Sociocultural Issues

The European Union was conceived primarily to promote economic cooperation and free trade, but its programs have social implications as well. As population patterns change across Europe, attitudes toward immigration, gender roles, and social welfare programs are also evolving. Christian religious factions and language rivalry, once divisive issues in the region, have now almost disappeared as a focus of disputes. Meanwhile, immigration, especially by people of the Muslim faith, is a source of apprehension, perhaps because these days few Europeans identify themselves as belonging to any religious faith and they are left uncomfortable by shows of religious fervor.

Population Patterns

Geographic Insight 6

Population and Gender: Europe’s population is aging, as working women are choosing to have only one or two children. Immigration by young workers is partially countering this trend.

Population patterns in Europe portended processes that are emerging around the world. Europe’s high population density and urbanization trends are long-standing. A newer but prominent phenomenon, the aging of the populace and lower birth rates affect all manner of European social policies.

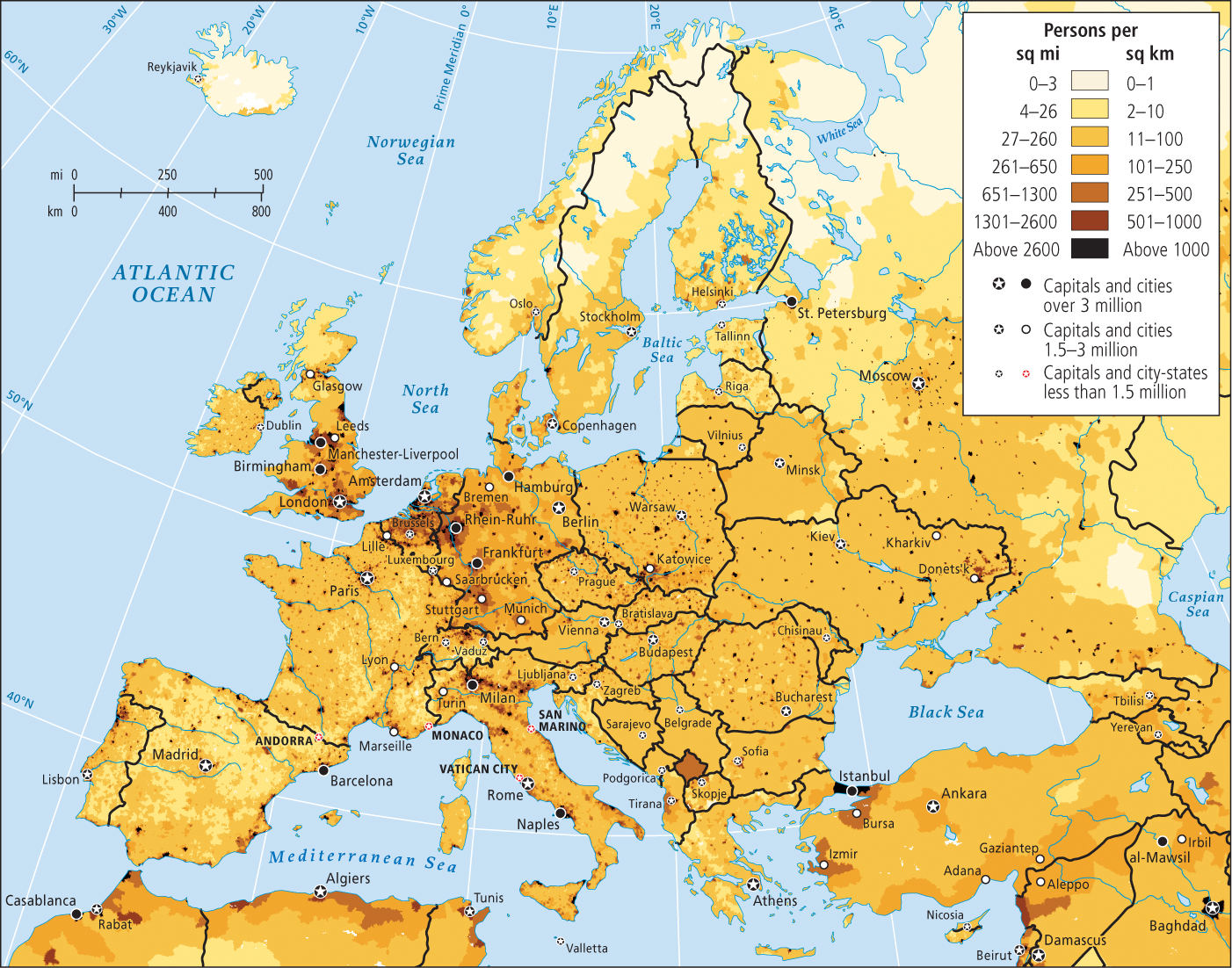

Population Distribution and UrbanizationThere are currently about 540 million Europeans. Of these, 500 million live within the European Union. The highest population densities stretch in a discontinuous band from the United Kingdom south and east through the Netherlands and central Germany into northern Switzerland (Figure 4.19). Northern Italy is another zone of high density, along with pockets in many countries along the Mediterranean coast. Overall, Europe is one of the more densely occupied regions on Earth, as shown on the world population density map in Figure 1.8.

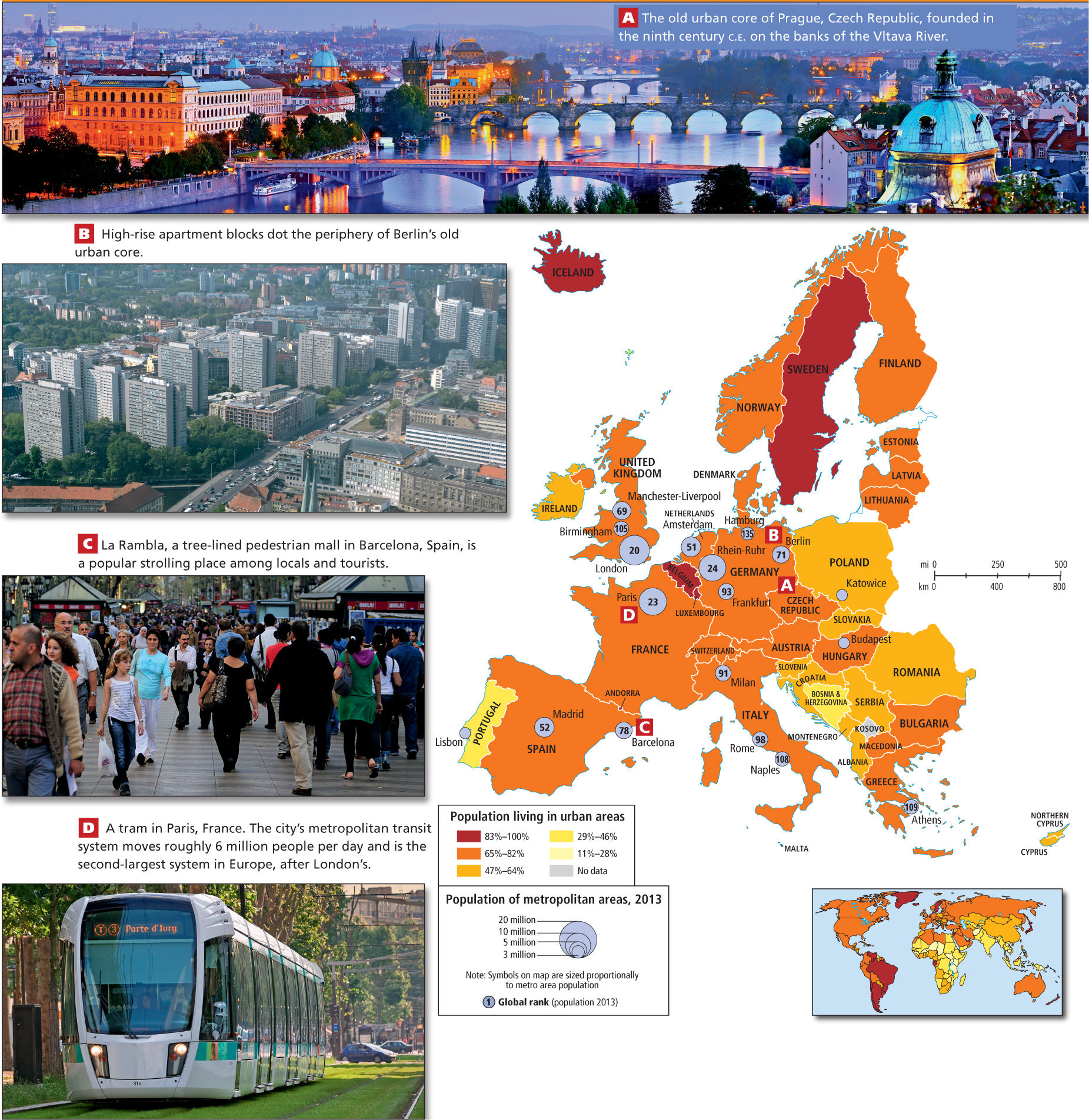

Europe is a region of cities surrounded by well-developed rural hinterlands where urban dwellers often go to enjoy leisure hours. These cities are the focus of the modern European economy, which, though long based on agriculture, trade, and manufacturing, is now primarily service oriented. In West and North Europe, more than 75 percent of the population lives in urban areas. In South and Central Europe, urbanization rates are slightly lower, but village residents often commute to urban jobs. As noted earlier, many European cities began as trading centers more than a thousand years ago and still bear the architectural marks of medieval life in their historic centers (Figure 4.20A). These old cities are located either on navigable rivers in the interior or along the coasts because water transportation figured prominently (as it still does) in Europe’s trading patterns.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in Europe, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What are the likely reasons why Prague is located along a river?

A. B. C. D.

Question

What can you see in this picture that illustrates what we know about urban life in Europe?

A. B. C. D.

Question

Describe the people you see walking in this picture. How might walking as a mode of transportation affect the environment and urban spaces of Barcelona?

A. B. C. D.

Question

How does the amount of greenhouse gas produced by rail-based public transportation compare to that of private automobile—based transportation?

A. B. C. D.

Since World War II, nearly all the cities in Europe have expanded around their perimeters in concentric circles of apartment blocks (see Figure 4.20B). Usually, well-developed rail and bus lines link the blocks to one another, to the old central city, and to the surrounding countryside. Land is scarce and expensive in Europe, so only a small percentage of Europeans live in single-family homes, although the number is growing. Even single-family homes tend to be attached or densely arranged on small lots. Except in public parks, which are common, one rarely sees the sweeping lawns familiar to many North Americans. Because publicly funded transportation is widely available, many people live without cars, in apartments near city centers (see Figure 4.20C, D). However, many others commute daily by car, bus, or train from suburbs or ancestral villages to work in nearby cities. Although deteriorating housing and slums do exist, substantial public spending (on sanitation, water, utilities, education, health care, housing, and public transportation) help most people maintain a generally high standard of urban living.

Europe’s Aging Population Linked to Gender IssuesEurope’s population is aging as families are choosing to have fewer children and life expectancies are increasing. Between 1960 and 2012, the proportion of those 14 years and under declined from 27 percent to 16 percent, while those over 65 increased from 9 percent to 16 percent. By comparison, young people comprised 26 percent of the global population in 2012, while older generations accounted for 8 percent. Life expectancies now range close to 80 years in North, West, and South Europe, and this is reflected in urban landscapes, where the elderly are more common than children. In East Europe, life expectancies are notably lower: 66 years for men, 76 years for women.

Overall, Europe is now close to a negative rate of natural increase (<0.0), the lowest in the world. Birth rates are low, are shrinking across Europe, and are lowest in the wealthiest country—Germany. Increasingly, the one-child family is common throughout Europe, except among immigrants from outside the region, who are the major source of population growth. However, once they have assimilated into European life, most immigrants, too, choose to have small families.

The declining birth rate is illustrated in the population pyramids of European countries (Figure 4.21), which look more like lumpy towers than pyramids. Examples are the population pyramid of Sweden and of the whole European Union (see Figure 4.21B, C). The pyramids’ narrowing base indicates that for the last 35 years, far fewer babies have been born than in the 1950s and 1960s, when there was a post-war baby boom across Europe. By 2000, 25 percent of adult Europeans were having no children at all.

The reasons for these trends are complex. For one thing, more and more women want professional careers. This alone could account for late marriages and lower birth rates; 25 percent of German women are choosing to remain unmarried well into their thirties. Historically, many governments have made few provisions for working mothers, beyond paid maternity leave. Germany, for example, is just beginning to address that there is insufficient day care available for children under age 3. Because German school days run from 7:30 a.m. to noon or 1:00 p.m., many German women choose not to become mothers because they would have to settle for part-time jobs in order to be home by 1:00 p.m. To encourage higher birth rates, there is a move within the European Union to give one parent (mother or father) a full year off with reduced pay after a child is born or adopted; to provide better preschool care; to lengthen school days; and to serve lunch at school (see the discussion of gender).

A stable population with a low birth rate has several consequences. Because fewer consumers are being born, economies may contract over time. Demand for new workers, especially highly skilled ones, may go unmet. Further, the number of younger people available to provide expensive and time-consuming health care for the elderly, either personally or through tax payments, will decline. Currently, for example, there are just two German workers for every retiree. Immigration provides one solution to the dwindling number of young people. However, Europeans are reluctant to absorb large numbers of immigrants, especially from distant parts of the world where cultural values are very different from those in Europe.

Immigration and Migration: Needs and Fears

Schengen Accord an agreement signed in the 1990s by the European Union and many of its neighbors that allows for free movement across common borders

Until the mid-1950s, the net flow of migrants was out of Europe, to the Americas, Australia, and elsewhere. By the 1990s, the net flow was into Europe. In the 1990s, most of the European Union (plus Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland) implemented the Schengen Accord, an agreement that allows free movement of people and goods across common borders. The accord has facilitated trade, employment, tourism, and most controversially, migration within the European Union. The Schengen Accord has also indirectly increased both the demand for immigrants from outside the European Union and their mobility once they are in the European Union (Figure 4.22).  92. AFTER 50 YEARS, EUROPE STILL COMING TOGETHER

92. AFTER 50 YEARS, EUROPE STILL COMING TOGETHER

Attitudes Toward Internal and International Migrants and CitizenshipLike citizens of the United States, Europeans have ambivalent attitudes toward migrants. The internal flow of migration is mostly from Central Europe into North, West, and South Europe. These Central European migrants are mostly treated fairly, although prejudices against the supposed backwardness of Central Europe are still evident. Immigrants from outside Europe, so-called international immigrants, meet with varying levels of acceptance.

guest workers legal workers from outside a country who help fulfill the need for temporary workers but who are expected to return home when they are no longer needed

International immigrants often come both legally and illegally from Europe’s former colonies and protectorates across the globe. Many Turks and North Africans come legally as guest workers who are expected to stay for only a few years, fulfilling Europe’s need for temporary workers in certain sectors. Other immigrants are refugees from the world’s trouble spots, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, and Sudan. Many also come illegally from all of these areas.

While some Europeans see international immigrants as important contributors to their economies—providing needed skills and labor and making up for the low birth rates—many oppose recent increases in immigration. Studies of public attitudes in Europe show that immigration is least tolerated in areas where incomes and education are low. Central and South Europe are the least tolerant of new immigrants, possibly because of fears that immigrants may drive down wages that are already relatively low. North and West Europe, with higher incomes and generally more stable economies, are the most tolerant. In response, the European Union is increasing its efforts to curb illegal immigration from outside Europe while encouraging EU citizens to be more tolerant of legal migrants.

A Case Study: The Rules for Assimilation: Muslims in Europe

assimilation the loss of old ways of life and the adoption of the lifestyle of another country

In Europe, culture plays as much of a role in defining differences between people as race and skin color. An immigrant from Asia or Africa may be accepted into the community if he or she has gone through a comprehensive change of lifestyle. Assimilation in Europe usually means giving up the home culture and adopting the ways of the new country. If minority groups—such as the Roma, who have been in Europe for more than a thousand years—maintain their traditional ways, it is nearly impossible for them to blend into mainstream society.  101. THE ART OF INTEGRATION IN GERMANY

101. THE ART OF INTEGRATION IN GERMANY

Europe’s small but growing Muslim immigrant population (Figure 4.23) is presently the focus of assimilation issues in the European Union. Muslims come from a wide range of places and cultural traditions, including North Africa, Turkey, and South Asia. Some of these immigrants maintain traditional dress, gender roles, and religious values, while others have assimilated into European culture. The deepening alienation that has boiled over in recent years among some Muslim immigrants and their children—resulting in protests, riots, and sometimes even terrorism—relates primarily to the systematic exclusion of these less-assimilated Muslims from meaningful employment, social services, and higher education. In the wake of protests by Muslim residents, investigations by the French media revealed that the protestors’ complaints were indeed legitimate. However, many Europeans, unaware of the extent to which their own societies discriminate and engage in Muslim stigmatizing, have come to view Muslim protesters as simple malcontents. Meanwhile, it is young Muslims born in Europe and schooled in the lofty ideals of the European Union, who have never known life in any other place, who harbor the greatest resentment against the constricted opportunities they face.aa

In some cases, conflicts have also arisen over European perceptions of cultural aspects of Islam, such as the hijab (one of several traditional coverings for women). For example, in France in 2004, wearing of the hijab by observant Muslim schoolgirls became the center of a national debate about civil liberties, religious freedom, and national identity. French authorities wanted to ban the hijab but were wary of charges of discrimination. Eventually the French declared all symbols of religious affiliation illegal in French schools (including crosses and yarmulkes, the Jewish head covering for men).

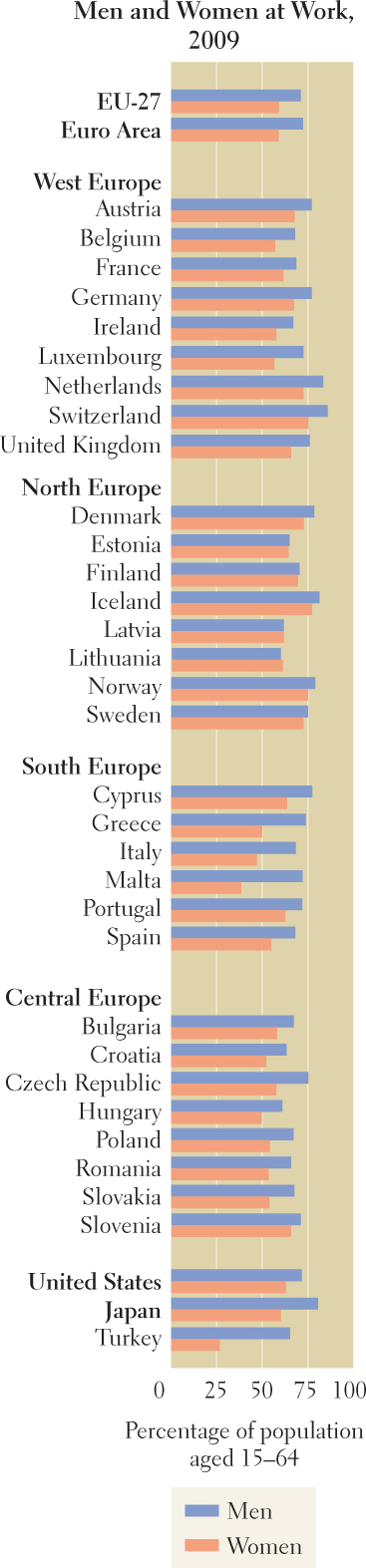

Changing Gender Roles

Gender roles in Europe have changed significantly from the days when most women married young and worked in the home or on the family farm. Increasing numbers of European women are working outside the home, and the percentage of women in professional and technical fields is growing rapidly (Figure 4.24). Nevertheless, European public opinion among both women and men largely holds that women are less able than men to perform the types of work typically done by men, and that men are less skilled at domestic, caregiving, and nurturing duties. In most places, men have greater social status, hold more managerial positions, earn on average about 15 percent more pay for doing the same work, and have greater autonomy in daily life than women—more freedom of movement, for example. These male advantages retain a stronger hold in Central and South Europe today than they do in West and North Europe.

double day the longer workday of women with jobs outside the home who also work as caretakers, housekeepers, and/or cooks for their families

Certainly, younger men now assume more domestic duties than did their fathers, but women who work outside the home usually still face what is called a double day in that they are expected to do most of the domestic work in the evening in addition to their job outside the home during the day. UN research shows that in most of Europe, women’s workdays, including time spent in housework and child care, are 3 to 5 hours longer than men’s. (Iceland and Sweden reported that women and men there share housework equally.) Women burdened by the double day generally operate with somewhat less efficiency in a paying job than do men. They also tend to choose employment that is closer to home and that offers more flexibility in the hours and skills required. These more flexible jobs (often erroneously classified as part-time) almost always offer lower pay and less opportunity for advancement, though not necessarily fewer working hours.

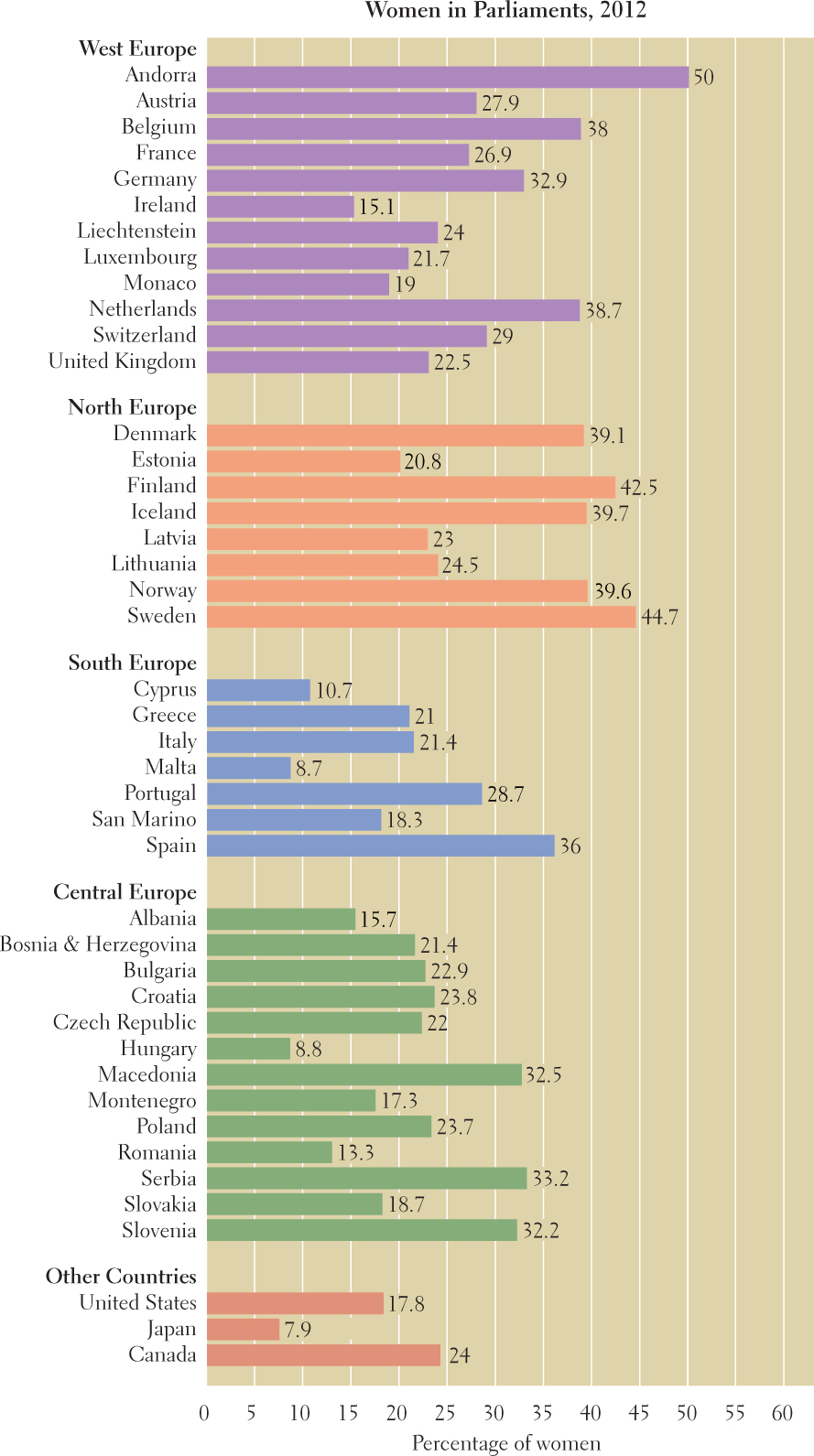

Many EU policies encourage gender equality. Managerial posts in the EU bureaucracy are increasingly held by women, and well over half the university graduates in Europe are now women. Despite this, the political influence and economic well-being of European women lag behind those of European men. In most European national parliaments, women make up less than a third of elected representatives. Only in North Europe, where several women have served as heads of government, do women come anywhere close to filling 50 percent of the seats in the legislature (Figure 4.25). In West Europe, the United Kingdom has had several female officials in high office, but elsewhere in the region this trend is only beginning. In 2009, Germany reelected Angela Merkel as its first woman chancellor (prime minister); in France, in 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy defeated female opponent Ségolène Royal, but then appointed women to a number of French cabinet-level positions. In 2012, fully one half of newly elected President François Hollande’s cabinet was female. In 2013, Slovenia chose Alenka Bratušek as prime minister and for the first time elected a parliament that is nearly one-third women. Still, across Europe, women generally serve only in the lower ranks of government bureaucracies, where they implement policy but have limited power to formulate policy.

Although change is clearly underway in the European Union, economic empowerment for women has been slow on many fronts. For example, in 2006, unemployment was higher among women than among men in all but a few countries (the United Kingdom, Germany, the Baltic Republics, Ireland, Norway, and Romania), where the differences were slight—and 32 percent of women’s jobs were part time, as opposed to only 7 percent of men’s jobs. Throughout the European Union, women are paid less than men for equal work, despite the fact that young women tend to be more highly educated than young men.

Norway leads Europe in redefining gender in society. It does this by directing much of its most innovative work on gender equality toward advancing men’s rights in traditional women’s arenas. For example, men now have the right to at least a month of paternity leave with a newborn or adopted child. This policy recognizes a father’s responsibility in child rearing and provides a chance for father and child to bond early in life.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

European Women in Leadership Positions

In 1986, Gro Harlem Brundtland, a physician, became Norway’s first female prime minister; she appointed women to 44 percent of all cabinet posts, thus making Norway the first country in modern times to have such a high proportion of women in important government policy-making positions. By 2013, women made up 39.6 percent of Norway’s parliament (Sweden had 44.7 percent; Finland 42.5 percent; and Iceland 39.7 percent). Norway also requires a minimum of 40 percent representation by each sex on all public boards and committees. Even though the rule has not yet been achieved in all cases, female representation averages over 35 percent for state and municipal agencies. In addition, employment ads are required to be gender neutral, and all advertising must be nondiscriminatory.

Social Welfare Systems and Their Outcomes

social welfare (in the European Union, social protection) in Europe, tax-supported systems that provide citizens with benefits such as health care, affordable higher education and housing, pensions, and child care

In nearly all European countries, tax-supported systems of social welfare or social protection (the EU term) provide all citizens with basic health care; free or low-cost higher education; affordable housing; old age, survivor, and disability benefits; and generous unemployment and pension benefits. Europeans generally pay much higher taxes than North Americans (the rate for EU countries is about 40 percent of GDP; for the United States, 27 percent; and for Canada, 30 percent); in return, they expect more in services. In some cases, European governments are able to deliver services more cheaply than the “free market” does elsewhere. For example, the European Union spends on average about $3000 per person for health care, while the United States spends more than $7000. Even at this much lower cost, the European Union has more doctors, more acute-care hospital beds per citizen, and better outcomes than the United States in terms of life expectancy and infant mortality.

Europeans do not agree on the goals of these welfare systems, or on just how generous they should be. Some argue that Europe can no longer afford high taxes if it is to remain competitive in the global market. Others say that Europe’s economic success and high standards of living are the direct result of the social contract to take care of basic human needs for all. The debate has been resolved differently in different parts of Europe, and the resulting regional differences have become a source of concern in the European Union. With open borders, unequal benefits can encourage those in need to flock to a country with a generous welfare system and overburden the taxpayers there.

European welfare systems can be classified into four basic categories (Figure 4.26). Social democratic welfare systems, common in Scandinavia, are the most generous systems. They attempt to achieve equality across gender and class lines by providing extensive health care, education, housing, and child and elder care benefits to all citizens from cradle to grave. Child care is widely available, in part to help women enter the labor market. But early childhood training, a key feature of this system, is also meant to ensure that in adulthood every citizen will be able to contribute to the best of his or her highest capability, and that citizens will not develop criminal behavior or drug abuse. While finding comparable data is very difficult, surveys of crime victims in Scandinavia and the European Union show that generally the rate of crime in Scandinavia is lower than in other parts of Europe.

The goal of conservative and modest welfare systems is to provide a minimum standard of living for all citizens. These systems are common in the countries of West Europe. The state assists those in need but does not try to assist upward mobility. For example, college education is free or heavily subsidized for all, but strict entrance requirements in some disciplines can be hard for the poor to meet. State-supported health care and retirement pensions are available to all, but although there are movements to change these systems, they still reinforce the traditional “housewife contract” by assuming that women will stay home and take care of children, the sick, and the elderly. The “modest” system in the United Kingdom is considered slightly less generous than the “conservative” systems found elsewhere in West Europe. The two are combined here but not in Figure 4.26.

In countries with rudimentary welfare systems, citizens are not considered to inherently have the right to government-sponsored support. They are found primarily in South Europe and in Ireland. Here, local governments provide some services or income for those in need, but the availability of such services varies widely, even within a country. The state assumes that when people are in need, their relatives and friends will provide the necessary support. The state also assumes that women work only part time, and thus are available to provide child care and other social services for free. Such ideas reinforce the custom of paying women lower wages than men.

Post-Communist welfare systems prevail in the countries of Central Europe. During the Communist era, these systems were comprehensive, resembling the cradle-to-grave social democratic system in Scandinavia, except that women were pressured to work outside the home. Benefits often extended to nearly free apartments, health care, state-supported pensions, subsidized food and fuel, and early retirement. However, in the post-Communist era, state funding has collapsed, forcing many to do without basic necessities. In many post-Communist countries, welfare systems are now being revised, but usually with an eye to reducing benefits and extending work lives past age 65.

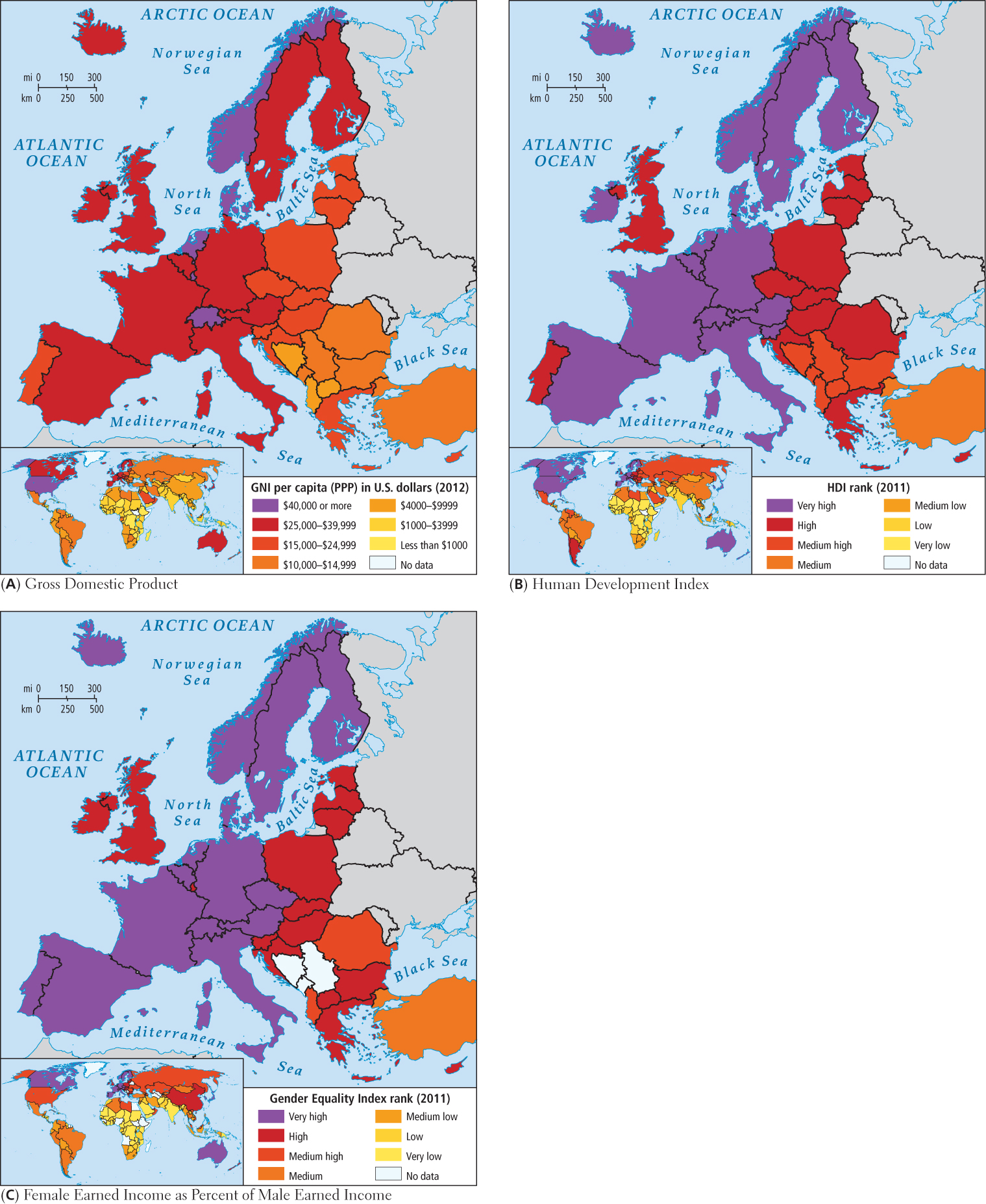

Geographic Patterns of Human Well-BeingTo a significant extent, the social welfare policies described above affect patterns of well-being, which, not surprisingly, have a geographical pattern. As we have observed, although Europe is one of the richest regions on Earth, there is still considerable disparity in wealth and well-being. GNI per capita is one measure of well-being because it shows in a general way how much people in a country have to spend on necessities, but it is an average figure and does not indicate how income is distributed. As a result, GNI per capita provides no way to determine if a few are rich and most poor, or if income is more equally apportioned.

Figure 4.27A, which shows GNI per capita (PPP) for all of Europe, illustrates two points. Most of the region has a GNI of at least $10,000 per capita, and only in three small countries in southeastern Europe—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia—is the GNI less than $10,000 per capita. West and North Europe (except for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) are the wealthiest regions. It is worth noting that Greece, which in the 1970s was still quite poor, joined the European Union in 1981 and began to realign its economy (industrializing, reducing its debt and rate of inflation) in order to meet EU specifications. While it is remarkable that in fewer than 30 years Greece appeared to have joined the ranks of Europe’s wealthiest countries, in 2010, the extent to which Greece’s prosperity was financed with expensive borrowing was revealed. These huge debt obligations have lowered the standard of living in Greece, at least for a while. The world map inset shows how Europe ranks in comparison to other parts of the world.

Figure 4.27B depicts the ranks of European countries in the United Nations Human Development Index (UN HDI), which is a calculation (based on adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment) of how well a country provides for the well-being of its citizens. It is possible to have a high GNI rank and a lower HDI rank if social services are inadequately distributed or if there is a wide disparity of wealth. Although the Figure 4.27A and B maps (of GNI per capita and HDI, respectively) look very similar, there are only a few countries in Europe that have both a high GNI and a high HDI—Norway, Lichtenstein, and Luxembourg. Most countries have a GNI ranking that is lower than their HDI rank, which indicates that all of these countries, regardless of their actual wealth, provide for their people relatively well, and wealth disparity is under control. In many cases this is because the countries have strong social safety nets or were until recently in communist societies that emphasized meeting basic needs for all.

The United Nations is not currently (2013) making data available on male and female earned income, but the reader should be aware that data from many agencies show that nowhere on Earth are the average wages of women and men equal. The UN data now uses the Gender Equality Index (GEI), which is based on reproductive health, political and educational empowerment, and labor-force participation (Figure 4.27C). European countries generally rank high, but some countries (Ireland, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, Malta, all of Central Europe, plus Greece), have a GEI ranking that is markedly lower than the rest of Europe. This raises concerns about equality between genders in these countries. On the other hand, many countries rank higher on the GEI scale than they do on the HDI. There is still cause for concern even in these countries, given what we know about ubiquitous disparities between female and male incomes, but in access to health care, education, and empowerment, they may be closer to equality between males and females.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Europe’s cities are world famous for their architecture, economic dynamism, and cultural vitality. Many are quite ancient but have expanded in recent decades, with large apartment blocks connected by public transport to the old city centers. In West, North, and South Europe, about 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas.

Europe’s cities are world famous for their architecture, economic dynamism, and cultural vitality. Many are quite ancient but have expanded in recent decades, with large apartment blocks connected by public transport to the old city centers. In West, North, and South Europe, about 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas. Geographic Insight 6Population and Gender Europeans are choosing to have fewer children; as a result, the population as a whole is aging. Small families are in part a result of women pursuing careers that require post-secondary education.

Geographic Insight 6Population and Gender Europeans are choosing to have fewer children; as a result, the population as a whole is aging. Small families are in part a result of women pursuing careers that require post-secondary education. Because Europe’s population is not growing and the number of consumers is staying the same or decreasing, economies may contract over time. Some governments now encourage larger families, often to no avail, through generous maternity and paternity leave (up to 10 months with full pay), free day care, and other incentives.

Because Europe’s population is not growing and the number of consumers is staying the same or decreasing, economies may contract over time. Some governments now encourage larger families, often to no avail, through generous maternity and paternity leave (up to 10 months with full pay), free day care, and other incentives. It is widely recognized that immigrants are necessary to Europe’s future, as workers and as a way to counter aging populations. Yet Europeans are ambivalent about accepting people of other cultures into their midst. They are more willing to accept outsiders if they assimilate in all ways to European culture.

It is widely recognized that immigrants are necessary to Europe’s future, as workers and as a way to counter aging populations. Yet Europeans are ambivalent about accepting people of other cultures into their midst. They are more willing to accept outsiders if they assimilate in all ways to European culture. Despite high levels of education, the political influence and economic well-being of European women lag behind those of European men; only a small percentage of women are in elected positions, and women have less access to jobs with high salaries.

Despite high levels of education, the political influence and economic well-being of European women lag behind those of European men; only a small percentage of women are in elected positions, and women have less access to jobs with high salaries. Europeans generally value social safety nets for all citizens, and standards of human well-being are generally high across Europe. Because Europeans vary in the types of systems they are willing to pay for, levels of well-being vary. All safety nets are currently being reevaluated.

Europeans generally value social safety nets for all citizens, and standards of human well-being are generally high across Europe. Because Europeans vary in the types of systems they are willing to pay for, levels of well-being vary. All safety nets are currently being reevaluated.