The Central Asian States

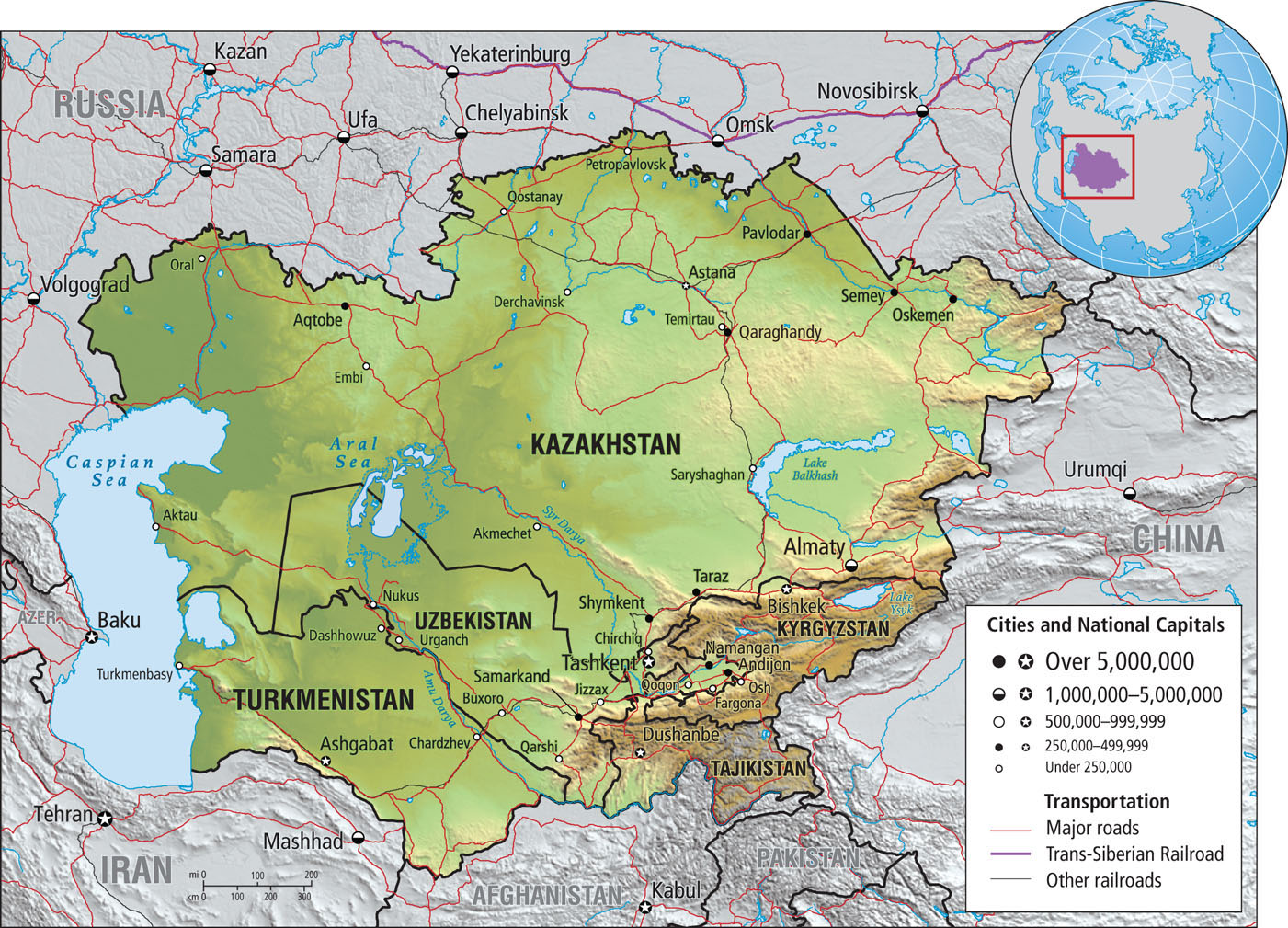

Since 1991, following nearly 12 decades of Russian colonialism, five independent nations have emerged in Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan (Figure 5.33). Each of these new nations has traditions that are recognizably different from the others, yet all draw on the deep, common traditions of this ancient region.

Physical Setting

Central Asia lies in the center of the Eurasian continent, in the rain shadow of the lofty mountains that lie to the south in Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.5. Its dry continental climate is a reflection of this location. What rain there is falls mainly in the north, on the Kazakh steppes (see Figure 5.5B), where wide grasslands now support limited grain agriculture and large herds of sheep, goats, and horses. In the south are deserts crossed by rivers that carry glacial meltwater from the high peaks still farther to the southeast. In Soviet times, these rivers were tapped to irrigate huge fields of cotton and smaller fields of wheat and other grains (see the discussion of irrigation and the Aral Sea). In southern settlements, houses have food gardens walled to protect against drying winds. These gardens nurture many types of melons, herbs, onions and garlic, and tree crops—plums, pistachios, apricots, and apples—all of which were first domesticated in this region in ancient times.

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are largely low-lying plains. Kazakhstan has plains in the north and uplands in the southeast that grade into high mountains. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan lie high in the Hindu Kush, the Pamir, and Tien Shan mountains to the southeast of Kazakhstan. These two countries have exceedingly rugged landscapes: Tajikistan’s elevations go from near sea level to more than 22,000 feet (6705 meters), and those in Kyrgyzstan are similar. Both offer little in economic potential; Tajikistan is the poorest country in the entire region and has undergone numerous changes in government and a 1990s civil war involving many political and religious factions, from which the country has not yet recovered.

Central Asia in World History

Civilization flourished in Central Asia long before it did in lands to the north. The ancient Silk Road, a continuously shifting ribbon of trade routes connecting China with the fringes of Europe, operated for thousands of years, diffusing ideas and technology from place to place (see Figure 5.9; see also Figure 1.6 and the discussion of a hypothetical Central Asia region). Vestiges of nomadic life, common in the days of the Silk Road, can still be seen from Uzbekistan to Siberia. The yurt, a portable dwelling of felt on a collapsible wood frame, is a type of domestic structure that has been used for more than 2000 years and is still being used today (Figure 5.34). Modern versions of ancient trading cities still dot the land; Bukhara, which has been in existence as a settlement for 5000 years, is one such city (Figure 5.35). Commerce along the Silk Road diminished as trade shifted to sea lanes after 1500. Central Asia then entered a long period of stagnation until, in the mid-nineteenth century, czarist Russia developed an interest in the region’s major export crop, cotton.

Russian imperial agents built modern mechanized textile mills to replace small-scale textile firms that had employed people to do traditional cotton, wool, and silk weaving (Figure 5.36). As part of the Russification process, the new mills employed imported Russians and were often located in newly built Russian towns alongside railroad lines. Consequently, these industries benefited few Central Asians. In rural areas, cotton fields often replaced the wheat fields that had fed local people. Occasional famines struck whenever people could not afford imported food or when food supplies were interrupted.

Russian domination intensified in the Soviet era, after 1918. Only a few Central Asian political leaders actually joined the Communist Party; those who did were thoroughly Russified. Kazakhstan, with a long border with Russia, is the most Russified of the Central Asian states today; a quarter of the population is ethnically Russian, the Russian language has official status in the country, and Orthodox Christianity is as common as Islam. The practice of Islam, dominant in the other Central Asian states, while officially tolerated during the Soviet era, was undermined by the Communist government’s promotion of atheism. Fearing that the open practice of Islam would encourage pan-Islamism and weaken Russia’s hold on the area, Russia restricted Islamic practices, such as access to mosques, pilgrimages to Makkah (Mecca), and Muslim-influenced dress.

For Central Asia, the transition since independence in 1991 has been rocky. Some conditions of daily life have deteriorated significantly. Trade patterns were interrupted; factories closed; transportation and services, never well developed, declined; and poverty spread as health standards fell. Although elections are held and free markets are opening up opportunities for entrepreneurship, the government remains authoritarian and patriarchal, and the heads of state are autocratic. Elections are routinely hijacked by fraudulent vote counts. Most Central Asian governments, though nominally Muslim themselves, fear Islamic fundamentalism and repress even moderate Muslims. Three of the countries—Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan—border volatile Afghanistan. The conflict in Afghanistan has the potential to create a “spillover” effect of religious strife into Central Asia.

Russia has sought to maintain a strong influence on Central Asia, but growing international interest in the region’s oil and gas resources is challenging that influence. In Kazakhstan especially, large oil and gas reserves are driving rapid economic growth. GDP per capita (PPP) more than doubled between 2000 and 2010, and the government plans for similar growth in the future, based on the development of new oilfields in western Kazakhstan near the Caspian Sea and the construction of new pipelines (see Figure 5.14). Since the Soviet days, Kazakhstan’s existing pipeline network has connected with Russia, but a new pipeline also connects to China. Part of Kazakhstan’s new wealth is being invested in constructing a lavish new capital, Astana (see the vignette). Oil wealth is also beginning to make a difference in human well-being, as is reflected in Kazakhstan’s relatively high HDI rank, which is similar to that of Russia and significantly above those of the other Central Asian states.

105. PRIZE-WINNING IDEA PAYING DIVIDENDS IN KYRGYZSTAN

105. PRIZE-WINNING IDEA PAYING DIVIDENDS IN KYRGYZSTAN

113. UZBEKISTAN’S STRICT BORDER REGIME SEPARATES UZBEK FROM UZBEK

113. UZBEKISTAN’S STRICT BORDER REGIME SEPARATES UZBEK FROM UZBEK

122. NEW CAPITAL CITY DRAWS ATTENTION IN KAZAKHSTAN

122. NEW CAPITAL CITY DRAWS ATTENTION IN KAZAKHSTAN

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Free Market—Persistence of an Ancient Central Asian Invention

The Central Asian states appear to be finding their capitalist “legs” fairly quickly. As communism fades and the Russians leave, Central Asians are taking up old, market-based skills that have been part of their heritage since the ancient Silk Road days, when trade and long-distance travel were the heart of the economy. A largely contraband trade in consumer goods (clothes, electronics, cars) and illegal substances (from drugs to guns) with Iran, Afghanistan, and western China is blossoming. Through microcredit (small, low-interest loans to the poor), women are becoming involved in entrepreneurism. Opportunities to render services such as food vending (Figure 5.37), auto repair, transportation, and accommodations to tourists and traveling businesspeople are opening up for workers displaced in the transition. Meanwhile, all five states are negotiating with competing multinational oil companies to market Central Asian oil and gas to their best advantage. To the south, Turkmenistan has reestablished commercial ties with its neighbor Iran. The two countries are now major trading partners and the ongoing infrastructure projects that they have planned, such as railroads and pipelines, will continue to strengthen their ties.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The five newly independent (since 1991) countries in predominantly Muslim Central Asia remain relatively poor and are governed by autocratic leaders, although a fossil fuel–based economy, especially in Kazakhstan, has generated economic growth and development.

The five newly independent (since 1991) countries in predominantly Muslim Central Asia remain relatively poor and are governed by autocratic leaders, although a fossil fuel–based economy, especially in Kazakhstan, has generated economic growth and development. While Russia tries to maintain some control over these former territories, primarily through economic pressure, the countries are reconnecting with nearby Asian nations and are also taking up old, market-based skills that have been part of their heritage since the ancient Silk Road days, when trade and long-distance travel were the heart of the economy.

While Russia tries to maintain some control over these former territories, primarily through economic pressure, the countries are reconnecting with nearby Asian nations and are also taking up old, market-based skills that have been part of their heritage since the ancient Silk Road days, when trade and long-distance travel were the heart of the economy.