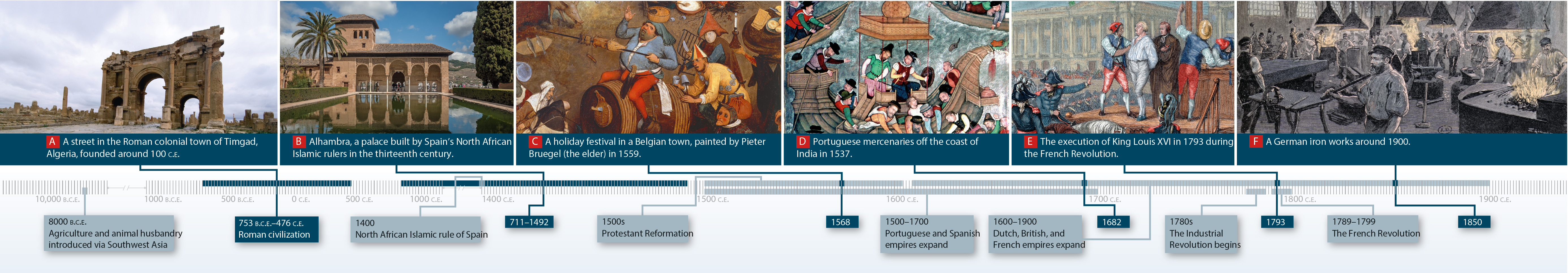

Human Patterns over Time

Over the last 500 years, Europe has profoundly influenced how the world trades, fights, thinks, and governs itself. The range of attempts to explain this influence varies widely. One argument is that Europeans are somehow a superior “breed” of humans. Another is that Europe’s many bays, peninsulas, and navigable rivers have promoted commerce to a greater extent there than elsewhere. But, in fact, much of Europe’s success is based on technologies and ideas it borrowed from elsewhere. For example, the concept of the peace treaty, so vital to current European and global stability, was first documented not in Europe but in ancient Egypt. In order to try to understand how Europe gained the leading role around the globe that it continues to have to this day, it is helpful to look at the broad history of this area.

Sources of European Culture

Starting about 10,000 years ago, the practice of agriculture and animal husbandry gradually spread into Europe from the uplands and plains associated with the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Southwest Asia and from farther east in Central Asia and beyond. Mining, metalworking, and mathematics also came to Europe from these places and from various parts of Africa. All of these borrowed innovations increased the possibilities for trade and economic development in Europe.

The first European civilizations were ancient Greece (800 to 86 b.c.e.) and Rome (753 b.c.e. to 476 c.e.). Located in southern Europe, both Greece and Rome initially interacted more with the Mediterranean rim, Southwest Asia, and North Africa than with the rest of Europe, which then had only a small and relatively poor, rural population. Later European traditions of science, art, and literature were heavily based on Greek ideas, which were themselves derived from yet earlier Egyptian and Southwest Asian (Arab and Persian) sources.

The Romans, after first borrowing heavily from Greek culture, also left important legacies in Europe. Many Europeans today speak Romance languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, and Romanian, all of which are largely derived from Latin, the language of the Roman Empire. European laws that determine how individuals own, buy, and sell land originated in Rome. Europeans then spread these legal customs throughout the world.

The practices that Romans used when colonizing new lands also shaped much of Europe. After a military conquest, the Romans secured control in rural areas by establishing large, plantation-like farms. Politics and trade were centered on new Roman towns built on a grid pattern that facilitated both commercial activity and the military repression of rebellions, as can be seen in Figure 4.9A. These same systems for taking and holding territory were later used when Europeans colonized the Americas, Asia, and Africa.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of Europe, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What about the photo of the ruins of Timgad reflects a particular Roman strategy for organizing space?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What about the architecture of Alhambra suggests technological sophistication and an astute understanding of climate?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What about this picture suggests relative prosperity in sixteenth-century Belgium?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What about this picture suggests how the Portuguese felt about the value of trade with India?

A. B. C. D.

Question

How is the execution of Louis XIV related to the evolution of democracy in Europe?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What does this photo indicate about the impact of the Industrial Revolution on employment in Europe?

A. B. C. D.

The influence of Islamic civilization on Europe is often overlooked. After the fall of Rome, while Europe was in a time known as the early medieval period (roughly 450 to 1300 c.e.; sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages), pre-Muslim (Arab and Persian) and then Muslim scholars preserved learning from Rome and Greece in large libraries, such as that in Alexandria, Egypt. Muslim Arabs originally from North Africa ruled Spain from 711 to 1492 (see Figure 4.9B). From the 1400s through the early 1900s, the Ottoman Empire (based in what is now Turkey) dominated much of southern Central Europe and Greece. The Arabs, Persians, and Turks all brought new technologies, food crops, architectural principles, and textiles to Europe from Arabia, Persia, Anatolia, China, India, and Africa. Arabs also brought Europe its numbering system, mathematics, and significant advances in medicine and engineering, building on ideas they picked up in South Asia.

Beginning 500 years ago, Europe began also to draw on a host of cultural features from the various colonies that were established in the Americas, Asia, and Africa. For example, many food crops now popular in Europe came mostly from the Americas (potatoes, corn, peppers, tomatoes, beans, and squash; see Table 3.1) and Southwest and Central Asia (wheat, leafy greens, garlic, onions, and apples).

The Inequalities of Feudalism

As the Roman Empire declined, a social system known as feudalism evolved during the medieval period (450–1500 c.e.). This system originated from the need to defend rural areas against local bandits and raiders from Scandinavia and the Eurasian interior. The objective of feudalism was to have a sufficient number of heavily armed, professional fighting men, or knights, to defend a much larger group of serfs, who were legally bound to live on and cultivate plots of land for the knights. Over time, some of these knights became a wealthy class of warrior-aristocrats, called the nobility, who controlled certain territories. Some nobles gained power over other nobles, amassing vast kingdoms.

The often-lavish lifestyles and elaborate castles of the wealthier nobility were supported by the labors of the serfs (Figure 4.10). Most serfs lived in poverty outside castle walls and, much like slaves, were legally barred from leaving the lands they cultivated for their protectors.

The Role of Urbanization in the Transformation of Europe

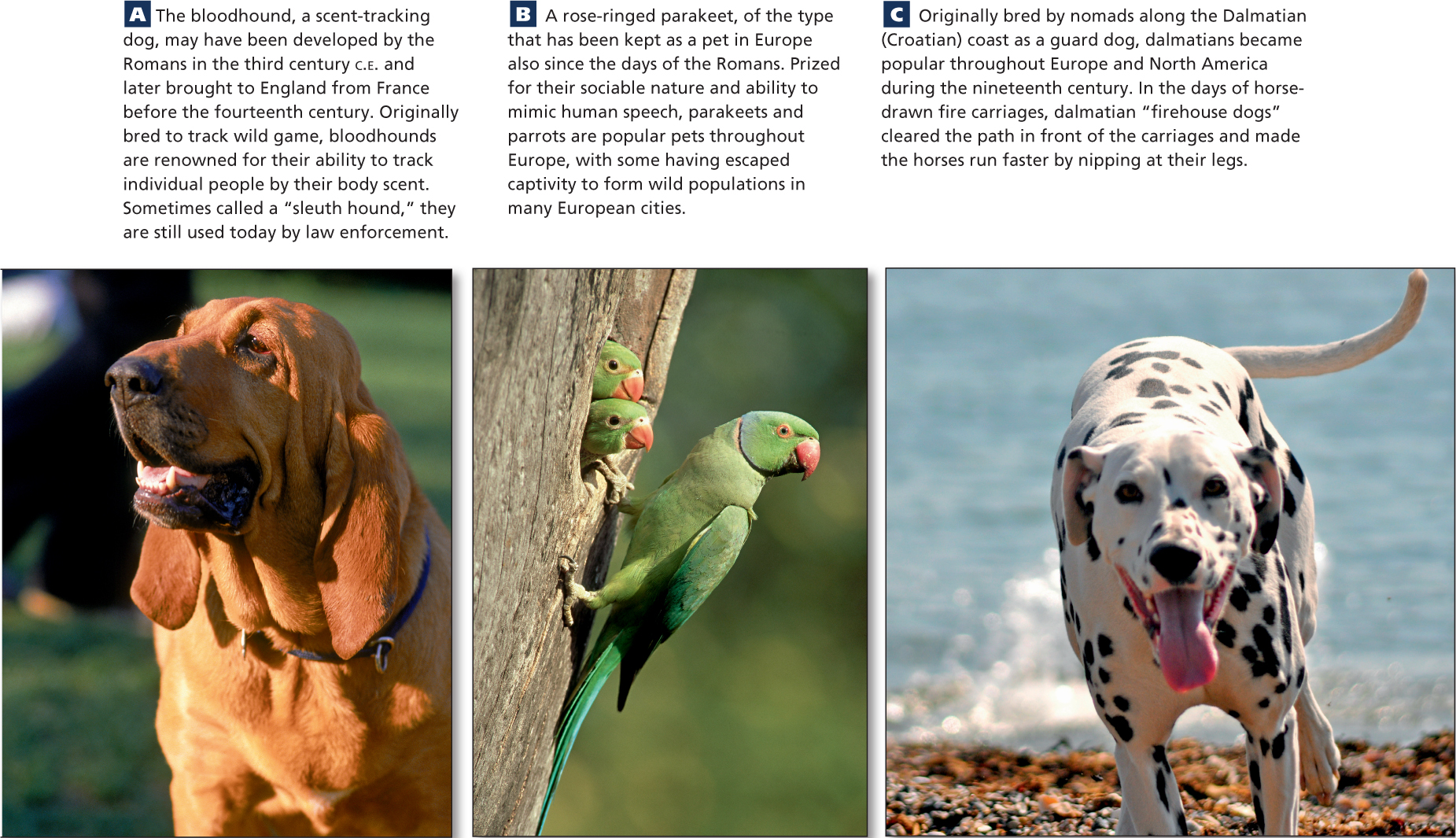

While rural life followed established feudal patterns, new political and economic institutions were developing in Europe’s towns and cities. Here, thick walls provided defense against raiders, and commerce and crafts supplied livelihoods, allowing the people to be more independent from feudal knights and kings. And Europeans, like people in other world regions, continued to develop distinctive cultures, including preferred pets (see Figure 4.11).

Located along trade routes, people in Europe’s urban areas were exposed to new ideas, technologies, and institutions from Southwest Asia, India, and China. Some of these innovations, such as banks, insurance companies, and corporations, provided the foundations for Europe’s modern economy. Over time, citizens of Europe’s urban areas established a pace of social and technological change that left the feudal rural areas far behind.

humanism a philosophy and value system that emphasizes the dignity and worth of the individual, regardless of wealth or social status

Urban Europe flourished in part because of laws that granted basic rights to urban residents. With adequate knowledge of these laws, set forth in legal documents called town charters, people with few resources could protect their rights even if challenged by those who were more wealthy and powerful. Town charters provided a basis for European notions of civil rights, which have proved hugely influential throughout the world. With strong protections for their civil rights, some of Europe’s townsfolk grew into a small middle class whose prosperity moderated the feudal system’s extreme divisions of status and wealth (see Figure 4.9C). A related outgrowth of urban Europe was a philosophy known as humanism, which emphasizes the dignity and worth of the individual, regardless of wealth or social status.

The liberating influences of European urban life transformed the practice of religion. Since late Roman times, the Catholic Church had dominated not just religion but also politics and daily life throughout much of Europe. In the 1500s, however, a movement known as the Protestant Reformation arose in the urban centers of the North European Plain. Reformers, among them Martin Luther, challenged Catholic practices—such as holding church services in Latin, which only a tiny educated minority understood—that stifled public participation in religious discussions. Protestants also promoted individual responsibility and more open public debate of social issues, altering the perception of the relationship between the individual and society. These ideas spread faster with the invention of the European version of the printing press (1450 c.e.), which enabled widespread literacy.

European Colonialism: The Founding and Acceleration of Globalization

Geographic Insight 3

Globalization and Development: As European powers like Spain, Portugal, England, and the Netherlands conquered vast overseas territories, they created trade relationships that transformed Europe economically and culturally and laid the foundation for the modern global economy. Today, Europe is struggling to remain globally competitive.

A direct outgrowth of the greater openness and connectivity of urban Europe was the exploration and subsequent colonization of much of the world by Europeans. The increased commerce and cultural exchange began a period of accelerated globalization that persists today (see the discussion in Chapter 1).

mercantilism a strategy for increasing a country’s power and wealth by acquiring colonies and managing all aspects of their production, transport, and trade for the colonizer’ benefit

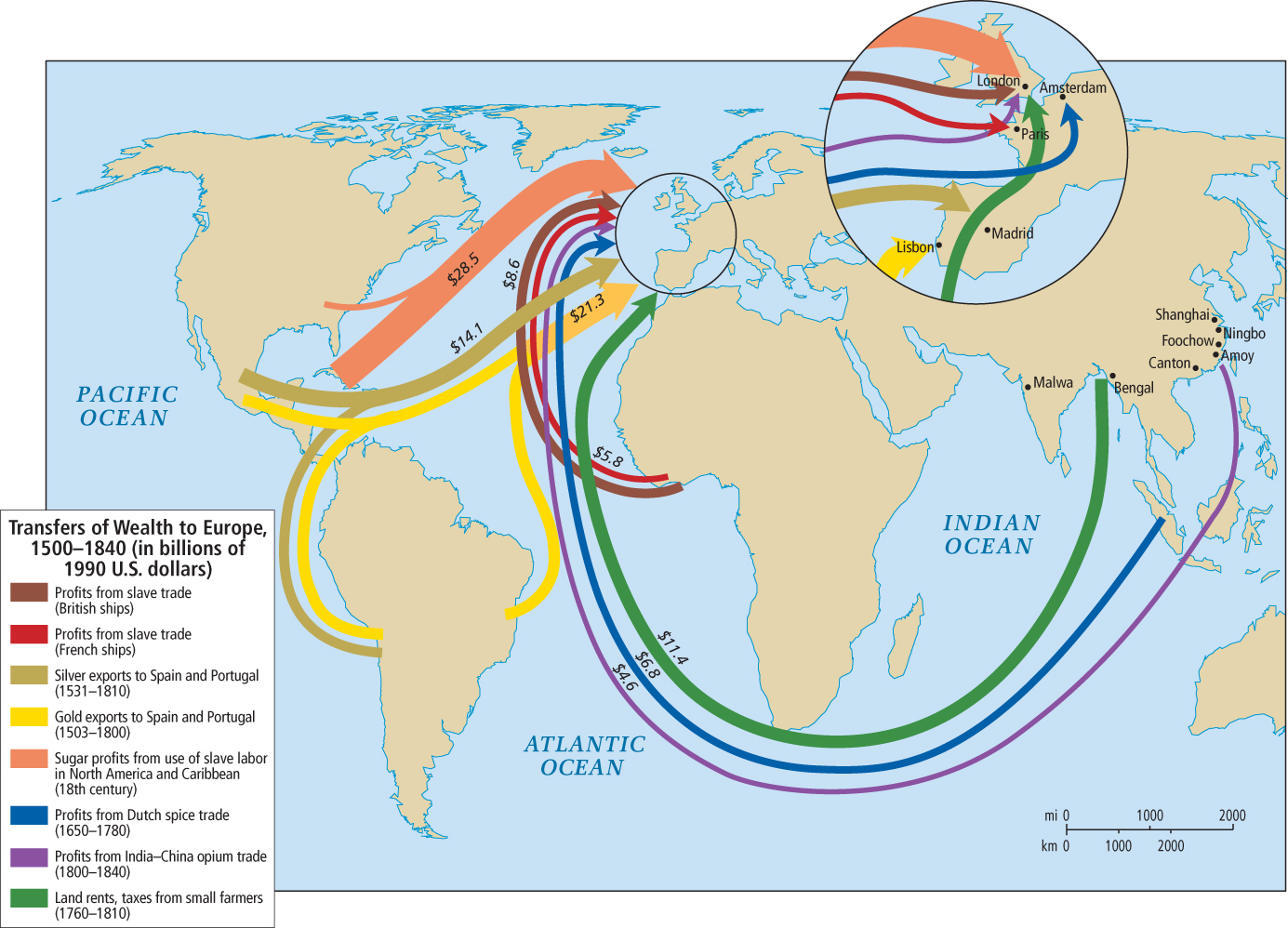

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Portugal took advantage of advances in navigation, shipbuilding, and commerce to set up a trading empire in Asia and a colony in Brazil (see Figure 4.9D). Spain soon followed, founding a vast and profitable empire in the Americas and the Philippines. By the seventeenth century, however, England, the Netherlands, and France had seized the initiative from Spain and Portugal. All European powers implemented mercantilism, a strategy for increasing a country’s power and wealth by acquiring colonies and managing all aspects of their production, transport, and trade for the colonizer’s benefit (Figure 4.12).

Mercantilism supported the Industrial Revolution in Europe (page 206) by supplying cheap resources from around the globe for Europe’s new factories. The colonies also became markets for European-manufactured goods.  88. ART EXHIBIT ENCOMPASSES THE WORLD OF PORTUGUESE EXPLORATIONS

88. ART EXHIBIT ENCOMPASSES THE WORLD OF PORTUGUESE EXPLORATIONS

By the mid-1700s, wealthy merchants in London, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin, and other western European cities were investing in new industries. Workers from rural areas poured into urban centers in England, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Germany to work in new manufacturing industries and mining. Wealth and raw materials flowed in from colonial ports in the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Some cities, such as Paris and London, were elaborately rebuilt in the 1800s to reflect their roles as centers of global empires.

By 1800, London and Paris, each of which had a million inhabitants, were Europe’s largest cities, a status that eventually brought them to their present standing as world cities (cities of worldwide economic or cultural influence). London is a global center of finance, and Paris is a cultural center that has influence over global consumption patterns, from food to fashion to tourism.

Also by the nineteenth century, the English, French, and Dutch (the people who live in the Netherlands, or Holland) overshadowed the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires and extended their influence into Asia and Africa. By the twentieth century, European colonial systems had strongly influenced nearly every part of the world.

The overseas empires of England, the Netherlands, and eventually France were the beginnings of the modern global economy. The riches they provided shifted wealth, investment, and general economic development away from southern Europe and the Mediterranean and toward western Europe.

Urban Revolutions in Industry and Democracy

Geographic Insight 4

Urbanization, Power, and Politics: Rates of urbanization and democratization in Europe are linked, but both rates vary across the region. Northern Europe is the most urbanized (close to 80 percent) and has the most democratic participation. Levels of both urbanization and democratization fall to the south and east.

The wealth derived from Europe’s colonialism helped fund two of the most dramatic transformations in a region already characterized by rebirth and innovation: the industrial and democratic revolutions. Both first took place in urban Europe.

The Industrial RevolutionEurope’s Industrial Revolution—particularly Britain’s ascendancy as the leading industrial power of the nineteenth century—was intimately connected with colonial expansion and sugar production. In the seventeenth century, Britain developed a small but growing trading empire in the Caribbean, North America, and South Asia, which provided it with access to a wide range of raw materials and to markets for British goods.

Sugar, produced by British colonies in the Caribbean, was an especially important trade crop (see Figure 4.12). Sugar production is a complex process that requires major investments in equipment, and for which a great deal of labor was once needed. Slaves were forcibly brought from Africa to help grow and process sugar. The skilled management and large-scale organization needed for sugar later provided a production model for the Industrial Revolution. The mass production of sugar also generated enormous wealth that helped fund industrialization.

By the late eighteenth century, Britain was introducing mechanization into its industries, first in textile weaving and then in the production of coal and steel. By the nineteenth century, Britain was the world’s greatest economic power, with a huge and growing empire, expanding industrial capabilities, and sporting the world’s most powerful navy. Its industrial technologies spread throughout continental Europe (see Figure 4.9F), North America, and elsewhere, thereby transforming millions of lives in the process.

Urbanization and Democratization

Industrialization led to massive growth in urban areas in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Extremely low living standards in Europe’s cities created tremendous pressures for change in the political order, ultimately leading to democratization. Most early industrial jobs were dangerous and unhealthy, demanding long hours and offering little pay. Poor people were packed into tiny, airless spaces that they shared with many others. Children were often weakened and ill because of poor nutrition, industrial pollution, inadequate sanitation and health care, and being used as laborers. Water was often contaminated, and most sewage ended up in the streets. Opportunities for advancement through education were restricted to a tiny, wealthy elite.

The ideas and information gained by the few key people who did learn to read gave some the incentive to organize and protest for change. After lengthy struggles, democracy was expanded to Europe’s huge and growing working class, and power, wealth, and opportunity were distributed more evenly throughout society. However, the road to democracy in Europe was rocky and violent, just as it is now in many parts of the world.

In 1789, the French Revolution led to the first major inclusion of common people in the political process in Europe. Angered by the extreme disparities of wealth in French society, and inspired by news of the popular revolution in North America, the poor rebelled against the monarchy and the elite-dominated power structure that still controlled Europe (see Figure 4.9E). As a result, the general populace, especially in urban areas, became involved in governing through democratically elected representatives. The democratic expansion created by the French Revolution ultimately proved short-lived as governments dominated by the elite soon regained control in France. Nevertheless, the French Revolution provided crucial inspiration to later urban democratic political movements in France and elsewhere.

The Impact of CommunismDuring the struggles that resulted ultimately in the expansion of democracy, popular discontent erupted periodically in the form of new revolutionary political movements that threatened the established civic order. The political philosopher and social revolutionary Karl Marx framed the mounting social unrest in Europe’s cities as a struggle between socioeconomic classes. His treatise The Communist Manifesto (1848) helped social reformers across Europe articulate ideas about how wealth could be more equitably distributed. East of Europe in Russia, Marx’s ideas inspired the creation of a revolutionary communist state in 1917, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, often referred to as the USSR or the Soviet Union. Eventually, the Soviet Union extended its ideology and state power throughout Central Europe.

In West, North, and South Europe, communism gained some popularity, but this tended to lead to the formation of Communist political parties that operated peacefully within the context of democratizing political systems. In countries like France, Italy, and Spain, Communist political parties are still influential and often form governing coalitions with other parties.

Popular Democracy and NationalismThroughout Europe, innumerable struggles between urban working-class people and the authorities continued during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, yielding two main results: workers throughout Europe gained the right to form unions that could bargain with employers and the government for higher wages and better working conditions; and there was an increase in democratization as most national governments eventually began to derive their authority from competitive elections in which all adult citizens could vote.

nationalism devotion to the interests or culture of a particular country, nation, or cultural group; the idea that a group of people living in a specific territory and sharing cultural traits should be united in a single country to which they are loyal and obedient

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the development of democracy was also linked to the idea of nationalism, or allegiance to the state. The notion spread that all the people who lived in a certain area formed a nation, and that loyalty to that nation should supersede loyalties to family, clan, or individual monarchs. Eventually, the whole map of Europe was reconfigured, and the mosaic of kingdoms gave way to a collection of nation-states. All of these new nations were, at varying paces, transformed into democracies by the political movements arising in Europe’s industrial cities. Nationalism was a major component of both World War I and II, so in the period after the wars—called the post-war era—and as the European Union was constructed, supernationalism was recognized as a problem and deemphasized.

Democracy and the Welfare State

welfare state a government that accepts responsibility for the well-being of its people, guaranteeing basic necessities such as education, affordable food, employment, and health care for all citizens

Channeled through the democratic process, public pressure for improved living standards moved most European governments toward becoming welfare states by the mid-twentieth century. Such governments accept responsibility for the well-being of their people, guaranteeing basic necessities such as education, employment, affordable food, and health care for all citizens. In time, government regulations on wages, hours, safety, and vacations established more harmonious relations between workers and employers. The gap between rich and poor declined, and overall civic peace increased. And although welfare states were funded primarily through taxes, industrial productivity and overall economic activity did not decline, but rather increased, as did general prosperity.

Modern Europe’s welfare states have yielded generally adequate to high levels of well-being for all citizens. However, just how much support the welfare state should provide is still a subject of hot debate—one that is currently being addressed in different ways across Europe (see page 225).

Two World Wars and Their Aftermath

Despite Europe’s many advances in industry and politics, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the region still lacked a system of collective security that could prevent war among its rival nations. Between 1914 and 1945, two horribly destructive world wars left Europe in ruins, no longer the dominant region of the world. At least 20 million people died in World War I (1914–1918) and 70 million in World War II (1939–1945). During World War II, Germany’s Nazi government killed 15 million civilians during its failed attempt to conquer the Soviet Union. Eleven million civilians died at the hands of the Nazis during the Holocaust, a massive execution of 6 million Jews and 5 million gentiles (non-Jews), including ethnic Poles and other Slavs, Roma (Gypsies), disabled and mentally ill people, gays, lesbians, transgendered people, and political dissidents.  89. THE WORLD REMEMBERS VICTIMS OF HOLOCAUST

89. THE WORLD REMEMBERS VICTIMS OF HOLOCAUST

Holocaust during World War II, a massive execution by the Nazis of 6 million Jews and 5 million gentiles (non-Jews), including ethnic Poles and other Slavs, Roma (Gypsies), disabled and mentally ill people, gays, lesbians, transgendered people, and political dissidents

Roma the now-preferred term in Europe for Gypsies

Iron Curtain a long, fortified border zone that separated western Europe from (then) eastern Europe during the Cold War

Cold War a period of conflict, tension, and competition between the United States and the Soviet Union that lasted from 1945 to 1991

capitalism an economic system characterized by privately owned businesses and industrial firms that adjust prices and output to match the demands of the market

communism an ideology and economic system, based largely on the writings of the German revolutionary Karl Marx, in which, on behalf of the people, the state owns all farms, industry, land, and buildings (a version of socialism)

central planning a communist economic model in which a central bureaucracy dictates prices and output, with the stated aim of allocating goods equitably across society according to need

During World War II, Russia joined the Allies (Great Britain and the British Commonwealth; France, except during the German occupation of 1940–1944; Poland; the United States; Belgium; Brazil; Czechoslovakia; Ethiopia; Greece; India; Mexico; the Netherlands; Norway; and Yugoslavia) in defeating Germany, the country seen as the instigator of both world wars. After World War II ended in 1945, finding a lasting peace became a primary goal that eventually led to the formation of the European Union. But first, a number of enduring changes took place. Germany was divided into two parts. West Germany became an independent democracy allied with the rest of western Europe—especially Britain and France—and the United States. Since Russia controlled East Germany and the rest of Central Europe (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Moldova, and Belarus) after the war, under Russia’s dominant leadership these war-devastated countries solidified into an ideologically Communist, or Soviet, bloc. The line between East and West Germany was part of what was called the Iron Curtain, a long, fortified border zone that separated western Europe from Central Europe. Yugoslavia did not become part of the Soviet bloc but also kept itself insulated from the West, partly to protect its socialized economy.

The Cold WarThe division of Europe created a period of conflict, tension, and competition between the United States and the Soviet Union known as the Cold War, which lasted from 1945 to 1991. During this time, once-dominant Europe, and indeed the entire world, became a stage on which the United States and the Soviet Union competed for dominance. The central issue was the competition between capitalism—characterized by privately owned businesses and industrial firms that adjusted prices and output to match the demands of the market—and communism (actually a version of socialism), in which the state owned all farms, industry, land, and buildings. After 1945, in most of what we now call Central Europe, the Soviet Union forcibly implemented a communist-inspired economic model known as central planning, in which a central bureaucracy dictated prices and output, with the stated aim of allocating goods and services equitably across society according to need. This system was successful in alleviating long-standing poverty and illiteracy among the working classes and for women, but it was rife with waste, corruption, and bureaucratic bungling. It ultimately collapsed in the 1990s due to inefficiency, insolvency, high levels of environmental pollution, and public demands for more democratic participation.

The rest of post-war Europe, especially western Europe, successfully developed capitalist economies with financial support from the United States under the Marshall Plan and from the governments of the involved countries. Basic facilities, such as roads, housing, and schools, were rebuilt. Economic reconstruction proceeded rapidly in the decades after World War II and included special attention to the social welfare needs of the general public.  91. MARSHALL PLAN’S 61ST ANNIVERSARY

91. MARSHALL PLAN’S 61ST ANNIVERSARY

Decolonization, Power and Politics, and Conflict in Modern EuropeEurope’s decline during the two world wars also led to the loss of its colonial empires. Many European colonies had participated in the wars, with some (India, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, and Algeria) suffering extensive casualties, and almost all emerging economically devastated. After World War II, Europe was less able to assert control over its colonies as their demands for independence grew. By the 1960s, most former European colonies had gained independence, often after bloody wars fought against European powers and their local allies.

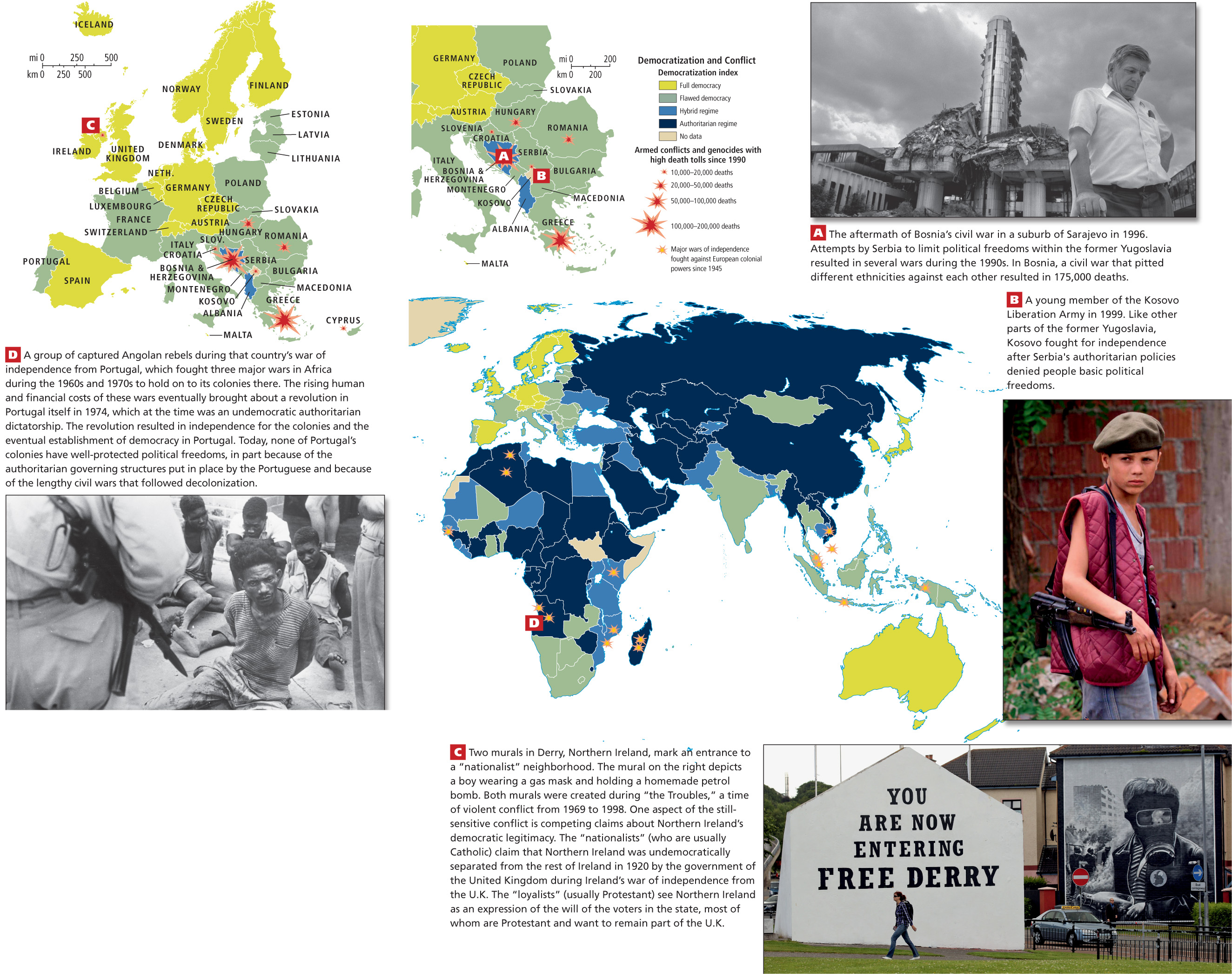

Democracy’s long history in Europe (if not in Europe’s colonies) entered a new era after World War II, when most of West, South, and North Europe reorganized more strongly around democratic principles and humanitarian ideals. This process was supported by the United States, though several authoritarian European regimes, such as that of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who ruled from 1936–1975, also received U.S. support. Portugal, also an authoritarian European country after the war, remained a dictatorship and colonial power in Africa until 1974 (Figure 4.13D). Elsewhere in Europe, political freedoms were compromised by violence, as in the case of Northern Ireland, which until the late 1990s had sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants so severe that free and fair democratic elections were not possible (see Figure 4.13C). Central Europe did not begin to democratize until the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991 as its former satellites, one by one, declared independence. Yugoslavia, a large communist republic in southern Central Europe, always firmly outside the Soviet bloc, also dissolved beginning in the early 1990s. There democratization was hampered by a powerful wave of ethnic xenophobia and violence (see Figure 4.13A, B).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in Europe, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What clues in the photo suggest war and not some other calamity?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What are the political implications of the sign announcing entry into Free Derry? What might be the reasons for showing a child wearing a gas mask?

A. B. C. D.

Question

Why could it be said that independence movements in Portugal’s African colonies brought democracy to Portugal?

A. B. C. D.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

During the medieval period, political and economic transformations in Europe’s towns and cities challenged the feudal system that dominated rural areas.

During the medieval period, political and economic transformations in Europe’s towns and cities challenged the feudal system that dominated rural areas. Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development The vast overseas colonies of various European states created trade relationships that persist in the modern global economy. Europe was transformed and continues to benefit.

Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development The vast overseas colonies of various European states created trade relationships that persist in the modern global economy. Europe was transformed and continues to benefit. Most of the countries in the world have been ruled by a European colonial power at some point in their history.

Most of the countries in the world have been ruled by a European colonial power at some point in their history. Geographic Insight 4Urbanization, Power, and Politics The growth of cities set the stage for increasing the political power of ordinary people, but democratization in Europe has proceeded at different rates across the region and was interrupted by two world wars.

Geographic Insight 4Urbanization, Power, and Politics The growth of cities set the stage for increasing the political power of ordinary people, but democratization in Europe has proceeded at different rates across the region and was interrupted by two world wars. The road to democracy in Europe was rocky and at times violent.

The road to democracy in Europe was rocky and at times violent.