Physical Patterns

The African continent is big—the second largest after Asia and about 2 million square miles (5.2 million square kilometers) bigger than North America. But Africa’s great size is not matched by its surface complexity. Africa has no major mountain ranges, but it does have several high volcanic peaks, including Mount Kilimanjaro (19,324 feet [5890 meters] high; see Figure 7.1B) and Mount Kenya (17,057 feet [5199 meters] high). At their peaks, both have permanent snow and ice, though these features have shrunk dramatically due to global climate change and associated local environmental changes. More than one-fourth of the African continent is covered by the Sahara Desert, which reaches to the edge of the Mediterranean Sea.

Landforms

The surface of the continent of Africa can be envisioned as a raised platform, or plateau, bordered by fairly narrow and uniform coastal lowlands. The platform slopes downward to the north; it has an upland region with several high peaks in the southeast, and lower uplands in the northwest. The steep escarpments (long, high cliffs) between plateau and coast have obstructed transportation and hindered connections to the outside world. Africa’s lengthy, uniform coastlines provide few natural harbors, Cape Town in South Africa being an exception (see Figure 7.1E).

Geologists usually place Africa at the center of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea (see Figure 1.25). As landmasses broke off from Africa and moved away—North America to the northwest, South America to the west, and India to the northeast—Africa readjusted its position only slightly. Because its shift was so small, it did not pile up long, linear mountain ranges, as did the other continents when their plates collided with one another (see page 44).

Africa continues to break apart along its eastern flank. There the Arabian Plate has already split away and drifted to the northeast, leaving the Red Sea, which separates Africa and Asia. Another split, known as the Great Rift Valley, extends south from the Red Sea more than 2000 miles (3200 kilometers) (see Figure 7.1C). In the future, Africa is expected to split again along these rifts.

Climate and vegetation

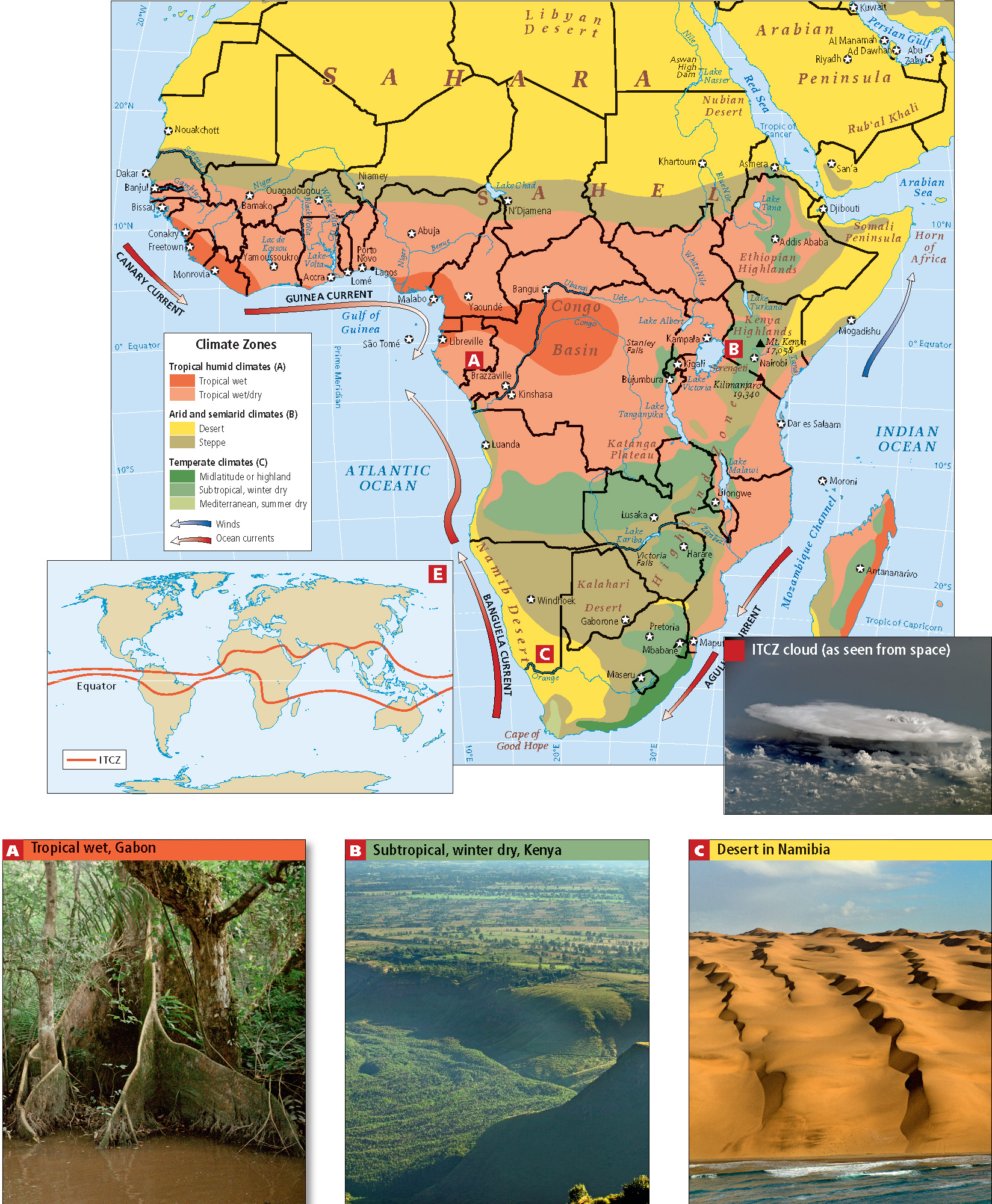

Most of sub-Saharan Africa has a tropical climate (see Figure 7.5 map). Average temperatures generally stay above 64°F (18°C) year-round everywhere except at the more temperate southern tip of the continent and in the cooler upland zones (hills, mountains, high plateaus). Seasonal climates in Africa differ more by the amount of rainfall than by temperature.

intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly around the equator; warm winds from both north and south converge at the ITCZ, pushing air upward and causing copious rainfall

The ITCZ shifts north and south seasonally, generally following the area of Earth’s surface that has the highest average temperature at any given time. Thus, during the height of summer in the Southern Hemisphere in January, the ITCZ might bring rain far enough south to water the dry grasslands, or steppes, of Botswana. During the height of summer in the Northern Hemisphere in August, the ITCZ brings rain as far north as the southern fringes of the Sahara, to the area called the Sahel, a band of arid grassland 200 to 400 miles (320 to 640 kilometers) wide that runs east-west along the southern edge of the Sahara (see Figure 7.5). At roughly 30° N latitude (the Sahara) and 30° S latitude (the Namib and Kalahari deserts) the air, which has dried out during its passage, descends, forming a subtropical high-pressure zone that shuts out lighter, warmer, moister air. As a result of this system (which is in no way precise), deserts tend to be found in Africa (and on other continents) in these zones about 30 degrees north and south of the equator.

The tropical wet climates that support equatorial rain forests are bordered on the north, east, and south by seasonally wet/dry subtropical woodlands (see Figure 7.5B). These give way to moist tropical savannas or steppes, where tall grasses and trees intermingle in a semiarid environment. These tropical wet, wet/dry, and steppe climates have provided suitable land for different types of agriculture for thousands of years, but the amount of moisture available in each of these climates can vary greatly, in cycles that are decades long. Farther to the north and south lie the true desert zones of the Sahara and the Namib and Kalahari (see Figure 7.5C). This banded pattern of African ecosystems is modified in many areas by elevation and wind patterns.

Horn of Africa the triangular peninsula that juts out from northeastern Africa below the Red Sea and wraps around the Arabian Peninsula