation-states, and Serbian geopolitics.

In June of 1991, the Serb-dominated government and military of Yugoslavia allowed the province of Slovenia to separate after just a short skirmish—in part because of its location close to the heart of Europe and far from Serbia and in part because there were no significant supportive enclaves of ethnic Serbs in Slovenia. The Yugoslav government feared that unless it made a strong show of force in dealing with the Croats and the Bosnians, the rest of the non-Serb populations of Yugoslavia would also move to secede and take with them valuable territory, resources, and skilled people. This fear became a reality when Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina attempted to secede from Yugoslavia. The Serbs reacted brutally. While suffering ethnic cleansing, Croats and Bosnians retaliated with brutality and ethnic cleansing themselves, as did Albanians (also known as Kosovars).

Conflict sprang up again in the late 1990s in the province of Kosovo, the southern area of Serbia, dominated by ethnic Albanians. In the late 1980s, in order to divert public attention away from the country’s economic deterioration, Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, a Serb, aggressively claimed that Serbs were being threatened by Kosovar Albanians. In response, the guerrilla Kosovo Liberation Army was formed, supported by expatriates of Albanian ethnicity.

The various conflicts in and around Serbia devastated the economies of southeastern Europe. Dozens of bridges were bombed; the Danube River, a major transport conduit through Europe to the Black Sea, was blocked with wreckage. In 2000, an election in Serbia resoundingly removed Slobodan Milosevic from power, and in 2002 he was brought to trial for war crimes in the International Court of Justice (World Court) in The Hague (where he died of natural causes in 2006). To forestall any future troubles, the European Union and the countries of southeastern Europe had earlier agreed that, once Milosevic was gone, they would enact the Balkan Stability Pact. Funded by the European Union, this pact is promoting the recovery of the region through public and private investment as well as through social training to enhance the public acceptance of multicultural societies and the strengthening of informal democratic institutions. In May 2006, the people of Montenegro voted to declare independence from Serbia; in 2008 Kosovo declared independence, but its status remains in contention.

98. ATTACK ON U.S. EMBASSY IN BELGRADE DEMONSTRATES KOSOVO’S FLASHPOINT POTENTIAL

98. ATTACK ON U.S. EMBASSY IN BELGRADE DEMONSTRATES KOSOVO’S FLASHPOINT POTENTIAL

99. U.S. RECOGNIZES KOSOVO, REAFFIRMS FRIENDSHIP WITH SERBIA

99. U.S. RECOGNIZES KOSOVO, REAFFIRMS FRIENDSHIP WITH SERBIA

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The advent of democracy in Central Europe has reduced some of the tensions associated with the economic transition to capitalist market systems because people have been able to vote against governments whose reforms created high levels of unemployment and inflation.

The advent of democracy in Central Europe has reduced some of the tensions associated with the economic transition to capitalist market systems because people have been able to vote against governments whose reforms created high levels of unemployment and inflation. The states (with the exception of Slovenia) formerly known as the “Balkans,” underwent a long, tragic, interethnic (and partially religious) conflict resulting from the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. These states, most now reorganized as countries, are attempting to recover and meet EU membership requirements, which Croatia did in July 2013.

The states (with the exception of Slovenia) formerly known as the “Balkans,” underwent a long, tragic, interethnic (and partially religious) conflict resulting from the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. These states, most now reorganized as countries, are attempting to recover and meet EU membership requirements, which Croatia did in July 2013.