Russia

In the post-Soviet era, Russian influence in the region remains strong, even as the post-Soviet states have begun to construct their own economies and political identities. Russia is still the largest country on Earth in terms of area—nearly twice the size of Canada, the United States, or China—and is rich in natural resources. With 143 million people, it ranks eighth in the world in population. For convenience, we have divided Russia into three parts: European Russia; Siberian Russia, which composes about half the landmass east of the Urals; and the Russian Far East. There is no clear boundary between Siberian Russia and the Far East; in fact, the term Siberia is sometimes used for Russian territories all the way to the Pacific.

European Russia

European Russia is the area of Russia that shares the eastern part of the North European Plain with Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova (Figure 5.27). It is usually considered the heart of Russia because it is here that early Slavic peoples established what became the Russian empire, with its center in Moscow. Although it occupies only about one-fifth of the total territory of present-day Russia, European Russia has most of the industry, the best agricultural land, and about 70 percent (100 million people) of the population of the Russian Federation. A tiny exclave of European Russia is Kaliningrad, located on the Baltic Sea between Lithuania and Poland. The Kaliningrad port is important to Russia because it is free of ice for more of the year than St. Petersburg and serves as an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean. The port of Murmansk, which faces the Arctic Ocean, also connects to the Atlantic; because of warm ocean currents, it is ice-free year around despite its location north of the Arctic. However, Murmansk is located far away from main commercial routes; it is mostly important for military purposes.

The vast majority of European Russians live in cities, their parents and grandparents having left rural areas when Stalin collectivized agriculture and established heavy industry. Most of these people went to work in one of four major industrial regions that were chosen by central planners for their accessibility and their location near crucial mineral resources. One industrial region is centered on Moscow; another in the Ural Mountains and foothills (part of this zone lies in Siberian Russia); a third along the Volga River from Kazan to Volgograd; and the fourth just north of the Black Sea, extending into Ukraine around Donetsk (see Figure 5.15).

The most densely occupied part of European Russia—stretching from St. Petersburg on the Baltic, south to Caucasia, and east to the Urals (see Figure 5.20)—coincides with that part of the continental interior that has the most favorable climate (see Figure 5.5). Even so, because the region lies so far to the north (Moscow is at a latitude 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of Edmonton, Canada) and in a continental interior, the winters are rather long and harsh and the summers short and mild.

Urban Life and Patterns in European Russia

Moscow remains at the heart of Russian life. The city has grown in the post-Soviet era; in 2010, about 11.5 million people lived within the city limits and another 4.6 million lived in the metropolitan area, making Moscow the largest city in greater Europe. Always a center of Russian culture, Moscow has so changed since 1991 that a common saying is “Moscow and Russia are two different countries.” The availability of goods—food, electronics, furniture, appliances, clothing, automobiles, and especially luxury products and entertainment of all types—has exploded. Prices are higher here than in most Russian cities and rising at a rate of about 15 percent per year. The criminals are more concentrated, more innovative, and more violent in Moscow. Entrepreneurs are especially active. While the city is full of apparently affluent, educated young people, many are merely “dressed for success” and are living on credit.

The privatization of real estate in Moscow gives an interesting insight into pre- and post-Soviet circumstances. During the Communist era, all housing was state owned and there was a general housing shortage; thousands of families were always waiting for housing, some for more than 10 years. Most apartments were built after the mid-1950s in large, shoddily constructed gray concrete blocks; the units included one to three rooms that housed one to four (or more) people. In 1991, the government allowed residents of Moscow to acquire, free, about 250 square feet (23 square meters) of usable living space per person—about the size of a typical American living room. Most families simply took ownership of the apartments in which they had been living, so that by 1995, a majority of Muscovite families owned their apartments. A lively real estate market quickly emerged, with a rising wealthy elite willing to pay for an apartment in the city center. Purchase prices in excess of U.S.$1,000,000 are not unusual today. Rents also skyrocketed. Those who could find alternative housing for themselves made tidy sums simply by renting out or selling their center-city apartments (see Figure 5.27A). The demand for commercial space for private businesses reduced the number of dwelling units, thus exacerbating the housing shortage. As the supply of space tightened, criminal efforts to acquire property through intimidation increased.

St. Petersburg, renamed Leningrad during most of the Communist period (1924–1991), is European Russia’s second-largest city, with about 5 million people. It is a shipbuilding and industrial city located at the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland, on the Baltic Sea. Czar Peter the Great ordered the city built in 1703 as part of his effort to Europeanize Russia; from 1713 to 1918, it served as the Russian capital, and it has been one of Russia’s cultural centers ever since. The city has a rich architectural heritage, including many palaces and public parks; crisscrossed with canals, it gives the ambience of Venice. Since 1991, it has been undergoing a renaissance; the transportation system is being refurbished, urban malls are proliferating, and historic sites are being renovated. The czars’ Winter Palace, now called the Hermitage Museum, houses one of the world’s most important art collections (see Figure 5.10C).

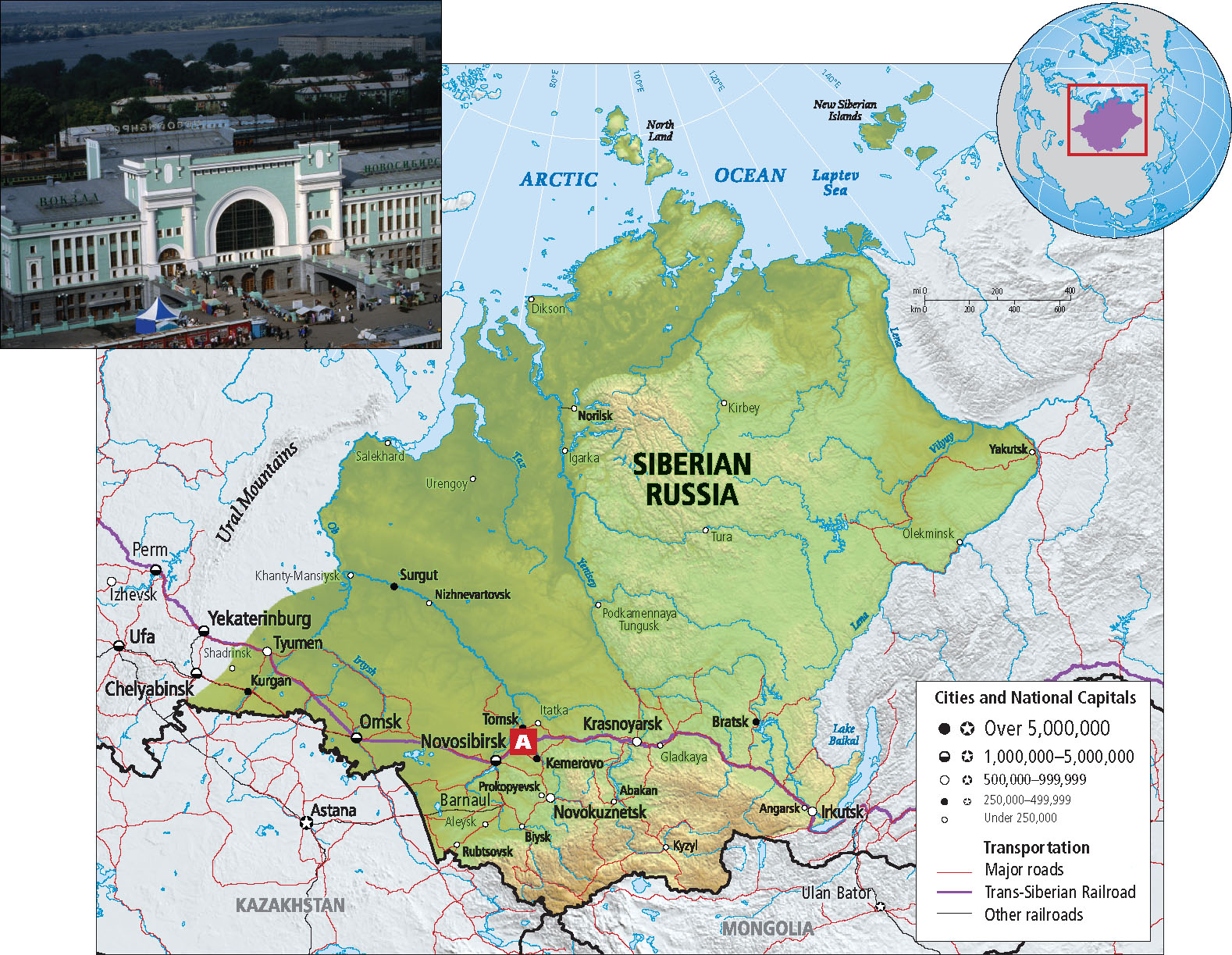

Siberian Russia

Siberia encompasses the West Siberian Plain beyond the Urals and about half the Central Siberian Plateau (Figure 5.28). It is so cold that 60 percent of the land has permafrost, which now appears to be melting due to climate change. This vast central portion of Russia is home to just 31 million people, many of whom moved into the region from European Russia. With the exception of Norilsk, settlement is concentrated in cities in the somewhat warmer southern quarter.

For millennia, Siberia has been a land of wetlands and quiet, majestic forests. The Siberian taiga forest, south of the permafrost range, is one of the largest in the world and is thought to sequester a great deal of atmospheric carbon. Like all economic activities, forest harvesting declined during the post-Communist period, but as the economy has improved recently, more clear-cutting is taking place, which lowers the rate of carbon sequestration, the act of capturing and storing carbon for later use. In the northern zones closer to the Arctic, global warming appears to be melting the permafrost, and water that used to be retained in lakes is escaping downstream. Another effect is that organic material that used to be frozen is now exposed to the air, which results in the release of methane and other greenhouse gases. Basically, global warming generates more greenhouse gas emissions, which further heats the climate through this ecological feedback mechanism.

Although the entire area of Russia east of the Urals continues to be occupied by a scattering of indigenous groups—some still practicing nomadic herding, hunting, and gathering—during the Soviet era, Siberian Russia became dotted with bleak urban landscapes and industrial squalor (see the discussion of Norilsk). This is the legacy of the Soviet effort to claim territory from the indigenous peoples by settling it with Russians and to establish industries that would exploit Siberia’s valuable mineral, fish, game, and timber resources. Novosibirsk, Siberia’s twentieth-century capital and financial center, is an example of the result of this policy.

Novosibirsk, the largest Russian city east of the Urals (1.5 million people), is some 1600 miles (2500 kilometers) east of Moscow and is a major stop along the Trans-Siberian Railroad (see Figure 5.28A). This isolated commercial center has the highest concentration of industry between the Urals and the Pacific. During the Cold War, it was a center for strategic industries such as optics and weaponry; it contained more than 200 heavy industry plants. These factories are now infamous for being obsolete and having high rates of pollution, but they also can potentially be profitable in the future if they are privatized and reorganized. Novosibirsk’s banks and financial services are drawing outside investors interested in acquiring factories in the vicinity.

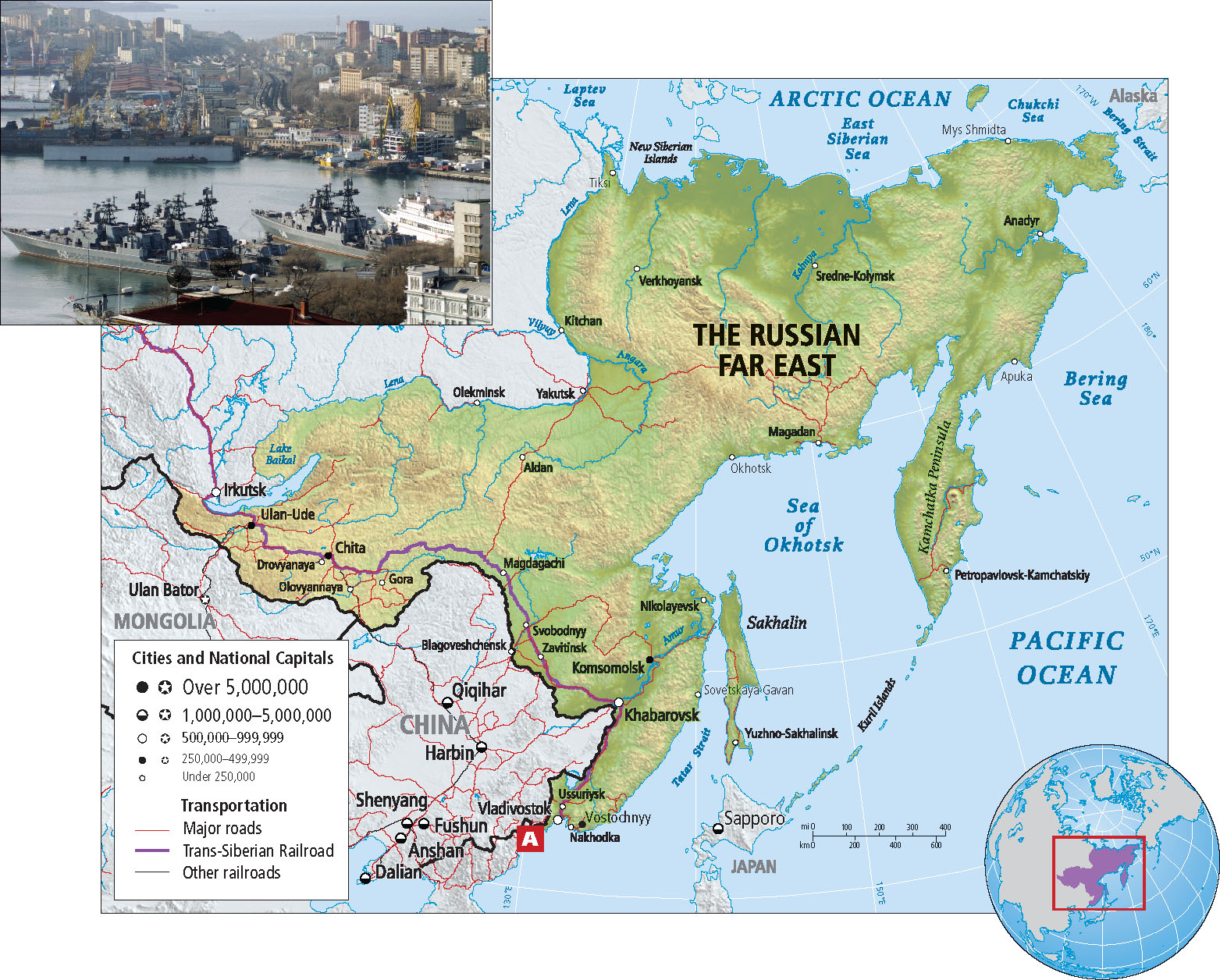

The Russian Far East

Here in this extensive territory of mountain plateaus with long coastlines on the Pacific and Arctic oceans (Figure 5.29), almost 90 percent of the land is permafrost. The coastal volcanic mountains stop the warmer Pacific air from moderating the Arctic cold that spreads deep into the continent. Making up slightly over one-third of the entire country of Russia, this area is nearly two-thirds the size of the United States. If the population of 6.3 million were evenly distributed across the land, there would be just 2.6 persons per square mile (1 per square kilometer), but 75 percent of the people live in just a few cities along the Trans-Siberian Railroad and on the Pacific coast.

The residents of the Russian Far East are primarily immigrants and exiles, some descended from those sentenced to the region for perceived misdeeds in the Soviet era (some of the prison camps made famous in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book The Gulag Archipelago were along the Kolyma River). These Far Easterners worked in timber and mineral extraction enterprises and in isolated industrial enclaves. Since the 1980s, many immigrants have headed for cities along the Pacific coast, especially Nakhodka and Vladivostok, near North Korea. Vladivostok is strategically important as a naval base and is also Russia’s largest Pacific port (see Figure 5.29A). Since serfdom never intruded into the Far East, there is a spirit of independence and entrepreneurship that is rare elsewhere in Russia.

The interior of the Russian Far East has many resources, but it has not been developed because of its distance from European Russia and its difficult physical environments. Only 1 percent of the territory is suitable for agriculture, mostly along the Pacific coast and in the Amur River basin. Relatively unexploited stands of timber cover 45 percent of the area. The wilderness supports many endangered species, such as the Siberian tiger, the Far Eastern leopard, and the Kamchatka snow sheep. The region’s timber, coal, natural gas, oil, and minerals first attracted Soviet central planners, and now attract private investors. The proximity to Chinese markets has increased timber harvesting, some of it illegally logged. The American multinational company Exxon has started oil production off Sakhalin Island that is destined for Asian markets. Since 2009, liquefied natural gas has been shipped to Japan, which is located just 30 miles south of Sakhalin. With no pipelines in place, and with few domestic energy sources, Japan is willing to pay the extra price for natural gas that has to be liquefied before it can be transported on oceangoing tankers.

The region has further potential for linkages with the greater Pacific Rim. In recent decades, port facilities on the Pacific coast have made the region more accessible to Asia. China and Japan (see Figure 5.29), both of which need energy resources, wanted an oil pipeline from Siberia to either China or the Russian Pacific coast, very close to Japan. The pipeline is now expected to terminate at Nakhodka on the Russian Pacific coast, which will give Russia access to petroleum markets in the western Pacific, but a spur to China will supply that country as well. Russia is also considering a rail link across China to North Korea and Vladivostok, the Russian outpost city on the Pacific. Some geographers and economists speculate that, because of its rich resource reserves and its location so far from the Russian core, the Russian Far East is likely to integrate economically with other Pacific Rim nations, and might eventually detach itself politically from European Russia. So far, areas in Siberia and the Far East that are not part of the growing natural resource economy have suffered from population decline, and migrants are primarily moving to the larger cities in European Russia.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Russia, the largest country in the world in area, has three principal geographic divisions, and although linked politically, each has distinct economies and cultural traditions.

Russia, the largest country in the world in area, has three principal geographic divisions, and although linked politically, each has distinct economies and cultural traditions. Moscow is Russia’s fast-growing primate city; it attracts an affluent, young, and educated population.

Moscow is Russia’s fast-growing primate city; it attracts an affluent, young, and educated population. Siberia and the Far East are sparsely populated, with only a handful of isolated commercial and industrial centers between the Urals and the Pacific. The natural resource economy of these areas is increasingly oriented toward Asia.

Siberia and the Far East are sparsely populated, with only a handful of isolated commercial and industrial centers between the Urals and the Pacific. The natural resource economy of these areas is increasingly oriented toward Asia. Globalization and Development The fall of the Soviet Union and the economic reforms that followed have increased disparities of wealth and made the region dependent on energy exports.

Globalization and Development The fall of the Soviet Union and the economic reforms that followed have increased disparities of wealth and made the region dependent on energy exports.