Central Africa

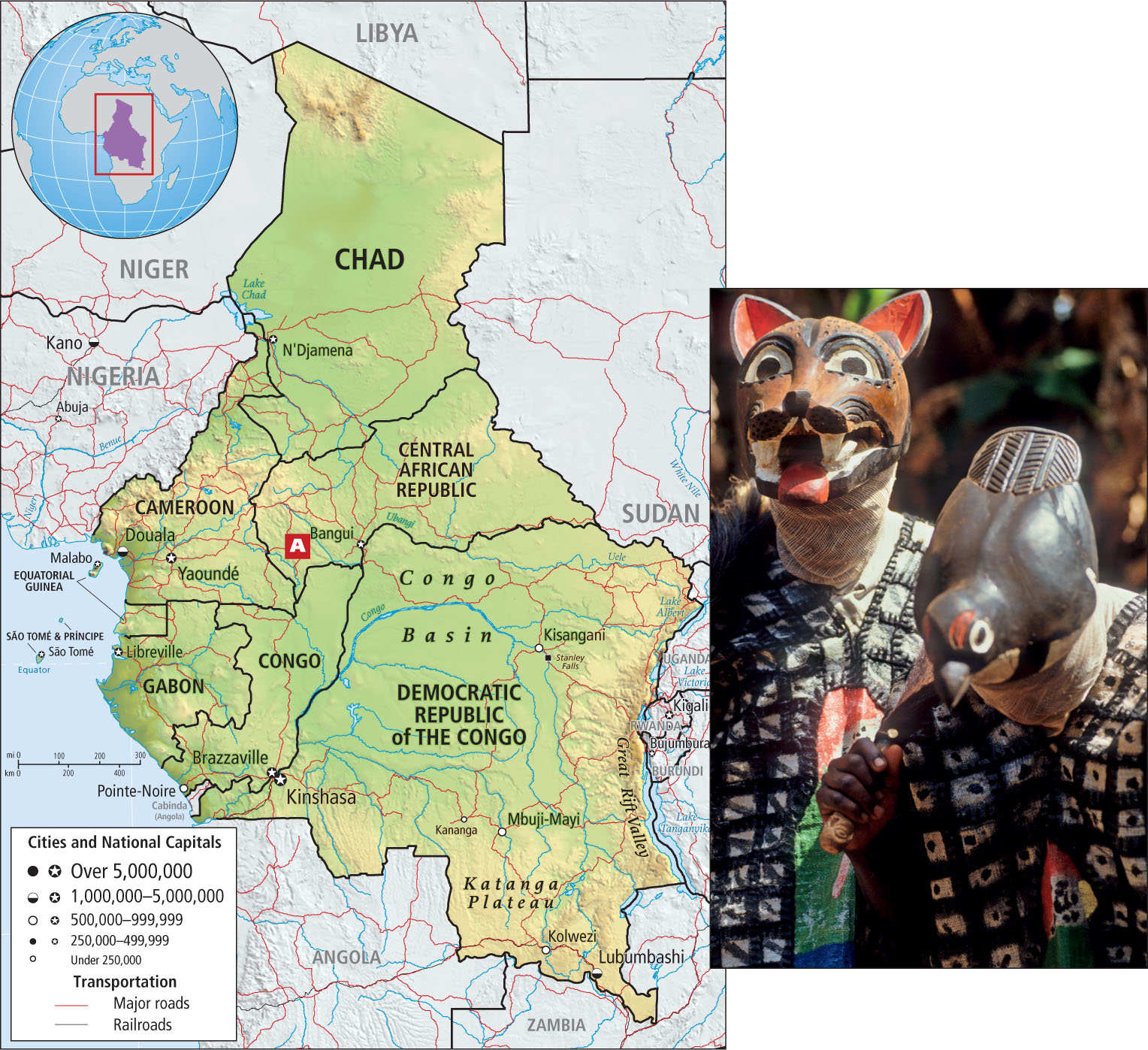

Looking at a map of Africa with no prior knowledge, you might reasonably expect the countries of Central Africa—Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville), Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Congo (Kinshasa)—to be the hub of continental activity, the true center around which life on the continent revolves (shown in the Figure 7.34 map; see also Figure 7.1). Paradoxically, Central Africa plays only a peripheral role on the continent. Its dense tropical forests and its tropical diseases and difficult terrain make it the least accessible part of the continent, and recent armed conflict over resources and power has left it in a deteriorating state that discourages visitors and potential investors.

Wet Forests and Dry Savannas

Central Africa consists of a core of wet tropical forestlands surrounded on the north, south, and east by bands of drier forest and then savanna (see the Figure 7.5 map). The core is the drainage basin of the Congo River, which flows through this area and is fed by a number of tributaries. Although rich in resources, the forests form a barrier that has isolated Central Africa from the rest of the continent for centuries and has impeded the development of transportation, commercial agriculture, and even mining. Moreover, as is true in all tropical zones, the soils of these forests are not suitable for long-term cash-crop agriculture. Most Central Africans are rural subsistence farmers who live along the rivers and the occasional railroad line. The forests themselves are home to nomadic hunter-gatherers, such as the Mbuti and Pygmy people, but these people and their way of life are highly endangered as the scramble for forest and mining resources increases (see Figure 7.34A). Although the sixteenth-century city of Loango on the Congo coast was a model of urban development for its time, during the colonial period and until recently, cities in Central Africa have been small in size, with little urban infrastructure. Now, despite crude urban conditions, cities are growing rapidly, and too often, the newcomers are refugees escaping civil violence in the countryside. The new arrivals find a severe lack of housing, scarce water, poor education systems, and little urban employment in the formal sector.

A Colonial Heritage of Violence

The region’s colonial heritage has contributed to the difficulties described above. In what is now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa), for example, the Belgian colonists left a terrible legacy of brutality. In 1885, Belgium’s king, Leopold II, with a personal fortune to invest, obtained international approval for his own personal colony, the Congo Free State, with the promise that he would end slavery, protect the native people, and guarantee free trade. He did none of these. The Congo Free State consisted of 1 million square miles (2.5 million square kilometers) of tropical forestland rich in wildlife: elephants (who produced ivory), rubber, timber, and copper. King Leopold soon appropriated the labor of the population of 10 million people to extract Congo’s resources for his own profit.

The young writer Joseph Conrad witnessed the cruel behavior of Belgian colonial officials when he obtained a job on a steamer headed up the Congo River in 1890. He saw a campaign of terror that featured enslavement, whipping, beheadings, and lopping off the hands of those who didn’t meet their production quotas for rubber and other commodities. Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (published in 1902), and a pamphlet by Mark Twain, “King Leopold’s Soliloquy” (published in 1905), awakened Europeans and Americans to Leopold’s atrocities, and efforts began to end his regime. However, French colonists in what is now Congo (Brazzaville), Gabon, and the Central African Republic; German colonists in Cameroon; and Portuguese colonists in neighboring Angola used tactics similar to Leopold’s. For example, a chronicler of the 1890s recorded that after a group of Africans rebelled against the French, their heads were used as a decoration around a flowerbed in front of a French official’s home.

Post-Colonial Exploitation

When the countries of Central Africa were granted their independence in the 1960s, the Europeans stayed on to continue their economic domination. Resources were stripped and the tax-free profits sent home to France, Belgium, or Portugal, rather than being reinvested in Central Africa. When the European colonizers departed, leaving Africans with little money to develop an infrastructure (including such things as safe water distribution systems), no experience with multiparty democracy, and no educated constituency, many Central African countries, such as Congo (Kinshasa), fell into the hands of corrupt leaders. The political upheavals that resulted when some groups were left out of representation in government were accompanied by down-ward-spiraling economies. As in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the average person’s purchasing power has decreased over the last few decades. Tax concessions to foreigners, as well as government corruption, have reduced tax revenues; without the revenues, the maintenance of infrastructure, such as roads and electricity grids, has been negligible. Few industries, either government or private, can survive without such facilities. People displaced by civil disruption are so poor that there is little market for any type of consumer product, so even the informal economy is negligible.

A Case Study: Devolution in Congo (Kinshasa) and Signs of Hope

As Belgian colonial officials withdrew in 1960, they left untrained Congolese in charge of the newly independent government. The new head of government, Patrice Lumumba, tried to correct the inequalities of the colonial era by nationalizing foreign-owned companies in order to keep their profits in the country. Lumumba’s strategies, adopted during the height of the Cold War, and the support he received from the Soviet Union, raised the red flag of communism for the West. The Western allies arranged for Lumumba to be killed; they supported and armed politicians who opposed him, such as the corrupt Mobutu Sese Seko.

Mobutu Sese Seko seized power in 1965 and then he, too, nationalized the country’s institutions, businesses, and industries. He did not use the profits for the good of the Congolese people, but rather extracted personal wealth for himself and his supporters from the newly reorganized ventures. Trained technicians and capital left the country, and Congo’s economy, physical infrastructure, educational system, food supply, and social structure declined rapidly. By the 1990s, the vast majority of the Congolese people were impoverished. Laurent Kabila, a new dictator, overthrew Mobutu in 1997. Neighbors to the east (Uganda and Rwanda) who coveted Congo’s mineral wealth supported Kabila, whose inept regime quickly led to widening strife in Central Africa. By 1999, Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Chad, Rwanda, and Uganda all had troops in Congo and were aggressively competing for parts of its territory and resources. More than 4 million Congolese died as a result of the conflict, and 1.6 million were displaced.

Despite the presence of over 20,000 UN peacekeeping forces, the largest such UN mission in the world, the violence ebbed and flowed into the first decade of the twenty-first century. Laurent Kabila was assassinated in 2001. The government was turned over to his son, but chaos continued. In 2006, the UN Security Council officially recognized that the ongoing conflicts in the Great Rift Valley region of Africa (which includes the zone where Congo, Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi come together) were all linked to the illegal exploitation and international trade of natural resources, and to the proliferation of arms trafficking. The Security Council urged all countries to disarm and demobilize their militias and armed groups, especially northern Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army, and to promote the lawful and sustainable use of natural resources. In July 2006, Kabila’s son Joseph won the presidency of Congo in its first multiparty election.

Since 2006, despite the UN efforts, conditions have only deteriorated. The causes of the continuing civil violence (rape, kidnapping, massacres) remain linked to competition for land, power, and resource wealth, especially along the Great Rift Valley border. But global economy investors, including the Chinese government and the American mining firm Freeport-McMoRan, are vying to exploit at great profit Congo’s considerable mineral resources. The Kabila government, reelected in December 2011, had its eye on this potential wealth; but by November 2012, the rebel army M23, based in eastern Congo along the Great Rift Valley, was mounting a major offensive against the Kabila government. Ironically, the ruthless rebels are administered by efficient engineers who say their aim is to reform Congo into a clean, green efficient political system. Rwanda is rumored to be supplying M23.

Despite repetitive violence on the part of foreign and domestic interests, an alternative future is possible. Central Africa has enormous wealth in mineral resources, as well as rare and valuable tropical forest plants and animals (such as bonobos and gorillas). Congo (Kinshasa) is sub-Saharan Africa’s fourth-largest oil producer, and oil is its major foreign trade commodity. Furthermore, while recognizing the environmental damage done by dam building, it should also be noted that Congo (Kinshasa) has enough undeveloped hydroelectric potential to supply power to every household in the country and to those of some neighboring countries as well. Perhaps of greater importance are the natural wonders of the tropical rain forests in which live rare species. White rhinos, Congo peacocks, elephants, okapi, and various types of gorillas are all potential attractions for nature and science tourism (Figure 7.35).

In addition, it is possible that technology paired with creativity may break the cycle of devolution in Congo (Kinshasa), as it is beginning to do elsewhere. Landline phones are virtually nonexistent, but an estimated 25 percent of Congolese have cell phones and use them daily for such activities as sending money to merchants, talking with relatives in remote regions, accessing medical advice, and conducting routine banking (see Figure 7.18). Cell phones could become a major engine of development here, as they have in other sub-Saharan countries. [Source: Washington Post National Weekly Edition and Africa the Good News. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Dense tropical forests, tropical diseases, and difficult terrain make Central Africa the least accessible part of the continent. The Central African subregion has an enormous wealth of natural resources: copper, gold, diamonds, oil, and rare tropical plants and animals. Illegal trade in natural resources, ineffective and corrupt leadership, and the proliferation of arms trafficking are seriously impeding progress.

Dense tropical forests, tropical diseases, and difficult terrain make Central Africa the least accessible part of the continent. The Central African subregion has an enormous wealth of natural resources: copper, gold, diamonds, oil, and rare tropical plants and animals. Illegal trade in natural resources, ineffective and corrupt leadership, and the proliferation of arms trafficking are seriously impeding progress. The shift to democratic institutions in Congo (Kinshasa) is not going well. Elections are now more frequent, but corruption is rampant and democratic institutions weak.

The shift to democratic institutions in Congo (Kinshasa) is not going well. Elections are now more frequent, but corruption is rampant and democratic institutions weak. The roots of conflict in Central Africa are in the colonial era, in Cold War geopolitics, and in competition for land and resources in the Great Rift Valley. Armed, outside intervention is a recurring problem, especially in Congo (Kinshasa).

The roots of conflict in Central Africa are in the colonial era, in Cold War geopolitics, and in competition for land and resources in the Great Rift Valley. Armed, outside intervention is a recurring problem, especially in Congo (Kinshasa). Finding ways to sustainably exploit Central Africa’s resources for the benefit of Central African people is difficult.

Finding ways to sustainably exploit Central Africa’s resources for the benefit of Central African people is difficult. Change could come with increasing access to technology, which helps people earn better incomes and gain access to crucial information.

Change could come with increasing access to technology, which helps people earn better incomes and gain access to crucial information.