Sociocultural Issues

This section explores the basics of the pervasive influence of Islam on the culture of the region and examines the broad social changes occurring with regard to family values, gender roles and gendered spaces, demographic change, urbanization and migration, and patterns of human well-being.

Religion in Daily Life

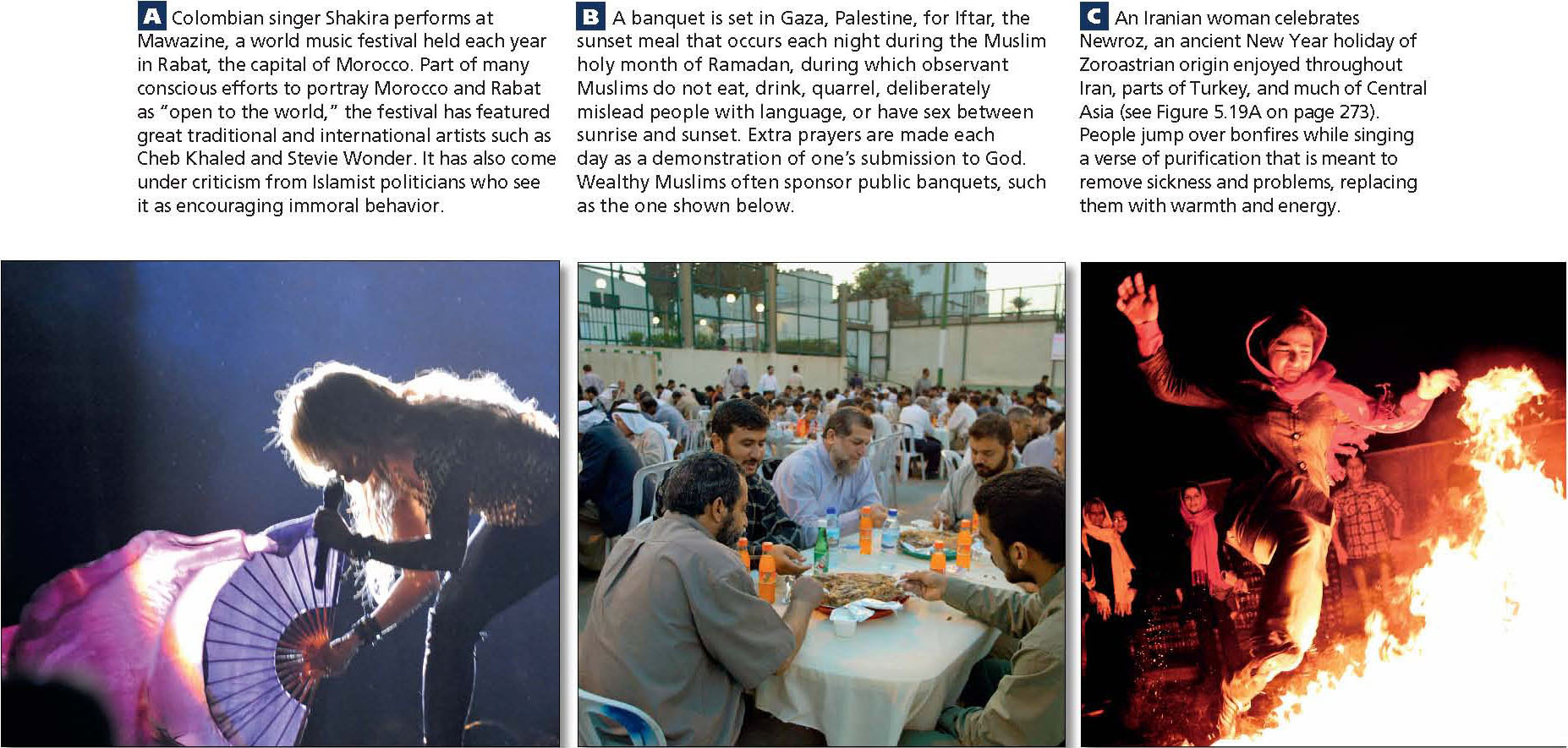

Ninety-three percent of the people in the region are followers of Islam; for them, the Five Pillars of Islamic Practice embody the central teachings of Islam. Not all Muslims are fully observant, but the Pillars have an impact on daily life, including festivals and religious holidays (Figure 6.17).

The Pillars of Muslim Practice

- 1. A testimony of belief in Allah as the only God and in Muhammad as his messenger (prophet).

- 2. Daily prayer at five designated times (daybreak, noon, midafternoon, sunset, and evening). Although prayer is an individual activity, Muslims are encouraged to pray in groups and in mosques. The call to prayer, broadcast five times a day in all parts of the region, is a constant reminder to all people to reflect on their beliefs.

- 3. Obligatory fasting (no food, drink, or smoking) during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan, followed by a light celebratory family meal after sundown. Ramadan falls in the ninth month of the Islamic (lunar) calendar.

- 4. Obligatory almsgiving (zakat) in the form of a “tax” of at least 2.5 percent. The alms are given to Muslims in need. Zakat is based on the recognition of the injustice of economic inequity. Although it is usually an individual act, the practice of government-enforced zakat is returning in certain Islamic republics.

- 5. Pilgrimage (hajj) at least once in a lifetime to the Islamic holy places, especially the Masjid Al-Haram and the Kaaba in Makkah (Mecca), during the twelfth month of the Islamic calendar.

hajj the pilgrimage to the city of Makkah (Mecca) that all Muslims are encouraged to undertake at least once in a lifetime

Saudi Arabia occupies a prestigious position in Islam, as it is the site of two of Islam’s three holy shrines: Makkah, the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad and of Islam; and Al Madinah (Medina), the site of the Prophet’s mosque and his burial place. (The third holy shrine is in Jerusalem.) The fifth pillar of Islam has placed Makkah and Al Madinah at the heart of Muslim religious geography. Each year, a large private sector service industry, owned and managed by members of the huge Saud family, organizes and oversees the 5- to 7-day hajj for more than 2.5 million devout foreign visitors.

Islamic Religious Law and Variable Interpretations

shari’a literally, “the correct path”; Islamic religious law that guides daily life according to the interpretations of the Qur’an

Sunni the larger of two major groups of Muslims who have different interpretations of shari’a

Shi’ite (or Shi’a) the smaller of two major groups of Muslims who have different interpretations of shari’a; Shi’ites are found primarily in Iran and southern Iraq

The Sunni-Shi’ite split dates from shortly after the death of Muhammad, when divisions arose over who should succeed the Prophet and have the right to interpret the Qur’an for all Muslims. This division continues today. The original disagreements have been exacerbated by countless local disputes over land, resources, and philosophies. In Iraq, for example, long-standing conflict between Sunnis and Shi’ites intensified following the U.S. invasion in 2003, as rivalries arose over which group should control political power and fossil fuel resources.

Family Values and Gender

In part because Islam has so little religious hierarchy, the family is the most important institution in this region. Although the role of the family is changing, a person’s family is still such a large component of personal identity that the idea of individuality is almost a foreign concept. Each person is first and foremost part of a family, and the defining parameter of one’s role in the family is gender identity.

patriarchal relating to a social organization in which the father is supreme in the clan or family

Gender Roles and Gendered Spaces

Carefully specified gender roles are common in many cultures, and there is often a spatial component to these roles. In the region of North Africa and Southwest Asia, in both rural and urban settings, the ideal is for men and boys to go forth into public spaces—the town square, shops, the market. Women are expected to inhabit primarily private spaces. But there are many possible exceptions to those ideals.

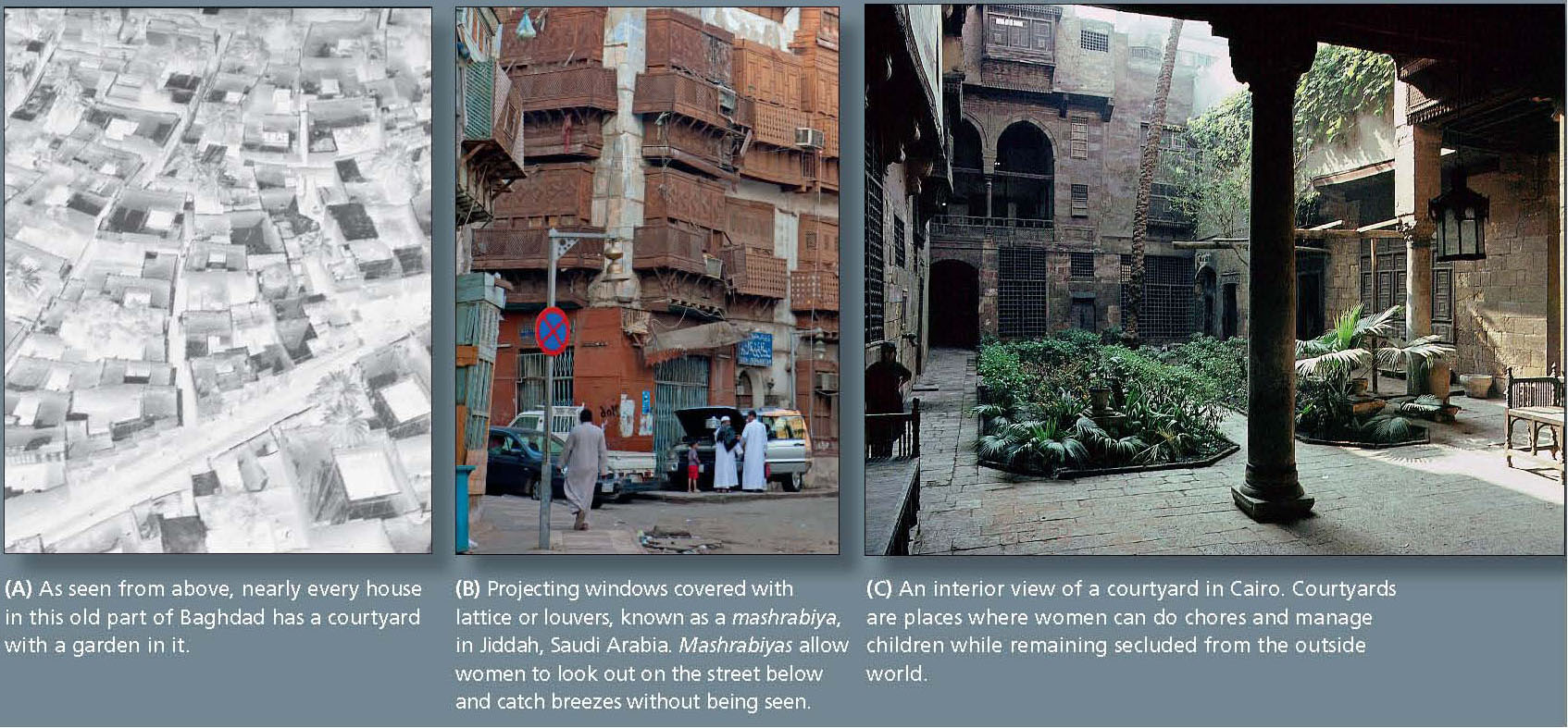

To facilitate this ideal of public/private spaces for the sexes, traditional family compounds included a courtyard that was usually a private, female space within the home (Figure 6.18A, C); the only men who could enter it were relatives. For the urban upper classes, female space was an upstairs set of rooms with latticework or shutters at the windows, which increased the interior ventilation and from which it was possible to look out at street life without being seen (see Figure 6.18B). Today, the majority of people in the region live in urban apartments, yet even in these there is a demarcation of public and private space. One or two formally furnished reception areas are reserved for nonfamily visitors, and rooms deeper into the dwelling are for family-only activities. When guests are present, women in the family are usually absent or present only briefly. Customs vary not only from country to country but also from rural to urban settings, by social class, and by personal preference. Today, many women as well as men go out into public spaces, but the conditions under which women enter these spaces remain an issue and a woman who challenges convention does so at her own peril and that of her family’s reputation.

female seclusion the requirement that women stay out of public view

Gulf states Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates

jihadists especially militant Islamists

veil the custom of covering the body with a loose dress and/or of covering the head—and in some places the face—with a scarf

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do these women choose to wear a veil (regardless of the style of veil they wear)?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

There is considerable debate about the origin and validity of female seclusion and whether veiling and seclusion are specifically Muslim customs. Scholars say that these ideas, as well as the custom of having more than one wife, actually predate Islam by thousands of years and do not derive from the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. In fact, Muhammad may have been reacting against such customs when he advocated equal treatment of males and females. Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija, did not practice seclusion and worked as an independent businesswoman whose counsel Muhammad often sought.  146. EDUCATION, ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT ARE KEYS TO BETTER LIFE FOR MUSLIM WOMEN

146. EDUCATION, ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT ARE KEYS TO BETTER LIFE FOR MUSLIM WOMEN

The Rights of Women in Islam

This region has notably more restrictive customary and legal limits on women than any other. In some Gulf states, women cannot travel independently or even drive a car or shop without male supervision. Yet even here changes have recently been made. In the decade of the 2000s, some women in the Gulf states became more active in public life, education, and business. In Qatar, Sheikha Moza, the second of the three wives of the emir (Muslim ruler) of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, has implemented remarkable changes for women. They can now drive, attend university, be elected to political office, and work side by side with men; the sheikha has founded a battered women’s shelter and serves as a UNESCO envoy. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a few female activists, along with other female lawyers and journalists, have begun to question persistent patriarchal attitudes. Saudi Arabia remains the most restrictive country, but even there it is now possible for a woman to register a business without first proving that she has hired a male manager. A few young Saudi women even staged mini-demonstrations by posting on YouTube videos of themselves driving. Although they were eventually punished by the state for this behavior, they inspired further challenges to convention.

The Arab Spring in North Africa demonstrated just how elusive political equality for women can be. In Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, some women were active as public protesters against undemocratic regimes, but military and civilian supporters of the various regimes singled them out for particularly harsh retribution. Among their fellow male demonstrators, it was usually the younger men who supported the women’s rights and physically defended them when supporters of the various regimes attacked.

A practice that is a source of contention within this region and abroad is polygyny (see Chapter 7)—the taking by a man of more than one wife at a time. Although the Qur’an allows a man up to four wives, it generally does not encourage this and imposes financial limits on the practice by requiring that each wife be given separate and equal living quarters and support. While legal in most of the region (not Tunisia), polygyny is relatively rare, with less than 4 percent of males in North Africa practicing it. In Southwest Asia, polygyny—not covered in any reliable statistical surveys, but only in secondary reports—may be somewhat more common. About 5 percent in Jordan and 8 to 12 percent of marriages in Kuwait are polygamous. The social justifications given for polygyny further illustrate traditional ideas about women’s rights in Islam. In common legal practice in many countries, an unmarried woman under 40 must be regarded as a minor requiring protection. Therefore, if a man takes her as a second or third wife, she gains support and safety. Similarly, a widow is saved from disgrace and poverty if her dead husband’s brother takes her as an additional wife.

Female genital mutilation (FGM, defined and discussed in Chapter 7) is not widely practiced in this region except in Egypt, where although it is illegal, as of 2013 according to the World Health Organization, more than 90 percent of women have undergone the practice, mostly before age 15.

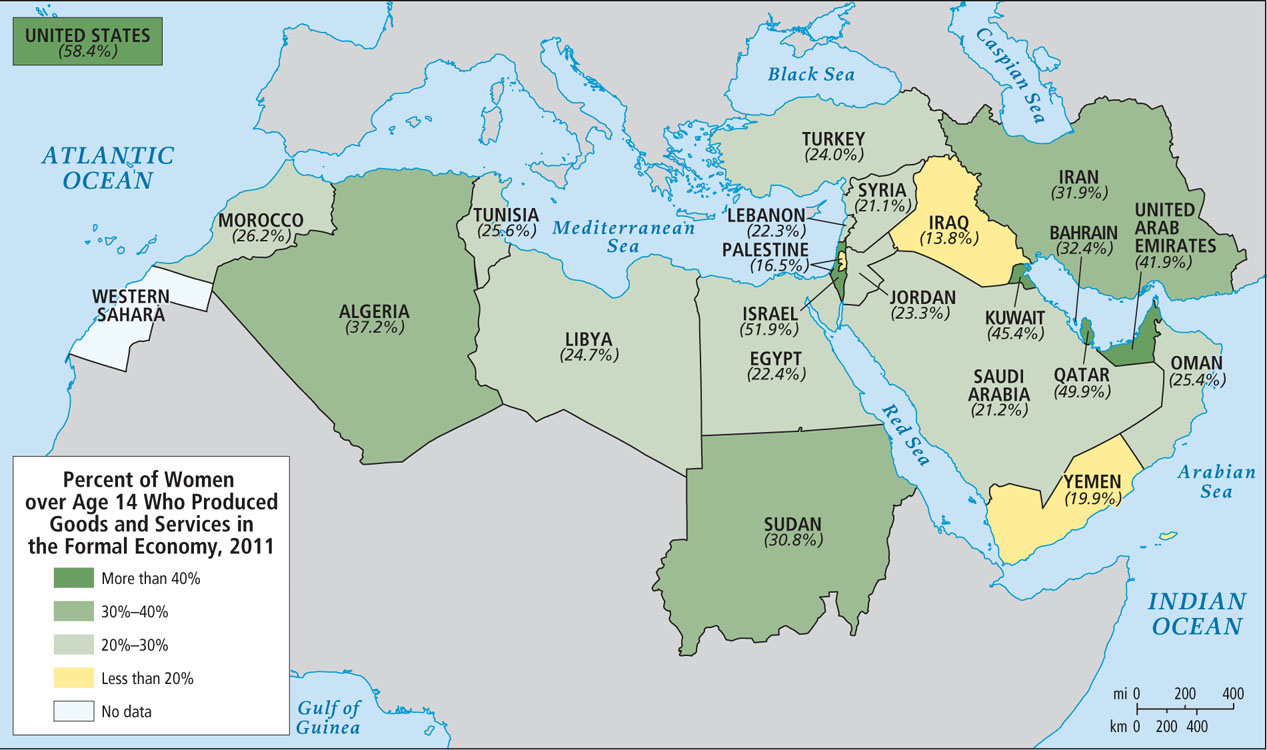

Political and social equality with men can only improve with more economic independence for women (Figure 6.20). With the sole exception of Israel, women in this region generally do not work outside the home; when they do, they are paid, on average, only about 40 percent of what men earn for comparable work (see Figure 6.24C). Only India, Pakistan, and other South Asian countries have a similarly large wage gap based on gender.

The Lives of Children

Three sweeping statements can be made about the lives of children in the Islamic cultures of North Africa and Southwest Asia. First, in most families children contribute to the welfare of the family starting at a very young age. In cities, they run errands, clean the family compound, and care for younger siblings. In rural areas, they do all these chores and also tend grazing animals, fetch water, and tend gardens. Second, their daily lives take place overwhelmingly within the family circle. Both girls and boys spend their time within the family compound or in urban areas in adjacent family apartments. Their companions are adult female relatives and siblings and cousins of both sexes. Even teenage boys in most parts of the region identify more with family than with age peers.

In rural areas, prepubescent girls can move about in public space as they go about their chores in the village. After puberty they may be restricted to the family compound and required to wear the veil. The U.S. geographer Cindi Katz found that until puberty, rural Sudanese Muslim girls have considerably more spatial freedom than do girls of similar ages in the United States, who are rarely allowed to range alone through their own neighborhoods.

The third observation is that school, television, and the Internet increasingly influence the lives of children and introduce them to a wider world. Most children go to school; many boys go for a decade or more, and increasingly girls go for more than a few years. In some countries (Algeria, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, the occupied Palestinian Territories, Oman, Qatar, Tunisia, and the UAE), a larger percentage of girls than boys go to school. Like educated women everywhere, these girls will make life choices different from those of their mothers.

Even in rural areas, it is fairly common for the poorest families to have access to a television, which is often on all day, in part because it provides a window to the world for secluded women. Television can serve either to reinforce traditional cultural values or as a vehicle for secular perspectives, depending on which channels are watched.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

For Muslims (93 percent of the population in this region), the Five Pillars of Islamic Practice embody the central teachings of Islam. Some Muslims are fully observant, some are not; but the Pillars have an impact on daily life for all. The call to prayer, broadcast five times a day in all parts of the region, is a reminder to all people to reflect on their beliefs.

For Muslims (93 percent of the population in this region), the Five Pillars of Islamic Practice embody the central teachings of Islam. Some Muslims are fully observant, some are not; but the Pillars have an impact on daily life for all. The call to prayer, broadcast five times a day in all parts of the region, is a reminder to all people to reflect on their beliefs. Given the wide diversity of thought, beliefs, and practices of Islam, the family is probably the most important societal institution for Muslims in the region.

Given the wide diversity of thought, beliefs, and practices of Islam, the family is probably the most important societal institution for Muslims in the region. Most Muslim families in this region are patriarchal in structure; and the role and status of women, the spaces they occupy, and sometimes even the clothes they wear are carefully defined, circumscribed, and in some cases rigidly imposed.

Most Muslim families in this region are patriarchal in structure; and the role and status of women, the spaces they occupy, and sometimes even the clothes they wear are carefully defined, circumscribed, and in some cases rigidly imposed.

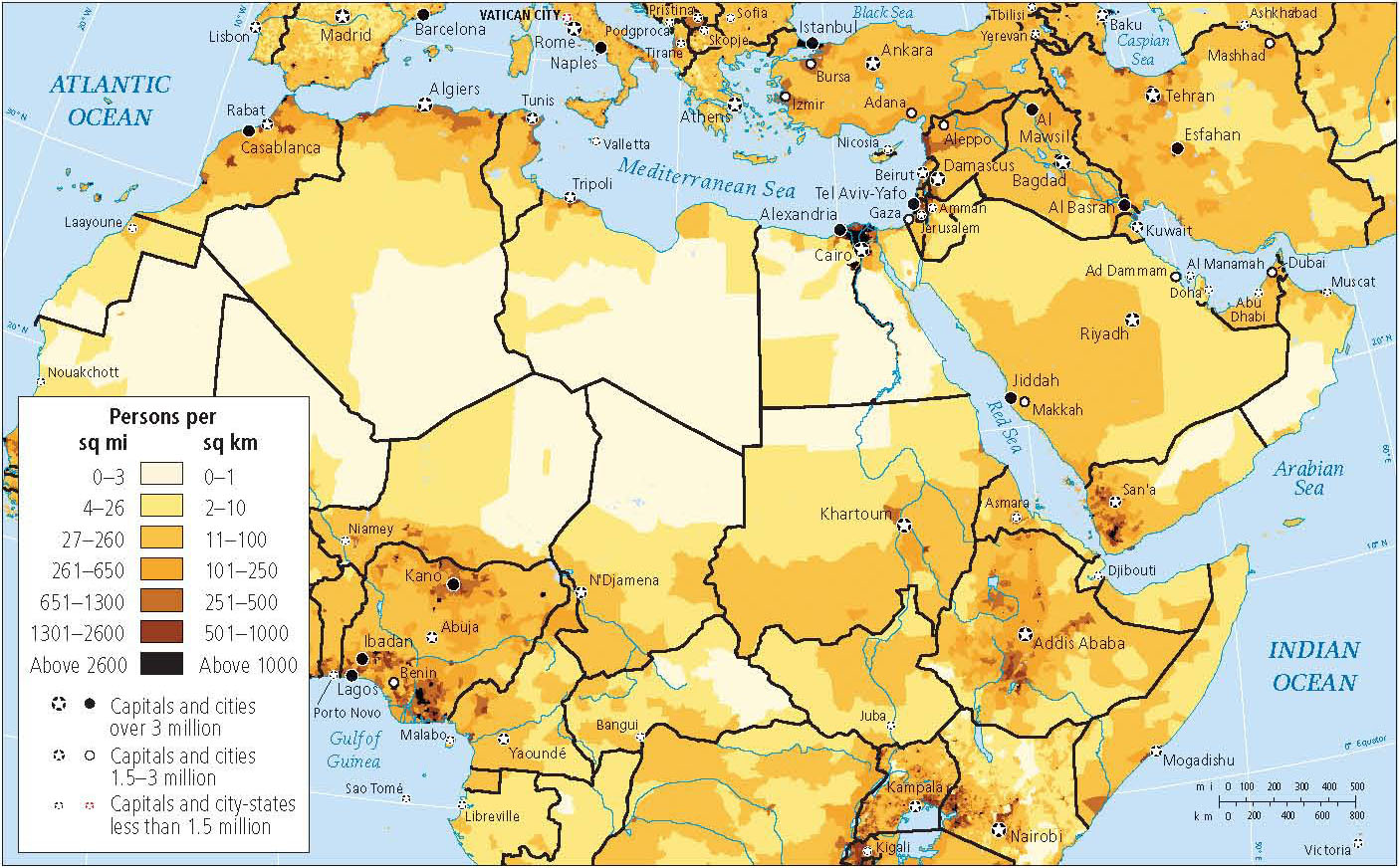

Changing Population Patterns

Although the region as a whole is nearly twice as large as the United States, most of the population is concentrated in the few areas that are useful for agriculture. Vast tracts of desert are virtually uninhabited, while the region’s 477 million people are packed into coastal zones, river valleys, and mountainous areas that capture orographic rainfall (compare Figure 6.21 with Figure 6.5). Population densities in these areas can be quite high. For example, some of Egypt’s urban neighborhoods have over 260,000 people per square mile (100,000 people per square kilometer), a density 4 times higher than that of New York City, the densest city in the United States.

Population Growth and Gender Status

Geographic Insight 2

Gender and Population: Gender disparities are increasingly prominent in this region as political change begins to occur. Women are dependent because they are generally less educated than men, have few options for working outside the home, and have little access to political power. Women’s roles are usually confined to the home and to having and raising children. As a result, this region has the second-highest population growth rate in the world, after sub-Saharan Africa.

Although fertility rates have dropped significantly since the 1960s, to 3.1 children per adult woman in 2012, they are still higher than the world average of 2.6. Only sub-Saharan Africa, at 5.1 children per woman, is growing faster. At current growth rates, the population of the region will be about 540 million by 2025. This growth will severely strain supplies of fresh water and food and will worsen shortages of housing, jobs, medical care, and education.

As noted in many world regions, population growth rates are higher in societies where women are not accorded basic human rights, are less educated, and work primarily inside the home. In places where women have opportunities to work or study outside the home, they usually choose to have fewer children. Figure 6.20 shows that as of 2011, considerably less than 50 percent of women across the region (except in Israel, Kuwait, and Qatar) worked outside the home at jobs other than farming. Moreover, on average only 74.8 percent of adult females can read—a fact that limits their employability—whereas 88 percent of adult males can read.

For uneducated women who work only at home or in family agricultural plots, children remain the most important source of personal fulfillment, family involvement, and power. This may partially explain why in 2011 a good deal less than half of women in this region were using modern methods of contraception, and only 54 percent were using any method of contraception at all. Both of these numbers are well below the world average of 55 and 62 percent, respectively. Other factors resulting in low use of contraception are male dominance over reproductive decisions and the unavailability or high cost of effective birth control products.

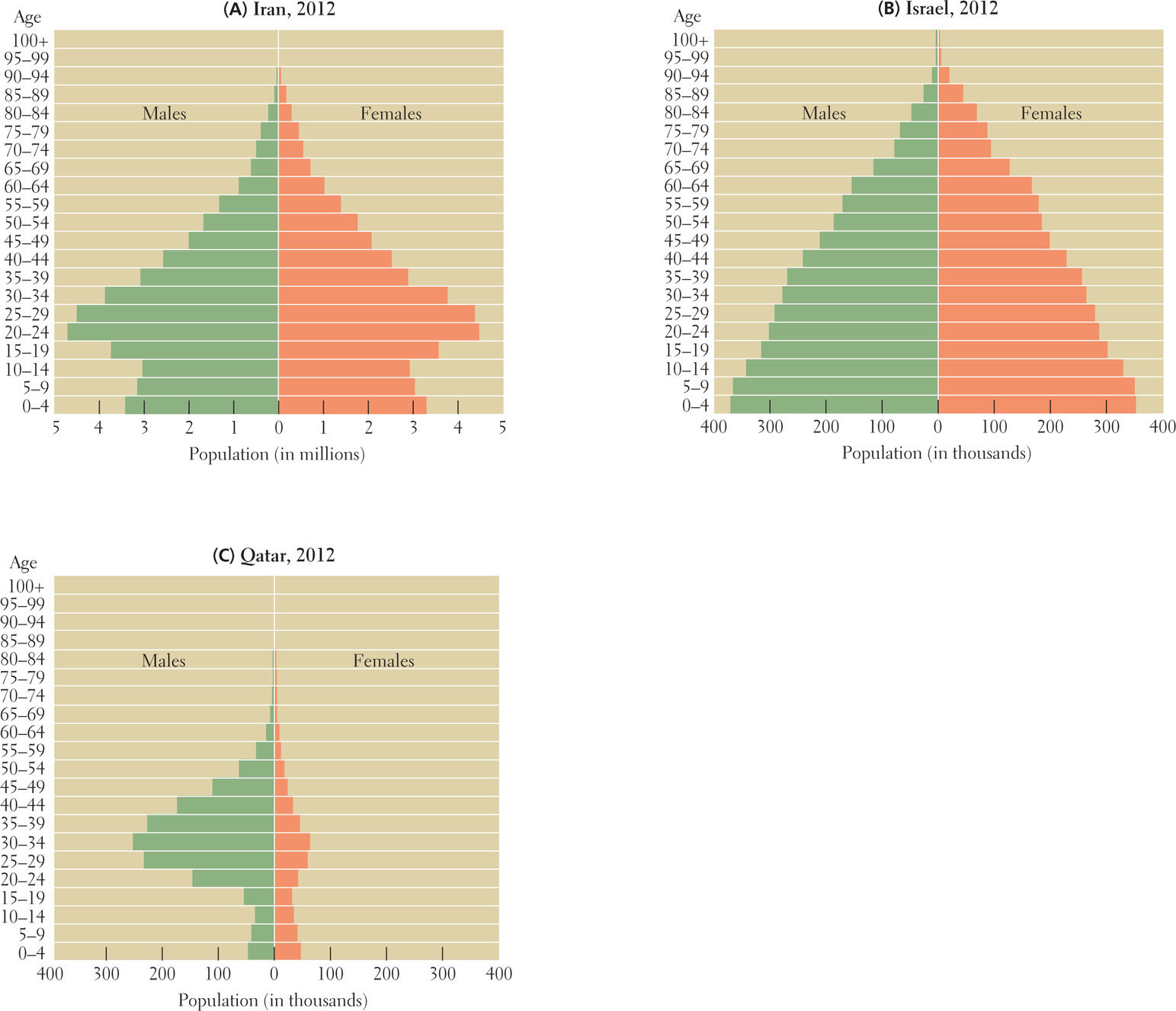

The deeply entrenched cultural preference for sons in this region is both a cause and a result of women’s lower social and economic standing. It also contributes to population growth, as families sometimes continue having children until they have a desired number of sons. Moreover, some young females may not survive because of malnutrition and associated illnesses or because female fetuses are sometimes aborted. The result is that males slightly outnumber females in several age cohorts of the population pyramids in Figure 6.22 (see also the discussion in Chapter 1). In Qatar and the UAE, gender imbalance is extreme (see Figure 6.22C); in these countries, the unusually large numbers of males over the age of 15 is the result of the presence of numerous male guest workers. Opportunities for women are opening and this change is likely to reduce women’s interest in having large families. Slower population growth will mean that fewer resources will have to be invested in housing, schools, and services (see “On the Bright Side”).

Urbanization, Globalization, and Migration

Geographic Insight 3

Urbanization and Globalization: Two patterns of urbanization have emerged in the region, both tied to the global economy. In the oil-rich countries, the development of spectacular new luxury-oriented urban areas is based on flows of money, credit, goods, and skilled people. But most cities are old, with little capacity to handle the mass of poor, rural migrants attracted by export industries aimed at earning foreign currency. In these older cities, many people live in overcrowded slums with few services.

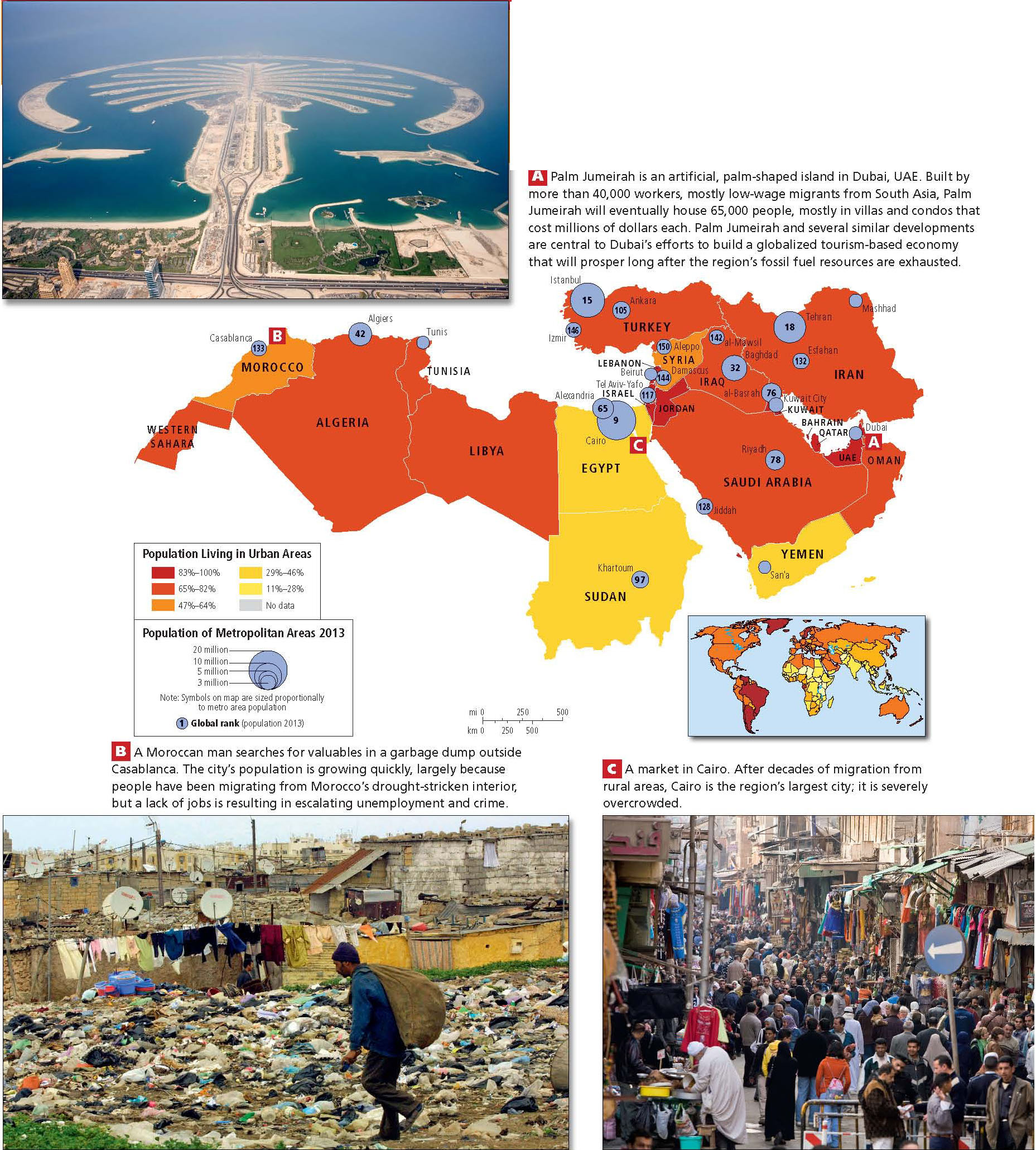

Urbanization is transforming this region. Two highly globalized patterns of urbanization with distinct geographic signatures are now apparent: one pattern in the newly oil-rich countries, and another in those countries where development has primarily resulted in rural-to-urban migration with associated crowded slum housing.

Until the 1970s, most people lived in small rural settlements. Then, however, significant migration from villages to urban areas began to occur in response to economic forces driven by oil wealth and globalization, and by agricultural modernization that displaced small farmers. In locations other than the Gulf states, the shift toward green revolution-style export-oriented agriculture reduced the labor needed to produce crops headed for the world market. Even though the green revolution promoted needed export income for the countries, people who became part of the excess labor force had to leave the countryside for the cities. In North Africa, drought also instigated rural-to-urban migration (Figure 6.23B). By 2008, more than 70 percent of the region’s people lived in urban areas (the definition of urban varies by country; see the Figure 6.23 map). By 2009, there were more than 434 cities with populations of at least 100,000 and 37 cities with more than 1 million people. The largest metropolitan area in the region, and one of the largest in the world, is Cairo, with 17 million residents in 2012.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in North Africa and Southwest Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What circumstances dealt a blow to high-end technology and tourism development in the Gulf states, such as Dubai?

What circumstances dealt a blow to high-end technology and tourism development in the Gulf states, such as Dubai?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

By 2008, what percent of the population in this region lived in urban areas?

By 2008, what percent of the population in this region lived in urban areas?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What has driven the migration of rural people to the region's old established cities, such as Cairo?

What has driven the migration of rural people to the region's old established cities, such as Cairo?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

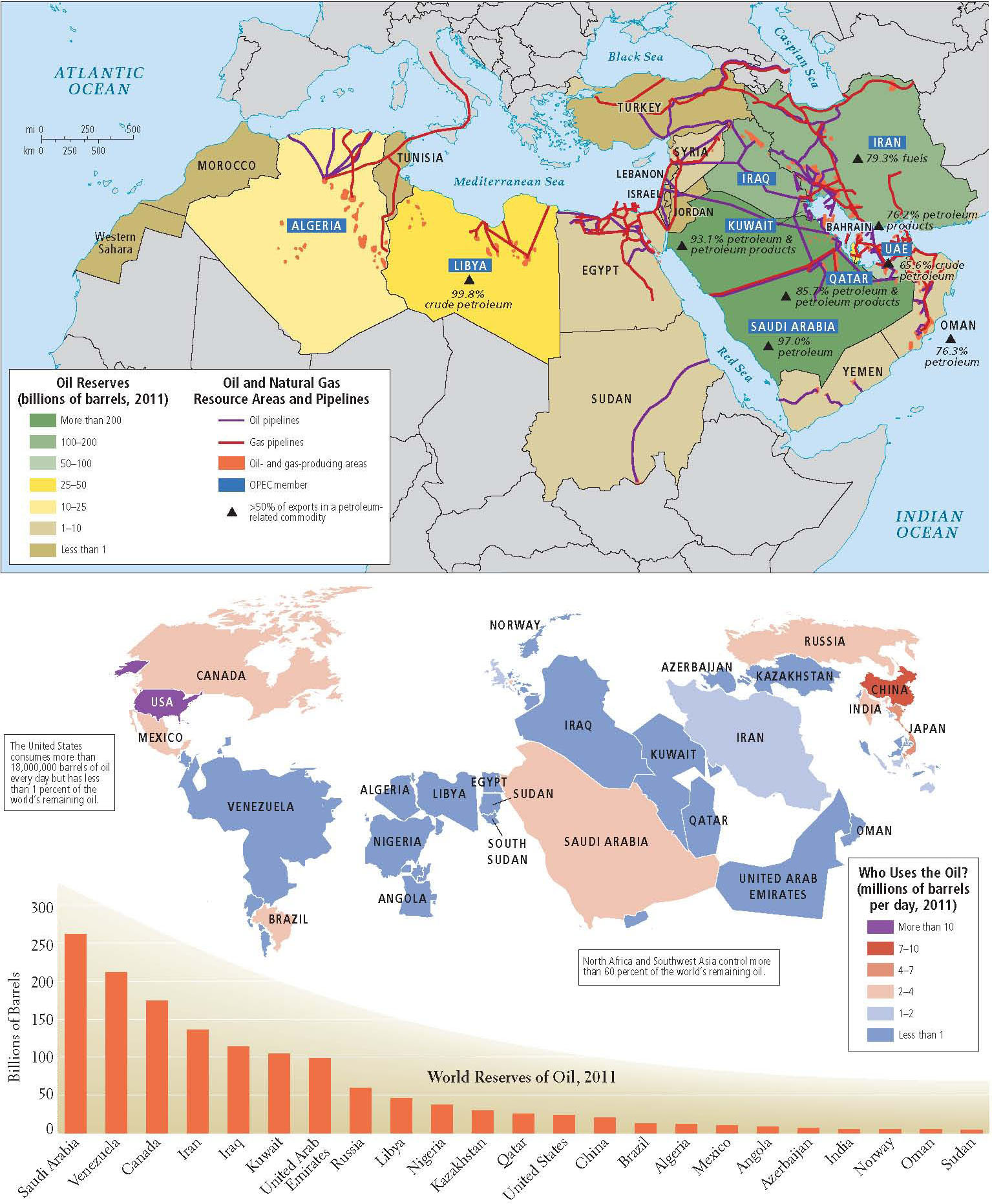

The petroleum-rich Gulf states are now highly urbanized. Between 70 and 100 percent of the (still small) population now lives in urban areas, which are extravagant in design. These modern Gulf cities draw investment in high-tech ventures and high-end tourism. The new ventures and the construction of office and living space require a wide range of skilled workers from all over the world. For example, Dubai (one of the United Arab Emirates) has built elaborate (and as yet largely unoccupied) new high-rise condominiums for the rich. On Palm Jumeirah, a fanciful palm tree-shaped island and peninsula off the Gulf coastline, huge homes await buyers (see Figure 6.23A). The unexpectedly slow “take off” for the new Gulf cities is in large part the result of the global recession that began in 2008 and continues. The wealthier emirates subsidize the living standards of their citizens with oil profits, and for the most part only foreign contract laborers have low standards of living.

Outside the Gulf states, urban growth has been planned and financed far less well. For example, in 1950, Cairo had about 2.4 million residents, while today it is home to over 17 million people. These millions of new residents live in huge makeshift slums. Meanwhile, much of Cairo’s middle class occupies the medieval interiors of the old city, where streets are narrow pedestrian pathways and plumbing and other services are chronically dysfunctional (see Figure 6.23C).

Internal and International Migration

The prospect of better education opportunities, jobs, and living conditions pull rural internal migrants into Cairo and other cities outside the Gulf states. However, because stable well-paying jobs are scarce, many migrants end up working in the informal economy (see Chapter 3), sometimes as street vendors, as casual laborers, or as menial service providers. Unfortunately, education also does little to ensure employment; for decades this region has been noted for the large numbers of unemployed and underemployed university graduates.

In the Gulf states, on the other hand, there has been a deficit of trained native young people willing and able to work in white-collar jobs, yet surplus trained workers from neighboring countries have not been welcomed. Instead, immigrants come from all over the world to be temporary guest workers. Some work as laborers on construction sites and as low-wage workers throughout the service economy, but many work in shops and professions. In some countries, such as the UAE, guest workers make up 85 percent of the labor force. Most employers prefer Muslim guest workers, and over the last two decades, several hundred thousand Muslim workers have arrived from Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Syria, as well as from Egypt, Pakistan, and India. Some female domestic and clerical workers come from Muslim countries in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines. Overwhelmingly, these immigrant workers are temporary residents with no job security and no right to become citizens. They remit most of their income to their families at home and often live in stark conditions alongside the opulence of those enriched by oil and gas (see discussion in Chapter 10).

Refugees comprise another category of migrants. This region has the largest number of refugees in the world. Usually they are escaping human conflict, but environmental disasters such as earthquakes or long-term drought also displace many people. When Israel was created in 1949, many Palestinians were placed in refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Palestinians still constitute the world’s oldest and largest refugee population, numbering at least 5 million. Elsewhere, Iran is sheltering more than a million Afghans and Iraqis because of continuing violence and instability in their home countries. Across the region, even more people are refugees within their own countries: 1.7 million Iraqis are internal refugees, and in Sudan, about 2.3 million internal refugees are living in camps. The conflict against the Assad regime in Syria has recently produced several million internal and external refugees.

Refugee camps often become semipermanent communities of stateless people in which whole generations are born, mature, and die. Although residents of these camps can show enormous ingenuity in creating a community and an informal economy, the cost in social disorder is high. Tension and crowding create health problems. Because birth control is generally unavailable, refugee women have an average of 5.78 children each. Disillusionment is widespread. Years of hopelessness, extreme hardship, and lack of education and rewarding employment take their toll on youth and adults alike. Because of these factors, it is easy for Islamists and jihadists to find new recruits, which they do by providing basic services to camp residents. Moreover, even though international organizations also provide for refugees, the refugees constitute a huge drain on the resources of their host countries. In Jordan, for example, native Jordanians are a minority in their own country because the more than 3 million Palestinian refugees and their children account for well over half the total population of the country, and their presence has changed life for all Jordanians. They have been joined by over 750,000 Iraqis, and as of 2013, more than 250,000 Syrians have crossed into Jordan.

Human Well-Being

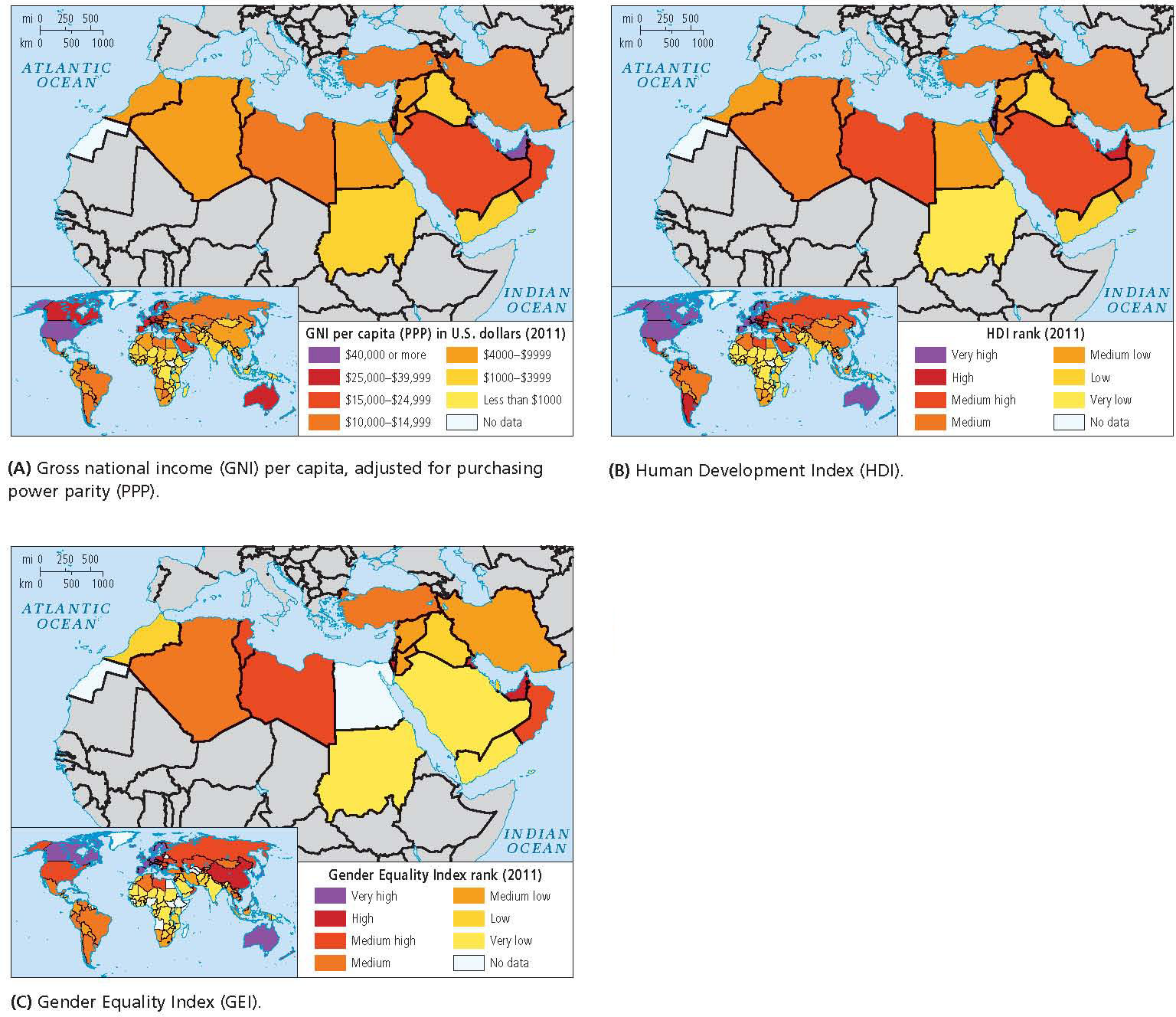

As we have observed in previous chapters, gross national income (GNI) per capita can be used as a general measure of well-being because it shows broadly how much money people in a country have to spend on necessities, but it is only an average figure and does not indicate how income is actually distributed across the population. Thus, it does not show whether income is equally apportioned or whether a few people are rich and most are poor. (As discussed in earlier chapters, the term GNI is often followed by PPP, which indicates that all figures have been adjusted for cost of living and so are comparable.)

Figure 6.24A points to two situations regarding GNI in this region. First, from country to country there is wide variation—less than U.S.$2000 per person per year in Sudan and well over U.S.$47,000 per person per year in Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar. Second, oil and gas wealth does not necessarily translate into high GNI per capita (compare Figure 6.24A with Figure 6.25)—Iraq has significant oil wealth but only very modest GNI per capita. Libya, with more modest oil resources, has a much higher GNI than Iraq. Saudi Arabia, for all its oil wealth, does not have the top GNI per capita. Turkey, which has a diversified economy and very little oil, nonetheless has a GNI rank equal to that of Iran (in the middle range), which has significant oil and gas resources.

Figure 6.24B depicts countries’ rank on the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a calculation (based on adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment) of how adequately a country provides for the well-being of its citizens. In this region, HDI ranks stretch from the medium-low to the high ranges, with Israel ranking the highest (17). If on the HDI scale a country drops below its approximate position on the GNI scale, one might suspect that the lower HDI ranking is due to poor distribution of wealth and poor social services: A critical mass of people are simply not getting a sufficient share of the national income to receive good health care and an education. Kuwait and Oman rank lower on HDI than they do on the GNI scale, indicating that they may not be managing their wealth well enough to ensure the well-being of all—thus, disparities are high. Libya, on the other hand, ranks medium-high on the HDI scale and only in the mid-range on GNI per capita. This probably signifies that at least prior to the revolution of 2011, Libya was investing in the social services that enhance human well-being.

Figure 6.24C shows the regional gender equality (GEI) patterns. Countries are ranked according to the degree to which women and men have equal access to reproductive health, political and educational empowerment, and the labor market. Of the 21 countries, only Israel, Kuwait, the UAE, Oman, Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, and Libya have midlevel rankings. As shown on the world inset map in Figure 6.24C, this region ranks lower on gender equity than do most other parts of the world, including several parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 2Gender and Population This region has the second-highest population growth rate in the world, after that of sub-Saharan Africa. Part of the reason for this is that women are generally poorly educated and tend not to work outside the home. Hence, childbearing remains crucial to a woman’s status, a situation that encourages large families. These conditions are among those called into question by current political movements.

Geographic Insight 2Gender and Population This region has the second-highest population growth rate in the world, after that of sub-Saharan Africa. Part of the reason for this is that women are generally poorly educated and tend not to work outside the home. Hence, childbearing remains crucial to a woman’s status, a situation that encourages large families. These conditions are among those called into question by current political movements. Geographic Insight 3Urbanization and Globalization Two patterns of urbanization, both stimulated by globalization, have emerged in the region. In the oil-rich countries, new luxury-oriented cities are tied to flows of money, goods, and people. Elsewhere, in older cities, economic reforms aimed at improving global competitiveness have brought massive migration by the rural poor into cities, creating crowding and slums.

Geographic Insight 3Urbanization and Globalization Two patterns of urbanization, both stimulated by globalization, have emerged in the region. In the oil-rich countries, new luxury-oriented cities are tied to flows of money, goods, and people. Elsewhere, in older cities, economic reforms aimed at improving global competitiveness have brought massive migration by the rural poor into cities, creating crowding and slums. In terms of human well-being, this region is beginning to make improvements, but its overall rankings remain low. Recent political turmoil has reduced human well-being.

In terms of human well-being, this region is beginning to make improvements, but its overall rankings remain low. Recent political turmoil has reduced human well-being.