Environmental Issues

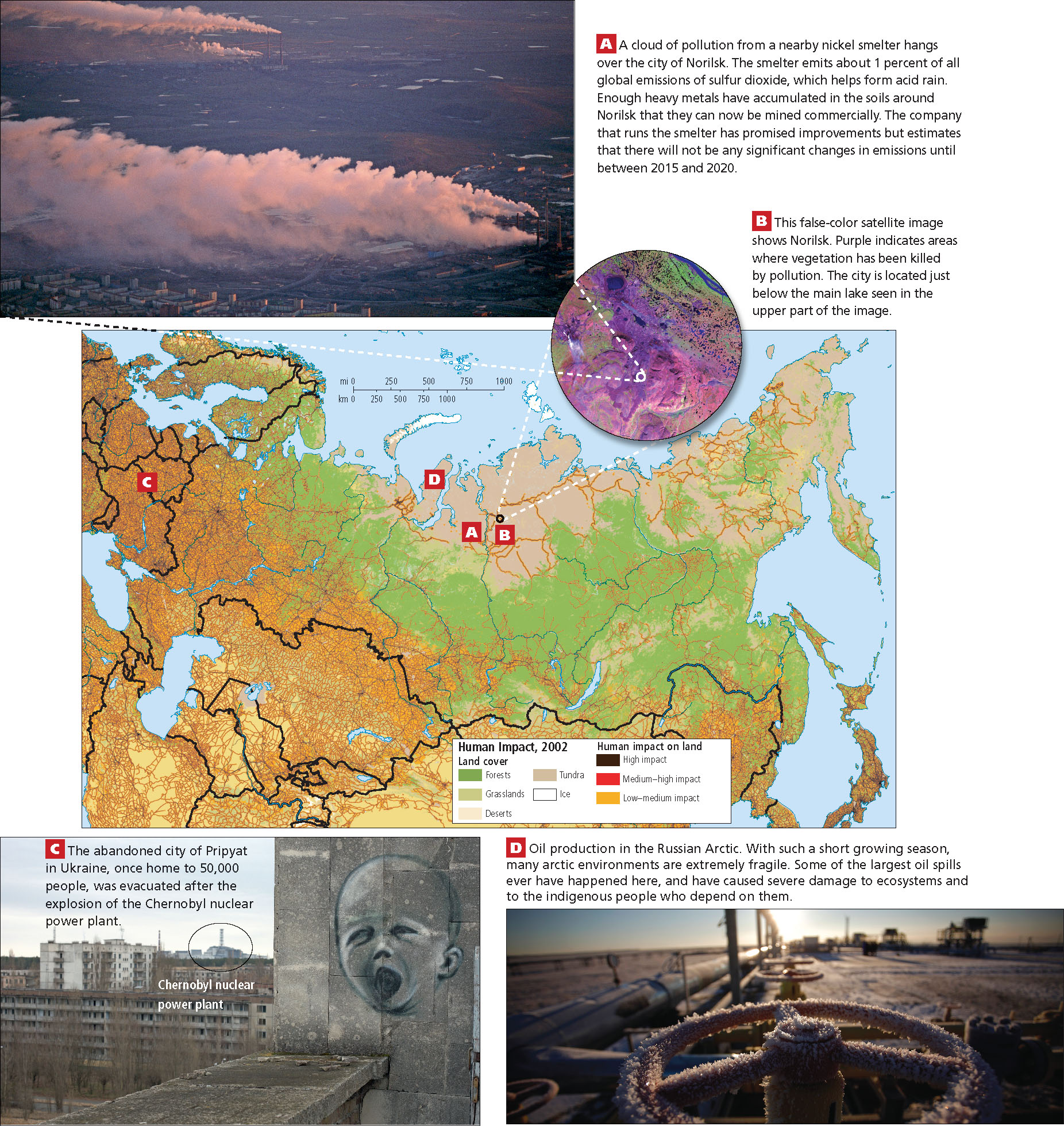

Soviet ideology held that nature was the servant of industrial and agricultural progress, and that humans should dominate nature on a grand scale. While this sentiment was common throughout much of the world at the time of the formation of the USSR, it does seem to have been taken further here than elsewhere. Joseph Stalin, leader of the USSR from 1922 to 1953 and a major architect of Soviet policy, is famous for having said, “We cannot expect charity from Nature. We must tear it from her.” During the Soviet years, huge dams, factories, and other industrial facilities were built without regard for their effect on the environment or on public health. Russia and the post-Soviet states now have some of the worst environmental problems in the world. By 2000, more than 35 million people in the region (15 percent of the population) were living in areas where the soil was poisoned and the air was dangerous to breathe (Figure 5.6A–C).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human impact on the biosphere in Russia and the post-Soviet states, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Why was Pripyat evacuated?

Why was Pripyat evacuated?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

In addition to oil pollution, from what other form of pollution has the arctic portion of this region suffered?

In addition to oil pollution, from what other form of pollution has the arctic portion of this region suffered?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the region’s governments, beset with myriad problems, have been both reluctant to address environmental issues and incapable of doing so. As one Russian environmentalist put it, “When people become more involved with their stomachs, they forget about ecology.” Pollution controls are complicated by a lack of funds and by an official unwillingness to correct past environmental abuses. Figure 5.6 shows just a few examples of human impacts on the region’s environment, most of which are related to ongoing industrial pollution (as in Norilsk, in Figure 5.6A, B) or failure to properly dismantle contaminated industrial sites made obsolete when a more market-based economy was introduced (as in Pripyat, Ukraine, in Figure 5.6C). The extraction and sale of oil and gas on the global market is now a major source of income for Russia and several of the post-Soviet states, yet very little attention is being paid even today to the environmental impact of this activity (see Figure 5.6D).

Urban and Industrial Pollution

Geographic Insight 1

Environment, Development, and Urbanization: Development and urbanization in this region have long taken precedence over environmental concerns. The region has severe environmental problems, especially in urban areas.

Urban and industrial pollution was ignored during Soviet times as cities expanded quickly—with workers flooding in from the countryside—to accommodate the new industries that often generated lethal levels of pollutants. During the authoritarian Soviet regime, citizens’ concerns about their living environment were suppressed, and this political environment did not allow for protests or an environmental movement as in North America and western Europe.

nonpoint sources of pollution diffuse sources of environmental contamination, such as untreated automobile exhaust, raw sewage, and agricultural chemicals, that drain from fields into water supplies

Some cities were built around industries that produce harmful by-products. The former chemical weapons–manufacturing center of Dzerzhinsk has been listed by the nonprofit Blacksmith Institute as one of the ten most polluted cities in the world. It is competing with the city of Norilsk, where much of the vegetation has been killed off around the city’s metal smelting complex—the largest facility of its kind in the world (see Figure 5.6B). Norilsk was the most polluted city in Russia as recently as 2011.

The Globalization of Nuclear Pollution

Russia and the post-Soviet states are also home to extensive nuclear pollution, and its effects have spread globally. The world’s worst nuclear disaster occurred in Ukraine in 1986, when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded. The explosion severely contaminated a vast area in northern Ukraine, southern Belarus, and Russia. It spread a cloud of radiation over much of Central Europe, Scandinavia, and eventually the entire planet. In the area surrounding Chernobyl, more than 300,000 people were evacuated from their homes, and the town of Pripyat, which used to be home to 50,000 people, has been an abandoned ghost town since the disaster (see Figure 5.6C). The ultimate health effects are impossible to assess exactly. The United Nations estimates that 6000 people developed cancer due to the accident, although many believe the number to be much higher.

278. SAFETY AT THE CENTER OF NUCLEAR POWER OPERATIONS WORLDWIDE

278. SAFETY AT THE CENTER OF NUCLEAR POWER OPERATIONS WORLDWIDE

When the Soviet Union collapsed, many of the post-Soviet states inherited nuclear facilities and even nuclear weapons. One such country is Kazakhstan (see Figure 5.3). Remote areas of eastern Kazakhstan used to serve as a testing ground for Soviet nuclear devices. The residents were sparsely distributed and no one took the trouble to protect them from nuclear radiation. A museum in Kazakhstan now displays the preserved remains of hundreds of deformed human fetuses and newborns. On the positive side, Kazakhstan has disarmed the nuclear warheads that it inherited from the Soviet Union and has worked with U.S. authorities to safeguard remaining nuclear weapons material. Kazakhstan plans to use its nuclear technology to become a global player in the nuclear energy sector. The country is already the single biggest producer of uranium in the world, generating 35 percent of the global production total. In addition to mining and exporting the raw material, Kazakhstan also wants to produce nuclear fuel both for global markets and domestic nuclear power plants, and develop commercial repositories for radioactive waste from other countries. However, the global appetite for nuclear expansion after the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan remains uncertain, and no reliably safe system has yet been found for storing nuclear waste until it is no longer radioactive. Environmental and human rights NGOs have raised strong opposition, pointing to the region’s poor environmental track record. Kazakhstan’s population may also be suspicious of nuclear power because they have lived for a long time with land poisoned by radioactive waste.

The Globalization of Resource Extraction and Environmental Degradation

Russia and the post-Soviet states have considerable natural and mineral resources (see Figure 5.14). Russia itself has the world’s largest natural gas reserves, major oil deposits, and forests that stretch across the northern reaches of the continent. Russia also has major deposits of coal and industrial minerals such as iron ore and nickel. The Central Asian states share substantial deposits of oil and gas, which are centered on the Caspian Sea and extend east toward China. The value of all these resources is determined in the global marketplace, and their extraction affects the global environment.

Despite obvious environmental problems, cities like Norilsk (see Figure 5.6A), which sits on huge mineral deposits, continue to attract investment crucial to the new Russian economy. The area is rich in nickel—used in steel and other industrial products—and other minerals, such as copper. Norilsk Nickel, a company that was privatized at the end of communism and is now the largest producer of nickel in the world, dominates the city. Because the Russian government considers many minerals to be a strategic resource for the country, it limits foreign ownership in the industry. Partly because of that, and because of its extensive and profitable home base, Russian-controlled Norilsk Nickel has globalized, despite its poor environmental record, by purchasing mining operations in Australia, Botswana, Finland, the United States, and South Africa. The company employs over 80,000 people worldwide.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Controlling Nuclear Material

In the post-9/11 world, concern spread that military corruption in this region could put nuclear weapons from the former Soviet arsenal into the hands of terrorists. After huge military-funding cuts, weapons, uniforms, and even military rations were routinely sold on the black market. In 2007, Russian smugglers were caught trying to sell nuclear materials on the black market. Recent developments are more encouraging. In an effort to fight corruption and the temptation to sell nuclear materials in the black market, the Russian government has given impoverished military personnel long-delayed pay raises or termination compensation. In addition, all countries in the region are now cooperating with the International Atomic Energy Agency in controlling nuclear material.

Water Issues

Water was once assumed to be inexhaustible and usable for endless purposes, while needing little maintenance. Now most countries in this region recognize it as a vital resource.

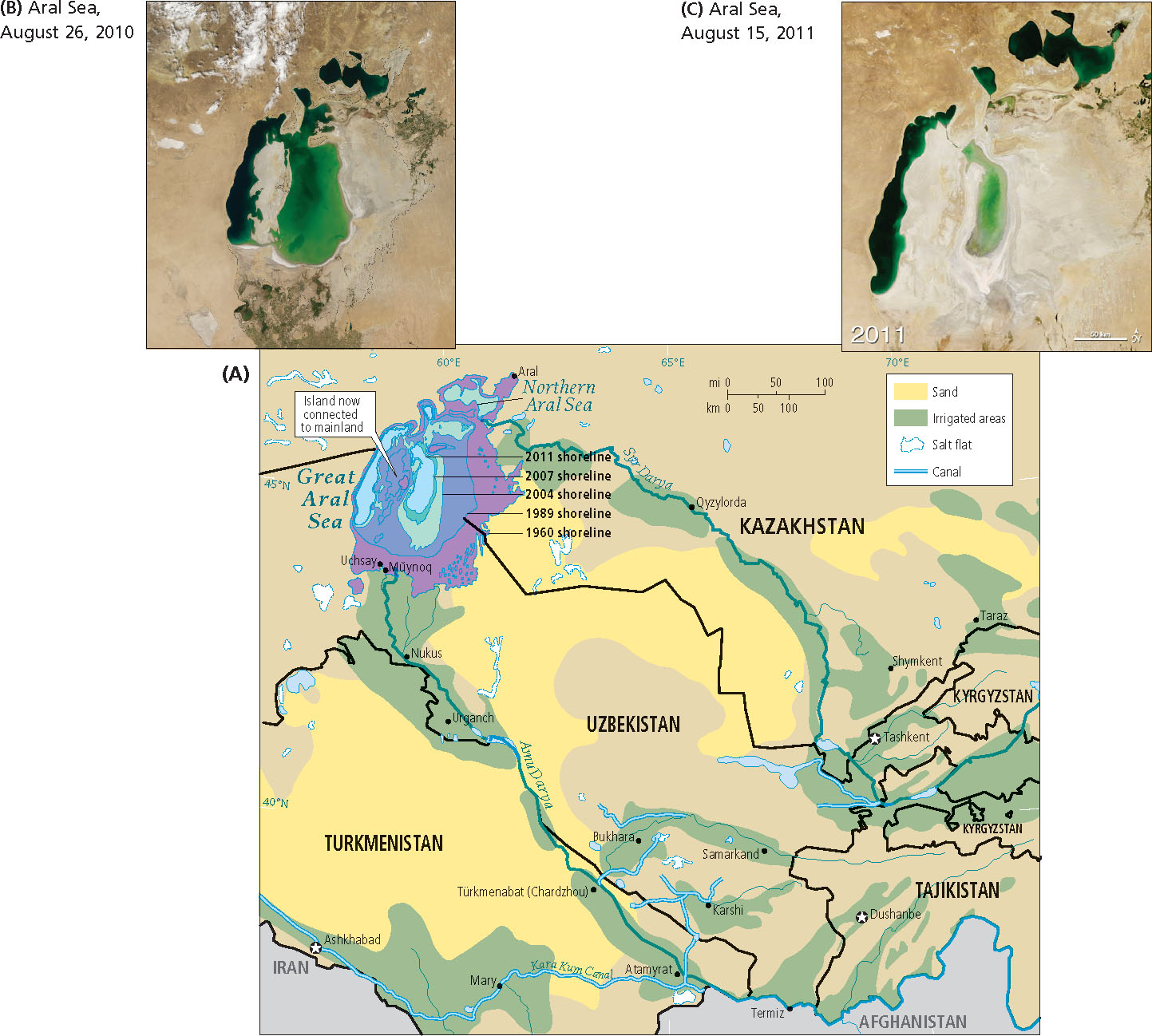

Rivers, Irrigation, and the Loss of the Aral Sea

To the south of Russia in the Central Asian states, glacially fed rivers have long served an irrigation role, supporting commercial cotton agriculture (see the discussion of the effects of global climate change on glaciers in Chapter 1, GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE. For millions of years, the landlocked Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake in the world, was fed by the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, which bring snowmelt and glacial melt from the mountains in Kyrgyzstan and other nearby countries. Water was first diverted from the two rivers in the 1960s when the Soviet leadership ordered its use to irrigate millions of acres of cotton in naturally arid Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. So much water was consumed by these projects that within a few years, the Aral Sea had shrunk measurably (Figure 5.7A). By the early 1980s, no water at all from the two rivers was reaching the Aral Sea, and by 2001, the sea had lost 75 percent of its volume and had shrunk into three smaller lakes. The region’s huge fishing industry, on which the entire USSR population depended for some 20 percent of their protein, died out due to increasing water salinity. Once-active port cities were marooned many kilometers from the water. The decline and disappearance of the Aral Sea has been described as the largest human-made ecological disaster in history.

The shrinkage of the Aral Sea has caused many human health problems. Winds that sweep across the newly exposed seabed pick up salt and chemical residues, creating poisonous dust storms. At the southern end of the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan, 69 percent of the people report chronic illnesses caused by air pollution, a lack of clean water, and underdeveloped sanitation.

Efforts to increase water flows to the Aral Sea have been hampered by politics because the now-independent countries of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan share the sea. Uzbekistan, in particular, wants to continue massive irrigation programs, which have made it the world’s seventh-largest cotton grower. Nevertheless, some restorative actions have been taken. Kazakhstan, which relies on oil more than cotton for income, built a dam in 2005 to keep fresh water in the northern Aral Sea. By the following year, the water had risen 10 feet, and the fish catch was improving. Kazakh fishers note that there is now more open public debate about what to do next regarding the Aral Sea. In the southern Aral Sea, however, water levels remain very low (see Figure 5.7B, C). In Uzbekistan, for instance, where 44 percent of the workforce is employed in agriculture, the limitation of irrigation has forced economic diversification, and cotton production now makes up just 11 percent of the country’s exports, far less than the 45 percent it represented in 1990.  107. DYING SEA MAKES COMEBACK

107. DYING SEA MAKES COMEBACK

Climate Change

Geographic Insight 2

Climate Change, Food, and Water: Food production systems and water resources are particularly threatened by climate change in parts of this region, yet the region remains the third-largest global producer of greenhouse gases.

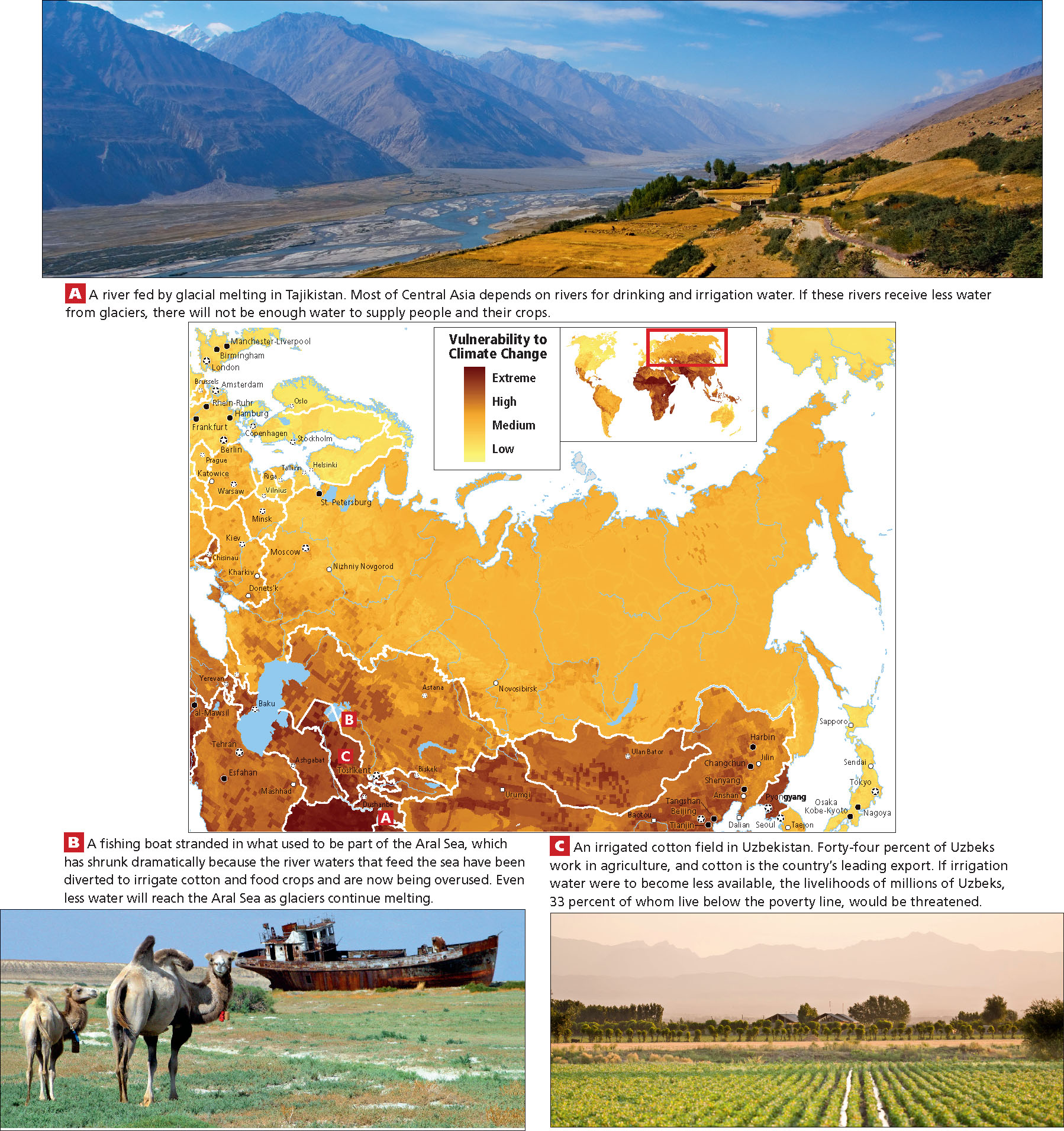

Climate change is an issue in this region for many reasons. While high levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases are produced here, Russia’s forests also play a major role in absorbing global CO2. Also, portions of the region have a medium level of vulnerability to the negative effects of a changing climate (shown on the map in Figure 5.8), but Central Asia, which is prone to drought and water scarcity, has high to extreme levels of vulnerability to climate change effects.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the vulnerability to climate change in Russia and the post-Soviet states, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Why would rivers like the one in this photo receive less water over the long term due to climate change?

Why would rivers like the one in this photo receive less water over the long term due to climate change?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What major resource did the Aral Sea once provide in abundance?

What major resource did the Aral Sea once provide in abundance?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Although Russia has reduced its CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions in recent years, it is still a major contributor of such emissions (see Figure 1.23). In fact, Russia has the third-highest rate of greenhouse gas emissions in the world. It is lagging in the use of energy-efficient technologies and many wasteful practices are common, such as burning off or “flaring” of natural gas that comes to the surface when oil wells are drilled. The results are higher greenhouse gas emissions per capita when compared to European countries; however, they are not as high as those in the United States. Russia has shown some willingness to limit its own emissions by, for example, signing international treaties, such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Copenhagen Accord, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Such treaties, however, use 1990 as a baseline for emissions. Russia’s compliance with international targets to reduce greenhouse emissions is largely an outcome of the country’s post-1990 economic decline after the end of communism. Lower levels of industrial output have meant lower emissions.

The dependence in Central Asia on irrigated agriculture using water from rivers that are fed by glaciers in the Pamirs and other mountains in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (see Figure 5.8), leaves the region vulnerable to global climate change. In recent decades, the glaciers have shrunk because of more extreme temperature ranges and decreases in rain and snowfall. If the glaciers have a decreased capacity to act as water-storage systems that supply melted ice flow to the rivers, the rivers may run dry during the summer, when irrigation is most needed for growing crops. Because most rain falls in the mountains in the winter and spring, Central Asia’s agricultural systems would either have to adapt to a spring growing season (winters are too cold), or farmers would have to store water for use in the summer. Either proposition demands complex and expensive changes on a massive scale.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The largest country in the world, Russia is nearly twice the size of the second-largest country, Canada. The region encompasses numerous landforms and associated climates.

The largest country in the world, Russia is nearly twice the size of the second-largest country, Canada. The region encompasses numerous landforms and associated climates. Geographic Insight 1Environment, Development, and Urbanization Urban and industrial pollution were ignored during Soviet times as cities expanded quickly to accommodate new industries. In some places, nuclear contamination is also a serious concern.

Geographic Insight 1Environment, Development, and Urbanization Urban and industrial pollution were ignored during Soviet times as cities expanded quickly to accommodate new industries. In some places, nuclear contamination is also a serious concern. Industries are attempting to become cleaner, but decades may pass before significant improvements are realized.

Industries are attempting to become cleaner, but decades may pass before significant improvements are realized. Global climate change is also a rising concern, with Russia a major contributor of greenhouse gases.

Global climate change is also a rising concern, with Russia a major contributor of greenhouse gases. Geographic Insight 2Climate Change, Food, and Water Central Asia is especially vulnerable to climate change, given its dependence on irrigated agriculture that uses water from rivers fed by glacial melt.

Geographic Insight 2Climate Change, Food, and Water Central Asia is especially vulnerable to climate change, given its dependence on irrigated agriculture that uses water from rivers fed by glacial melt.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Better Times Ahead?

While environmental pollution remains serious throughout this region, there may be reasons for optimism in the post-Soviet era. New patterns of economic development could bring better living standards, especially for urban residents who could pressure governments for higher environmental standards. Moreover, while freedom of expression and the press are still limited throughout the region, they are at least better than they were in Soviet times. This opens up the opportunity to make use of the media to expose the worst cases of pollution and environmental negligence. For example, in Sochi, Russia, a Black Sea resort town long cherished for its natural amenities, numerous environmental protests about the high levels of urban pollution have gained global attention in recent years. Such attention will probably increase, as Sochi will host the 2014 Winter Olympics. Similarly, much of the information presented above has come to light as a result of greater press freedom since the collapse of the Soviet Union.