Southern Africa

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, hope is often a theme across Southern Africa (Figure 7.38). Rich deposits of diamonds, gold, chrome, copper, uranium, and coal are cause for optimism, as is the fact that at least in the country of South Africa, apartheid is gone, racial conflict has abated, and relative civil peace has brought substantial economic growth (see page 375). This justifiable optimism must be balanced with the fact that the region of Southern Africa faces significant agricultural, political, health, and development challenges that require enlightened leadership and a concerned participatory public.

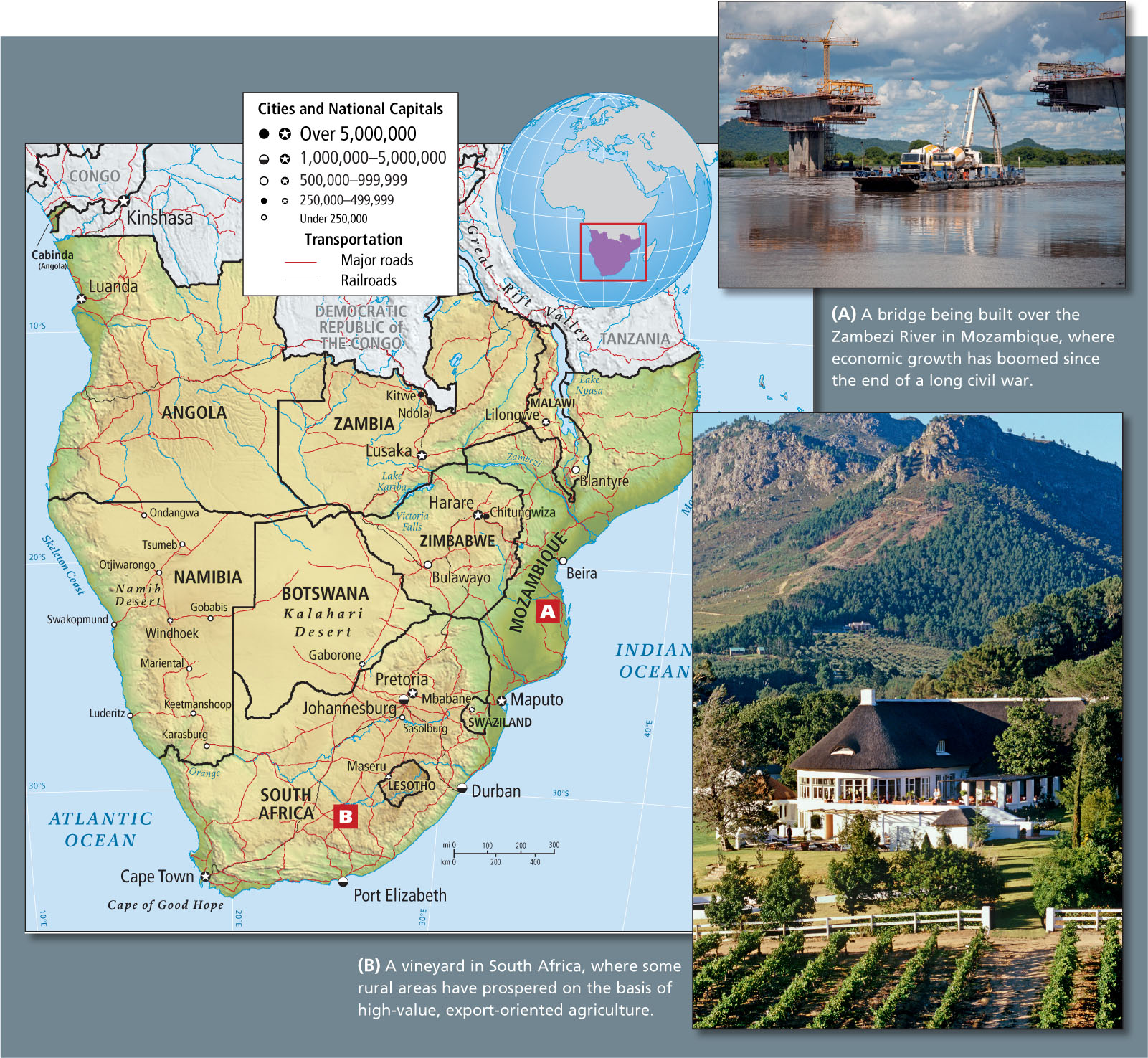

The region of Southern Africa is a plateau ringed on three sides by mountains and a narrow lowland coastal strip (see Figure 7.38). The Kalahari Desert lies at the center and the Namibian Desert along the southwest Atlantic coast, but for the most part, Southern Africa is a land of savannas and open woodlands. Its population density is low; the highest densities are found in South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Malawi (see Figure 7.22).

Rich Resources and Qualified Successes

South Africa is the wealthiest and perhaps the most stable country in the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. Some other countries in Southern Africa—Mozambique, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Angola—have been enjoying a measure of stability and economic growth as well, because of the development of mineral wealth. Even predominantly agricultural Malawi improved its economy markedly in the last decade, as did Zambia, which remains overly dependent on copper exports. Only Zimbabwe, once thought of as having great promise, has become a worrisome failed state, largely because of particularly ill-conceived race-based development strategies and bad governance. But the main cause for worry in the subregion remains the HIV-AIDS epidemic. Although the epidemic has ebbed a bit since 2005, in 2012, infection rates in Southern Africa remained 3 to 6 times higher than in any other region in the world. Between 10 and 30 percent of the adults in Southern Africa have HIV-AIDS, with the highest percentages of infection in Swaziland (30), Lesotho (28.2), South Africa (22.5), and Botswana (29.2). In all cases, women have a higher infection rate than men (see Figure 7.26; see also the discussion).

Angola and Mozambique are two former Portuguese colonies that both went through civil wars in order to gain independence. Marxist, Soviet-supported governments were on one side and rebels, supported by South Africa and the United States, were on the other. Mozambique ended its civil war in 1994; by 1996, its once-devastated economy had one of the highest rates of growth on the continent (7 percent in 2011; see Figure 7.38A).

Oil and Mineral Wealth

Angola became independent in 1974, but a post-independence civil war raged over rich mineral resources until 1998, when the warring parties signed a peace treaty. By 2009, Angola was the largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, and its oil revenues now constitute 85 percent of its GNI. Because of the fast pace of the development of these oil resources, Angola is now in a period of rapid growth and rapid inflation. Wealth disparity remains high and human well-being very low.

Mineral wealth is a mixed blessing. In Botswana, diamonds and other minerals brought wealth, but also brought an increase in income disparity. Botswana, once one of the most successful economies in sub-Saharan Africa, tries to portray itself in the best possible light, but the statistics on well-being that it provides are suspect, and certainly the burgeoning HIV-AIDS epidemic is thwarting Botswana’s economic development.

In Zimbabwe, chromium, gold, coal, nickel, platinum, and silver mining account for 40 percent of the country’s exports. Unfortunately, Zimbabwe’s economy has failed because of misguided advice from international lending agencies, the decline of commercial agriculture, and the flagrantly inept and illegitimate regime of Robert Mugabe.

Zambia’s rich copper resources have drawn investment and management by the Chinese, whose need to bring electricity to China’s rapidly industrializing cities has created a large demand for copper wire. The Chinese-run mines are efficiently managed, and production has soared, but very little of the profit reaches Zambian citizens. Despite the low wages of local miners, who earn just U.S.$50 a month, the Chinese mine managers are importing Chinese mine workers. Working conditions for both Zambian and Chinese laborers can be deadly. Zambian activists note that, as in colonial times, the extraction of Zambia’s resources is primarily benefiting foreign investors. Nonetheless, mine development has fueled consumerism, and Zambia now has multiple shopping malls where a widening range of products are available. Mobile phone use, especially by young adults, is widespread.

Food Insecurity in Southern Africa

The three interior countries of Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Zambia remain overwhelmingly rural. Agriculture and related food-processing industries form an important part of their economies and their exports, despite the growing role of mineral mining. Over the last two decades, agricultural productivity has fallen and food has been in seriously short supply. Both the global recession beginning in 2008 and the global commodity price spikes of 2009 share some of the blame for food shortages. The case of Malawi is illustrative.

A Case Study: Food Crisis in Malawi

Malawi has one of the world’s highest rural population densities. Eighty-five percent of Malawians are dependent on their wages as agricultural workers, as well as on their own food production, to feed their families. In 1980, there were about 6 million Malawians; by 2012 there were 16 million. In 1980, food production was still sufficient to feed the people, with surpluses left over for export. Land productivity then declined sharply because the fragile tropical soils, which need years of rest between plantings, had been forced to produce continuously to support plantation cultivation of tobacco, maize (corn), tea, and sugar for export. (Food production for export rather than for local consumption had been promoted after independence from Britain in 1964.) Meanwhile, smallholders, who lost land to large export producers, found themselves with insufficient land to allow for the necessary fallow periods, and their productivity fell as well.

By the 1990s, 86 percent of Malawi’s rural households had less than 5 acres (2 hectares) of land, yet they were responsible for producing nearly 70 percent of the food for internal consumption. HIV-AIDS kept skilled farmers out of the fields because they were sick, or had to tend the sick, so harvests shrank further. Malawi started to become more and more dependent on imported food. Between 2007 and 2009, the global food crisis and recession raised the cost of imported food. Additionally, in the spring of 2010, drought, which had been a problem for a number of years, was increasingly a threat, and food security for about 300,000 people in the far southern districts was precarious, with food deficits forecast to continue. The possibility of starvation was becoming very real. The case of Malawi, and the similar situations in Zimbabwe and Zambia, illustrate the point made in Chapter 1: Malnutrition and famine are often primarily the result of bad management and human foibles, rather than the result of the simple collapse of food production due to some natural event.

By 2011, partly because the natural environment rebounded, conditions were improving. Also important were USAID training in soil and moisture conservation and modest government aid from Australia that emphasized making innovative scientific research available to smallholders. Nevertheless, the lack of reliability of export prices places future food security at risk. [Source: Malawi Food Security Update. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

South Africa: A Model of Success for Southern Africa?

South Africa is a country of beautiful and striking vistas (see Figure 7.38B). Just inland from its long coastline, uplands and mountains afford dramatic views of the coast and the ocean. The interior is a high, rolling plateau reminiscent of the Great Plains in North America. South Africa is not tropical; it lies entirely within the midlatitudes and has consistently cool temperatures that range between 60°F and 70°F (16°C and 20°C). The extreme southern coastal area around Cape Town has a Mediterranean climate: cool and wet in the winter, dry in the summer.

About twice the areal size of Texas (whose population is 22 million), South Africa has 51 million people. Seventy-five percent of the people are of African descent, 14 percent of European descent, and 2 percent of Indian descent; the rest have mixed backgrounds. When Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, after more than 300 years of European colonization and 50 years of apartheid, he and Bishop Desmond Tutu, a prominent leader in the South African Anglican church (and a Nobel Peace Prize winner himself in 1984) insisted that in order to heal the racial divide, the country needed to face the reality of what had been done under apartheid (see Figure 7.15). Truth and Reconciliation Commissions asked those who had been brutal to step forward and admit what they had done in detail; those who spoke honestly were formally forgiven for their misdeeds.

South Africa’s colonial history and economic distinctiveness have been discussed. After apartheid, South Africa built competitive industries in communications, energy, transportation, and finance (it has a world-class stock market); it supplies goods and services to neighboring countries and its cities are modern and prosperous (Figure 7.39). In 2012, though, its ranking as one of the world’s top 10 emerging markets began to slip. Its economy still accounts for one-third of sub-Saharan Africa’s production, and other Southern African countries still receive the majority of their imports from South Africa (although China’s share is growing), but trade between South Africa and the European Union suffered during the EU debt crisis. South Africa’s position as the major market for products from all across Africa means that people everywhere in sub-Saharan Africa suffer when South Africa’s economy slumps.

Will South Africa be able to retain its position at the helm of economic development as sub-Saharan Africa moves into a more prosperous age? Progress is fragile, as illustrated by the global recession beginning in 2008 and lasting through 2012. During this period, South Africa suffered multiple blows: a decrease in the amount of aid from the United States and Europe and a hiatus in foreign investment; lower prices for its exports; and skyrocketing food prices. Strikes by miners left dozens dead; riots in the poorest parts of the country broke out over lack of employment and shortages of basic services like electricity and water. Jacob Zuma, a man with a record of corruption and a history of failed leadership in the HIV-AIDS epidemic, won a hotly contested presidential election. Will he be able to answer his detractors? The severe HIV-AIDS epidemic is bringing terrible losses to the young and educated who are the hope of the future, and the gap between rich and poor is wider now than it was at the end of apartheid.

Fortunately, the whole of sub-Saharan Africa appears to be on the verge of an era of self-guided development. No longer is the region inevitably tied to the success of South Africa, as was the case for so long. There is uncertainty as to whether South Africa will find the creative and courageous leadership necessary to regain its development momentum and move relatively smoothly into the information age of the twenty-first century.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Both optimism and worry are in the voices heard across Southern Africa—optimism because of the resilience and creativity of its citizens and rich resources that are gradually improving well-being for most of the people; worry because of disease, especially HIV-AIDS, and poor leadership and corruption in some countries.

Both optimism and worry are in the voices heard across Southern Africa—optimism because of the resilience and creativity of its citizens and rich resources that are gradually improving well-being for most of the people; worry because of disease, especially HIV-AIDS, and poor leadership and corruption in some countries. Foreign access to the resources of countries in the northern parts of Southern Africa could work to the ultimate disadvantage of these countries.

Foreign access to the resources of countries in the northern parts of Southern Africa could work to the ultimate disadvantage of these countries. The food crisis in Malawi, brought on by a complex set of causes—some a legacy of the colonial development of cash-crop agricultural exports, some connected to changing global markets, and some related to inappropriate cultivation practices—is slowly turning around, with the help of judicious, not lavish, aid from developed countries.

The food crisis in Malawi, brought on by a complex set of causes—some a legacy of the colonial development of cash-crop agricultural exports, some connected to changing global markets, and some related to inappropriate cultivation practices—is slowly turning around, with the help of judicious, not lavish, aid from developed countries. Racial reconciliation, outstanding post-apartheid leadership, and rich resources helped make South Africa a leader in Southern Africa. A more recent long series of misfortunes, some self-inflicted, has brought South Africa to a precarious position. The country’s potential to lead sub-Saharan Africa into a more prosperous age is increasingly uncertain.

Racial reconciliation, outstanding post-apartheid leadership, and rich resources helped make South Africa a leader in Southern Africa. A more recent long series of misfortunes, some self-inflicted, has brought South Africa to a precarious position. The country’s potential to lead sub-Saharan Africa into a more prosperous age is increasingly uncertain.