6.1 6 North Africa and Southwest Asia

6.1.1 Geographic Insights: North Africa and Southwest Asia

Geographic Insights: North Africa and Southwest Asia

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Water, Food, and Climate Change: The population of this predominantly dry region is increasing faster than is access to cultivable land and water for agriculture and other human uses. Many countries here are dependent on imported food, and because global food prices are unstable, the region often has food insecurity. Climate change could reduce food output both locally and globally and make water, already a scarce commodity, a source of conflict. New technologies offer solutions to water scarcity but are expensive and unsustainable.

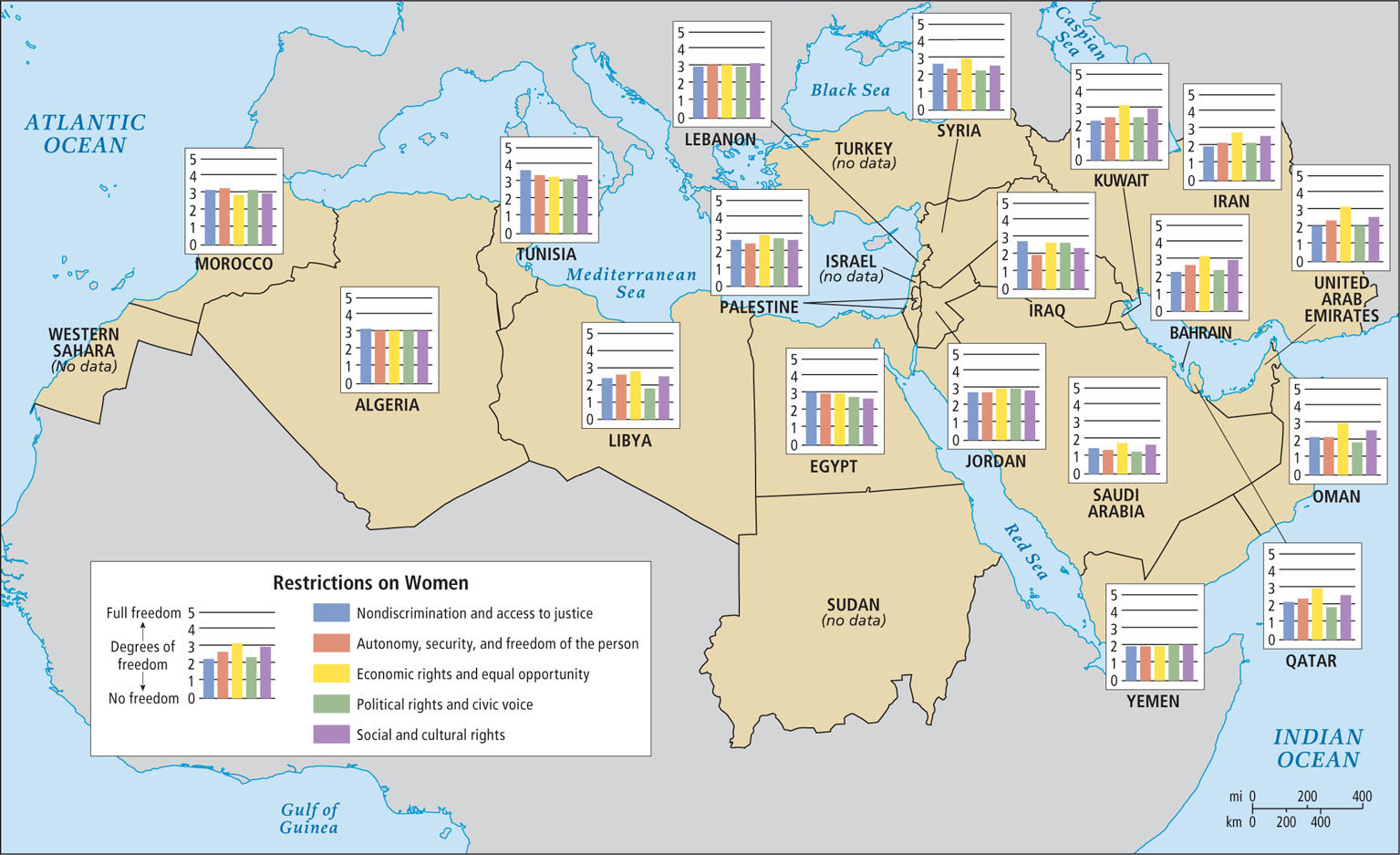

2. Gender and Population: Gender disparities are becoming more noticeable in this region as political change begins to occur. Women are dependent because they are generally less educated than men, have few options for working outside the home, and have little access to political power. Women’s roles are usually confined to the home and to having and raising children. As a result, this region has the second-highest population growth rate in the world, after sub-Saharan Africa.

3. Urbanization and Globalization: Two patterns of urbanization have emerged in the region, both tied to the global economy. In the oil-rich countries, the development of spectacular new luxury-oriented urban areas is based on flows of money, credit, goods, and skilled people. But most cities are old, with little capacity to handle the mass of poor, rural migrants attracted by export industries aimed at earning foreign currency. In these older cities, many people live in overcrowded slums with few services.

4. Development and Globalization: The vast fossil fuel resources of a few countries have transformed economic development and driven globalization in this region. In these countries, economies have become powerfully linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. Politics have also become globalized, with Europe and the United States strongly influencing many governments.

5. Power, Politics, and Gender: Despite the predominance of elected bodies of government, and the increasing participation of women as voters, wealthy, politically connected males, clerics, and often the military retain the real power. Waves of protest, which included some women participants, swept this region, beginning with the Arab Spring of 2010, and resulted in the overthrow of several authoritarian governments. Within the region, official response to the Arab Spring has included both repression and reforms, but only a few of the positive changes hold promise for women.

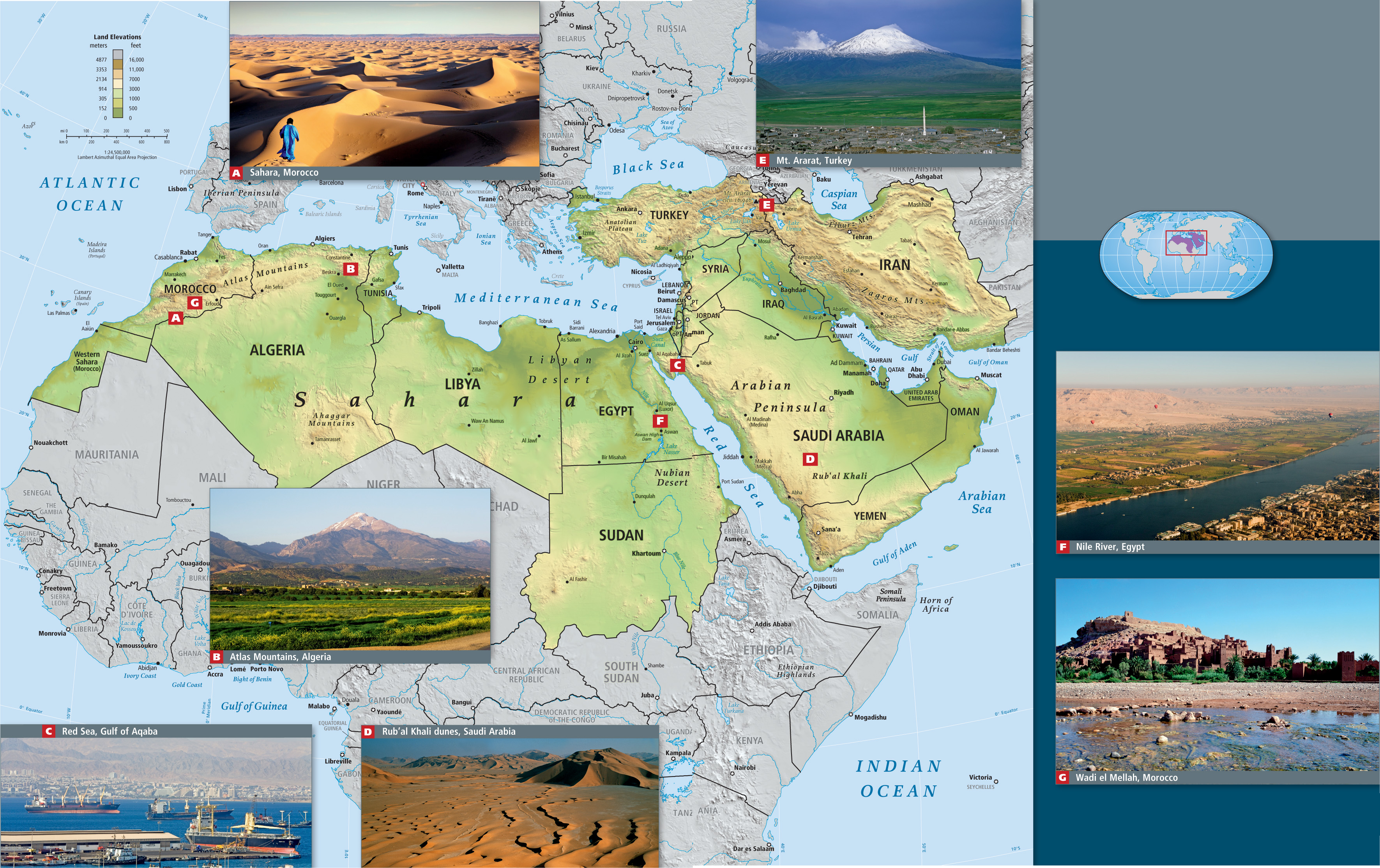

The North African and Southwest Asian Region

The region of North Africa and Southwest Asia contains 21 countries plus the occupied Palestinian Territories (see Figure 6.1; see also Figure 6.2). Physically, the region is part of two continents: Africa and Eurasia. The North African countries of this region stretch from Western Sahara and Morocco on the Atlantic Ocean, through Algeria, Tunis, Libya, and Egypt along the Mediterranean Sea, plus Sudan, lying south of Egypt. Eurasia begins on the eastern side of the Red Sea with the Arabian Peninsula, which consists of Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait (see Figure 6.1C); the countries of the eastern Mediterranean littoral (shoreline), including Jordan, Israel, the occupied Palestinian Territories, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. Iraq and Iran lie inland. In political discussions, this region is often referred to as the Middle East, a term we do not use in this book because it arose during the colonial era and describes the region from a limited Euro-American geographic perspective. To someone in China or Japan, the region lies to the far west, and to someone in Russia, it lies to the south.

The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights on this page. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the rising role of women in this region, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

When in the spring of 2012, Mona Eltahawy, a Muslim Egyptian-American journalist, wrote an essay for Foreign Policy magazine entitled “Why Do They Hate Us?” she was angry. It is easy to see why. The Arab Spring—that seemingly merry embrace of democracy that washed across North Africa and into Egypt, beginning in 2010—held the promise of real change in her native land. For a time, the tens of thousands of largely peaceful demonstrators, male and female, in Cairo’s Tahrir Square shared a common purpose: the resignation of the autocratic president, Hosni Mubarak. He had remained in power for nearly 30 years, aided by a powerful and oppressive military, and supported by internal corruption and large foreign aid packages from the United States.

For the many thousands of women—students and young professionals—who participated in the Cairo demonstrations, it was exhilarating to be welcomed by male compatriots, many of whom were members of the Muslim Brotherhood, a large and amorphous organization of men opposed to the corrupt Mubarak regime and its affiliations with the West. The Muslim Brotherhood, however, is also known for its stance against liberalizing women’s rights. For a time, the common purpose of ousting Mubarak united everyone. Eltahawy, who grew up in Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and Egypt, and who has focused her career on social justice and women’s rights in Egypt, joined the throng of demonstrators. As the protests went on, not only did retaliation by the military and police toward male and female demonstrators become more and more brutal, but antagonism toward women by the Muslim Brotherhood demonstrators and even from young, more liberal male demonstrators grew, leading to random violence by men against women (Figure 6.3). Mubarak’s resignation in February 2011 left undetermined the way in which a new government would be established; so as the military asserted control, the demonstrations continued. One day in the fall of 2011, Eltahawy, who continued to report on the increasingly frustrated demonstrators in Tahrir Square, was arrested along with some others. While in custody, both her arms were broken in a beating, and she was sexually assaulted—a type of treatment that she observed was especially aimed at women demonstrators.

In her essay, which she wrote some months after her release, Eltahawy raged against the repressive political authorities, whom she held in contempt, and against Muslim men as a whole, who she had hoped would have exhibited solidarity with women demonstrators. Her anticipation that gender equity would be one of the end products of the Arab Spring was dashed by what she saw and experienced, so she lashed out with a diatribe against the many large and small ways in which she perceives women are belittled—not by the Qur’an, but by religious social practice in Egypt and elsewhere (Figure 6.4). In so expressing her rage, Eltahawy seems to have invigorated a cross-regional discussion on gender equity that is attracting serious male and female participants who are expressing a surprising level of agreement that the Arab Spring must include the human rights of women. [Source: Foreign Policy, Al Jazeera. For more detailed information, see Text Credits page.]

The Arab Spring, a movement that will likely continue evolving for decades, is just one more revolution brought on by the post-colonial awareness that all societies have inequities of some sort that must be addressed. The issues raised are deep and structural and political; that is, they have to do with realigning power so that whole segments of society—the poor, the uneducated, the educated unemployed, minorities, and women—will no longer be subjugated by systems that favor privileged elites.

The issue of gender equity in the region of North Africa and Southwest Asia is controversial because many people are convinced that only Westerners raise this issue, and that they do so in order to browbeat Muslim culture for having a set of values that places females in a special category. But Mona Eltahawy’s article and, more importantly, the discussions that have erupted about it across the region indicate that gender equity is actually a central theme in the Arab Spring movement. The taboo against talking about gender is fading slightly, as demonstrated in broadcasts by the global Al Jazeera network based in Qatar. Some women in the region are beginning to say that it is they who will lead the transformation.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Arab Spring, a broad-based but not highly organized movement against corruption and toward more democratic institutions, has spread across the region since 2010.

The Arab Spring, a broad-based but not highly organized movement against corruption and toward more democratic institutions, has spread across the region since 2010. Women are increasingly participating in political movements but continue to face difficulties in doing so.

Women are increasingly participating in political movements but continue to face difficulties in doing so. Issues of gender equity are increasingly becoming central to the public dialogue.

Issues of gender equity are increasingly becoming central to the public dialogue.