Human Patterns over Time

Important developments in agriculture, societal organization, and urbanization took place long ago in this part of the world. Also, three of the world’s great religions were born here: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Agriculture and the Development of Civilization

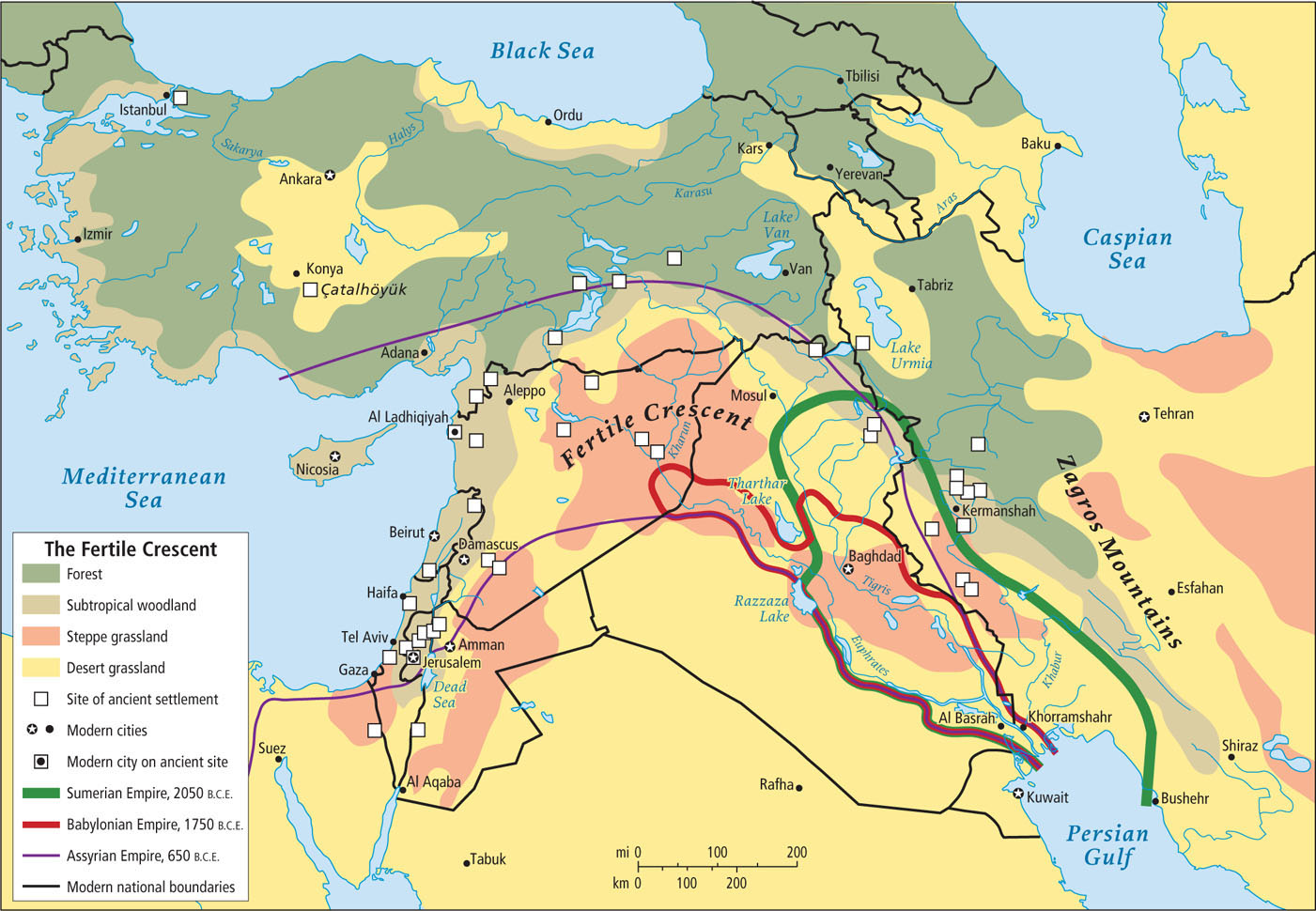

Fertile Crescent an arc of lush, fertile land formed by the uplands of the Tigris and Euphrates river systems and the Zagros Mountains, where nomadic peoples began the earliest known agricultural communities

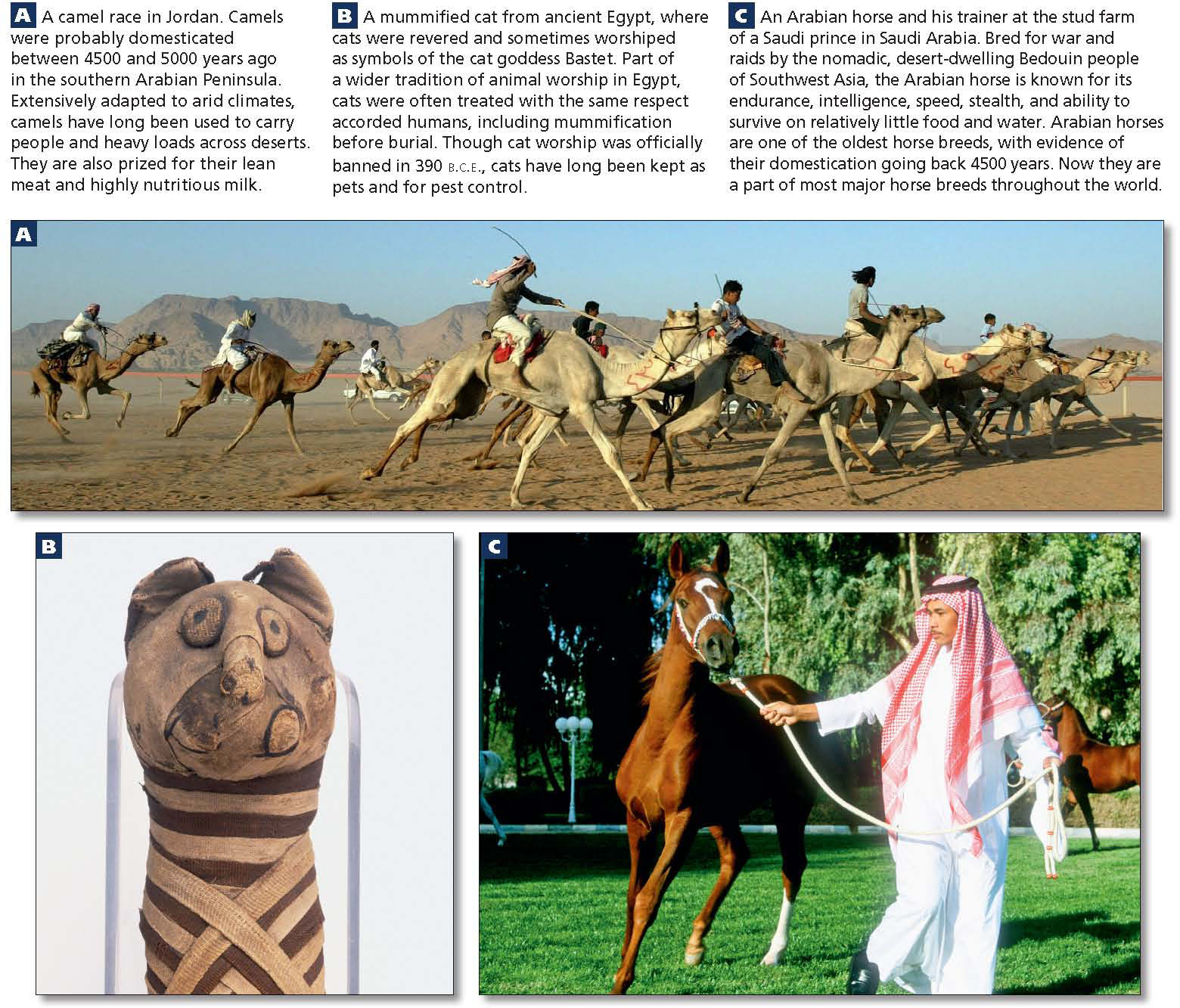

The skills of these early people in domesticating plants and animals allowed them to build ever more elaborate settlements. The settlements eventually grew into societies based on widespread irrigated agriculture along the base of the mountains and in river basins, especially along the Tigris and Euphrates. Nomadic herders living in adjacent grasslands traded animal products for the grain and other goods produced in the settled areas.

Over several thousand years, agriculture spread to the Nile Valley, west across North Africa, north and west into Europe, and east to the mountains of Persia (modern Iran). Ultimately, other cultivation systems across the world were influenced by developments in the Fertile Crescent. Eventually, small settlements associated with agriculture took on urban qualities: dense populations, specialized occupations, concentrations of wealth, and centralized government and bureaucracies. For example, the agricultural villages of Sumer (in modern southern Iraq), which existed 5000 years ago, gradually turned into city-states that extended their influence over the surrounding territory. The Sumerians developed wheeled vehicles, oar-driven ships, and irrigation technology.

From time to time, nomadic tribes who had adopted the horse as a means of conquest banded together and, with devastating cavalry raids, swept over agricultural settlements. They then set themselves up as a ruling class, but soon these former nomads adopted the settled ways and cultures of the peoples they conquered and thus themselves became vulnerable to attack.

Agriculture and Gender Roles

Increasing research evidence suggests that the dawning of agriculture may have marked the transition to markedly distinct roles for men and women. Archaeologist Ian Hodder reports that at the 9000-year-old site of Catalhöyük (see Figure 6.12), near modern Konya in south-central Turkey, where the economy was primarily hunting and gathering, there is little evidence of gender differences. Families were small and men and women performed similar chores in daily life. Both had comparable status and power, and both played key roles in social and religious life. Archaeological evidence elsewhere indicates that gender roles were also egalitarian in other pre-agricultural societies.

Scholars think that after the development of agriculture, as the accumulation of wealth and property became more important in human society, concerns about family lines of descent and inheritance emerged. This led in turn to the idea that women’s bodies needed to be controlled so that a woman could not become pregnant by a man other than her mate and thus confuse lines of inheritance. From this core concern about secure lines of descent grew many practices aimed at reinforcing the idea that the mating of women had to be controlled, and by extension, that women’s daily spatial freedom, interaction with men, and sexuality needed to be curtailed.

The Coming of Monotheism: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

monotheism the belief that there is only one god

Judaism a monotheistic religion characterized by the belief in one god (Yahweh), a strong ethical code summarized in the Ten Commandments, and an enduring ethnic identity

diaspora the dispersion of Jews around the globe after they were expelled from the eastern Mediterranean by the Roman Empire, beginning in 73 c.e.; the term can now refer to other dispersed culture groups

Christianity a monotheistic religion based on the belief in the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew, who described God’s relationship to humans as primarily one of love and support, as exemplified by the Ten Commandments

After Jesus’s execution in Jerusalem in about 32 c.e., his teachings were written down (the Gospels) by those who followed him, and his ideas as interpreted by these writers spread and became known as Christianity. Centuries of persecution ensued, but by 400 c.e., Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire. However, following the spread of Islam after 622 c.e., only remnants of Christianity remained in Southwest Asia and North Africa.

Muslims followers of Islam

Unlike the many versions of Christianity, Islam has virtually no central administration and only an informal religious hierarchy (this is somewhat less true of the Shi’ite version of Islam; see the discussion). The world’s 1 billion Muslims may communicate directly with God (Allah). A clerical intermediary is not necessary, though there are numerous clerical leaders who help their followers interpret the Qur’an. An important result of the lack of a central authority is that the interpretation of Islam varies widely within and among countries, from group to group, and from individual to individual.

The Spread of Islam

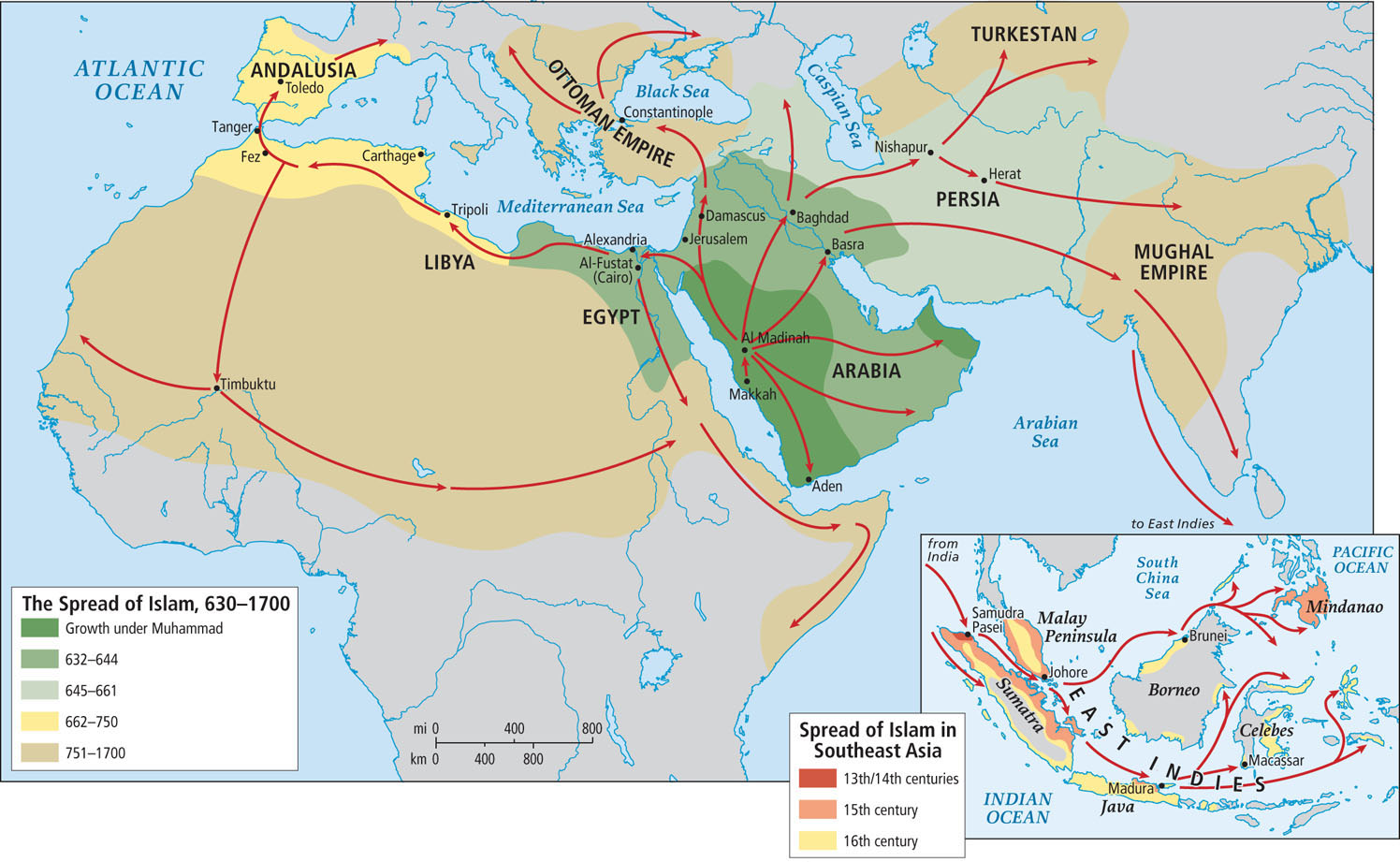

Among the first converts to Islam were the Bedouin—nomads of the Arabian Peninsula. By the time of Muhammad’s death in 632 c.e., they were already spreading the faith and creating a vast Islamic sphere of influence. Over the next century, Muslim armies built an Arab-Islamic empire over most of Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula of Europe (Figure 6.14).

While most of Europe was stagnating during the medieval period (450–1500 c.e.), the Arab-Islamic empire nurtured learning and economic development. Muslim scholars traveled throughout Asia and Africa, advancing the fields of architecture, history, mathematics, geography, and medicine. Centers of learning flourished from Baghdad (Iraq) to Toledo (Spain). During the early Arab-Islamic era, the development of banks, trusts, checks, receipts, and bookkeeping fostered vibrant economies and wideranging trade. The traders founded settlements and introduced new forms of living spaces. The architectural legacy of Arabs and Muslims lives on in Spain, India, Central Asia, the Americas, and in countless buildings across the world (see Figure 6.18).

Ottoman Empire the most influential Islamic empire the world has ever known; begun in the 1200s when nomadic Turkic herders from Central Asia converged in western Anatolia (Turkey)

By the 1300s, the Ottomans had become Muslim, and by the 1400s they had defeated the Christian Byzantine Empire, centered in Constantinople, which was the successor to the Roman Empire. The Ottomans took over Constantinople, renamed it Istanbul, and soon controlled most of the eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. By the late 1400s, they also controlled much of southeastern and central Europe and by the 1600s had taken over parts of coastal North Africa from the Arabs. Previously, in the 1490s, the Arab Muslims had lost their control of the Iberian Peninsula to Christian kingdoms. Today, Islam still dominates in a huge area that stretches from Morocco to western China and includes northern South Asia, as well as Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia in Southeast Asia (see the inset of Figure 6.14).

Once a location was completely conquered, the Ottoman Empire, like the Arab-Islamic empire before it, encouraged religious tolerance toward the conquered peoples so long as they adhered to a religion with a sacred text. Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and Zoroastrians were allowed to practice their religions, although there were attractive economic and social advantages to converting to Islam. Multicultural urban life in Ottoman cities facilitated vast trading networks spanning the known world, and Istanbul became a cosmopolitan capital with elaborate buildings and lavish public parks that outshined anything in Europe until the nineteenth century (see Figure 6.15C).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of North Africa and Southwest Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What allowed for urban settlements like Harran to develop?

What allowed for urban settlements like Harran to develop?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What ceremonial purpose is filled by the Masjid-Al-Haram and the Kaaba in Makkah?

What ceremonial purpose is filled by the Masjid-Al-Haram and the Kaaba in Makkah?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What Turkish city had lavish buildings and parks that outshined anything in Europe until the nineteenth century?

What Turkish city had lavish buildings and parks that outshined anything in Europe until the nineteenth century?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

When did France first assert control over the territory in what is now Algeria?

When did France first assert control over the territory in what is now Algeria?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

The state of Israel was formally created in the aftermath of what event in Europe?

The state of Israel was formally created in the aftermath of what event in Europe?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why did European and U.S. companies become involved in deciding who ruled Iran and Saudi Arabia?

Why did European and U.S. companies become involved in deciding who ruled Iran and Saudi Arabia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Western Domination, State Formation, and Antidemocratic Practices

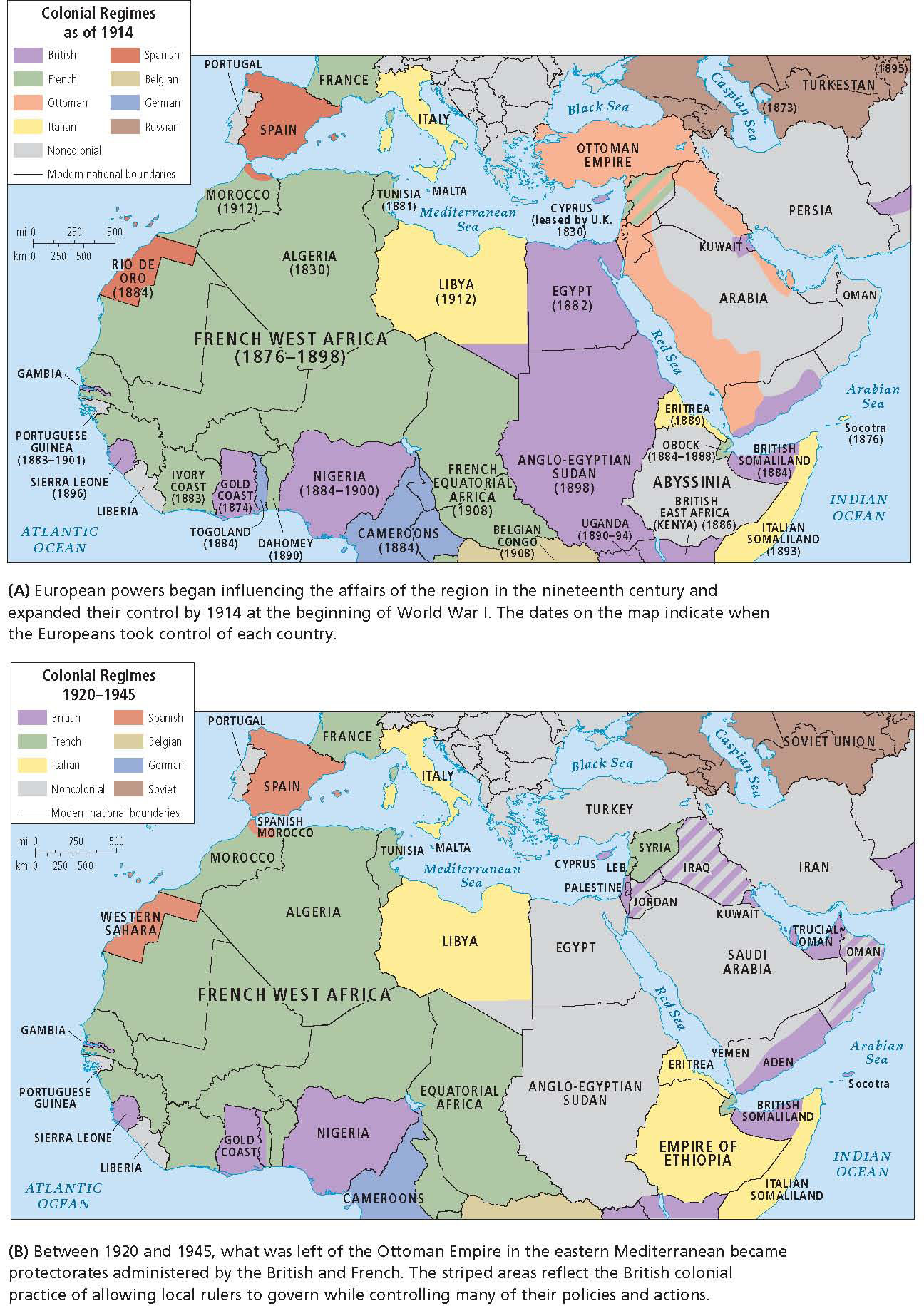

The Ottoman Empire ultimately withered in the face of a Europe made powerful by colonialism and the Industrial Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth century, North Africa provided raw materials for Europe in a trading relationship dominated by European merchants. By 1830, France was exercising direct control over parts of the North African territory of Algeria (see Figure 6.15D). France took control of Tunisia in 1881 and Morocco in 1912 (Spain controlled a bit of the Mediterranean coast and what is now called Western Sahara); Britain gained control of Egypt in 1882 and Sudan in 1898; and Italy took control of Libya in 1912 (Figure 6.16A).

World War I (1914–1918) brought the fall of the Ottoman Empire, which had allied itself with Germany. At the end of the war, the victorious powers dismantled the Ottoman Empire and all of the former Ottoman territories; only Turkey was recognized as an independent country. The rest of the formerly Ottoman-controlled territory was allotted to France and Britain as protectorates (see Figure 6.16B). On the Arabian Peninsula, Bedouin tribes were consolidated under Sheikh Ibn Saud in 1932, and Saudi Arabia began to emerge as an independent country.

World War II (1939–1945) further affected the political development of North Africa and Southwest Asia. Most significantly, in the aftermath of the Holocaust in Europe, the Jewish state of Israel was created in the eastern Mediterranean on land inhabited by Arab farmers and nomadic herders as well as by some Jews (see the discussion; see also Figure 6.15E).

By the 1950s, European and U.S. energy companies played a key role in influencing who ruled Iran and Saudi Arabia—countries where vast oil deposits were to become especially lucrative. In Egypt, a major cotton producer, European textile companies played a similar role. Officials in the governments of these countries received financial benefits from foreign companies and showed their loyalty to these companies with low taxes on oil and cotton exports and easy access to land. While a tiny ruling elite grew fabulously wealthy, even the modest oil and other tax revenues were not invested in creating opportunities for the vast majority of poor people. Over time, ever more political power accrued, especially to foreign energy companies. The United States and Western Europe supported those autocratic local leaders who were most sympathetic to the interests of their companies and their Cold War strategies vis-à-vis the Soviet Union (see Figure 6.15F). As a result of these concerns, both the Europeans and the Americans supported undemocratic governments and stood in the way of reforms that would have resulted in a more educated populace able to participate in the full range of democratic institutions.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

About 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, formerly nomadic peoples founded some of the world’s earliest known agricultural communities. The domestication of plants and animals allowed them to build ever more elaborate settlements that eventually grew into societies based on widespread irrigated agriculture.

About 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, formerly nomadic peoples founded some of the world’s earliest known agricultural communities. The domestication of plants and animals allowed them to build ever more elaborate settlements that eventually grew into societies based on widespread irrigated agriculture. The three major monotheistic world religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all have their origins in this region in the eastern Mediterranean. In the region, Islam is by far the largest in numbers of adherents, and it is the principal faith in all of the region’s countries except Israel.

The three major monotheistic world religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all have their origins in this region in the eastern Mediterranean. In the region, Islam is by far the largest in numbers of adherents, and it is the principal faith in all of the region’s countries except Israel. Beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing through the end of World War II, European colonial powers ruled or controlled most countries in the region.

Beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing through the end of World War II, European colonial powers ruled or controlled most countries in the region. Following World War II, the state of Israel was created, and in countries with oil deposits and other useful assets, the United States and Western Europe supported those autocratic local leaders most likely to maintain a friendly attitude toward U.S. and European business and geopolitical strategic interests.

Following World War II, the state of Israel was created, and in countries with oil deposits and other useful assets, the United States and Western Europe supported those autocratic local leaders most likely to maintain a friendly attitude toward U.S. and European business and geopolitical strategic interests.