Sociocultural Issues

When the winds of change began to blow through the Soviet Union in the 1980s, few anticipated the rapidity and depth of the transformations or the social instability that resulted. On the one hand, new freedoms have encouraged self-expression, individual initiative, and cultural and religious revival (Figure 5.19); on the other hand, the post-Soviet era has brought very hard times to many as their jobs and the social safety net have been obliterated.

Population Patterns

Geographic Insight 5

Population: Populations are shrinking in many parts of this region. This is a function of a continuously high level of participation by women in the workforce and overall poor living and housing standards.

This region shares some of the same population characteristics as the United States and Europe—low birth rates and an aging population—both usual features of wealthy and developed societies. But in Russia and the post-Soviet states, low birth rates are more extreme and are coupled with high mortality rates for middle-aged males, leading to a relatively low life expectancy. Several circumstances contribute to this situation.

Population Distribution and Urbanization

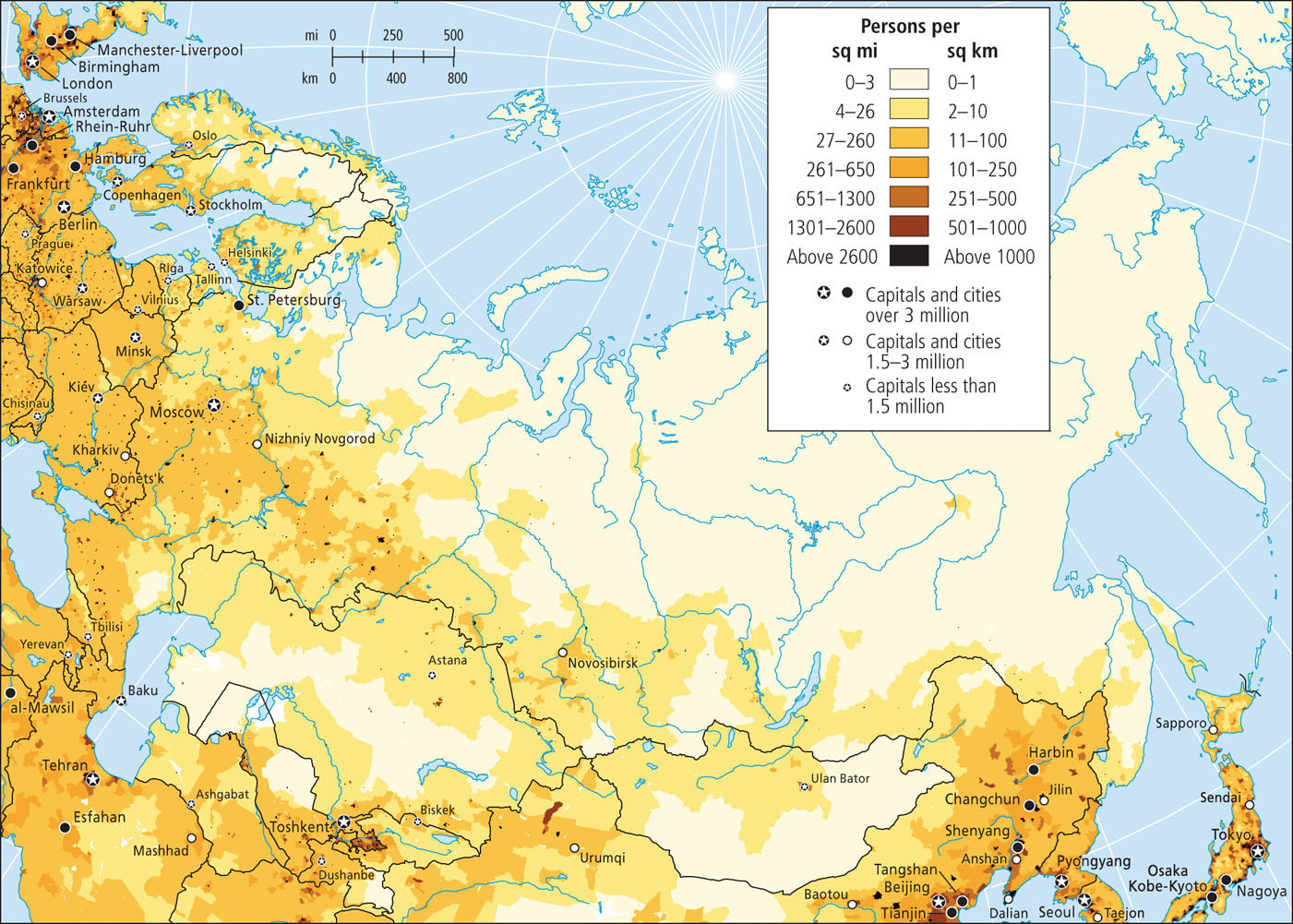

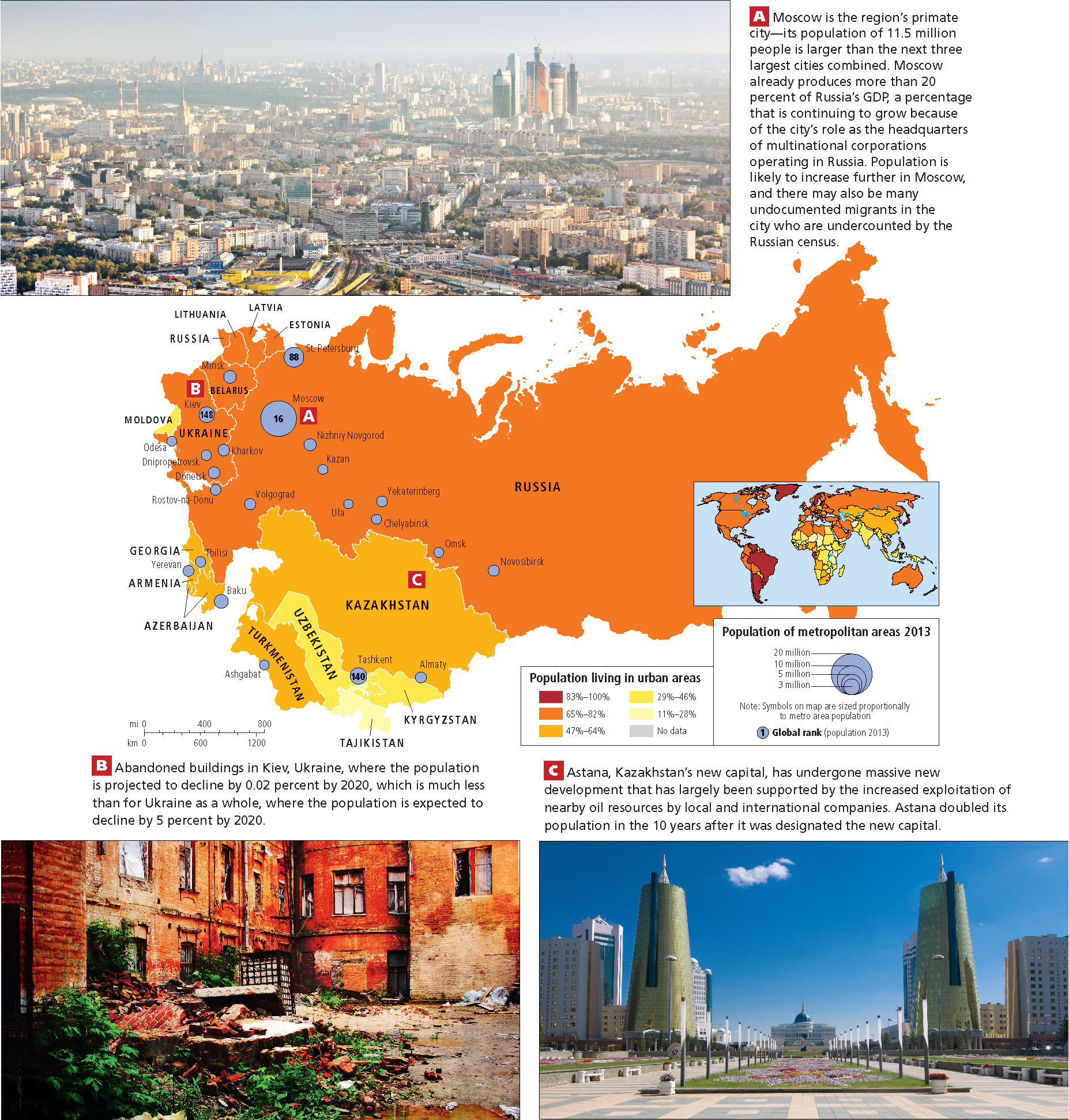

The region of Russia and the post-Soviet states is one of the largest on Earth but is the least densely populated, with only about 282 million people. A broad area of moderately dense population forms an irregular triangle that stretches from Ukraine on the Black Sea north to St. Petersburg on the Baltic Sea and east to Novosibirsk, the largest city in Siberia. In this triangle, settlement is highly urbanized, but the cities are widely dispersed. The capital city of Moscow, with 11.5 million people, is a primate city in Russia, as are all other capital cities of the nations in this region (Figure 5.20).

Beyond Novosibirsk on the West Siberian Plain, settlement follows an irregular and sparse pattern of industrial and mining development in widely spaced cities, stretching east across Siberia. These economic activities and the cities they support are linked primarily to the route of the Trans-Siberian Railroad (see Figure 5.15). Nearly 90 percent of Siberia’s people are concentrated in a few relatively large urban areas. The costs of maintaining these settlements in this remote and harsh environment are considerable. The low concentration of people is affected by the great distance from the main areas of economic activity and markets in European Russia. One telling statistic is that the population density in Russia’s Far East is 140 times lower than it is just across the border in northeastern China, which has a similar physical environment.

Caucasia the mountainous region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea

VIGNETTE

Yernar Zharkeshov is a 24-year-old university-educated young man who is moving back home to Kazakhstan after having spent time in Britain and Singapore. He is seeking new opportunities in his homeland, which are increasing because of extensive oil exports. The natural choice for him is Astana, a city that was designated the capital of Kazakhstan in 1997. Yernar quickly found a job as a government economist—and he is just one of thousands of young people who have migrated to the growing capital.

The idea of Astana came from Nursultan Nazarbayev, who has been president of Kazakhstan since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Without much public debate, he moved the capital from Almaty in the south to the remote and sparsely populated steppe in the north, which is known for its harsh climate. Here he realized his vision for a grand and impressive new capital built more or less from scratch. Astana is meant to symbolize a new, forward-looking Kazakhstan. Such energy-driven urbanization makes Astana similar to Persian Gulf cities such as Dubai and Doha. Another appropriate comparison is to the decision by the Russian czar Peter the Great to build a new imposing imperial capital—St. Petersburg—during the eighteenth century. Nazarbayev spared no expenses when building Astana; the city is full of stunning buildings, either designed by world-renowned architects or by Nazarbayev himself (see Figure 5.22).

Like many other migrants to Astana, Yernar Zharkeshov is an ethnic Kazakh. President Nazarbayev’s unspoken motive for moving the capital is to consolidate the country’s northern territories, which are currently dominated by ethnic Russians. The presence of these Russians is the result of the practice of Russification during the days of the Soviet Union. Astana has been designed to promote the opposite, or “Kazakhification” of the country’s north. [Source: National Geographic. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Post-Communist lifestyles in urban centers of Russia and the post-Soviet states are very different from the traditional lifestyles of the people of this region, who used to be more dependent on what nature could provide (Figure 5.21). Urban life for most remains shaped by the Communist-era legacies of central planning. Giant apartment blocks, designed by bureaucrats and built for industrial workers, dominate most cities, especially on the fringes of pre-Soviet urban cores. In the growing cities, such as Moscow and St. Petersburg, the housing shortages of the Soviet era have not abated since 1991. Cramped, drab apartments badly in need of repair, with shared kitchens and bathrooms, are common. At the community scale, inadequate sewage, garbage, and industrial waste management pose serious long-term health and environmental threats.

In Moscow, housing shortages are irregular but particularly severe because the city, as the focus of new investment in the region, has grown rapidly since 1991. Due to high demand, the cost of housing has increased so dramatically that Moscow has one of the highest costs of living in the world. Other cities face housing shortages, even as their populations shrink, because of general deterioration and the absence of funds for maintenance (Figure 5.22B). Shortages are also exacerbated by the ability of wealthy people to buy up multiple apartments and refurbish them into one luxurious dwelling. A few cities that are still growing have attracted both government and private investment to increase the housing stock.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in Russia and the post-Soviet states, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Why is Moscow growing so rapidly?

Why is Moscow growing so rapidly?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What larger-scale population trend does Ukraine's decline relate to?

What larger-scale population trend does Ukraine's decline relate to?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is responsible for the growth of Astana?

What is responsible for the growth of Astana?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Shrinking Populations

With high death rates and low birth rates, this region is undergoing a unique, late-stage variant of the demographic transition. In all but the Caucasian and Central Asian states, populations are shrinking faster than in any other world region. During the Soviet era, the increase in women’s opportunities to become educated and work outside the home curtailed population growth. Severe housing shortages were an additional disincentive to having children, and many families chose to have only one or two children. Free health care and adequate retirement pensions also helped lower incentives for large families. During the last years of the Soviet Union, the population was already shrinking, but this trend accelerated during the economic crisis brought on by the breakup of the USSR. Since then, Russia’s population has shrunk more than 5 percent, to 143 million. The United Nations predicts that Russia will drop to just 126 million people by 2050. Populations are also shrinking in Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine. Rural areas have been particularly affected. The Russian geographer Tatyana Nefedova has calculated that areas located more than 20 to 25 miles (35 to 40 kilometers) away from large cities, areas that she calls “Russia’s black holes,” are increasingly more deserted, with only the elderly remaining. Even in Central Asia and the Caucasian states, where higher birth rates should be resulting in robust growth, countries are still losing population because of emigration. Here, traditional rural lifestyles are often not economically viable anymore (see Figure 5.20). Many people migrate to Russia to find work. Russia’s population decline would actually be larger than it already is if not for this stream of immigrants.

Surveys suggest that in the parts of this region that have low birth rates, people are now choosing to have fewer children primarily out of concern over gloomy economic prospects for the near future and also out of the desire to make money and have fun. Russia is attempting to reverse population loss by paying couples to raise more children and by attracting back Russians and their dependents who live abroad. In 2007 and 2008, Russia spent $300 million to send emissaries to the far corners of the Earth (Brazil, Egypt, Germany, and all the post-Soviet states) to lure “returnees.” Only 10,300 were recruited.

In addition to negative birth and migration rates, much of the reason for the population decline is the declining life expectancy. In Russia, for example, between 1987 and 1994, male life expectancy dropped from 64.9 to 57.6 years. Since then, male life expectancy has recovered somewhat, but at 63 years, it is still the shortest in any developed country. Female life expectancy has not dropped as much and is now 75 years. Major causes of low life expectancies in the region are the loss of health care, which was usually tied to employment, and the physical and mental distress caused by lost jobs and social disruption. The higher male death rate is explained in large part by alcohol abuse and related suicides (women are less prone to both but tend to smoke in excess). More than half of all deaths among the working-age population are alcohol-related. On the positive side, the increases in life expectancy over the last few years indicate a modest improvement in health, which mirrors economic stabilization in Russia.

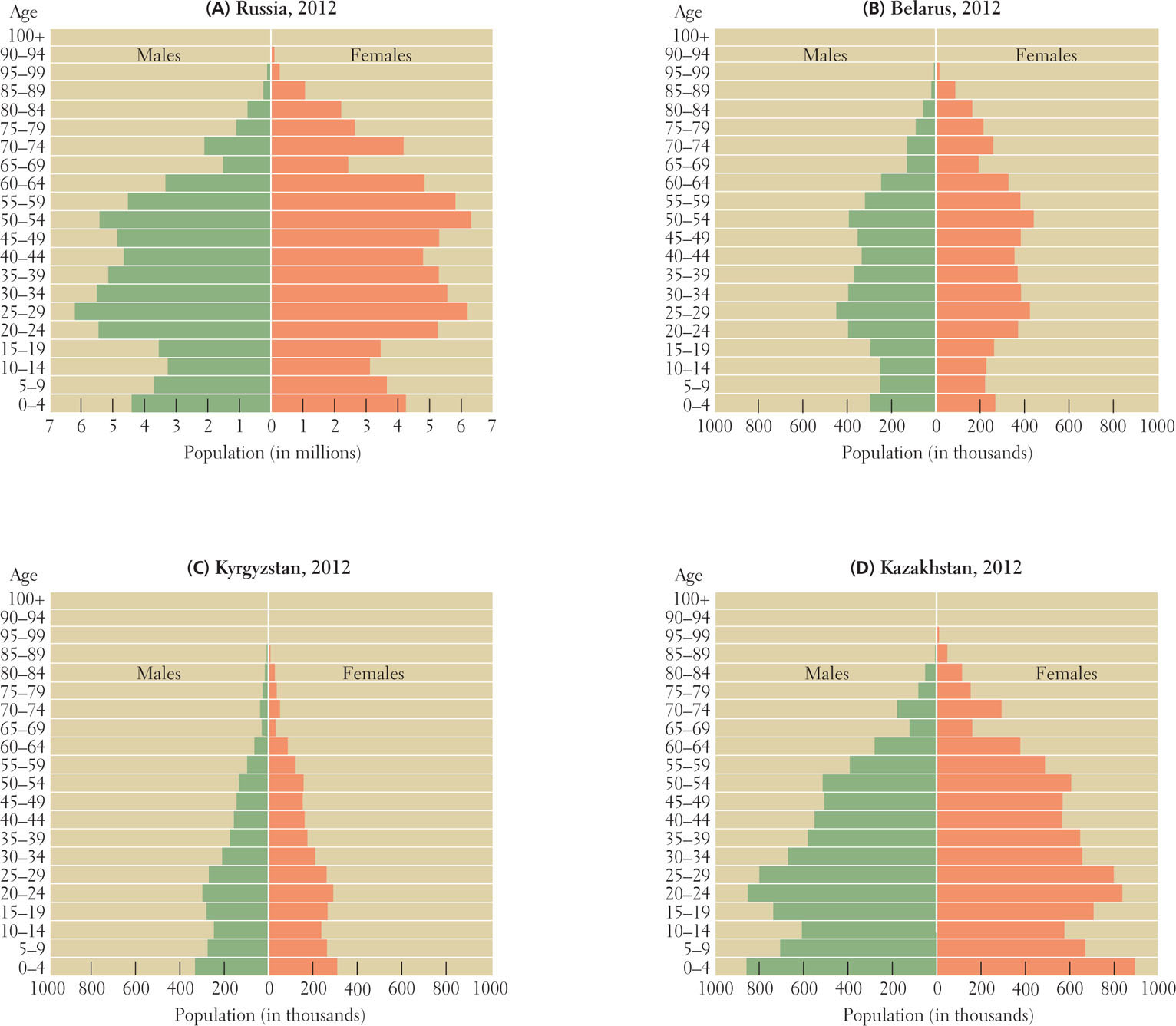

Population pyramids for several countries (Figure 5.23) show the overall population trends in the region and reflect geographic differences in patterns of family structure and fertility. The pyramids for Belarus and Russia resemble those of European countries (for example, Germany, as shown in Figure 4.21A), but there are also differences. First, they are significantly narrower at the bottom, indicating that birth rates in the last several decades have declined sharply. Because so few children are born, in 20 years there will be few prospective parents, which means that low birth rates and population decline will continue into the foreseeable future. Also, the narrower point at the top for males shows their much shorter average life span compared to that of European men. The narrow top is also evident in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In all countries, there has been a recent rebound in birth rates in the youngest age group, ranging from a slight increase in Russia to a significant rebound in Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan’s pyramid indicates a younger population structure, which is common in less affluent economies. In the Central Asian countries, if emigration is controlled, population may expand during the next decades.

Geographic Patterns of Human Well-Being

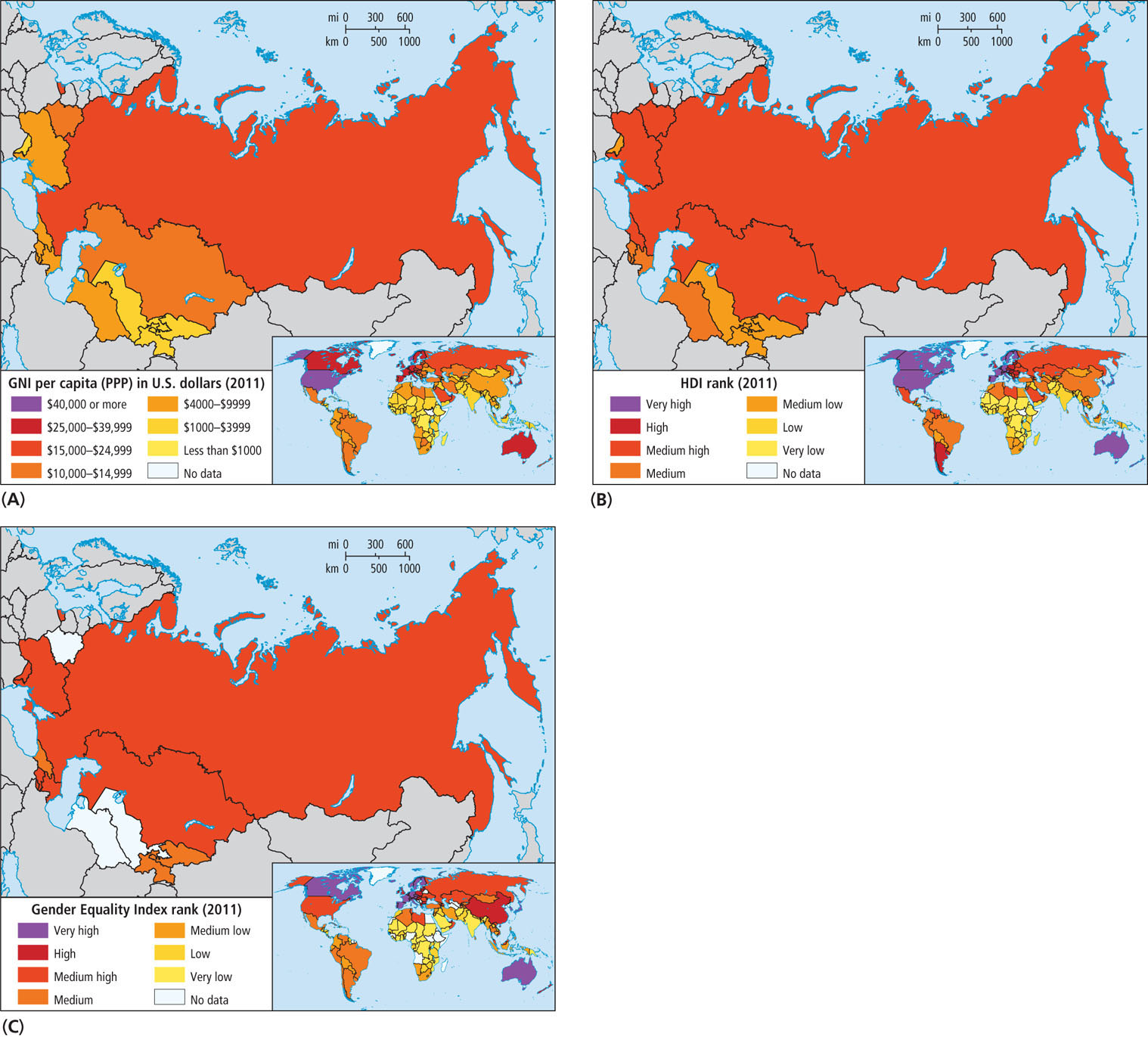

The recent increases in life expectancy and birth rates in some countries may indicate improvements in the general well-being of the population after the difficult period immediately following the Communist era. In Figure 5.24, the color maps show that Russia and the post-Soviet states mostly fall in the middle range of the three well-being indicators that are presented. Only in three of the Central Asian states and Moldova is GNI per capita (PPP) low (less than U.S.$4000 per year). All countries in the region rank from medium high to medium low in the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) and Gender Equality Index (GEI), although data on gender inequality are not available for all countries.

As we have observed elsewhere, GNI per capita can be used as a general measure of well-being because it shows in a broad way how much people in a country have to spend on necessities (see Figure 5.24A). However, because GNI per capita is averaged it does not indicate how income is distributed or how accessible health care, education, and other social services are to most people. In this particular region, the intermediate HDI ranks are in large part a holdover from the Soviet era, when socialism kept wages relatively equal (though they were usually lower on average outside of European Russia) and the strong social safety net provided basic health care, food, and housing for all. Since 1991, disparities in wealth have steadily increased within the Russian Federation and each of the post-Soviet states. We have observed that in Russia, a few people have become fabulously wealthy; their wealth has undoubtedly skewed the average figure. For many Russians, income is actually well below the country’s $14,500 GNI per capita, as Russia has changed from a society based on economic equality to one where the gap between poverty and wealth is similar to that of the United States. The post-Soviet era has also revealed significant differences in income among the new states. The GNI per capita in Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan is more than $10,000, while in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan it is only about $2000.

Figure 5.24B depicts the ranks on the HDI, which is a calculation (based on adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment) of how adequately a country provides for the well-being of its citizens. It is possible to have a low GNI rank and a higher HDI rank if social services are sufficient or if there are no wide disparities of wealth. Georgia and Ukraine are two countries that stand out as having a good HDI (medium high) compared to their modest incomes (medium low). From a global perspective, Russia and the post-Soviet states rank slightly higher on HDI relative to their GDP, which may be a leftover result of the Soviet emphasis on broad education and basic social services that improved human well-being during most of the twentieth century. The lower HDI rankings are in the same Central Asian states and Moldova that also have low GNI per capita.

Figure 5.24C shows how countries rank in gender equality. First, as is true across the globe, nowhere in the region are women close to being equal to men. However, Russia and the post-Soviet states perform a little bit better with regard to gender equality than they do in terms of their GNI and HDI. All countries are in the medium or medium-high categories. This also means that, unlike for GNI and HDI, there is little variation across the region. Again, the Soviet system, which encouraged education and careers for women, is partly responsible for this record. The country with the lowest gender equality (Georgia) is not much more unequal than the country with the highest gender equality rank (Moldova). Unlike for HDI, the geographic gender equality differences that do exist among the countries in the region seem unrelated to economic differences; that is, some countries that have less gender equality have a low GNI, while other such countries have a medium GNI.

Gender: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-Soviet Era

Geographic Insight 6

Gender: Men and women have been differently affected by the massive economic and political changes in this region during the twentieth century. Women have slowly gained economic power, while, on average, men have been adversely affected by economic instability, loss of jobs, and alcoholism.

Soviet policies that encouraged all women to work for wages outside the home have transformed this region. By the 1970s, ninety percent of able-bodied women were working full time, giving the Soviet Union the highest rate of female paid employment in the world. However, the traditional attitude that women are the keepers of the home persisted. The result was the double day for women. Unlike men, most women worked in a factory or office or on a farm for 8 or more hours and then returned home to cook, care for children, shop daily for food, and do the housework (without the aid of household appliances). Because of shortages (the result of central-planning miscalculations), they also had to stand in long lines to procure necessities for their families.

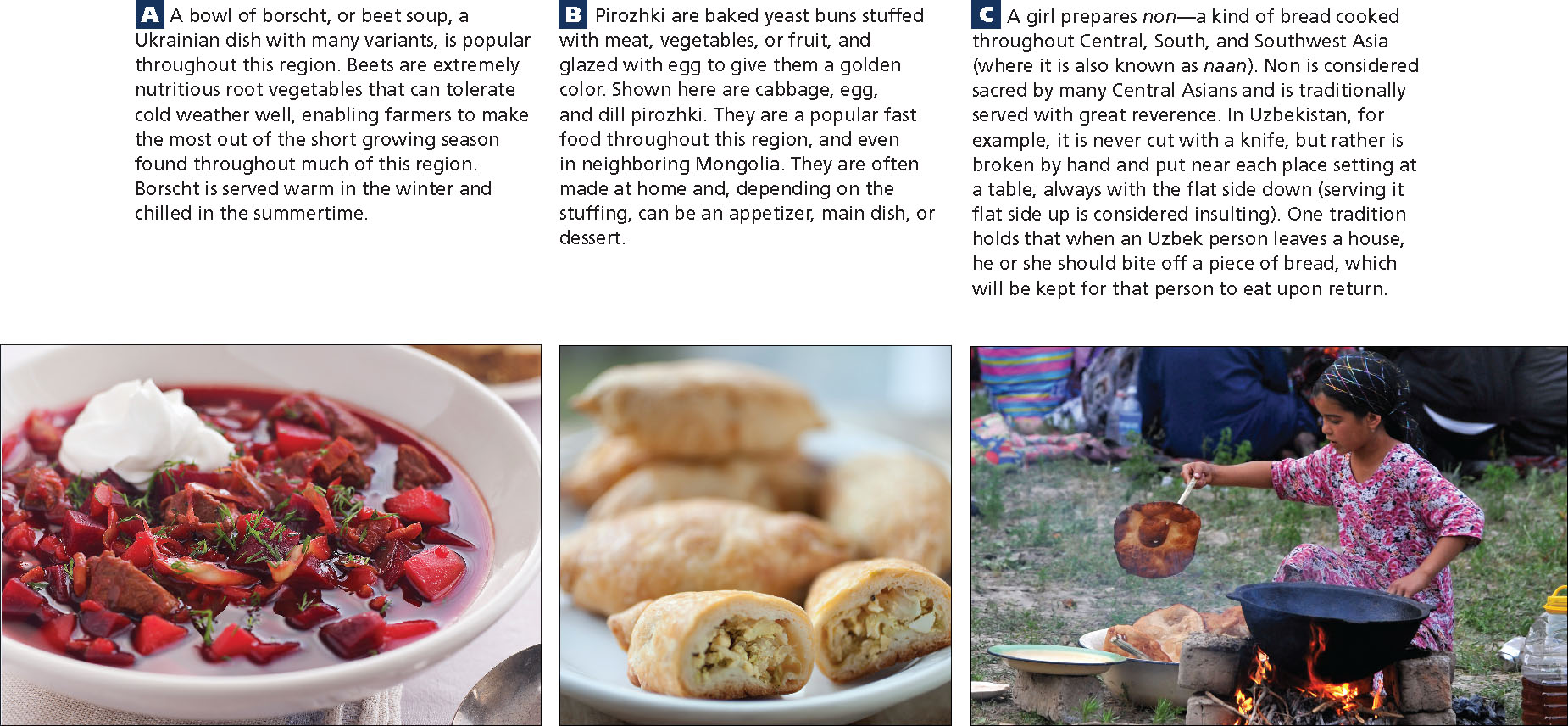

These special pressures on working women affected diets because there was so little time or space for cooking and there were so few helpful appliances. The everyday cuisine in most of the region was a bit limited during the Communist era; only recently have market forces made a wider range of food available. Traditional recipes are now being revived. Figure 5.25 shows several distinct dishes of the region that are prepared at home or in restaurants. The popularity of hearty soups and stews and the common use of root vegetables and grains (bread is an essential part of every meal) reflect the region’s climate, soil, and agricultural systems.

When the first market reforms in the 1980s reduced the number of jobs available to all citizens, President Gorbachev encouraged women to go home and leave the increasingly scarce jobs to men. Many women lost their jobs involuntarily. By the late 1990s, women made up 70 percent of the registered unemployed, despite the fact that because of illness, death, or divorce, many if not most were the sole support of their families. Consequently, many had to find new jobs.

On average, the female labor force in Russia is now more educated than the male labor force. The same pattern is emerging in Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, and parts of Muslim Central Asia. In Russia, the best-educated women commonly hold professional jobs, but they are unlikely to hold senior supervisory positions. They also are paid less than their male counterparts. In 2007, the wages of women professional workers averaged 36 percent less than those of men. Still, this region ranks higher in gender income equity than many others.

The Trade in Women

During the economic boom stimulated by marketization and oil and gas wealth, the “marketing” of women became one of the less savory entrepreneurial activities. One part of this market is the Internet-based mail-order bride services aimed at men in Western countries. A woman in her late teens or early twenties, usually seeking to escape economic hardship, pays about $20 to be included in an agency’s catalog of pictures and descriptions. (One Internet agency advertises 30,000 such women.) She is then assessed via e-mail or Facebook by the prospective groom, who then travels—usually to Russia or Ukraine—to meet women he has selected from the catalog and to potentially have one of them accompany him to the West to marry.

trafficking the recruiting, transporting, and harboring of people through coercion for the purpose of exploiting them

The Political Status of Women

The most effective way for women to address institutionalized discrimination is to gain access to positions from which they can affect wide-ranging policies—usually as elected officials. Although women were granted equal rights in the Soviet constitution, they have never held much power. In 1990, women accounted for 30 percent of Communist Party membership but just 6 percent of the governing Central Committee. The very few in party leadership often held these positions at the behest of male relatives.

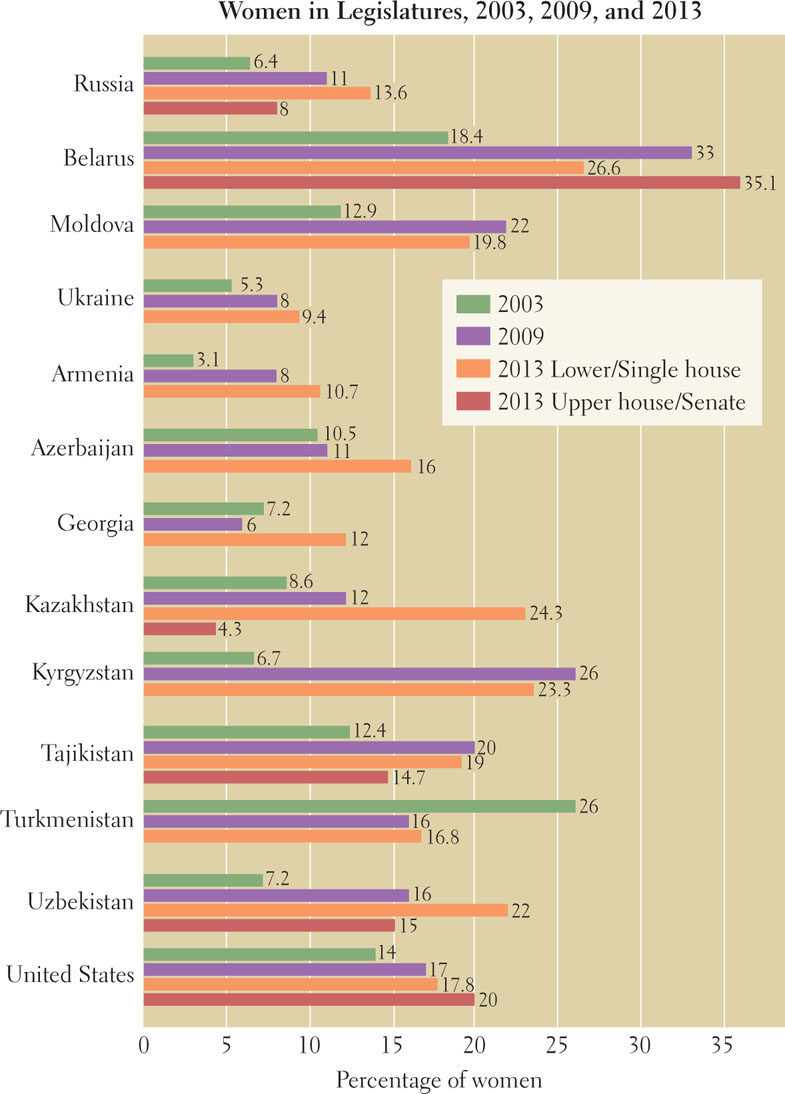

Ironically, since the fall of the Soviet Union, the political empowerment of women has advanced the least where democracy has developed the most, perhaps because of long-standing cultural biases against women in positions of power. Where governments are less democratic and more authoritarian, as in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, women actually hold more legislative positions (Figure 5.26). However, in those countries, leaders who wanted to appear more progressive in the eyes of international donors may have promoted women undemocratically, choosing those who were least likely to work for change. Ironically, support among women for women’s political movements is not widespread, as many fear being seen as anti-male or against traditional feminine roles.

Religious Revival in the Post-Soviet Era

The official Soviet ideology was atheism, and religious practice and beliefs were seen as obstacles to revolutionary change. The Orthodox Church was tolerated, but few went to church, in part because the open practice of religion could be harmful to one’s career. Now, religion is a major component of the general cultural revival across the former Soviet Union. This may be happening because people turn to traditional practices during uncertain times, or as a way to assert their ethnic identity. The overall level of religious practice is moderate in Russia by global comparisons, but a number of people, especially those from indigenous ethnic minority groups, are turning back to ancient religious traditions. For example, the Buryats, from east of Lake Baikal in Siberia, who are related to the Mongols, are relearning the prayers and healing ceremonies of the Buryat version of Tibetan Buddhism, which they adopted in the eighteenth century. The shamans who lead them have organized into a guild to give official legitimacy to their spiritual work. They now pay taxes on their clergy income.

In Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Georgia, and Armenia, most people have some ancestral connection to Orthodox Christianity. Those with Jewish heritage form an ancient minority, mostly in the western parts of Russia and Caucasia, where they trace their heritage back to 600 b.c.e. Religious observance by both groups increased markedly in the 1990s, and many sanctuaries that had been destroyed or used for nonreligious purposes by the Soviets were rebuilt and restored.

A countertrend to the robust revival of Orthodox Christianity is the spread of evangelical Christian sects from the United States (Southern Baptists, Adventists, and Pentecostals). Evangelical Christianity first came to Russia in the eighteenth century, but after 1991, American missionary activity increased markedly. The notion often promoted by this movement—that with faith comes economic success—may be particularly comforting both to those struggling with hardship and to those adjusting to new prosperity.

In Central Asia, Islam was long repressed by the Soviets, who feared Islamic fundamentalist movements would cause rebellion against the dominance of Russia. Today, Islam is openly practiced and increasingly important politically across Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and some of the Russian Federation’s internal ethnic republics, such as Chechnya and Tatarstan. Especially in the Central Asian states, however, the return to religious practices is often a subject of contention. Some local leaders still view traditional Muslim religious practices as obstacles to social and economic reform.

Both devout Muslims and more secular reformists are wary of religious extremists from Iran and Saudi Arabia who may pose a security risk. During the 1990s, Tajikistan fought a civil war against Islamic insurgents with links to the Taliban in Afghanistan—and the conflict in Chechnya involves combatants with similar links to Saudi militants. In 2000, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan joined forces to eliminate an extremist Islamic movement. But many religious leaders and some human rights groups say that the fervor to eliminate radical insurgents has resulted in the persecution of ordinary devout Muslims, especially men, and that this persecution is recruiting anti-Western enthusiasts. Human Rights Watch, an organization that monitors human rights abuses worldwide, reports that Uzbekistan’s government jails and tortures believers who worship independently outside the strict supervision of the state. The authorities are concerned that the Arab Spring (see Chapter 6) will spread and lead to demands for more human rights and religious freedom in Uzbekistan too.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 5Population Population trends in this region are highly uneven. Russia and the countries bordering Europe have the most rapidly declining populations on Earth. Meanwhile, the Central Asian and Caucasian countries have higher birth rates, though they are still losing people to emigration.

Geographic Insight 5Population Population trends in this region are highly uneven. Russia and the countries bordering Europe have the most rapidly declining populations on Earth. Meanwhile, the Central Asian and Caucasian countries have higher birth rates, though they are still losing people to emigration. An uneven pattern of urbanization is developing in this region. In several countries, the largest cities are growing rapidly, as they are centers of new economic development and globalization. Meanwhile, in Russia and elsewhere, many cities and rural regions are shrinking as the overall population declines.

An uneven pattern of urbanization is developing in this region. In several countries, the largest cities are growing rapidly, as they are centers of new economic development and globalization. Meanwhile, in Russia and elsewhere, many cities and rural regions are shrinking as the overall population declines. Geographic Insight 6Gender The Soviet Union gave strong incentives for women to work and become involved in politics, but in the post-Soviet era, gaps have been increasing between men and women in employment rates and political representation. New threats to women have also emerged, such as international prostitution rings, now active in some countries.

Geographic Insight 6Gender The Soviet Union gave strong incentives for women to work and become involved in politics, but in the post-Soviet era, gaps have been increasing between men and women in employment rates and political representation. New threats to women have also emerged, such as international prostitution rings, now active in some countries. Official Soviet ideology was atheism, and religious practice and beliefs were seen as obstacles to revolutionary change. In the post-Soviet era, religion is a major component of the general cultural revival.

Official Soviet ideology was atheism, and religious practice and beliefs were seen as obstacles to revolutionary change. In the post-Soviet era, religion is a major component of the general cultural revival.