Economic and Political Issues

There are major economic and political barriers to peace and prosperity within North Africa and Southwest Asia. Wealth from fossil fuel exports remains in the hands of a few elite families. Most people are low-wage urban workers or relatively poor farmers or herders. The economic base is unstable because the main resources are fossil fuels and agricultural commodities, both of which are subject to wide price fluctuations on world markets. Meanwhile, in many poorer countries, large national debts and the need to stay competitive in the global market are forcing governments to streamline production and cut jobs and social services.

Political and economic cooperation in the region has been thwarted by a complex tangle of hostilities between neighboring countries. Many of these hostilities are the legacy of outside interference by Europe and the United States in regional politics, including colonial intrusions in earlier times and, more recently, the activities by global oil, gas, industrial, and agricultural corporations. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which has profoundly affected politics throughout the region, is rooted in the persecution of the Jews in nineteenth-century Europe, culminating in the World War II Holocaust and its aftermath. The Iran-Iraq war of 1980–1988 and the Gulf War of 1990–1991 were instigated in part by pressures on petroleum resources, again from Europe and America. The long siege of violence in Iraq, though begun by a homegrown dictator, came to a head when the United States invaded and occupied Iraq, beginning in March of 2003 and formally ending on December 15, 2011.

Globalization, Development, and Fossil Fuel Exports

Geographic Insight 4

Development and Globalization: The vast fossil fuel resources of a few countries have transformed economic development in them and driven globalization in this region. In these countries, economies have become powerfully linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. Politics have also become globalized, with Europe and the United States strongly influencing many governments.

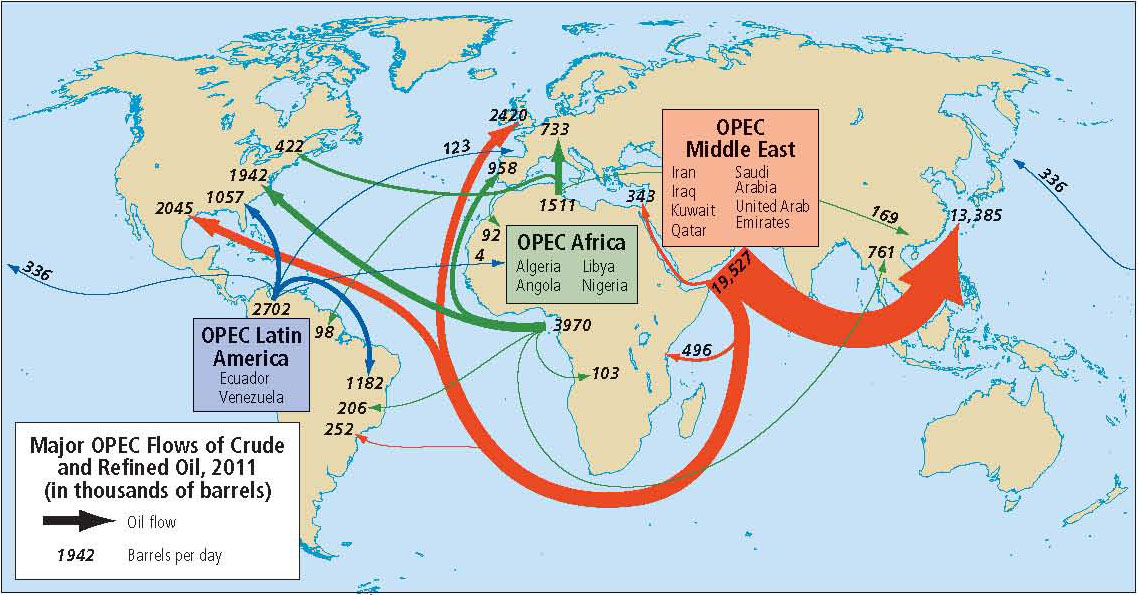

With two-thirds of the world’s known reserves of oil and natural gas, this region is the major fossil fuel supplier to the world. Most oil and gas reserves are located around the Persian Gulf (see Figure 6.25) in the countries of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE. The North African countries of Algeria, Libya, and Sudan also have oil and gas reserves. It is important to note, however, that several countries in this region have minimal oil and gas resources or are net importers of fossil fuels: Morocco, Tunisia, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Turkey. Meanwhile, Egypt and Sudan produce enough to supply most of their own needs, but export little. But regardless of their own petroleum resources, all countries in the region are affected by the geopolitics of oil and gas.

European and North American companies were the first to exploit the region’s fossil fuel reserves early in the twentieth century. These companies paid governments a small royalty for the right to extract oil (natural gas was not widely exploited in this region until the 1960s, though gas extraction has grown rapidly since then). Oil was processed at on-site refineries owned by the foreign companies and sold at very low prices, primarily to Europe and the United States and eventually to other countries, such as Japan.

cartel a group of producers strong enough to control production and set prices for products

OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) a cartel of oil-producing countries—including Algeria, Angola, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Ecuador, and Venezuela—that was established to regulate the production and price of oil and natural gas

Many OPEC countries, which were exceedingly poor just 40 years ago, have become much wealthier since 1973, but they have also become more vulnerable to economic downturns. For example, oil income in Saudi Arabia shot up from U.S.$2.7 billion in 1971 to U.S.$110 billion in 1981, to U.S.$592.4 billion in 2012. But this wealth has not been widely shared within OPEC countries or within the region. The Gulf states were slow to invest their fossil fuel earnings at home in basic human resources, and they were slow to explore other economic strategies in case oil and gas ran out. Like their poorer neighbors, OPEC countries remain highly dependent on the industrialized world for their technology, manufactured goods, skilled labor, and expertise. Recently, the Gulf states have begun to invest heavily in roads, airports, new cities, irrigated agriculture, and petrochemical industries. Saudi Arabia is investing in six new cities in different parts of the country to spur investment and advance economic and social development. A good example of the scale of projects in the Gulf states is Palm Jumeirah (Palm Island) in Dubai, UAE (see Figure 6.23A), which is intended to be the centerpiece of Dubai’s planned tourism economy—insurance against the day when the regional oil economy fails for whatever reason. The recession that started in 2008 badly damaged the economies of the Gulf states. Most of the massive building projects underway across the Gulf states screeched to a halt, including Palm Island and similar projects in the UAE. The recession demonstrated that Dubai’s tourism economy is highly vulnerable to economic downturns, and as mentioned, with drastically fewer jobs available, countries that have many temporary workers, as in the Gulf states, have seen a steep decline in remittances sent home.

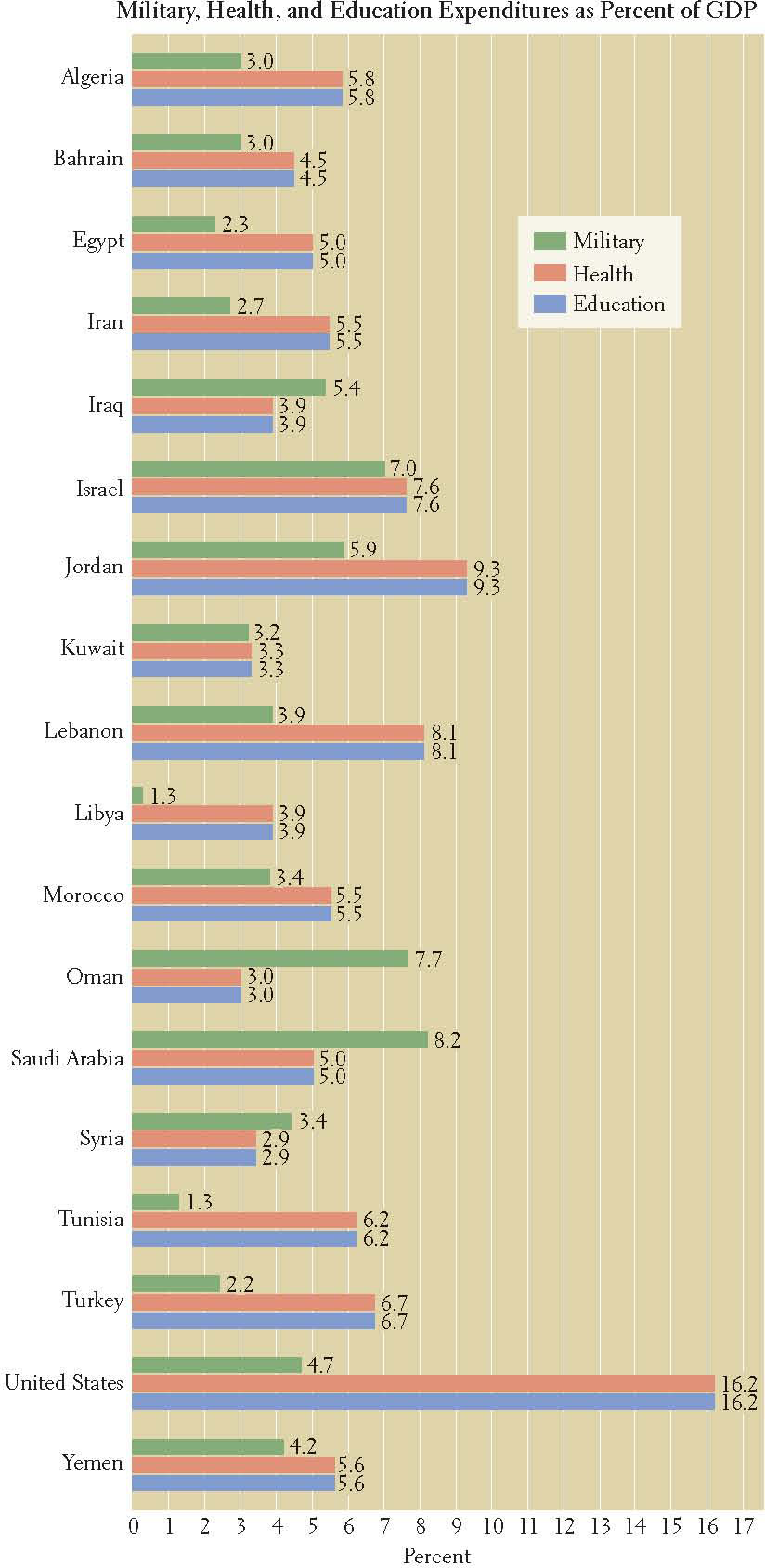

Resources have been poured primarily into visible physical development; much less oil wealth has been invested in education, social services, public housing, and health care. Libya, before the Arab Spring, and Kuwait are exceptions to this pattern, having developed ambitious plans for addressing all social service needs, with especially heavy investment in higher education. Iran is another possible exception, though because the Iranian government shares very little of its data with the rest of the world, it is hard to be certain how much it is investing in social services. Meanwhile, the non-OPEC countries (those that do not produce fossil fuels) do not share directly in the wealth of the Persian

Gulf states, and for the most part, the oil-rich countries have not helped their poorer neighbors develop.

Many factors beyond OPEC’s control strongly influence world oil prices. Recent rapid industrialization in China and India has increased their demand for fuel and other petroleum products, creating long-term pressures that are raising the price of oil. Employing a theory known as “peak oil,” some experts argue that in an era of diminished oil reserves—which these experts say has already begun—prices will be driven higher. On the other hand, efforts to combat climate change with renewable energy sources have been increasingly successful and could dramatically reduce demand for oil. Current global oil flows are summarized in Figure 6.26.

Economic Diversification and Growth

economic diversification the expansion of an economy to include a wider array of activities

By far the most diverse economy in the region is that of Israel, which has a large knowledge-based service economy and a particularly solid manufacturing base. Israel’s goods and services and the products of its modern agricultural sector are exported worldwide. Turkey is the next most diversified, in part because—like Israel—it has never had oil income to fall back on. Egypt, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia are also starting to move into many new economic activities. Some fossil fuel-rich countries tried to diversify into other industries. This was true in Syria until the dictator Bashar al-Assad refused to respond to civil protests from an economically stressed citizenry, which precipitated a revolution (see the next section). A somewhat more responsive government in the UAE developed an economy where only 25 percent of GDP is based directly on fossil fuels, and where trade, tourism, manufacturing, and financial services are now dominant. Even so, most Gulf states are still highly dependent on fossil fuel exports and the spin-off industries they generate.

Diversification has also been limited by economic development policies that favored import substitution (see Chapter 3). Beginning in the 1950s, many governments, such as those of Turkey, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Tunisia, and Libya, established state-owned enterprises to produce goods for local consumption. Among the major products were machinery and metal items, textiles, cement, processed food, paper, and printing. These enterprises were protected from foreign competition by tariffs and other trade barriers. With only small local markets to cater to, profitability was low and the goods were relatively expensive. Without competitors, the products tended to be shoddy and unsuitable for sale in the global marketplace. Meanwhile, the extension of government control into so many parts of the economy nurtured corruption and bribery and squelched entrepreneurialism. Many of the state-owned import substitution enterprises have subsequently either gone bankrupt or been sold to private investors.

Economic diversification and export growth were also limited by a lack of financing, private and public, from within the region. For example, rather than invest locally in mundane but needed consumer products, members of the Saudi royal family generally invest their wealth in more profitable private firms in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. Even when private and public investment has stayed in the region, it has gone into lavish projects, such as those in Dubai that give jobs to skilled Asians and may not necessarily prove to be economically profitable. Only recently have governments recognized that they need to invest locally in order to plan wisely for a time when oil and gas run out.

Finally, both international and domestic military conflicts and the ensuing political tensions have stymied economic diversification because they have resulted in some of the highest levels (proportionate to GDP) of military spending in the world. Military spending diverts funds from other types of development, such as health care and education (Figure 6.27). The top four spenders—Oman, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq—lead the world in military expenditures as a percentage of GDP. And all countries in the region, except Tunisia, are above the global average of 2 percent.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 4Development and Globalization The entire region has been influenced by the huge profits earned by a relatively few countries from petroleum resources. The economies of all countries in the region are linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. For many decades, Europe and the United States have strongly influenced the governments of most of these countries.

Geographic Insight 4Development and Globalization The entire region has been influenced by the huge profits earned by a relatively few countries from petroleum resources. The economies of all countries in the region are linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. For many decades, Europe and the United States have strongly influenced the governments of most of these countries. Profits in the oil- and gas-producing countries were low until OPEC initiated price increases in 1973. Since then, wealth has accrued mainly to a privileged few.

Profits in the oil- and gas-producing countries were low until OPEC initiated price increases in 1973. Since then, wealth has accrued mainly to a privileged few. Until very recently, countries in the region, with the exception of Turkey and Israel, had not diversified their economies. In the Gulf states, huge profits have not been invested at home, but rather abroad, thus limiting diversification. When import substitution policies have been tried, they have failed to lift countries out of poverty.

Until very recently, countries in the region, with the exception of Turkey and Israel, had not diversified their economies. In the Gulf states, huge profits have not been invested at home, but rather abroad, thus limiting diversification. When import substitution policies have been tried, they have failed to lift countries out of poverty.

Power and Politics: The Arab Spring

Geographic Insight 5

Power, Politics, and Gender: Despite the predominance of elected bodies of government, and the increasing participation of women as voters, wealthy, politically connected males, clerics, and often the military retain the real power. Waves of protest, which included some women participants, swept this region, beginning with the Arab Spring of 2010, and resulted in the overthrow of several authoritarian governments. Within the region, official response to the Arab Spring has included both repression and reforms, but only a few of the positive changes hold promise for women.

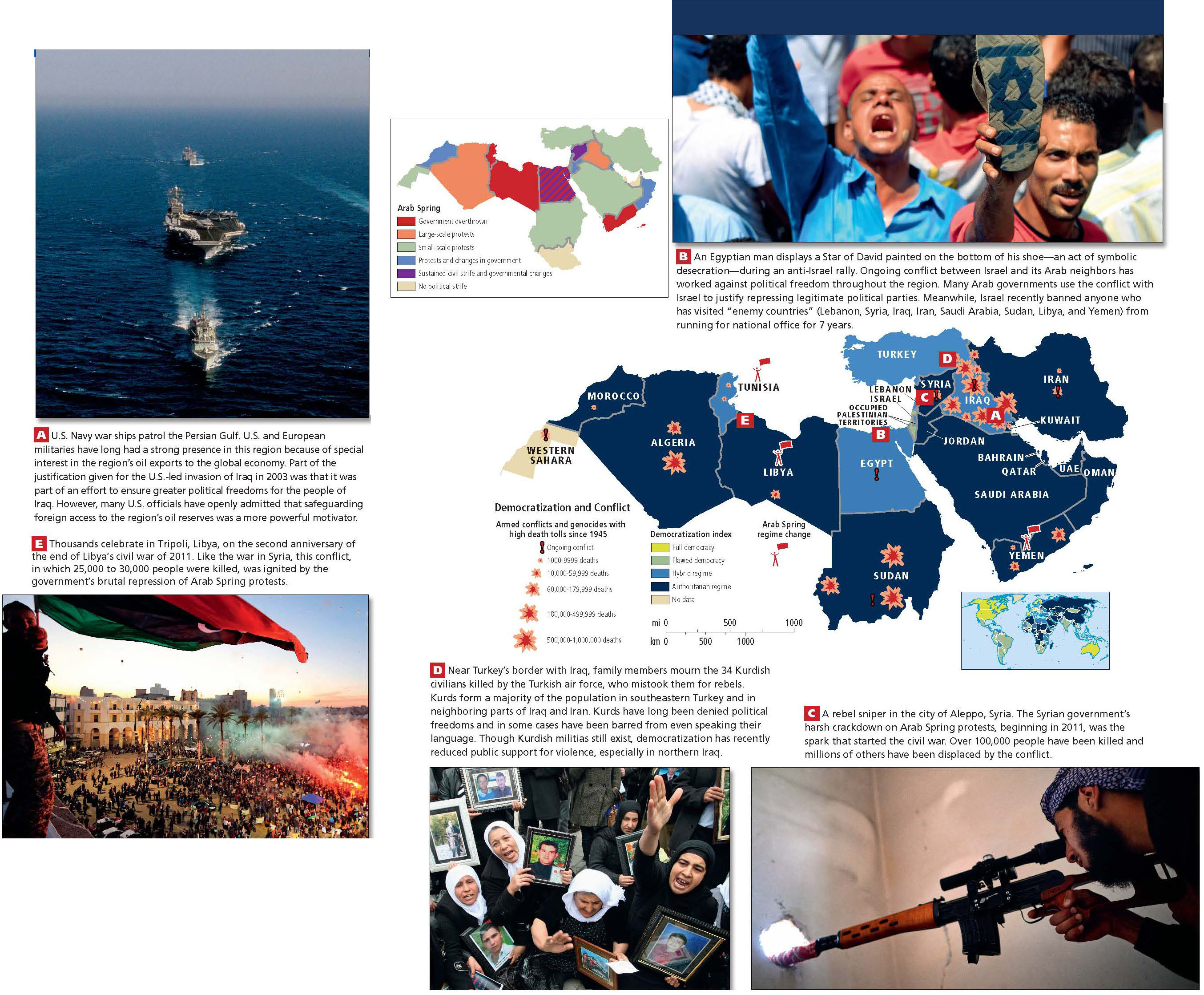

The political protests that swept across North Africa in 2010 and into Syria by 2011 eventually resulted in the toppling of long-standing dictators in Tunisia, Egypt, and then Libya. The protest movement also presented an increasingly serious threat to President Assad in Syria. The early demonstrations were precipitated by high unemployment and rising food prices caused by the global recession that began in 2008; chronic poor living conditions; government corruption; and the absence of freedom of speech and other political freedoms. An undercurrent of dissent among women was also palpable in every country; a side effect was that movements for women’s rights and human rights generally were rejuvenated (see the opening vignette).

The political disquiet reflected the fact that, for much of their history, most governments in this region gave citizens very little ability to influence how decisions were made. Constitutions were not constructed to facilitate widespread participation in public discourse or to protect women’s and minorities’ points of view. Laws were simply interpreted to suit the factions that held power. Elections were either nonexistent or were rigged to reelect those already in office or their chosen successors. Meanwhile, freedom of speech and of the press was strictly limited, especially if it involved criticism of the government. As a result, people across the region saw their governments as unresponsive and corrupt, and themselves as powerless to influence government in any way other than by massive protests.

Certainly, the role that Islam should play in society has been the most contentious issue of long-term significance, and it relates directly to determining which system of laws should be adopted as well as which protections women should be afforded.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Arab Spring as a Conduit for New Ideas

The potential for the Arab Spring to introduce political and social change quickly into this region was at first overstated. Certainly the trajectory of change is different and the pace slower than anticipated by optimists. As of this writing (August 2013), it is clear—as the demonstrations and debates have shown—that things will not return to the former status quo of purely male elitist control. The public shift toward support for democracy has the potential to reduce violence because the possibility of having a voice tends to curb anger. Furthermore, officials in many countries have now seen the power of public protests and are motivated to engage in dialogue.

Which First: Elections or Constitutions?

The Arab Spring movement began in Tunisia and spread to Egypt, then to Libya, and eventually to every country in the region—including Iran—with the exceptions of Israel, Qatar, Turkey, and the UAE. The size and focus of the protests varied, but they all raised hopes for democratic reforms. Unfortunately, there were no viable reform models extant within the region to follow. Should constitutions be revised first to guarantee freedoms and equal participation for all, or should elections come first with the winning majority framing the new constitutions? Tunisia and Egypt chose to have elections first, but turnout was so low that not even one-third of the eligible voters participated. As a result in both cases, Islamist-oriented governments were elected. These governments then proceeded to adopt constitutions that did not adequately provide for the rights of more secular political groups, minorities, or women.

An American commentator on international politics, Fareed Zakaria, observed in 2013 that the thoughtful and cautious approaches to reform chosen by the kings of Jordan and Morocco—before full-blown Arab Spring movements developed—seem to have better served the evolution of democratic institutions in this region. In both cases, the respective kings negotiated with reformists to keep some of their royal powers while agreeing to give up others. They both supported the idea that lasting political reform should begin with constitutional reforms hammered out not by elected bodies, but by constitutional councils made up of a broad range of people. These councils were charged with making the political systems more democratic and inclusive, and in both cases women were significantly represented, as were religious minorities and those with secular points of view. Both kings were soundly criticized during the transition, but they accepted this as part of the process toward eventual constitutional monarchies. When elections were held, candidates from a wide range of positions won. In Morocco, for example, an Islamist party won a plurality of the seats in parliament (107 out of 395 seats) and formed the government; but with only a little over a quarter of the total seats, the Islamists had to accept cooperation and compromise as a necessity, an important precedent for the future.

In Egypt, by contrast, where elections were the first priority, the highly organized Muslim Brotherhood mobilized their supporters and swept to power with only a minority of the electorate voting. Having won, the Muslim Brotherhood then controlled the writing of a constitution that gave the government authoritarian powers, rejected the already weak protections of women’s rights that had been in place by, for example, reaffirming the custom that all women required the guardianship of a male, and undermined the rights of religious minorities. Freedoms of speech, most notably those of journalists, were also sharply curtailed. Then within a few weeks, after President Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood stalwart, declared that he had powers that superseded those of the Egyptian courts, he was deposed in a military coup.

Islamism and the Arab Spring in a Globalizing World

Salafism an extreme, purist Qur’an-based version of Islam that has little room for adaptation to modern times

As mentioned, in both Tunisia and Egypt, Islamists won enough votes in elections to give them control of the national government. In both countries, these newly empowered Islamists, having displayed authoritarian tendencies themselves, now face Arab Spring-style protest movements led by more secularly inclined groups.

139. WHAT MOTIVATES A TERRORIST?

139. WHAT MOTIVATES A TERRORIST?

140. NEW POLL OF ISLAMIC WORLD SAYS MOST MUSLIMS REJECT TERRORISM

140. NEW POLL OF ISLAMIC WORLD SAYS MOST MUSLIMS REJECT TERRORISM

144. JIHADIST IDEOLOGY AND THE WAR ON TERROR

144. JIHADIST IDEOLOGY AND THE WAR ON TERROR

theocratic states countries that require all government leaders to subscribe to a state religion and all citizens to follow rules decreed by that religion

secular states countries that have no official state religion and in which religion has no direct influence on affairs of state or civil law

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about democratization and conflict in North Africa and Southwest Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What circumstances made many suspicious of the U.S. claim that the 2003 war with Iraq was undertaken to bring democracy to that country?

What circumstances made many suspicious of the U.S. claim that the 2003 war with Iraq was undertaken to bring democracy to that country?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why is the 1973 war between Israel and Egypt cited as one of the causes of political repression within countries of the region?

Why is the 1973 war between Israel and Egypt cited as one of the causes of political repression within countries of the region?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What were the issues that motivated Syrians to take to the streets in prolonged demonstrations in 2011?

What were the issues that motivated Syrians to take to the streets in prolonged demonstrations in 2011?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What has changed for Kurds in Iraq that has lessened their use of violent protests?

What has changed for Kurds in Iraq that has lessened their use of violent protests?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The militancy often associated with Islamism is characteristic of many popular political movements in this region, where challenges to the authority of governments are frequently met with violent repression (see the Figure 6.28 map). In both secular and theocratic governments, political freedoms are sometimes so weak that minorities have been denied the right to engage in their own cultural practices and to speak their own languages. Journalists and private citizens have been harassed, jailed, or even killed for criticizing governments or exposing corruption. While the Arab Spring protests that swept through this region were in part a response to these conditions, the extent to which the new governments and political reforms will protect political freedoms remains to be seen.  153. TURKEY VOTES FOR STABILITY

153. TURKEY VOTES FOR STABILITY

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Reforms for Women Could Solve Labor Problems

An important impetus for change in the region is the increasing number of women who are becoming educated and employed outside the home. In a number of countries, women outnumber men in universities; most notably, in Saudi Arabia women make up 70 percent of university students (but only 5 percent of the workforce). While Saudi women activists have characterized their country as practicing a sort of apartheid with its own women, circumscribing or forbidding all manner of public activities, and while laws there still require a male guardian to accompany an adult woman when she leaves the house, change is in the wind. Recently, a Saudi prince, known for his interests in reform, suggested that one way to reduce dependence on foreign workers is to allow Saudi women to become drivers of taxis and trucks, as is now allowed in Jordan. [Source: www.trust.org/trustlaw/news/saudi-prince-questions-ban-on-women-driving]

Will There Be an Iranian Spring?

When the political protests known as the Arab Spring erupted across North Africa, many wondered if Iran (which is not Arab) would join in the protests. A seeming prelude occurred in June 2009, when many Iranians suspected the presidential elections had been rigged. Tens of thousands of people in Tehran took to the streets in protest and on certain days their numbers exceeded 100,000. The main opposition force was the Green Party, which felt its candidate had been cheated by election fraud. A number of prominent Iranian private citizens joined with the Green Party protestors. The demonstrations first focused on election fraud, but when the Iranian police killed several unarmed demonstrators, the center of protest attention became the brutality of the autocratic, theocratic state and the need for democratic reforms as well as improvements in women’s rights. But while the street protests became more and more radical, calling for an end to the Islamic state, no symbolic leader or rallying cause emerged around which all could unite.

The Iranian street protests persisted into 2010, when the activities of the Arab Spring in North Africa began. By February of 2013, protestors in Iran had a variety of topics on their minds; the need for democratic reforms was still central, as was Iran’s international status, which was of concern for two reasons. Iran’s ongoing uranium enrichment program and the threat that it would develop an atomic bomb had resulted in Western sanctions against Iran’s oil trade (Iran’s oil exports declined by as much as half in 2012 and the value of the country’s currency plummeted; see also Figure 6.26 for patterns of oil distribution). Also, Iranian protestors objected to their country’s support for Syrian president Bashar al-Assad as he repressed the increasingly strong rebellions against his regime. In the Iranian presidential elections of June 2013, with 72 percent of eligible voters participating, a moderate, Hassan Rouhani, was elected, winning three times as many votes as his nearest competitor. He called for improved international relations and a stronger economy less dependent on imports. Despite this apparent shift in focus for Iran’s leadership, dissent continues to be expressed in Iran, so the durability of the political awakening remains in question.

The Role of the Press, Media, and Internet in Political Change

In some countries—Turkey, Israel, and Morocco, for example—the press is reasonably free and opposition newspapers are aggressive in their criticism of the government. But in much of the region, journalism can be a risky career, often leading to imprisonment. Egypt has a checkered history where the press is concerned. For years, the Mubarek government harassed Hisham Kassem, editor of the independent English-language weekly Cairo Times. When he became too critical of the government, he lost his license to publish in Egypt. For a time he took great pains to write and print his paper outside the country and smuggle it into Egypt, always risking arrest. Business leaders in Cairo began to provide backing for Kassem, enabling him to publish Al-Masry Al-Youm, which specialized in domestic issues of corruption, election fraud, and the need for an independent judiciary. Kassem and many independent journalists like him participated actively in the 2011 protests in Egypt that brought an end to the 30-year regime of Hosni Mubarak. In this he shared a common cause with Egypt’s formerly repressed Islamist opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood, which won control of the national government in elections in 2012. However, Kassem and many in the media returned to harsh criticism of the Muslim Brotherhood-led government for censoring print and broadcast journalists who were critical of the government.

In Saudi Arabia, a dozen newspapers are on the newsstands every morning, but all are owned or controlled by the royal Saud family, and all journalists are constrained by the fact that they may not print anything critical of Islam or of the Saud family, which numbers in the tens of thousands. When accidents happen or some malfeasance by a public official is revealed, the story is blandly reported, with little effort to explore the causes of events or their effects or to hold responsible officials accountable.

A beacon of journalistic change is the broadcasting network Al Jazeera, founded by the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, but now privately owned and independent of the Qatar government. Al Jazeera is credited with changing the climate for public discourse across the region and even with changing public opinion outside of the region through Al Jazeera English, the source of some of the information used in the opening vignette. The various versions of Al Jazeera now openly cover controversy, including reforms proposed by the most radical Iranian and Arab Spring protesters, with no apparent censorship.

147. AL JAZEERA LAUNCHES GLOBAL BROADCAST OPERATION

147. AL JAZEERA LAUNCHES GLOBAL BROADCAST OPERATION

The role of the Internet and cell phone technology as a force for political change emerged first during the Iranian protests beginning in 2009, when the fact that so many Iranians had video-capable cell phones meant that the world instantly saw via the Internet the brutality of the Iranian police and army. Use of the Internet (e-mail, Facebook, crowdsourcing, and Twitter) became commonplace during the Arab Spring, when ordinary Egyptians and Libyans with nothing but an inexpensive cell phone were able to give real-time reports about activities in the streets of Cairo, Tripoli, and Banghazi. Twitter became the chief medium because it is free, mobile, and quick. The data from many sources could then be compiled via software, such as Ushahidi, invented and made popular by several Kenyan engineers (discussed in the opening vignette of Chapter 7).

Democratization and Women

Most countries in this region now allow women to vote, and two countries—Israel and Turkey—have elected female heads of state (prime ministers) in the past. Nevertheless, women who want to actively participate in politics still face many barriers. In the Gulf states, where women’s political status is the lowest, circumstances vary from country to country. Oman gave all women the right to vote in 2003. In Kuwait in 2009, four highly educated women were elected to parliament; they quickly energized the pace of law making, often publicly criticizing their male colleagues, who were frequently absent for crucial votes. In Saudi Arabia, by contrast, women will be given the right to vote only in local elections in 2015, and only one Saudi woman serves as a public official. Across the region, women average less than 12 percent of national legislatures, the lowest of any world region and half the world average. By 2013, Saudi Arabia had appointed, not elected, women to 20 percent of Parliament seats, and only in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Morocco, and Sudan did women make up more than 15 percent of parliaments. Women lost ground in Egypt when the post-Arab Spring elections in 2012 brought fewer women to office than there were before. Moreover, there is a tendency—even among women—to not support female candidates.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Power and Politics While the immediate causes of the Arab Spring demonstrations may be economic, activists who have long promoted increased political freedoms as a path to peace in this region have been energized by the protests and continue their work to end authoritarian rule. Women participants have thus far been both encouraged and disappointed by the results.

Power and Politics While the immediate causes of the Arab Spring demonstrations may be economic, activists who have long promoted increased political freedoms as a path to peace in this region have been energized by the protests and continue their work to end authoritarian rule. Women participants have thus far been both encouraged and disappointed by the results. Demand for greater political freedoms is increasing, and public spaces for debate, other than mosques, are emerging. The press is reasonably free in some countries and severely curtailed in others. Al Jazeera is credited with changing the climate for public discourse across the region and with modifying public opinion outside the region.

Demand for greater political freedoms is increasing, and public spaces for debate, other than mosques, are emerging. The press is reasonably free in some countries and severely curtailed in others. Al Jazeera is credited with changing the climate for public discourse across the region and with modifying public opinion outside the region. Most countries now allow women to vote, and the two most developed countries have elected female heads of state. Even though women who want to actively participate in politics still face barriers, patterns are changing as more women become educated and employed outside the home.

Most countries now allow women to vote, and the two most developed countries have elected female heads of state. Even though women who want to actively participate in politics still face barriers, patterns are changing as more women become educated and employed outside the home.