Three Worrisome Geopolitical Situations in the Region

The region of North Africa and Southwest Asia is known as a center of especially troublesome political issues that command the attention of major global powers. These issues can all be related in one way or another to the politics of the international oil trade (see Figure 6.28A), and at least one may be related to global climate change.

Situation 1: Fifty Years of Trouble Between Iraq and the United States, 1963 to 2013

The origins of the U.S. war with Iraq, beginning in 2003, lie in 1963, when the United States backed a coup that installed a pro-U.S. government that evolved into the regime of Saddam Hussein. For decades, the United States had an amicable relationship with the Iraqi government, driven in large part by Iraq’s considerable oil reserves, the fourth largest in the world after those of Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Iran. The United States publicly supported Iraq in the 1980–1988 war between Iraq and Iran, but secretly supplied Iran with weapons during the Reagan administration (1981–1989) when it appeared that Iraq might become more troublesome if it won the war. Relations with Iraq took a dramatic turn for the worse in 1990 when Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s dictator, invaded Kuwait. The United States, under President George H. Bush, forced Iraq’s military out of Kuwait in the Gulf War of 1990–1991, and afterward placed Iraq under crippling economic sanctions, but they failed to tame Saddam Hussein (see Figure 6.7D).

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. administration of George W. Bush (2001–2009) first launched a war on Afghanistan, but by 2003, shifted its focus to Iraq and its autocratic president, Saddam Hussein (see Chapter 2). The Bush administration claimed that Iraq had or was creating an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction and used this pretext to declare war on March 20, 2003, with the goals of confiscating Iraq’s weapons, removing Hussein from power, and turning Iraq into a democracy.

After the initial invasion met little resistance, President Bush declared the war won on May 1, 2003. However, terrorist bombs and insurgent attacks soon erupted, with violence peaking between 2006 and 2007, after which it gradually decreased but did not cease. By March 2013, a total of 4422 U.S. troops had been killed and 31,926 had been wounded. Furthermore, over 150,000 veterans of the conflict had been diagnosed with some form of serious mental disorder, including posttraumatic stress (PTSD). The death toll for Iraqis, including civilians, was much higher, estimated as at least 111,407 and possibly as high as 1.3 million when counting Iraqi deaths caused by the harsh conditions created by the war.

152. FIVE YEARS AFTER ‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’ IN IRAQ, WAR CONTINUES

152. FIVE YEARS AFTER ‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’ IN IRAQ, WAR CONTINUES

The Bush administration’s main stated justification for the war was democratization, but the failure to understand the long-simmering tensions between Iraq’s major religious and ethnic groups crippled the democratization process. Sunnis in the central northwest had dominated the country under Saddam, although they constituted only 32 percent of the population. Shi’ites in the south, with 60 percent of the population, have dominated politics since the fall of Saddam. This has given greater influence to neighboring Iran, whose mostly Shi’ite population feels affinity for Iraqi Shi’as. Meanwhile, Kurds in the northeast, once brutally suppressed under Saddam Hussein, are allied with Kurdish populations in Turkey, Iran, and Syria, and resist cooperating with the Iraqi national government in Baghdad.  134. KURDISH NATIONALISTS IN IRAQ, TURKEY SEEK LAND OF THEIR OWN

134. KURDISH NATIONALISTS IN IRAQ, TURKEY SEEK LAND OF THEIR OWN

Recent studies of Iraqi public opinion indicate that a majority of Iraqis want a strong central government that can protect them from violent insurgents and that can maintain control of the country’s large fossil fuel reserves. Polls also show that the vast majority of Iraqis want all fighting to stop and all U.S. and allied military forces to leave. All U.S. “combat” forces left Iraq in 2012, though thousands of personnel will remain for years to come as trainers and technical support for the Iraqi military.

Situation 2: The State of Israel and the “Question of Palestine”

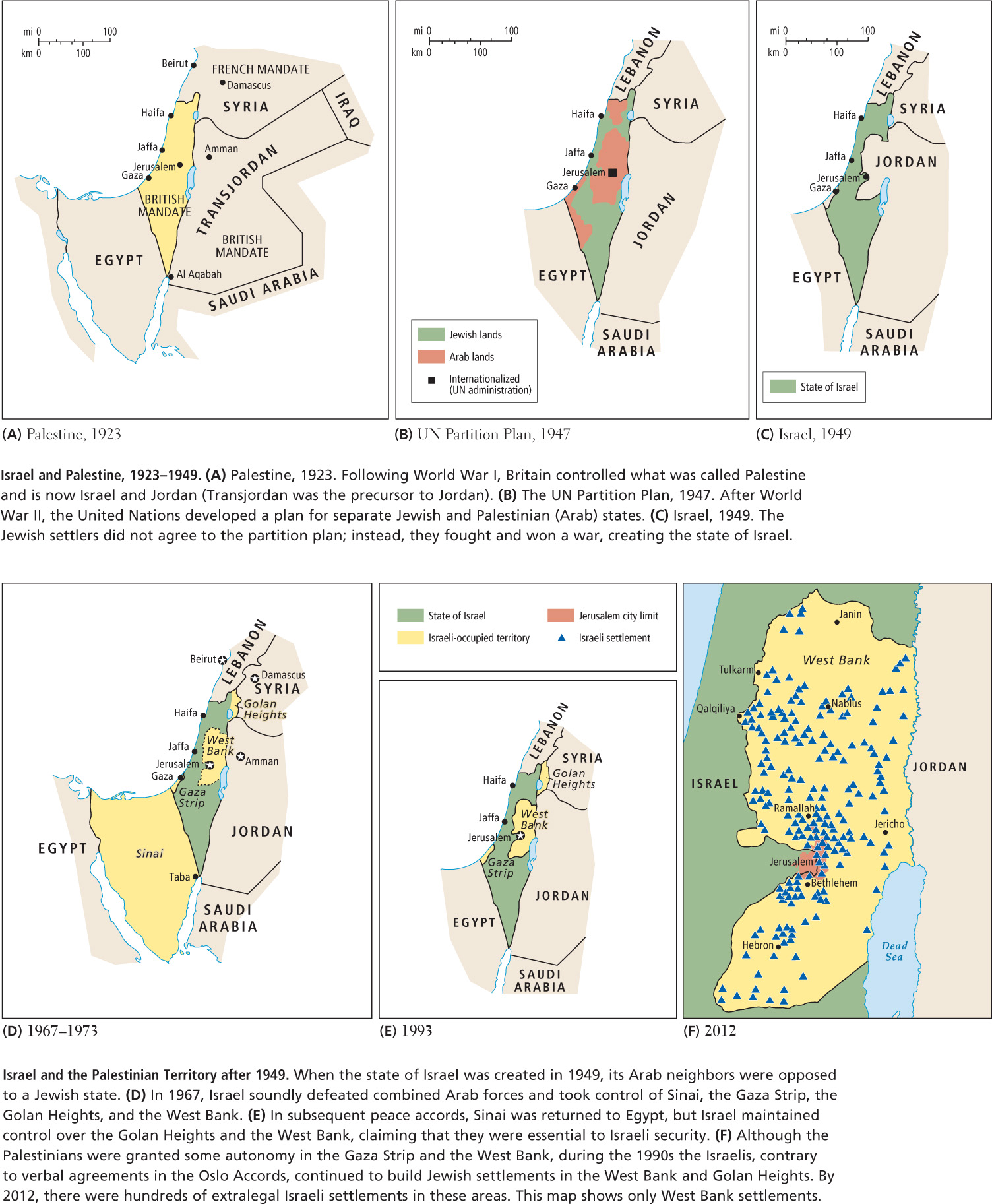

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has lasted more than 60 years and has included several major wars and innumerable skirmishes. It is a persistent obstacle to political and economic cooperation within the region, and it complicates the relations between many countries in this region and the rest of the world (see Figure 6.28B).

Israel’s excellent technical and educational infrastructure, its diverse and prospering economy, and the large aid contributions (public and private) it receives from the United States and elsewhere have made it one of the region’s wealthiest, most technologically advanced and militarily powerful countries.

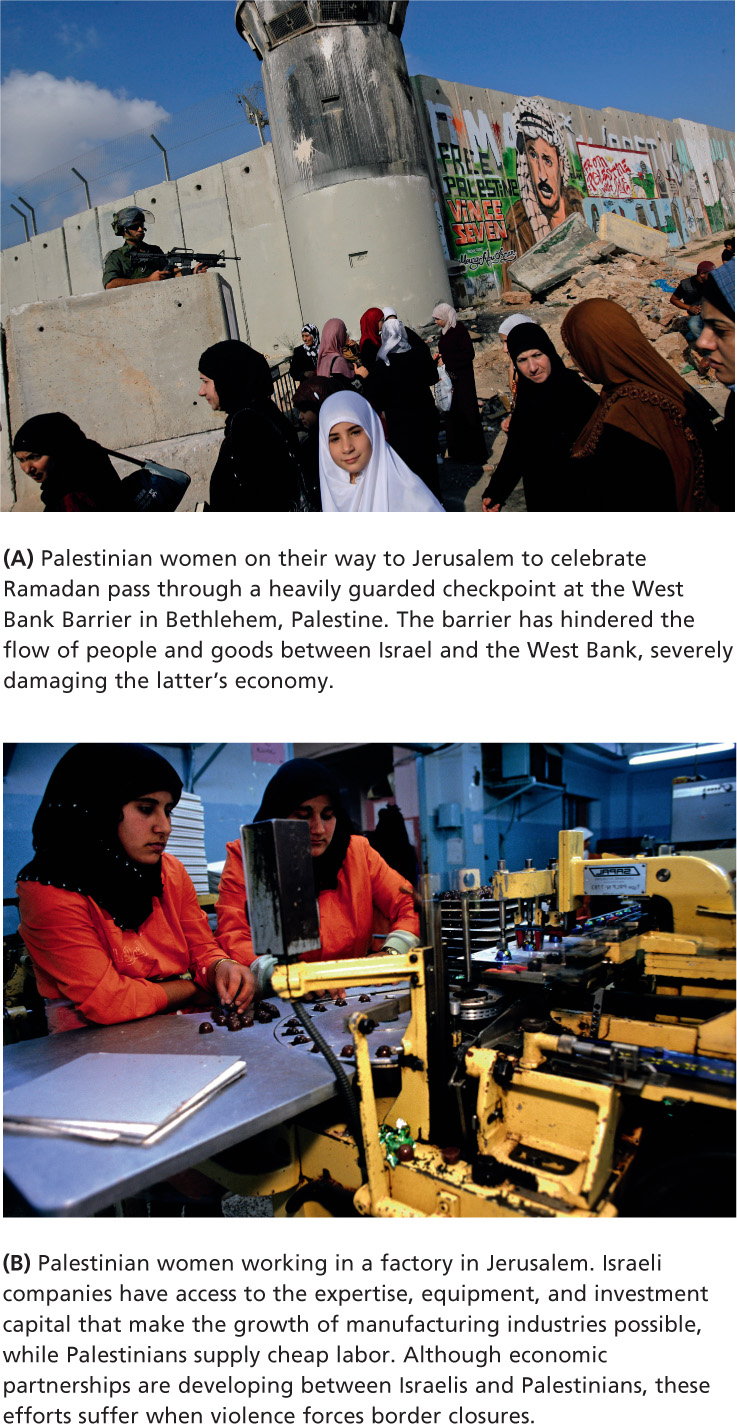

The Palestinian people, by contrast, are severely impoverished and undereducated after years of conflict, inadequate government, and meager living (see Table 6.1), often in refugee camps. Through a series of events over the past 60 years, Palestinians have lost most of the lands on which they used to live. They now live in two main areas—the West Bank (home to 2 million Palestinians) and the Gaza Strip (1.1 million), with another 2 million living as refugees in Jordan, where they outnumber ethnic Jordanians. The West Bank and Gaza are both highly dependent on Israel’s economy. Israel often takes military action in these two zones in retaliation for Palestinian suicide bombings and rocket fire launched primarily from Gaza. The West Bank Palestinian territories continue to be encircled by security walls built by Israel, partly to defend against violence but also to curtail Palestinian access.

| Statistics show some stark differences in well-being between Palestinians and Israelis, including differences in overall satisfaction with life. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (in millions) (mid-2012) | GNI PPP in U.S.$ per capita (2012) | Life expectancy at birth (2012) | Infant mortality rate (2012) | HDI ranks (2012)* | Overall life satisfaction (2011)** | |

| Palestinians | 4.3 | 3359 | 73 | 21 | 110 | 4.7 |

| Israelis | 7.9 | 27,660 | 82 | 3.4 | 16 | 7.4 |

| * See http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/PSE.html | ||||||

| ** Ranked on a scale of 1 to 10, with 0 representing least satisfied and 10 representing most satisfied | ||||||

| Source: Population Reference Bureau 2012 Data Sheet | ||||||

| Human rights report: http://www.hrw.org/middle-eastn-africa/israel-palestine | ||||||

154. 60 YEARS AFTER ISRAEL’S FOUNDING, PALESTINIANS ARE STILL REFUGEES

154. 60 YEARS AFTER ISRAEL’S FOUNDING, PALESTINIANS ARE STILL REFUGEES

The Creation of the State of Israel

Zionists those who have worked, and continue to work, to create a Jewish homeland (Zion) in Palestine

On their newly purchased lands, the Zionists established communal settlements called kibbutzim, into which a small flow of Jews came from Europe and Russia. While Jewish and Palestinian populations intermingled in the early years, tensions emerged as Zionist land purchases displaced more and more Palestinians, seemingly in breach of the Balfour Declaration.

By 1946, following the death of 6 million Jews in Nazi Germany’s death camps during World War II, strong sentiment had grown throughout the world in favor of a Jewish homeland in the space in the eastern Mediterranean that Jews had shared in ancient times with Palestinians and other Arab groups. Hundreds of thousands of Jews began migrating to Palestine, and against British policy, many took up arms to support their goal of a Jewish state.

Sixty Years of Conflict and the Two-State Solution

InNovember 1947, after an intense debate in the UN General Assembly, the UN adopted the “Plan of Partition with an Economic Union” that ended the earlier mandate and called for the creation of both Arab and Jewish states (the two-state solution still under discussion today), with special international status for the city of Jerusalem (see Figure 6.29B).

The Palestinians and neighboring Arab countries fiercely objected to the establishment of a Jewish state and feared that they would continue to lose land and other resources. Then as now, the conflict between Jews and Palestinian Arabs was less about religion than control of land, settlements, and access to water. The sequence of changing allotments of land over time to Israel and to the Palestinians can be followed in Figure 6.29A-F.

On the same day that the British reluctantly ended the mandate and withdrew their forces, May 14, 1948, the Jewish Agency for Palestine unilaterally declared the creation of the state of Israel on the land designated to them by the Plan of Partition. Warfare between the Jews and Palestinians began immediately. Neighboring Arab countries—Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan—supporting the Palestinian Arabs, invaded Israel the next day. Fighting continued for several months, during which Israel prevailed militarily. An armistice was reached in 1949, and as a result,the Palestinians’ land shrank still further, with the remnants incorporated into Jordan and Egypt (see Figure 6.29C).

In the repeated conflicts over the next decades—such as the Six-Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973—Israel again defeated its larger Arab neighbors, expanding into territories formerly controlled by Egypt (Sinai), Syria (Golan Heights), and Jordan (West Bank of the Jordan River; see also Figure 6.29D). Since 1948, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have fled the war zones, with many forcibly removed to refugee camps in nearby countries. Some Palestinians stayed inside Israel and became Israeli citizens, but they have not been treated by the state as equal to Jewish Israelis.

128. HEZBOLLAH—SERVING MUSLIMS WITH GOD AND GUNS

128. HEZBOLLAH—SERVING MUSLIMS WITH GOD AND GUNS

133. LEBANESE OIL SPILL—COLLATERAL DAMAGE OF THE BOMBINGS

133. LEBANESE OIL SPILL—COLLATERAL DAMAGE OF THE BOMBINGS

intifada a prolonged Palestinian uprising against Israel

Over the years since 1947, the vision of a two-state solution has not died. In 2012 the Palestinians, led by their president, Mahmoud Abbas, officially petitioned the UN General Assembly for status as a nonmember observer state. The UN General Assembly voted 138 to 9 to approve this petition (41 nations abstained), and thus the Palestinians gained official recognition that they had never before achieved.

Territorial Disputes

When Israel occupied Palestinian lands in 1967, the UN Security Council passed a resolution requiring Israel to return those lands, known as the occupied Palestinian Territories (oPT), in exchange for peaceful relations between Israel and neighboring Arab states. This land-for-peace formula, which set the stage for an independent Palestinian state, has been only partially fulfilled.

Despite the land-for-peace agreement, between 1967 and 2013, Israel secured ever more control over the land and water resources of the occupied territories. Israel took what appeared to be a major step toward peace in 2005 when it removed all Jewish settlements from the Gaza Strip, but this progress was negated by the blockade of Gaza’s economy and the significantly stepped-up settlement in the West Bank. Between 2005 and mid-2013, some 95,000 new Israeli settlers were added and thousands of Palestinians were displaced.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Economic Interdependence as a Peace Dividend

Though rarely covered in the media, economic cooperation is a fact of life for Israelis and Palestinians and is a crucial component for any two-state solution. Economic ties between Palestine and Israel have long been essential to both. Israel is the largest trading partner of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and provides Palestinians with a currency (the Israeli shekel), electricity, and most imports. Israel needs the labor of tens of thousands of Palestinian workers in fields, factories, and homes (see Figure 6.30B).

Currently, there are several cooperative industrial parks that have been established jointly by the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli government in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Dubbed “peace parks,” the goal of these parks is to use economic development to overcome conflict. Some people are critical of them because Israel tightly controls Palestinian access to the world market. For the peace parks to earn the trust of Palestinians may take some time, given Israel’s history of discouraging industrial development in the occupied territories. Nevertheless, neighboring Israeli and Palestinian cities, such as Gilboa in Israel and Jenin in the West Bank, are pursuing the peace park idea. In 2012, Israelis and Palestinians quietly reached new agreements to increase Palestinian access to jobs in, and trade with, Israel. The agreements address tax procedures, increase the number of entrance permits, and help ease the movement of people through roadblocks.

West Bank barrier a 25-foot-high concrete wall in some places and a fence in others that now surrounds much of the West Bank and encompasses many of the Jewish settlements there

132. WEST BANK BARRIER, NEW DIVIDE IN PALESTINIAN-ISRAELI CONFLICT

132. WEST BANK BARRIER, NEW DIVIDE IN PALESTINIAN-ISRAELI CONFLICT

Situation 3: Failure of the Arab Spring in Syria

The worries raised by the rebellion in Syria (beginning in 2011 and continuing through the present) are basically the same as those raised by all the Arab Spring movements. Can autocratic governments continue to block democratic reforms? Will Islamist factions succeed in taking control from more secular and/or moderate rebels? Will women be able to change patriarchal customs? Will gains in economic development be overwhelmed by the material destruction caused by civil war? In Syria, yet another concern has been raised that carries implications for the entire region: Climate change and the water scarcity that accompanies it (discussed later in this section) are now thought to be among the stressors that helped to bring on the Syrian rebellion.

The political causes of rebellion in Syria are many. Syria used to be one of the more developed countries in the region. Living together peacefully were several factions of Muslims, as well as Christians and even a few Jews; markets were full of life; women could have careers and go out alone past midnight; old men played board games while children played along community streets; tourists flocked to ancient historic sites; and Syrian TV dramas disseminated the Syrian hospitable way of life across the region. But after the authoritarian Assad family swept to power in a bloodless coup in 1970, Syrians had less and less to be proud of. Even before Bashar al-Assad took over what amounted to a police state from his father Hafez in 2000, Syria had gained a reputation for backing assassinations in Lebanon and bombings in Iraq, for building nuclear weapons factories, and for supporting Hezbollah—a Lebanese-based radical Shi’ite group that has close links to Iran and that opposes Israel and uses terrorist tactics.

Although for a time Syrians enjoyed the way the Assads thumbed their noses at the West (the United States and Europe), more educated and secular Syrians could see that their access to decent lives and participation in civic life was being ever more curtailed by the Assad regime. The trappings of a free society, such as shopping malls, Coca-Cola, Internet cafés, and Facebook, no longer pacified when debate, elections, and creativity were quelled by both a police state and a society rife with corruption even in the civil courts.

The Assad family belongs to the minority Alawite sect of Shi’ites, while the majority of Syrians are Sunni Muslims. To keep political equilibrium, the Assads favored a secular state, something like Turkey’s; but Sunnis were kept out of governing circles. Sunni antagonism against Alawites grew because Alawites led particularly privileged lives, with many advantages coming to them from the Assad family.

Several pro-democracy protestors in Damascus who demanded the release of political prisoners were shot dead during March 2011. The protestors persisted, and from the spring of 2011 well into 2013, the Syrian government, backed by the army and aided by weapons and food assistance from Russia and Iran, escalated its attacks on the dissidents. In time, it became apparent that the rebel factions came from opposing points of view—some favoring pro-democratic secular changes, others wanting more Islamist or Salafist conservative reforms. The dissenters were unable to coalesce around common goals for Syria. Although for the most part the Syrian army remained loyal to Assad, some soldiers from Sunni parts of the country defected to the rebels; yet, despite all the destruction and loss of life, at no time did the Assad administration agree to peace-making concessions.

By early 2013, more than 100,000 people had died from violence and related causes, with children making up at least one-third of the dead. Aid agencies estimated that by March of 2013, a million Syrians lacked adequate food, 2.5 million were internally displaced, and 1 million had fled across borders to Turkey, Iraq, Lebanon, and Jordan. Western governments have been reluctant to intervene.

While the political causes of the Syrian civil rebellion are numerous, there is mounting evidence that drought and inappropriate human responses to it have played a role in fueling already well-stoked civil discontent. The Assad government denies that there is a drought, but 70 percent of the ancient qanats (water conduits) have already dried up. Drought is not even acknowledged in the government-controlled press, probably because the government does not want to admit that because of bad management, irrigation projects have failed, crops and herds are dying, and hundreds of thousands of agricultural families have had to move to cities, which are ill-equipped to house and feed them. Syria, the original home of wheat cultivation, must now buy wheat and other grains on a world market in which prices have doubled due to climate change crises in the global centers of wheat production: China, Russia, Ukraine, Australia, and the Americas.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The United States has had a long and meddlesome relationship with Iraq that dates back to the 1960s, when the United States tried to influence Iraq’s internal affairs.

The United States has had a long and meddlesome relationship with Iraq that dates back to the 1960s, when the United States tried to influence Iraq’s internal affairs. While the modern conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is decades old, the situation remains dynamic and complex and continues to be a persistent obstacle to widespread political and economic cooperation in the region.

While the modern conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is decades old, the situation remains dynamic and complex and continues to be a persistent obstacle to widespread political and economic cooperation in the region. Economic cooperation is already a fact of life for Israelis and Palestinians, and more such interaction is a crucial component of any solution to the current conflict. The entire region would benefit from the peace dividend of greater economic cooperation.

Economic cooperation is already a fact of life for Israelis and Palestinians, and more such interaction is a crucial component of any solution to the current conflict. The entire region would benefit from the peace dividend of greater economic cooperation. Political protests against the autocratic Assad regime in Syria have become complicated by the involvement of competing points of view among Islamist, Salafist, secularist, and pro-democracy dissident factions.

Political protests against the autocratic Assad regime in Syria have become complicated by the involvement of competing points of view among Islamist, Salafist, secularist, and pro-democracy dissident factions. A further and as yet little-assessed factor is climate change and the drought Syria has suffered for more than a decade.

A further and as yet little-assessed factor is climate change and the drought Syria has suffered for more than a decade.