Physical Patterns

The physical features of Russia and the post-Soviet states vary greatly over the huge territory they encompass. The region bears some resemblance to North America in size, topography, climate, and vegetation. Even if Russia is only about three-quarters the size of the Soviet Union, it is still the largest country in the world, nearly twice the size of the second-largest country, Canada.

Landforms

Siberia a region of Russia that is located east of the Ural Mountains

steppes semiarid, grass-covered plains

The eastern extension of the North European Plain rolls low and flat from the Carpathian Mountains in Ukraine and Romania, 1200 miles (about 2000 kilometers) east to the Ural Mountains (see Figure 5.1A, C, D). The part of Russia west of the Urals is often called European Russia because the Ural Mountains are traditionally considered part of the indistinct border between Europe and Asia. European Russia is the most densely settled part of the entire region (see Figure 5.20) and its agricultural and industrial core. Its most important river is the Volga, which flows into the Caspian Sea. The Volga River and its tributaries form a major transportation route that connects many parts of the Russian North European Plain, including Moscow, to St. Petersburg and the Baltic and White seas in the north and to the Black and Caspian seas in the south (see Figure 5.1C).

The Ural Mountains extend in a fairly straight line south from the Arctic Ocean into Kazakhstan (see the Figure 5.1 map). The Urals, a low-lying range similar in elevation to the Appalachians, are not much of a barrier to humans and are only partially a barrier to nature (some European tree species do not extend east of the Urals). There are several easy passes across the mountains, and winds carry moisture all the way from the Atlantic into Siberia. Much of the Urals’ once-dense forest has been felled to build and fuel industrial cities.

permafrost permanently frozen soil that lies just a few feet beneath the surface

tundra a treeless area, between the ice cap and the tree line of arctic regions, where the subsoil is permanently frozen

The Central Siberian Plateau and the Pacific Mountain Zone, farther to the east, together equal the size of the United States (see Figure 5.1F, G). Permafrost prevails except along the Pacific coast. There, the ocean moderates temperatures; the many active volcanoes were and are created as the Pacific Plate sinks under the Eurasian Plate. Lightly populated places like the Kamchatka Peninsula, Sakhalin Island, and Sikhote-Alin on Russia’s southeastern Pacific coast are havens for wildlife.

To the south of the West Siberian Plain, steppes and deserts stretch from the Caspian Sea to the Chinese border. To the west of these grasslands are the Caucasus Mountains (see Figure 5.1B) and to the southeast facing China and Mongolia are a series of other mountain chains, including Pamir and Tien Shan. The rugged terrain has not deterred people from crossing these mountains. From the Caucasus to the Pamir and Tien Shan, for tens of thousands of years people have exchanged plants (apples, onions, citrus, rhubarb, wheat), animals (horses, sheep, goats, cattle), technologies (cultivation, animal breeding, portable shelter construction, rug and tapestry weaving), and religious belief systems (principally Islam and Buddhism, but also Christianity, Hinduism, and Judaism).

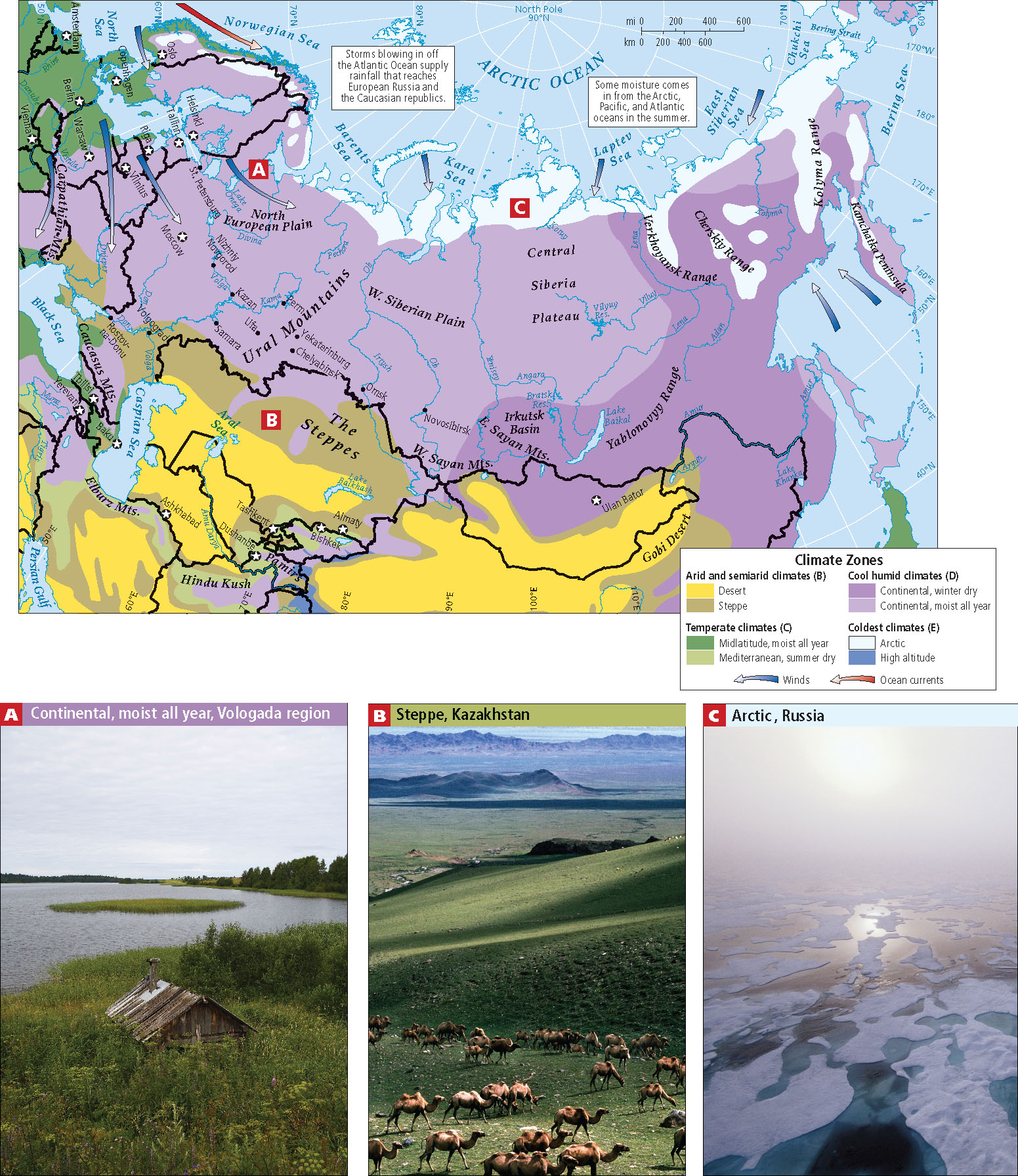

Climate and Vegetation

taiga subarctic coniferous forests

Because massive mountain ranges to the south block access to warm, wet air from the Indian Ocean, most rainfall in the entire region comes from storms that blow in from the Atlantic Ocean far to the west (see the Figure 5.5 map). But by the time these air masses arrive, most of their moisture has been squeezed out over Europe. A fair amount of rain does reach Ukraine, Belarus, European Russia (see Figure 5.5A), and the Caucasian republics; these regions are especially important food production (vegetables, fruits, and grain) areas. The natural vegetation in these western zones is open woodlands and grassland, though in ancient times, forests were common.

East of the Caucasus Mountains, the lands of Central Asia have semiarid to arid climates (see Figure 5.5B) influenced by their location in the middle of a very large continent. The summers are scorching and short, the winters intense. In the desert zones, daytime-to-nighttime temperatures can vary by 50°F (28°C) or more. Northern Kazakhstan produces grain and grazing animals. The more southern areas (southern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan) have grasslands (steppes), which are also used for herding. In modern times, these grasslands have been used for irrigated commercial agriculture that is dependent upon glacially fed rivers, but most land is not useful for farming. The climates in the more mountainous area where Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan meet are varied and support a number of small-scale agricultural activities, some of them commercial.

The construction of land transportation systems has long been held back by the climate of the region. In the north especially, it is difficult to build during the long, harsh winters, which eventually give way to a spring period called the rasputitsa, or the “quagmire season,” when melting permafrost (or, to a lesser extent, autumn rains) turns many roads and construction sites into impassable mud pits. Huge distances between populated places as well as the complex topography, especially in Siberia, add to the problem. As a result, few roads or railroads have ever been built outside western Russia (see Figure 5.15).