Environmental Issues

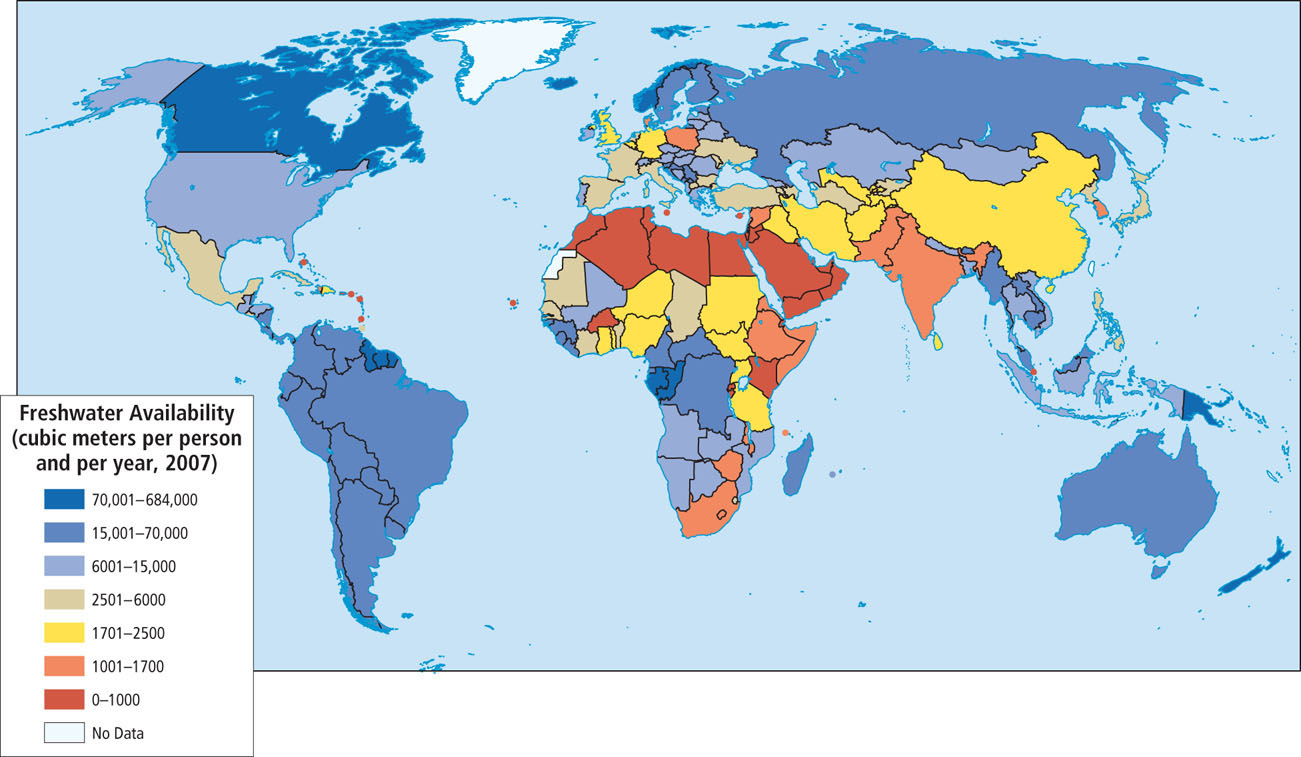

Environmental concerns are only beginning to be an overt focus in this region. This is in part because for thousands of years people here have confronted the challenges of a naturally arid environment and have been quite attuned to its scarcities, which exceed those in most other places on Earth (Figure 6.6).

An Ancient Heritage of Water Conservation

Geographic Insight 1

Water, Food, and Climate Change: The population of this predominantly dry region is increasing faster than is access to cultivable land and water for agriculture and other human uses. Many countries here are dependent on imported food, and because global food prices are unstable, the region often has food insecurity. Climate change could reduce food output both locally and globally and make water, already a scarce commodity, a source of conflict. New technologies offer solutions to water scarcity but are expensive and unsustainable.

Qur’an (or Koran) the holy book of Islam, believed by Muslims to contain the words Allah revealed to Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel

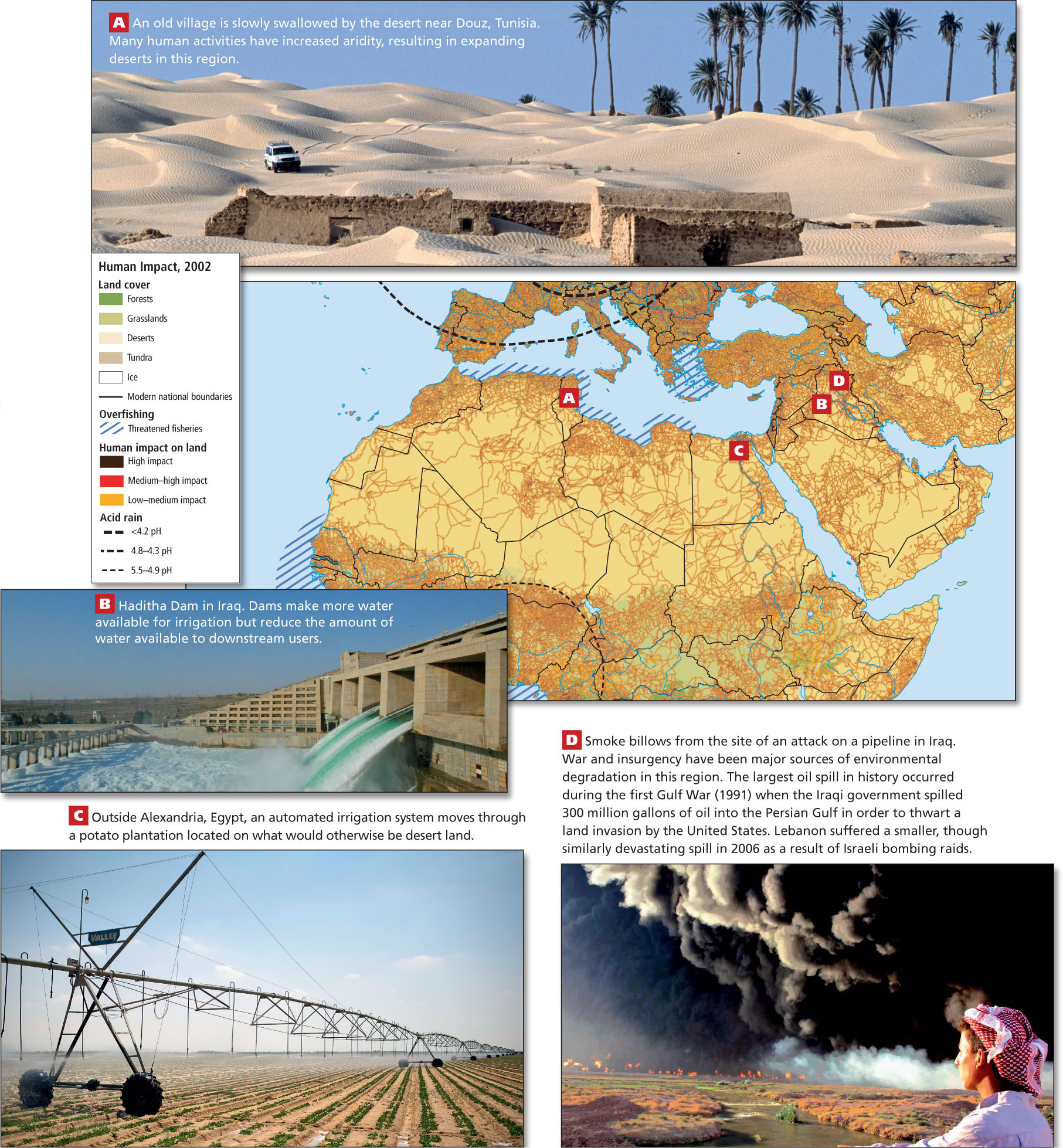

Despite their long history of water-conserving technologies and practices, however, this region’s 477 million residents now have such limited water resources that even clever combinations of ancient and modern measures are no longer sufficient to ensure an adequate supply of water. Growing populations, water pollution, and unwise modern usages of water virtually guarantee that water shortages will be more extreme in the future (Figure 6.7A-D), especially with the likelihood of climate change-related drier conditions. As shown in the map in Figure 6.6, Turkey has the most plentiful water resources, followed by Iran, Iraq, and Syria. However, all other countries in the region suffer from freshwater scarcity, meaning that they are close to or below the minimum the United Nations considers necessary to support basic human development—1000 cubic meters per person per year.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human impacts on the biosphere in North Africa and Southwest Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What about a dam creates soil moisture problems for downstream users of river water once the dam is operational?

What about a dam creates soil moisture problems for downstream users of river water once the dam is operational?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How might a dam like the Aswan on the upper part of the Nile River in Egypt contribute to soil salinity and lowered fertility in lowland regions once naturally flooded by now irrigated pump water?

How might a dam like the Aswan on the upper part of the Nile River in Egypt contribute to soil salinity and lowered fertility in lowland regions once naturally flooded by now irrigated pump water?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Could There Be New Sources of Water?

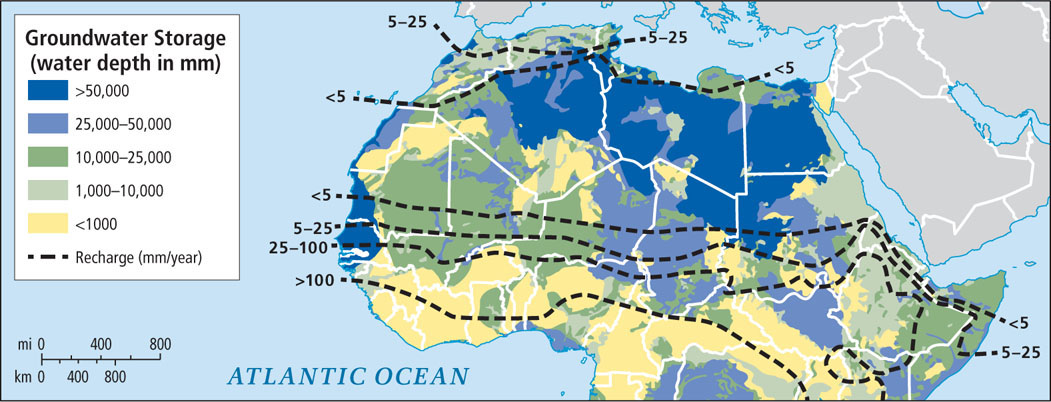

A very recent reassessment of groundwater storage in North Africa by a consortium of British scientists revealed that water stored by nature in deep aquifers may amount to 100 times that available through renewable freshwater resources (Figure 6.8). However, this fossil water that was deposited thousands of years ago is unlikely to be replenished and is unevenly distributed and difficult to access. Large quantities of fossil water are in sedimentary aquifers beneath Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and Sudan, but the water lies too deep to be brought up with simple pumps and is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the expected increases in demand for agricultural irrigation and for consumption by rapidly growing urban populations. Nonetheless, quantifying and mapping the stored groundwater provides a base for determining how to accommodate scarcities caused by climate variability.

Water and Food Production

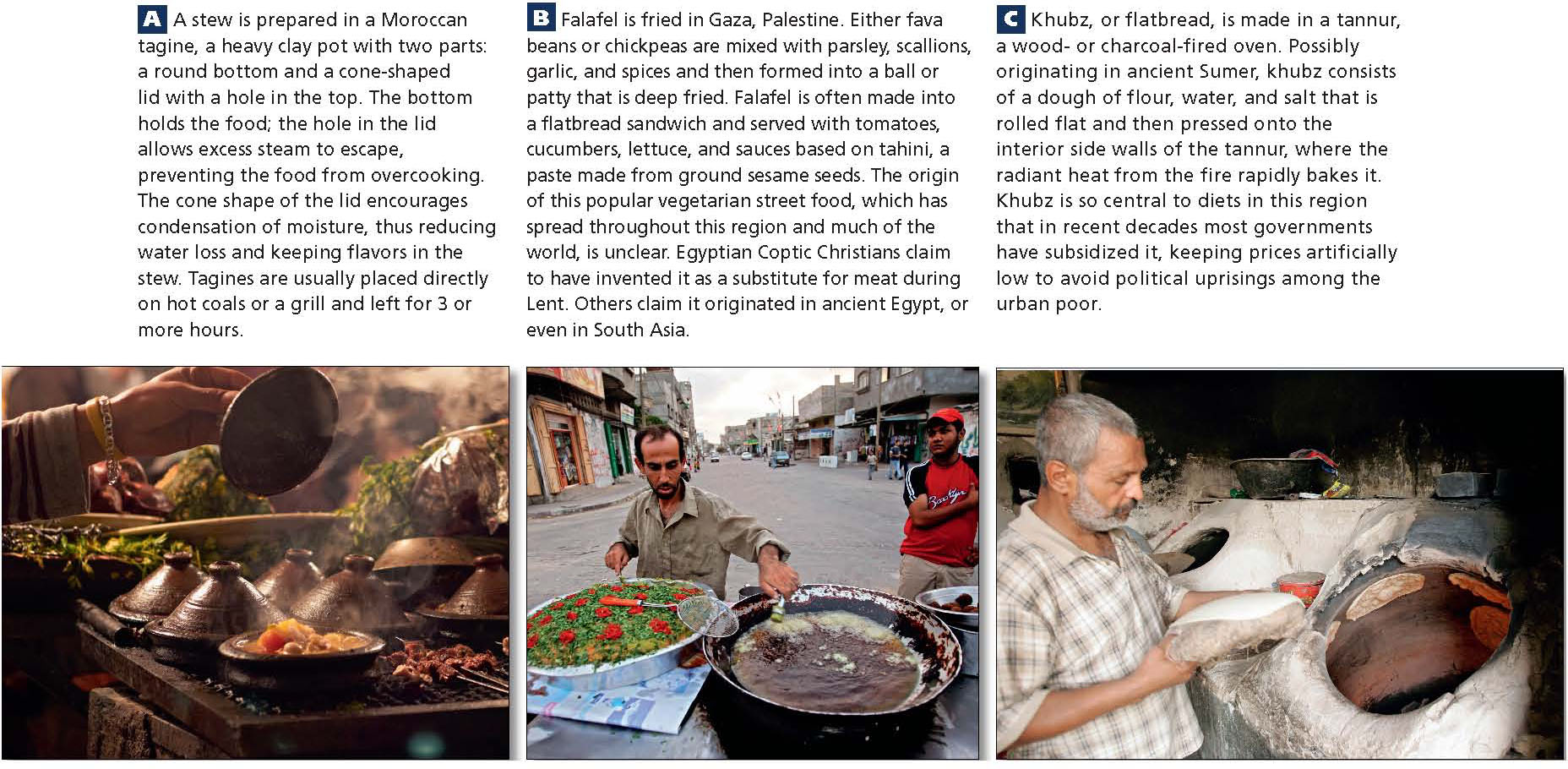

The predominant use of water in North Africa and Southwest Asia is for irrigated agriculture, even though agriculture does not contribute significantly to national economies. In Tunisia, for example, agriculture accounts for just 10 percent of GDP but 86 percent of all the water used. Only 13 percent of water is used in homes, and only 1 percent by industry. Some justification for the large amount of water used by agriculture in this water-stressed region may be found in the value that irrigated agriculture has in rural areas for local food production, jobs, and family economies. Most countries, to help control reliance on imports, subsidize irrigation for food and fiber crops in some way. Some of this region’s food specialties appear in Figure 6.9.

Until the twentieth century, agriculture was confined to a few coastal and upland zones where rain could support cultivation, and to river valleys (such as the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates valleys), where farms could be irrigated with simple gravity-flow technology. However, to accommodate population growth and development, Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Syria, Turkey, Israel, and Iraq all now have ambitious mechanized irrigation schemes that have expanded agriculture deep into formerly uncultivable arid environments (see Figures 6.5B and 6.7B, C).

salinization a process that occurs when large quantities of water are used to irrigate areas where evaporation rates are high, leaving behind salts and other minerals

Israel has developed relatively efficient techniques of drip irrigation that dramatically reduce the amount of water used, thereby limiting salinization and freeing up water for other uses. Until very recently, however, poorer states have been unable to afford this somewhat complex technology, which requires an extensive network of hoses and pipes to deliver water to each plant. Arab countries resist depending on a technology developed by Israel—a country they deeply distrust.

Vulnerability to Climate Change

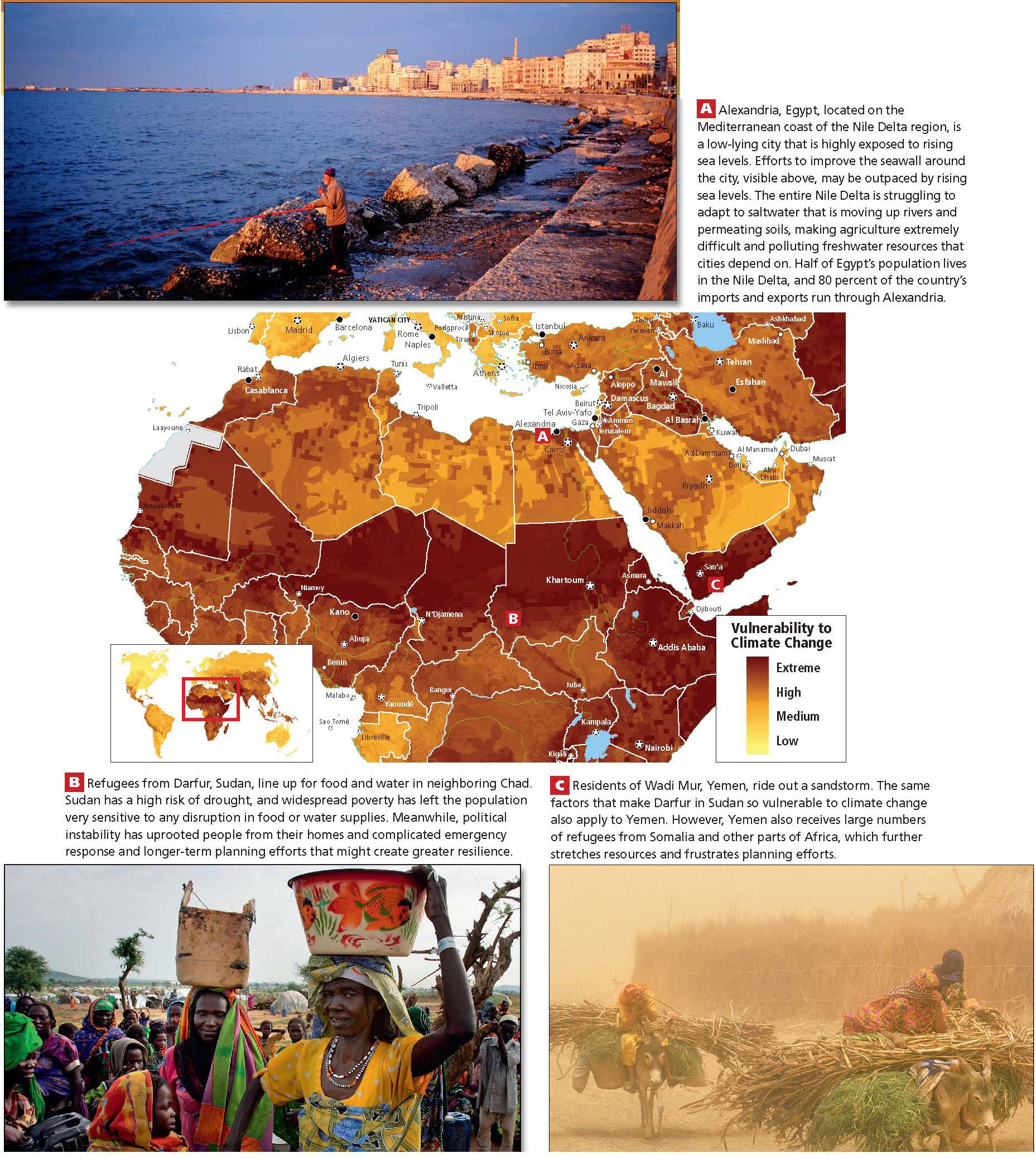

North Africa and Southwest Asia are especially vulnerable to the multiple effects of climate change, both in the region and beyond. Global warming is already changing rainfall patterns and increasing evaporation rates where water scarcity has long required accommodation (see Figure 6.7A; see also Figure 6.10B, C). These climatic changes, along with people’s intensified use of water, are transforming more nondesert lands into deserts. Also, as the climate warms, a sea level rise of a few feet could severely impact the Mediterranean coast, especially the Nile Delta, one of the poorest and most densely populated lowland areas in the world (see Figure 6.10A), and the Persian Gulf coasts, where vast new high-tech cities that lie at sea level would likely be flooded (see Figure 6.23A). Conversely, under some climate-change scenarios, periods of unusually intense rainfall could increase flooding.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the vulnerability to climate change in North Africa and Southwest Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What about Alexandria's location makes it particularly vulnerable to sea level rise?

What about Alexandria's location makes it particularly vulnerable to sea level rise?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What are some of the factors in the region that complicate emergency responses to climate change, thus limiting resilience?

What are some of the factors in the region that complicate emergency responses to climate change, thus limiting resilience?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How does Yemen's situation as a haven for refugees from nearby countries make it more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change?

How does Yemen's situation as a haven for refugees from nearby countries make it more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Independent of any environmental effects of climate change, global efforts to reduce dependencies on fossil fuel consumption could devastate oil- and gas-based economies and transform the region’s geopolitics, leaving countries vulnerable to losing some of their global power and to having lower overall income levels. Despite the enormous wealth from fossil fuel sales that has flowed into some of these countries over the past 40 years, few countries have undertaken the significant economic diversification needed to prepare for the reduced global consumption of the fossil fuels they sell.

Climate Change and Desertification

desertification a set of ecological changes that converts arid lands into deserts

In the grasslands (steppes) that often border deserts, a wide array of land use changes contribute to the general drying. For example, as groundwater levels fall because water is being pumped out for cities and irrigated agriculture, some plant roots no longer reach sources of moisture, causing the plants to die. In other cases, international development agencies have inadvertently contributed to desertification by encouraging nomadic herders to take up settled cattle ranching of the type practiced in western North America. Agencies encourage settlement because the mobility of nomads is viewed as complicating management for modern state bureaucracies where records must be kept, taxes collected, and children sent to school with regularity. However, ranching on fragile grasslands can lead to overgrazing, which can kill the grasses and increase evaporation. If irrigation is used to support ranching, such projects can also deplete groundwater resources, resulting in long-term desertification. Incidentally, encouraging nomads to settle may actually increase their vulnerability to climate change, because it is their very mobility and skills at cycling seasonally through multiple environments that have long helped nomads adapt to climate variability.

Imported Food, Virtual Water, and Global Climate Change

Because agriculture is so difficult due to the aridity of this region, the diets of nearly all people here include imported food. To gain an understanding of total per capita water use, add the water used to produce this imported food, wherever it originates, to the overall water consumption by the citizens of this region. Virtual water, now a widely accepted term in water scarcity discussions, is the volume of water used to produce all that a person consumes in a year (see Chapter 1). For example, 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of beef requires 15,500 liters (4094 gallons) of water to produce, while 1 kilogram of goat meat requires just 4000 liters (1056 gallons). Goat meat, which is popular in this region and produced locally, has a much less significant water component than beef, but beef consumption is on the rise. One kilogram of corn requires 900 liters (238 gallons) of water, and 1 kilogram of wheat, 1350 liters (357 gallons). Beef, corn, and wheat are common imports; in fact, North Africa and Southwest Asia is the region with the world’s largest consumption of imported wheat. The most disturbing aspect of dependence on imported food and virtual water is that climate change is reducing water availability in China, Russia, Ukraine, and the Americas—all places that supply wheat and other food to the countries of this region.

Strategies for Increasing Access to Water

Some strategies have been developed for increasing supplies of fresh water, but each presents a set of difficulties. All of them are expensive, some have enormous potential to cause increased wasting of water, and most do not guarantee equal access to the increased supply.

seawater desalination the removal of salt from seawater—usually accomplished through the use of expensive and energy-intensive technologies—to make the water suitable for drinking or irrigating

Groundwater pumping Many countries pump groundwater from underground aquifers to the surface for irrigation or drinking water. Under Muammar el-Qaddafi, Libya had invested some of its earnings from fossil fuels into one of the world’s largest groundwater pumping projects, known as the Great Man-Made River. This project draws on part of the ancient fossil water deposit mentioned above to supply almost 2 billion gallons of water per day to Libya’s coastal cities and to 600 square miles of agricultural fields. With this irrigated agriculture, Libya had hoped to grow enough food to end its current food imports and even supply food to the EU. However, the rate of natural replenishment of the aquifer is far slower than the rate of extraction, making this use of groundwater unsustainable. Hydrologists report fissures in the land surface above the aquifer that they associate with land sinking, or subsidence, as the water is withdrawn. Seawater intrusion is also a problem; as fresh water is withdrawn, seawater flows into aquifers and wells in coastal zones, rendering the water brackish.

Dams and reservoirs Dams and reservoirs built on the regions’ major river systems to increase water supplies have created new problems. In Egypt, for example, the natural cycles of the Nile River have been altered by the construction of the Aswan dams. Downstream of these two dams, water flows have been radically reduced, making it necessary to use supplemental irrigation, which leads to soil salinization (see Figure 6.7C), and the lack of floods means that fertility-enhancing silt is no longer deposited on the land. As a result, expensive fertilizers are now necessary. Moreover, with less water and silt coming downstream, parts of the Nile Delta are sinking into the sea. Upstream, the artificial reservoir created by the dams has flooded villages, fields, wildlife habitats, and historic sites and created still-water pools that harbor parasites. Dams can also cause hardship across borders. The Aswan High Dam sits on Egypt’s border with Sudan, long an area of contention.

Dams as water-acquisition strategies strain cross-border relations The need to share the water of rivers that flow across or close to national boundaries often impedes national development efforts. Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project, which involves the construction of several large dams on the upper reaches of the Euphrates River for hydropower and irrigation purposes, has reduced the flow of water to the downstream countries of Syria and Iraq (Figure 6.11). In negotiations over who should get Euphrates water, for example, Turkey argues that it should be allowed to keep more water behind its dams because the river starts in Turkey and most of its water originates there as mountain rainfall. Meanwhile, Iraq’s claim to the water is linked to the fact that the Euphrates travels the longest distance in Iraq.  285. THE JORDAN RIVER IS DYING

285. THE JORDAN RIVER IS DYING

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Landforms and climates are particularly closely related In this region, and it is the driest region in the world. Rolling deserts and steppes cover most of the land. In a few places, mountains capture moisture, allowing plants, animals, and humans to flourish, but sustainability is becoming more difficult.

Landforms and climates are particularly closely related In this region, and it is the driest region in the world. Rolling deserts and steppes cover most of the land. In a few places, mountains capture moisture, allowing plants, animals, and humans to flourish, but sustainability is becoming more difficult. Geographic Insight 1Water, Food, and Climate Change As thepopulation of this dry region increases and the consumption of water and food goes up, obtaining enough cultivatable land and water for agriculture is becoming harder. Many countries are dependent on imported food, which is vulnerable to global food price rises. Climate change could reduce food output both locally and globally and change the availability of food and water, possibly resulting in civil disorder. New technologies may offer solutions but are expensive and often not sustainable.

Geographic Insight 1Water, Food, and Climate Change As thepopulation of this dry region increases and the consumption of water and food goes up, obtaining enough cultivatable land and water for agriculture is becoming harder. Many countries are dependent on imported food, which is vulnerable to global food price rises. Climate change could reduce food output both locally and globally and change the availability of food and water, possibly resulting in civil disorder. New technologies may offer solutions but are expensive and often not sustainable.