Economic and Political Issues

oligarchs in Russia, those who acquired great wealth during the privatization of Russia’s resources and who use that wealth to exercise power

Oil and Gas Development: Fueling Globalization

Geographic Insight 3

Globalization and Development: Since the fall of the Soviet Union, economic reforms and globalization have changed patterns of development in this region. Many Communist-era industries closed, and as jobs were lost and public assets sold to wealthy oligarchs, wealth disparity increased. The region is now dependent on its role as a leading global exporter of energy resources.

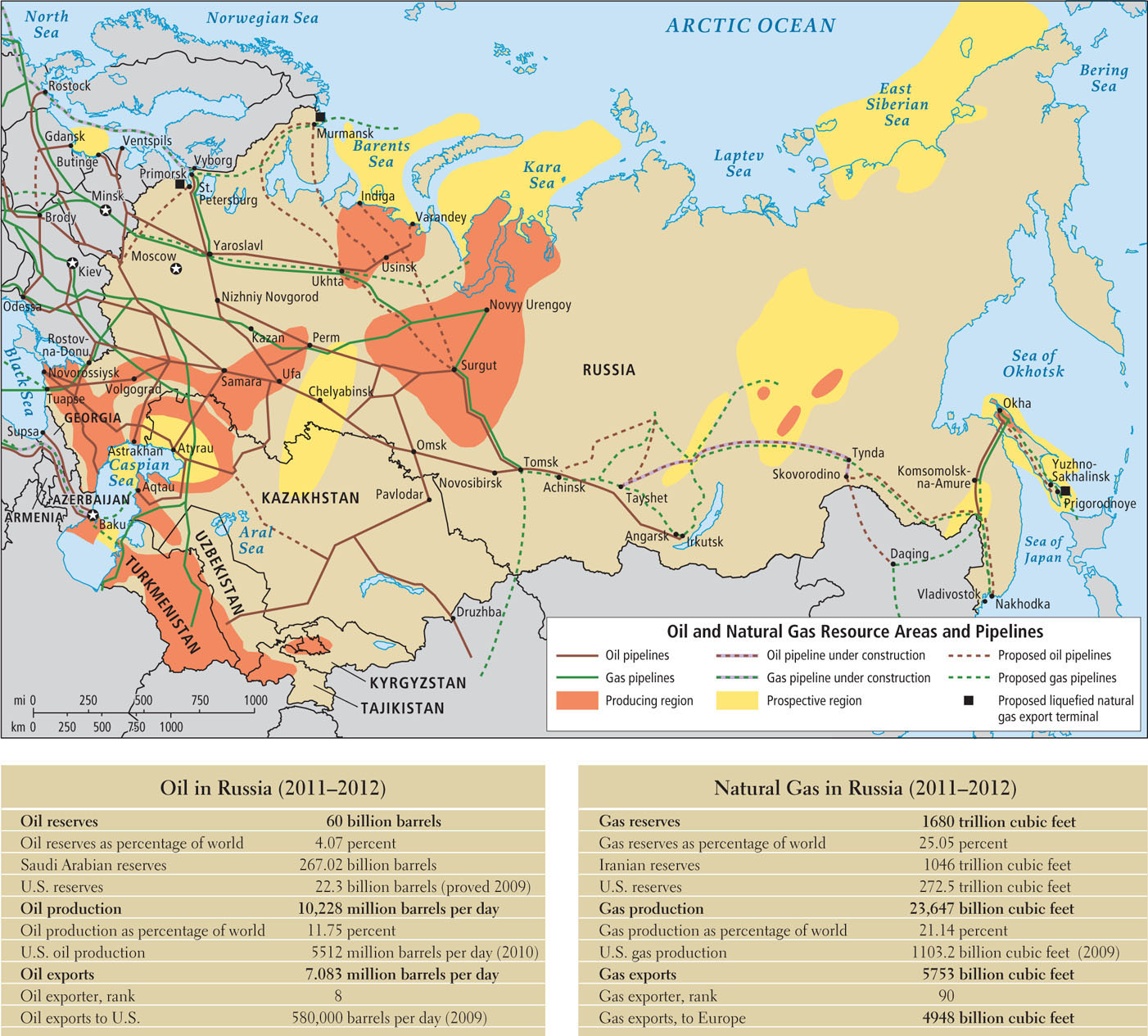

Natural gas and crude oil have emerged as the region’s most lucrative exports, introducing a new wave of globalization and fossil fuel–dependent economic development. While control of Russia’s oil and gas resources still lies largely in the hands of the Russian government, the struggle to control Central Asia’s oil and gas resources involves many multinational corporations and countries and could be a source of conflict for years to come (Figure 5.14).

By the year 2000, after an initial decade of economic instability, rising revenues from oil and gas began to finance Russia’s economic recovery. In response, Russia’s central government tightened control over the entire oil and gas sector. Today, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, and taxes on energy companies fund more than half of the federal budget. While this does guarantee that at least some of the revenues from the new fossil fuel–based industries benefit Russia’s population, the remaining profits are concentrated in the hands of a few oligarchs.

Gazprom in Russia, the state-owned energy company; it is the largest gas entity in the world

Meanwhile, Central Asia has yet to find stability because a tug-of-war has evolved between Russia and foreign multinational energy corporations over the right to develop, transport, and sell Central Asian oil and gas resources. The new Central Asian states do not have the capital to develop the resources themselves, yet individuals and special interests in the Central Asian countries are reaping enormous financial rewards from selling to outsiders the rights to exploit oil and gas.

The pipeline routes are the key source of contention (see Figure 5.14). Because the region is landlocked, the only way to get oil and gas to world markets is via pipelines. The capacity and geography of the pipeline network determines how that takes place. Russia, the United States, the European Union, Turkey, China, and India have all developed or proposed various routes. A 1900-mile (3000-km) pipeline from the Caspian Sea to China serves the growing demand for energy in China. The United States maintains a military presence to protect its interests in countries such as Georgia and Uzbekistan, both of which, along with Turkey, have pipelines to Europe. Russia has built pipelines that traverse its own territory and reach into Europe. Each of these parties has made numerous efforts to encourage Central Asian countries to use their pipelines instead of those of their competitors.

Russia’s Relations with the Global Economy

Both the European Union and the United States want to ensure that Russia’s oil and gas wealth does not finance a return to the hostile relations of the Cold War. For this reason, Russia was invited to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Group of Eight (G8), an organization of eight affluent countries with large economies.

Looking to form an economic counterweight to the United States and the European Union, Russia has recently been meeting with Brazil, India, and China to form a trade consortium known as BRIC. All four countries have had spectacular economic growth over the last decade, though Russia’s economy is arguably the slowest growing and least diverse in the group due to its dependence on fossil fuel exports.

Economic Reforms in the Post-Soviet Era

Transitioning from one economic system to another is a major undertaking for any society. Not only do such changes take a long time to implement fully, they also disrupt existing geographic patterns of production and affect the livelihood of many people, both in positive and negative ways. The transition from communism to a market economy in the post-Soviet states turned out to be more complex and problematic than many had anticipated.

Reforming the Command Economy

perestroika literally, “restructuring”; the restructuring of the Soviet economic system that was done in the late 1980s in an attempt to revitalize the economy

glasnost literally, “openness”; the policies instituted in the late 1980s under Mikhail Gorbachev that encouraged greater transparency and openness in the workings of all levels of Soviet governments

Privatization and the Lifting of Price Controls

privatization the sale of industries that were formerly owned and operated by the government to private companies or individuals

Unfortunately, shock therapy came at a steep cost for many Russians. A major part of the reforms was the abandonment of government price controls that once kept goods affordable to all. Instead, private business owners now determine prices. The lifting of price controls led to inflation and skyrocketing prices in the 1990s for the many goods that were in high demand but also in short supply. While a few people became rich, many people lost much of their savings because of inflation and could barely pay for basic necessities such as food. Eventually, as opportunities opened and competition developed, the supply of goods increased and prices fell. But in the interim, many people suffered. The Russian state also lost tax revenue and only a bailout from the International Monetary Fund saved the country from bankruptcy.

Unemployment and the Loss of Social Services

Since becoming privatized, most formerly state-owned industries have cut many jobs in an attempt to compete against more-efficient foreign companies. Losing a job is especially devastating in a former Soviet country because one also loses the subsidized housing, health care, and other social services that were often provided along with the job. The new companies that have emerged rarely offer full benefits to employees. There is little job security because most small private firms appear quickly and often fail. Discrimination is also a problem, given the absence of equal opportunity laws. Job ads often contain wording such as “only attractive, skilled people under 30 need apply.”

underemployment the condition in which people are working too few hours to make a decent living or are highly trained but working at menial jobs

The Difficult Legacies of Soviet Regional Development Schemes

One of the reasons that so many state-owned firms have had to cut jobs is that they were components of largely failed regional development schemes. Numerous huge industrial areas were located in far-flung eastern portions of the Soviet Union, in large part to facilitate the political control of these areas. These projects were always held back by the vast distances and challenging physical geography that separated them from the main population centers in the west of the region. Because the region’s rivers run mainly north to south, there was a need for land transportation systems, such as railroads and highways, that ran east to west. These proved exceedingly expensive to build and maintain, and many have fallen into disrepair in the post-Soviet era. Only one poorly paved road, and only one main rail line—the Trans-Siberian Railroad (Figure 5.15)—runs the full east–west length, connecting Moscow with Vladivostok, the main port city on the Russian Pacific coast.

By contrast, the road and rail network is fairly dense within western Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, with Moscow as the main hub. This has had the effect of concentrating new economic development in these western areas. Hence, the industrial cities of eastern Russia have lost many jobs and their populations are shrinking because the Russian government is no longer interested in subsidizing regional economic development in the east.

Institutionalized Corruption

The cost of doing business in Russia is also affected by a high level of corruption. In 2010, the organization Transparency International rated Russia the most corrupt of all major countries in the world. While Russia today is vastly different from the old Soviet Union, many officials have not made the transition to a more democratic mindset. Civil servants and the police are prone to being corrupted. They often expect businesses to offer bribes to receive licenses and to avoid other regulatory hurdles. This affects large corporations and small entrepreneurs alike. Even those who make it through the labyrinth of setting up a business must then face protection racketeers, as organized crime has become a fact of life during the post-Communist era. These crime syndicates have also developed international networks through which they control illicit activities abroad, especially in Europe.

The Growing Informal Economy

A large share of the economic activity in the region takes place in the informal sector. To some extent, the new informal economy is an extension of the old one that flourished under communism. The black market of that time was based on currency exchange and the sale of hard-to-find luxuries. In the 1970s, for example, savvy Western tourists could enjoy a vacation on the Black Sea paid for by a pair or two of smuggled Levi’s blue jeans and some Swiss chocolate bars. Today, many people who have lost stable jobs due to privatization now depend on the informal economy for their livelihood.

Workers in the informal economy tend to be very young unskilled adults, retirees on miniscule pensions, and those with only a low level of education. The majority of these workers operate out of their homes by selling cooked foods, vodka made in their bathtubs, clothing, or electronics that have been smuggled into the country. The World Bank has estimated that the informal sector makes up about 40 percent of the Russian economy. In the Caucasian countries, the number is as high as 50 to 60 percent. Such large percentages indicate that people may actually be better off financially than official GDP per capita figures suggest.

Despite the fact that the informal economy helps people survive, it is not popular with governments. Unregistered enterprises do not pay business and sales taxes and usually are so underfinanced that they tend not to grow into job-creating formal sector businesses. In many cases, informal businesspeople must pay protection money to local gangsters (the so-called Mafia tax) to keep from being reported to the authorities.

VIGNETTE

Natasha is an engineer in Moscow. She has managed to keep her job and the benefits it carries, but in order to better provide for her family, she sells secondhand clothes in a street bazaar on the weekends. “Everyone is learning the ropes of this capitalism business,” she laughs. “But it can get to be a heavy load. I’ve never worked so hard before!” Asked about her customers, Natasha says, “Many are former officials and high-level bureaucrats who just can’t afford the basics for their families any longer.” Some are older retired people whose pensions are so low that they resort to begging on Moscow’s elegant shopping streets close to the parked Rolls-Royces of Moscow’s rich. These often highly educated and only recently poor people buy used sweaters from Natasha and eat in nearby soup kitchens. [Source: This composite story is based on work by Alessandra Stanley, David Remnick, David Lempert, and Gregory Feifer.]

Food Production in the Post-Soviet Era

Across most of the region, agriculture is precarious at best, either hampered by a short growing season and boggy soils or requiring expensive inputs of labor, water, and fertilizer. Because of Russia’s harsh climates and rugged landforms, only 10 percent of its vast expanse is suitable for agriculture. The Caucasus mountain zones are some of the only areas in the region where rainfall adequate for agriculture coincides with a relatively warm climate and long growing seasons. Together with Ukraine and European Russia, this area is the agricultural backbone of the region (Figure 5.16). The best soils are in an area stretching from Moscow south toward the Black and Caspian seas, and extending west to include much of Ukraine and Moldova. In Central Asia, irrigated agriculture is extensive, especially where long growing seasons support cotton, fruit, and vegetables.

Changing Agricultural Production

During the 1990s, agriculture went into a general decline across the entire region. In most of the former Soviet Union, yields dropped by 30 to 40 percent compared to previous production levels. This was due mostly to the collapse of the subsidies and internal trade arrangements of the Soviet Union. Many large and highly mechanized collective farms suddenly found themselves without access to equipment, fuel, or fertilizers. Since that time, agricultural output has rebounded but even today remains below Soviet levels. Russia’s commercial agricultural sector is still characterized by many large and inefficient farms. However, if global food prices are high and agricultural productivity increases, the most important farming areas might be able to expand grain production and turn the region into an viable food exporter. Meanwhile, Russians are heavily dependent on “homegrown” food—small household plots and gardens that produce 47 percent of total agricultural output.

In Central Asia, agriculture has been reorganized with less emphasis on collective farming of export crops and more on smaller, food-producing family farms. Grain and livestock farming (for meat, eggs, and wool) are increasing. Production levels per acre and per worker also are increasing. China, through the Asian Development Bank, has provided assistance in reducing the use of agricultural chemicals, which were used extensively during Soviet times.

Farmers in Georgia, blessed with warm temperatures and abundant moisture from the Black and Caspian seas, can grow citrus fruits and even bananas; they do so primarily on family, not collective, farms. Before 1991, most of the Soviet Union’s citrus and tea came from Georgia, as did most of its grapes and wine. Georgia still exports some food to Russia, but because of political tensions between the two countries, Georgia is increasing the amount of food and wine it sells to Europe and other markets outside this region.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development Patterns of development changed after 1991 with the switch to a market economy. As state-owned firms closed or were sold to private parties, jobs were lost and wealth disparities increased drastically. Crude oil and natural gas emerged as the region’s most lucrative exports, introducing a new wave of globalization and fossil fuel–dependent economic development.

Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development Patterns of development changed after 1991 with the switch to a market economy. As state-owned firms closed or were sold to private parties, jobs were lost and wealth disparities increased drastically. Crude oil and natural gas emerged as the region’s most lucrative exports, introducing a new wave of globalization and fossil fuel–dependent economic development. The Soviet centrally planned economy was less efficient than market economies in allocating resources. A legacy of Soviet central planning is the location of huge industrial projects in the farthest reaches of Soviet territory. Many of these projects are now in decline.

The Soviet centrally planned economy was less efficient than market economies in allocating resources. A legacy of Soviet central planning is the location of huge industrial projects in the farthest reaches of Soviet territory. Many of these projects are now in decline. The benefits of economic reforms in the post-Soviet era have been dampened by widespread corruption, organized crime, lower incomes for many, and the loss of social services.

The benefits of economic reforms in the post-Soviet era have been dampened by widespread corruption, organized crime, lower incomes for many, and the loss of social services. Across most of the region, agriculture is precarious, either hampered by a short growing season and boggy soils or requiring expensive inputs of labor, water, and fertilizer. European Russia and Ukraine is the region’s main breadbasket.

Across most of the region, agriculture is precarious, either hampered by a short growing season and boggy soils or requiring expensive inputs of labor, water, and fertilizer. European Russia and Ukraine is the region’s main breadbasket.

Democratization in the Post-Soviet Years

Geographic Insight 4

Power and Politics: Obstacles to democratization include a long history of authoritarian regimes and the popular desire to implement change rapidly, combined with the lack of mechanisms for public participation in the political process.

Democratization in this region has not proceeded as quickly as has the introduction of a market economy. While several countries have held elections, many forms of authoritarian control remain. Elected representative bodies often act as rubber stamps for very strong presidents and exercise only limited influence on policy.

In Russia, Vladimir Putin, a former high official in the KGB (Russia’s intelligence agency during the Cold War, now known as the Federal Security Service, or FSB), was elected president in 2000 and has been the country’s de facto leader as either president or prime minister ever since. During this time, he has exercised tight control over political and economic policy and consolidated political power in Moscow. He has been popular for bringing relative peace and prosperity and for restoring Russia’s image of itself as a world power, despite disallowing meaningful democratic reforms at the local, state, and national levels, and extending government control over the press and the media. Ostensibly, criticism of the government is now allowed; but behind the scenes, critics fear retribution from the securocrats or siloviki (former FSB functionaries loyal to Putin) who control many governing institutions. Political analyst Olga Kryshtanovskaya found that in 2006, 77 percent of the people in top government positions had backgrounds in security agencies.

117. PUTIN CONFIRMATION

117. PUTIN CONFIRMATION

123. NEW RUSSIAN LEADER

123. NEW RUSSIAN LEADER

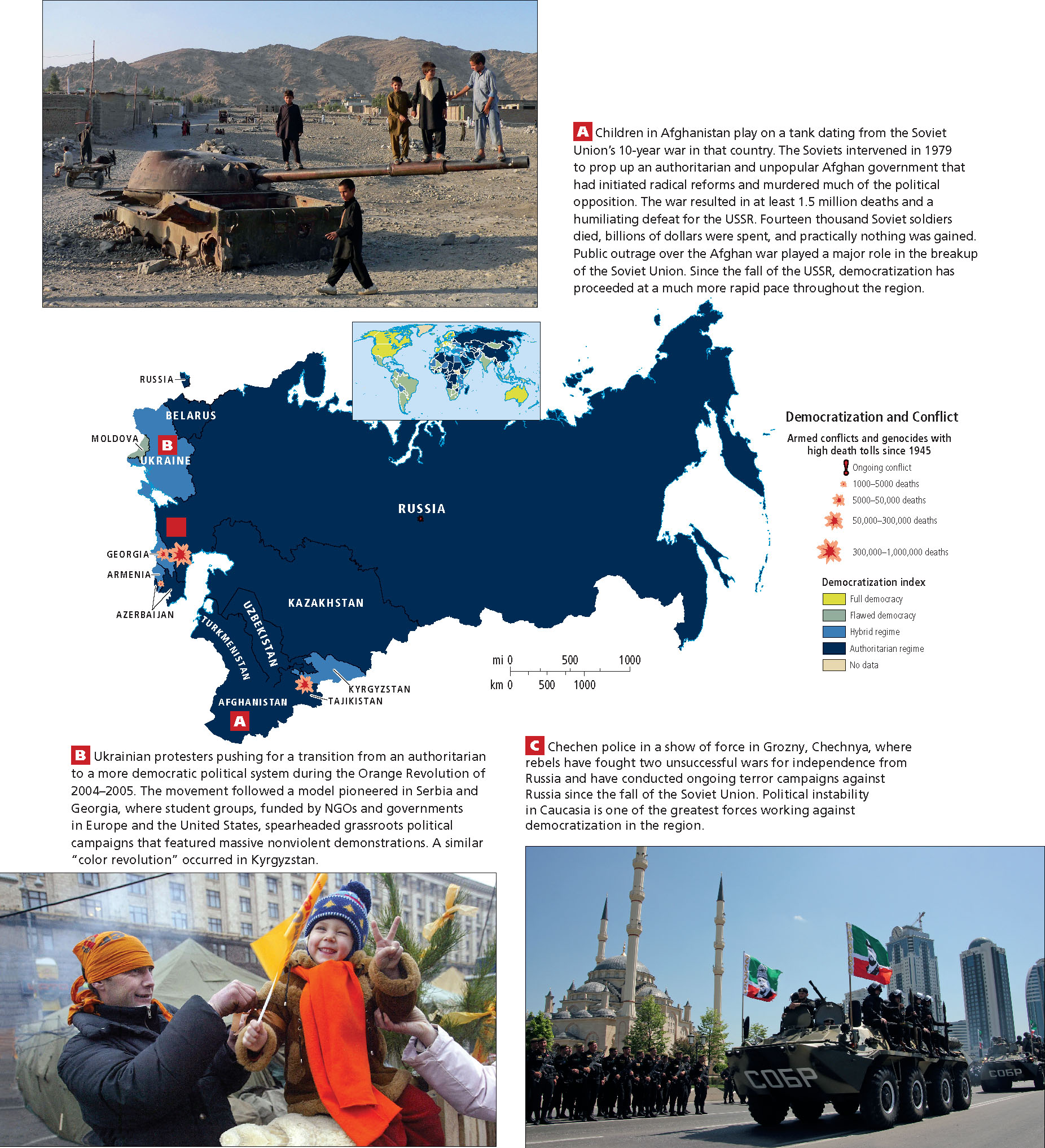

Elsewhere in the region, progress toward true democracy is similarly limited. In Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, the Caucasian republics (including Chechnya, discussed), and Central Asia, authoritarian leaders are still the most common and are unaccustomed to criticism or to sharing power (see the map in Figure 5.17). Elections often involve systematically intimidating voters and arresting the political opposition.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in Russia and the post-Soviet states, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

How did the USSR's war in Afghanistan ultimately contribute to democratization in the Soviet Union?

How did the USSR's war in Afghanistan ultimately contribute to democratization in the Soviet Union?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Who funded the color revolutions?

Who funded the color revolutions?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How does Russia's unwillingness to let Chechnya secede relate to fossil fuel resources?

How does Russia's unwillingness to let Chechnya secede relate to fossil fuel resources?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The Color Revolutions and Democracy

In a few of the post-Soviet states, there have been a number of relatively peaceful transitions to somewhat greater democracy—the so-called color revolutions, including the Rose Revolution in Georgia (2003–2004), the Orange Revolution in Ukraine (January 2005; see Figure 5.17B), and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan (April 2005).

The democracy movements were named the “color revolutions” because they were led by coalitions of educated young adults who rallied under various symbolic colors meant to unite them despite differences. Funded largely by foreign NGOs and governments, including the United States, that wanted to hasten democratization, it appeared for a time that these movements would result in significant reforms. However, while elections have taken place, and some freedom of expression is tolerated, many forms of authoritarian control and practices that disrupt democratic procedures remain.

In Ukraine, which is now one of the more democratized countries of this region, the Orange Revolution occurred during the presidential elections of 2004. A candidate who favored closer ties with Russia, Viktor Yanukovych, won the election, but the results were so obviously rigged by the government that widespread protests went on for months. The protests, combined with international pressure, resulted in a new vote in which Viktor Yushchenko, who favored closer ties with the European Union and Ukrainian membership in NATO, won. In subsequent elections, however, the pro-Russian Yanukovych has returned to power.

Ukraine today is divided in terms of its geographic orientation. Areas to the west, which border Central Europe, tend to favor closer ties with Europe, while areas to the east, where many of Ukraine’s Russian-speaking minority reside, lean toward Russia. The 2011 jailing and sentencing to 7 years of the Orange Revolution leader Yulia Tymoshenko, who is one of the region’s few prominent female politicians, indicates that Ukraine’s progress toward democracy is in jeopardy.

Cultural Diversity and Democracy

Russia’s long history of expansion into neighboring lands has left it with an exceptionally complex internal political geography. As the Russian czars and then the Soviets pushed the borders of Russia eastward toward the Pacific Ocean over the past 500 years, they conquered a number of non-Russian areas. Russians are now the main inhabitants of many of those areas. Other territories have been designated semiautonomous internal republics (Figure 5.18), and they have significant ethnic minority populations that are descended from indigenous people or trace their origins to long-ago migrations from Germany, Turkey, or Persia.

Russification the czarist and Soviet policy of encouraging ethnic Russians to settle in non-Russian areas as a way to assert political control

Shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, several internal republics demanded greater autonomy, and two of them, Tatarstan and Chechnya, declared outright independence. Tatarstan has since been placated with greater economic and political autonomy. However, Chechnya’s stronger resistance to Moscow’s authority has led to the worst bloodshed of the post-Soviet era and raised many doubts about Russia’s commitment to human rights.

Chechnya, located on the fertile northern flanks of the Caucasus Mountains, is home to 800,000 people (see the inset map in Figure 5.18). Partially in response to Russian oppression, the Chechens converted from Orthodox Christianity to the Sunni branch of Islam in the 1700s. Since then, Islam has served as an important symbol of Chechen identity and as an emblem of resistance to the Orthodox Christian Russians, who annexed Chechnya in the nineteenth century.

In 1942, during World War II, as the Germans continued to fight in Russia, a group of Chechen rebels simultaneously waged a guerilla war against the Soviets. Near the end of the war, Stalin exacted his revenge by deporting the majority of the Chechen population (as many as 500,000 people) to Kazakhstan and Siberia. Here they were held in concentration camps, and many died of starvation. The Chechens were finally allowed to return to their villages in 1957, but a heavy propaganda campaign portrayed them as traitors to Russia, a designation that greatly affected daily life.

In 1991, as the Soviet Union was dissolving, Chechnya declared itself an independent state. Russia saw this as a dangerous precedent that could spark similar demands by other cultural enclaves throughout its territory. Russia also wished to retain the agricultural and oil resources of the Caucasus; it had planned to build pipelines across Chechnya to move oil and gas to Europe from Central Asia. Russia responded to acts of terrorism by Chechen guerrillas with bombing raids and other military operations that killed tens of thousands and created 250,000 refugees. Presently, most Chechen guerillas have given up, most Russian combat troops have been pulled out of Chechnya, and Russia has begun making substantial investments in rebuilding the capital city of Grozny. While this shift is a welcome change, some Chechen rebels have continued their struggle by carrying out brutal terrorist attacks, many of which now take place in Moscow and other areas outside Chechnya, such as in Boston during the 2013 marathon. Chechnya remains highly militarized (see Figure 5.17C), and the ongoing conflict there continues to raise doubts about Russia’s ability to peacefully address internal political dissent.  116. CHECHNYA HANGS ON TO UNEASY PEACE

116. CHECHNYA HANGS ON TO UNEASY PEACE

Just south of Chechnya, conflicts between Russia and Georgia over the ethnic republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia have worsened in the post-Soviet era. Both republics became part of Georgia at the behest of Joseph Stalin (a native Georgian). He then moved Georgians and Russians into Ossetia and Abkhazia so that the native people became a minority in their own place. More recently, Russia has strategically supported the ethnic Ossetian and Abkhazian populations’ agitation for secession from Georgia, even granting Russian citizenship to between 60 to 70 percent of the non-Georgian population. Russia may have done this in retaliation for Georgia’s increasingly close relations with the United States and the European Union, as evidenced by its candidacy for NATO membership. A pipeline that links the oil fields of Azerbaijan with the Black Sea via Georgia is another source of contention (see Figure 5.14). The Black Sea route is important because it is an expedient way to ship oil to world markets, as the Black Sea connects to the Mediterranean Sea and, ultimately, to the Atlantic Ocean. Russia would like to enhance its control over the oil resources of the Caspian Sea region by routing pipelines through Russian-controlled territory.

Although in 2008, Georgia’s military, attempting to gain control over rebelling parts of South Ossetia, engaged with the Russian army on Russian territory, that conflict ended without clear resolution. It is not clear at this time whether Abkhazia and South Ossetia will break away and become independent countries, become provinces within the Russian Federation, or be satisfied by offers of greater autonomy within Georgia’s federal structure (see Figure 5.32).

The Media and Political Reform

During the Soviet era, all communication media were under government control. There was no free press, and public criticism of the government was a punishable offense. However, toward the end of the Soviet era, many journalists risked retribution for criticizing public officials and policies. Between 1991 and the early 2000s, the communications industry was a center of privatization, and several media tycoons emerged to challenge the authorities. Privately owned newspapers and television stations regularly criticized the policies of various leaders of Russia and the other states. It appeared that a free press was developing.

In Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, however, the most outspoken newspapers and TV stations in Russia were shut down. Since then, critical analysis of the government has become rare throughout Russia. Journalists openly critical of government policies have been treated to various forms of punishment: censorship, exile, or violence. Since 2000, approximately 200 journalists have been killed under violent or unclear circumstances.

Corruption and Organized Crime

Any potential benefits of political and economic reforms in the post-Soviet era have been dampened by widespread corruption and the growth of organized crime. Many oligarchs became closely connected to the Russian Mafia, a highly organized criminal network dominated by former KGB and military personnel who control the thugs on the streets. The Russian Mafia extended its influence into nearly every corner of the post-Soviet economy, especially in illegal activities and the arms trade.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 4Power and Politics While several countries have held elections, many forms of authoritarian control remain. Elected representative bodies often act as rubber stamps for very strong presidents and exercise only limited influence on policy.

Geographic Insight 4Power and Politics While several countries have held elections, many forms of authoritarian control remain. Elected representative bodies often act as rubber stamps for very strong presidents and exercise only limited influence on policy. Since World War II, most conflicts in this region have been in Caucasia and Central Asia, mainly just before or shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union. In the years after the breakup, pro-democracy movements have emerged in several countries, where they hold the promise of bringing political change without violent conflict. However, their long-term effectiveness remains unclear.

Since World War II, most conflicts in this region have been in Caucasia and Central Asia, mainly just before or shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union. In the years after the breakup, pro-democracy movements have emerged in several countries, where they hold the promise of bringing political change without violent conflict. However, their long-term effectiveness remains unclear. There continue to be limitations on the free press and related media across the region.

There continue to be limitations on the free press and related media across the region. The potential benefits of political and economic reforms in the post-Soviet era have been dampened by official corruption and the growth of organized crime.

The potential benefits of political and economic reforms in the post-Soviet era have been dampened by official corruption and the growth of organized crime.