Environmental Issues

Geographic Insight 1

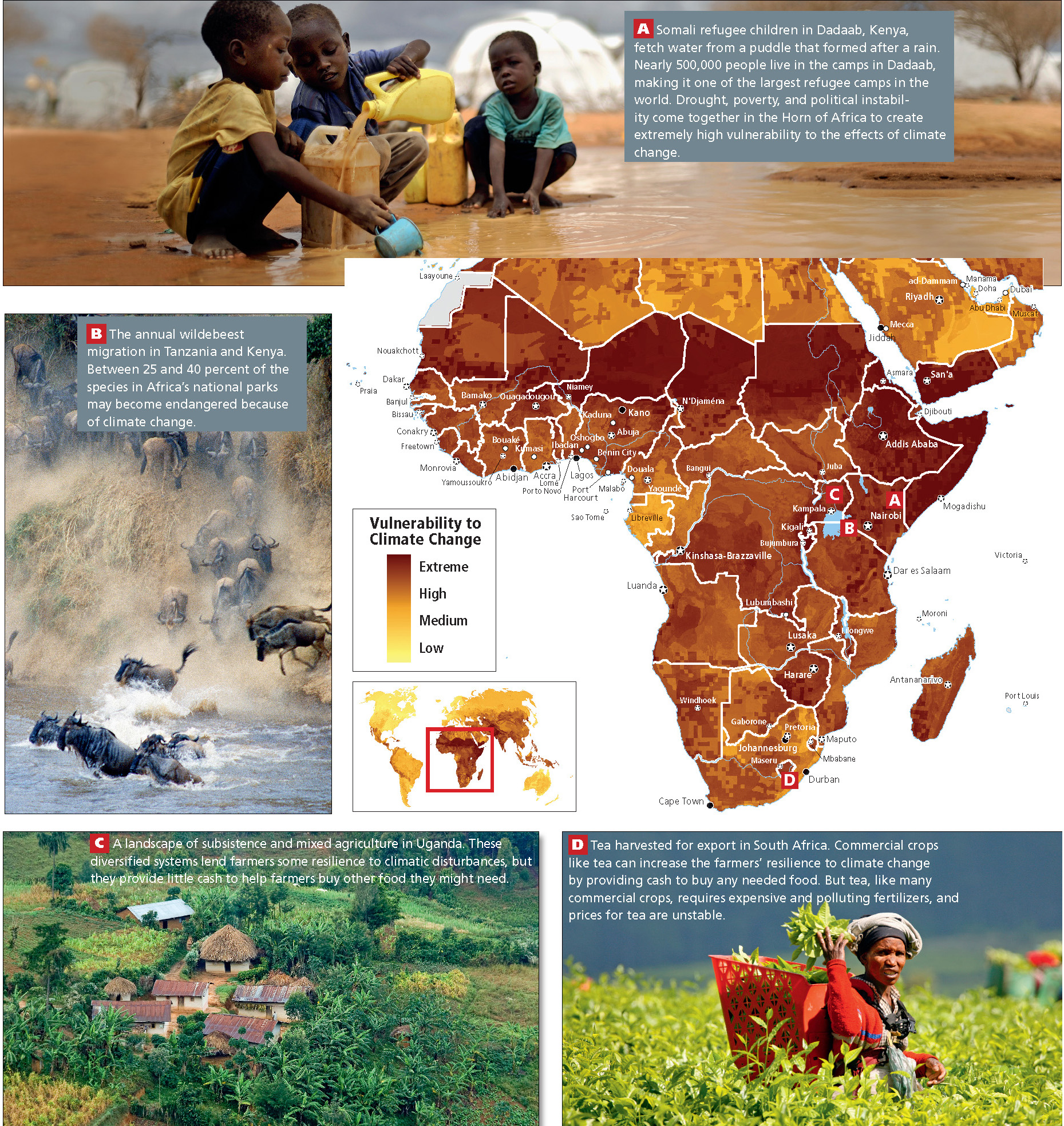

Climate Change, Food, and Water: Sub-Saharan Africa is particularly vulnerable to climate change because subsistence occupations are sensitive to even slight variations in temperature, rainfall, and water availability. In large part because of poverty, political instability, and having little access to cash, the region does not have much resilience to the effects of climate change.

While Africans have generally contributed very little to the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, deforestation in Africa by ordinary people and by commercial entities that operate globally is amplifying global climate change. Because of Africa’s poverty, its people are much less able to adapt to climate change than those who generate most greenhouse gases. Even so, many Africans are developing strategies to cope with uncertainties related to the region’s changing climate.  158. DISAPPEARING GLACIERS ON MT. KILIMANJARO RAISE ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

158. DISAPPEARING GLACIERS ON MT. KILIMANJARO RAISE ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

Deforestation and Climate Change

carbon sequestration the removal and storage of carbon taken from the atmosphere

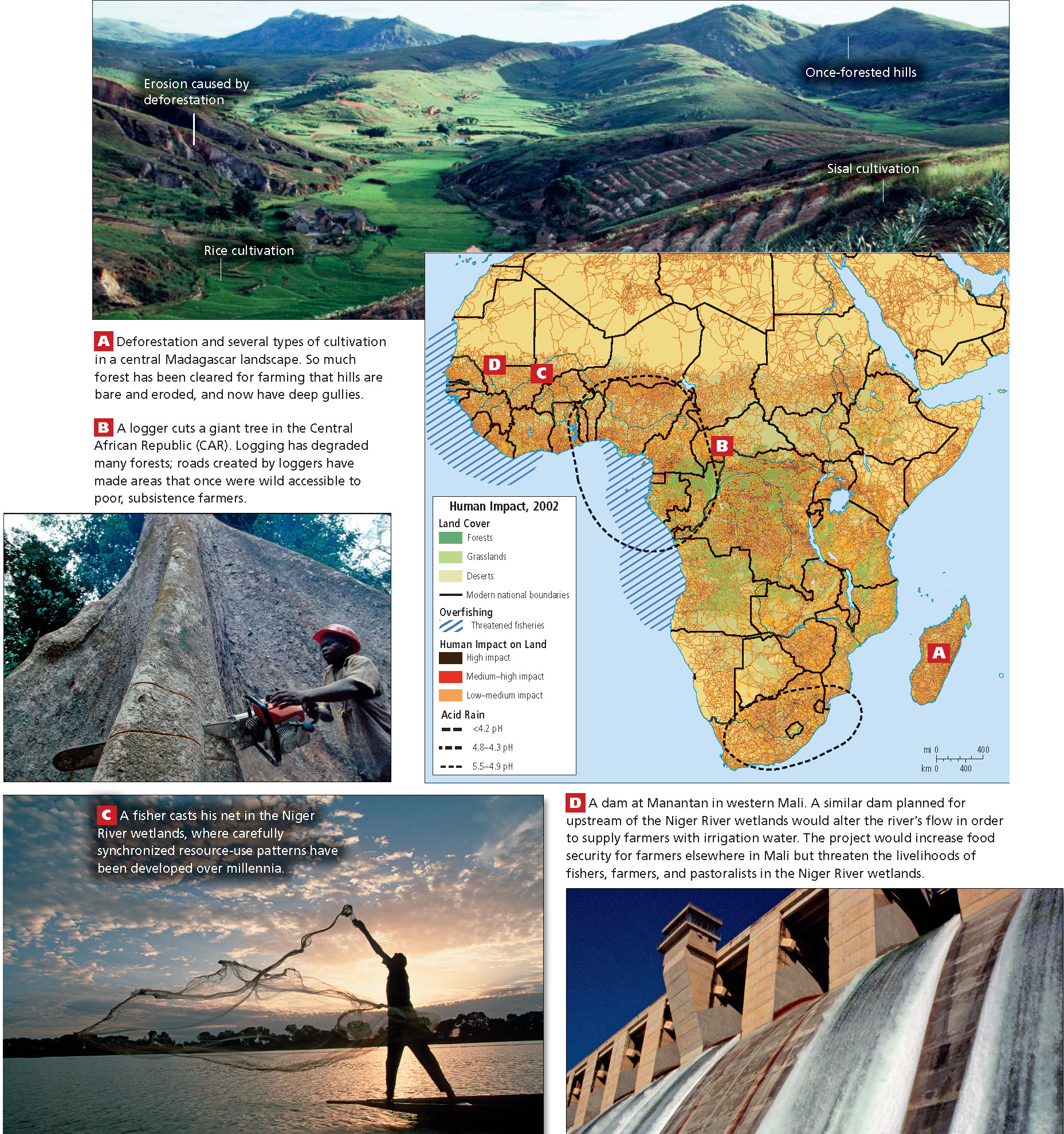

African countries lead the world in the rate of deforestation, the percentage of total forest area lost. Of the eight countries that had the world’s highest rates of deforestation between 1990 and 2005, six are in sub-Saharan Africa (Burundi, Togo, Nigeria, Benin, Uganda, and Ghana). This deforestation constitutes a major human environmental impact across the region (Figure 7.6). The countries that have the most emissions from deforestation are Brazil and Indonesia, but Nigeria and Congo (Kinshasa) have the third and fourth most, respectively.  168. PLAN TO CLEAR-CUT UGANDAN FOREST RESERVE FOR GROWING SUGAR CANE SPARKS CONTROVERSY

168. PLAN TO CLEAR-CUT UGANDAN FOREST RESERVE FOR GROWING SUGAR CANE SPARKS CONTROVERSY

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about human impact on the biosphere in sub-Saharan Africa, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Other than the caption, what clues are there to suggest this landscape has been cleared of forest?

Other than the caption, what clues are there to suggest this landscape has been cleared of forest?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What about this photo suggests that the trees being logged are from old-growth forests?

What about this photo suggests that the trees being logged are from old-growth forests?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What about the fishing methods depicted in the photo suggests that catches are fairly small in size?

What about the fishing methods depicted in the photo suggests that catches are fairly small in size?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

VIGNETTE

Liberian environmental activist Silas Siakor is an affable and unassuming fellow. But his casual style conceals a fierce dedication to his homeland and a remarkable sleuthing ability. At great personal risk, Siakor uncovered evidence that 17 international logging companies were bribing Liberia’s then-president, Charles Taylor, with cash and guns. Taylor allowed the companies to illegally log Liberia’s forests, which are home to many endangered species including forest elephants and chimpanzees. In return, the companies paid cash and provided weapons that Taylor used to equip his personal armies. Made up largely of kidnapped and enslaved children, Taylor’s armies fought those of other Liberian warlords in a 14-year civil war that took the lives of 150,000 civilians. The war also spilled over into neighboring Sierra Leone, where another 75,000 people died. Meanwhile, the logging companies—based in Europe, China, and Southeast Asia—reaped huge fortunes from the tropical forests.  175. ‘EZRA,’ TRAGIC TALE OF CHILD SOLDIERS IN AFRICA

175. ‘EZRA,’ TRAGIC TALE OF CHILD SOLDIERS IN AFRICA

Silas Siakor pulled together publicly available information that had been previously ignored by the international community and information provided by informed ordinary citizens in ports, villages, and lumber companies. He prepared a clear, well-documented report substantiating the massive logging fraud. In response to Siakor’s report, the UN Security Council voted to impose sanctions to stop the timber trade and prosecute some of the people involved. Charles Taylor fled to Nigeria, but in 2006 he was turned over to face a war crimes tribunal in The Hague, Netherlands. In April of 2012 Taylor received a 50-year sentence.

Democratic elections followed in Liberia in 2006, after which Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf took office as Africa’s first elected woman president. In a move that was bold—given the poverty and political instability of her country—she cancelled all contracts with timber companies, pending a revision of Liberian forestry law. By 2012, President Johnson-Sirleaf was herself being audited by the global Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) for $8 billion worth of questionable resource contracts. Liberia, now calculated to be resource rich, is the first African country to submit to the EITI anticorruption audits. [Sources: Goldman Environmental Prize, National Public Radio, and Silas Siakor. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

The story of Silas Siakor and Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf illustrates how Liberia, like much of this region, is still in the process of developing strong democratic institutions that can sustainably develop the country’s resources and use them to the benefit of its citizens.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The value of Agroforestry

A strong promoter of agroforestry is the Green Belt Movement, founded by Dr. Wangari Maathai of Kenya. The Green Belt Movement helps rural women plant trees for use as fuelwood and to reduce soil erosion. The movement grew from Maathai’s belief that a healthy environment is essential for democracy to flourish. Thirty years and 30 million trees after she began, Maathai was awarded the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her contributions to sustainable development, democracy, and peace.

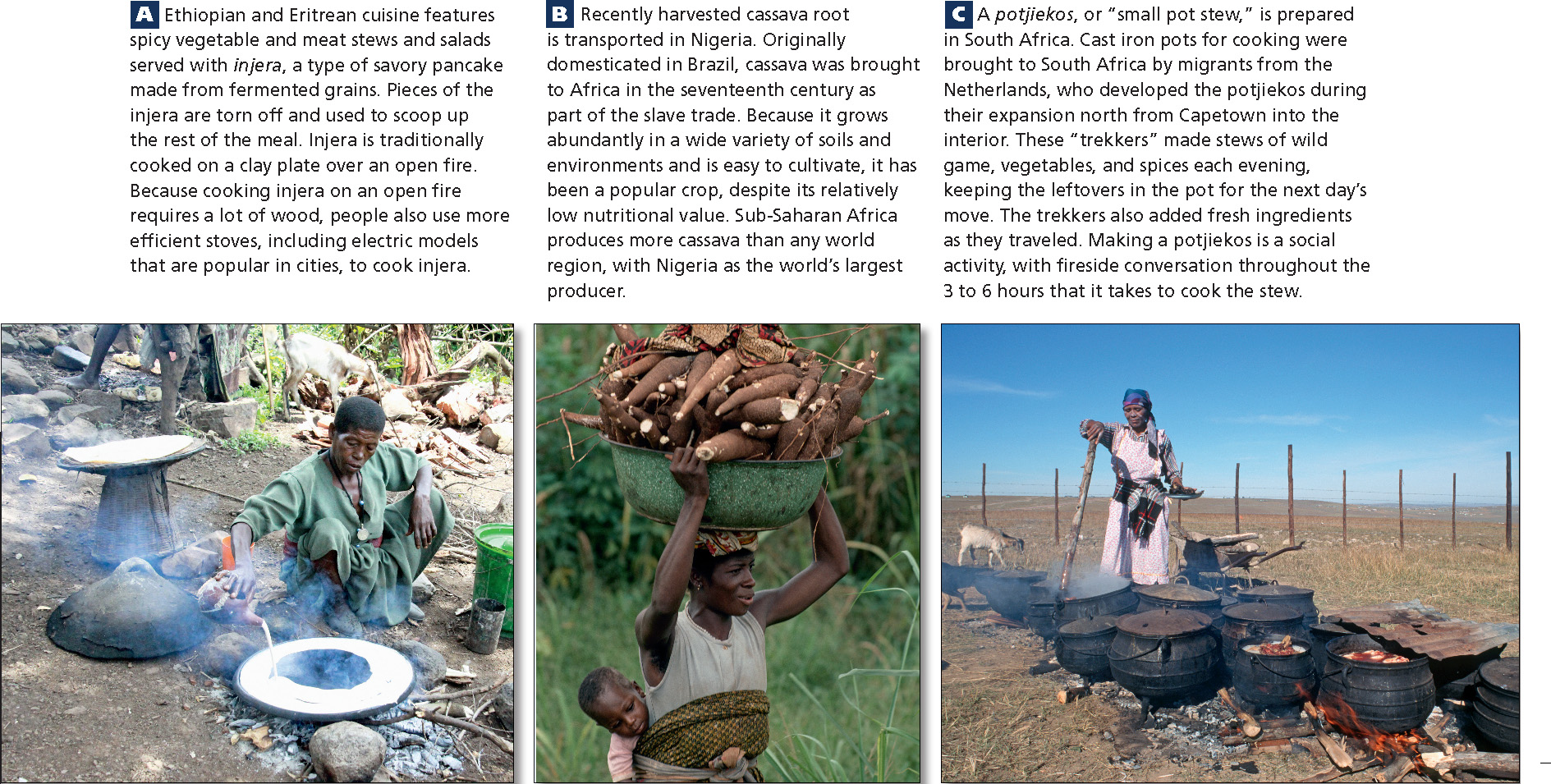

Most of Africa’s deforestation is driven by the growing demand for farmland and fuelwood, although logging by international timber companies is also increasing. Africans use wood (or charcoal made from wood) to supply nearly all their domestic energy (see Figure 7.6 A, B). Wood remains the cheapest fuel available, in part because of African traditions that consider forests to be a free resource held in common. Even in Nigeria, a major oil producer, most people use fuelwood because they cannot afford petroleum products. Across the region, not only are charcoal prices rising as the forests disappear, but the smoke from the charcoal is causing asthma and other respiratory problems, as well as creating greenhouse gases.

In Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, women are engaged in a for-profit project that combines new technology with traditional crops and crop rotation techniques to create a sustainable fuel and food preparation system. The aim is to shift the 1.2 million inhabitants of Maputo from relying on charcoal—made from the disappearing old-growth forests in the north of the country—to using ethanol made from the roots of the cassava plant grown by the women on their own land. Newly developed small metal cookstoves run on the cassava-based ethanol. The project also encourages farmers to rotate their crops to preserve soil fertility. In any given year, a third of the the land is planted in a cash crop of cassava used to make ethanol and the rest of the land is used to plant multiple-species food gardens.

The multifaceted stove/ethanol/cassava pilot project in Maputo is funded by four American firms that hope to replicate it elsewhere around the world. They want to save the forests, relieve fuel shortages, halt rising fuelwood prices, and alleviate air pollution, while simultaneously improving food security and creating local enterprises: those that can build the innovative cookstoves and those that can produce cassava-based ethanol.

agroforestry growing economically useful crops of trees on farms, along with the usual plants and crops, to reduce dependence on trees from non-farmed forests and to provide income to the farmer

Agricultural Systems, Food, Water, and vulnerability to Climate Change

Agricultural systems in Africa are undergoing a rapid transition from being oriented around subsistence farming to being centered on commercial farming. Unfortunately, this change is happening in an era when the advantages of traditional agriculture are only beginning to be appreciated. Thus the social and environmental effects of turning rapidly to commercial production are not fully understood, especially given the as yet little-known ecological impacts of climate change.

Traditional Agriculture

subsistence agriculture farming that provides food for only the farmer’s family and is usually done on small farms

mixed agriculture farming that involves raising a variety of crops and animals on a single farm, often to take advantage of several environmental riches

shifting cultivation a productive system of agriculture in which small plots are cleared in forestlands, the dried brush is burned to release nutrients, and the clearings are planted with multiple species; each plot is used for only 2 or 3 years and then abandoned for many years of regrowth

These traditional, subsistence, mixed, and shifting cultivation food-acquisition techniques have advantages and disadvantages in a world of climate change. All of these closely related forms of agriculture provide a diverse array of strategies for coping with the changes in temperature and rainfall that climate change may bring. As in much of sub-Saharan Africa, traditional Nigerian farmers (usually women) grow complex tropical gardens, often with 50 or more species of plants at one time. Some of the plants can handle drought, while others can withstand intense rain or heat.

However, the subsistence nature of most African farming can also leave families without much cash. If harvests are too low to provide surplus that can be sold, and hunting and gathering fail to provide supplementary food for the family, there may be insufficient money to buy food. While such situations can lead to famine, it is important to note that the most serious famines in Africa have occurred not because of low harvests but rather because of political instability that disrupts economies and food growing and distribution systems.  162. FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM AIMS TO OPEN DOORS FOR AFRICAN WOMEN IN AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

162. FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM AIMS TO OPEN DOORS FOR AFRICAN WOMEN IN AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

Commercial Agriculture

commercial agriculture farming in which crops are grown deliberately for cash rather than solely as food for the farm family

However, some of the most common commercial crops, such as peanuts, cacao beans (used for making chocolate), rice, tea, and coffee, are often less adapted to environments outside their native range (Figure 7.8D). They are more likely to produce smaller yields if temperatures increase or water becomes scarce. Moreover, to maximize profits, these crops are often grown in large fields of only a single plant species. This can leave crops vulnerable to pests; if crops fail, farmers have no other garden foods to rely on. The potential for commercial agriculture to help farmers adapt to the uncertainties of global climate change is also limited by the instability of prices for commercial crops. Prices can rise or fall dramatically from year to year because of overproduction or crop failures both in Africa and abroad.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about vulnerability to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

How is poverty evident in this photo?

How is poverty evident in this photo?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What caused the death of many wildebeest in 2007?

What caused the death of many wildebeest in 2007?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How is agricultural diversity illustrated in this photo?

How is agricultural diversity illustrated in this photo?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What kind of climate change in Africa most often causes a reduced yield for a crop like tea?

What kind of climate change in Africa most often causes a reduced yield for a crop like tea?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Commercial agriculture—whether small scale, locally managed, or large scale—owned and operated by international corporations (agribusiness), demands permanently cleared fields. But in the tropics, because soil fertility declines rapidly once the trees are removed, commercial crops are more likely to fail even under ideal climatic conditions. Chemical fertilizers can compensate for this loss, but are often too expensive for ordinary farmers, and when used repeatedly by agribusiness, may lose their effectiveness. Moreover, rains almost always wash much of the fertilizer into nearby waterways, thus polluting them. This may ultimately hurt farmers and fishers by spoiling drinking water and reducing the quantity of available fish, which are important sources of protein for rural people.

These aspects of commercial agricultural systems make them poorly adapted even to the most ideal climatic conditions, let alone the hotter and more drought-prone environments that climate change may bring. Foreign agricultural “experts” who often push commercial systems can be woefully ignorant of local conditions and the value of local cultivation techniques. For example, in Nigeria, it is women who grow most of the food for family consumption and who are guardians of the knowledge that makes Nigeria’s traditional farming systems work. However, women are rarely included or even consulted by the foreign experts who promote commercial agricultural development projects. At best, women are employed as field laborers. Consequently, diverse subsistence agricultural systems based on numerous plant species and deep knowledge about the environment have been replaced by less stable commercial systems that are based on a single plant species, and that do not take into account the skills and knowledge base of women.

Agricultural scientists recently began to recognize past mistakes and have been trying to incorporate the traditional knowledge of African farmers, female and male, into more diverse commercial agriculture systems. For example, scientists at Nigeria’s International Institute for Tropical Agriculture are developing cultivation systems that, like traditional systems, use many species of plants that help each other cope with varying climatic conditions. Most of these systems are designed for both subsistence and commercial agriculture, and thus can give families both a stable food supply and cash to help them ride out crop failures and pay school fees for their children (see Figure 7.8C).

Water Resources, Irrigation, and Water Management Alternatives

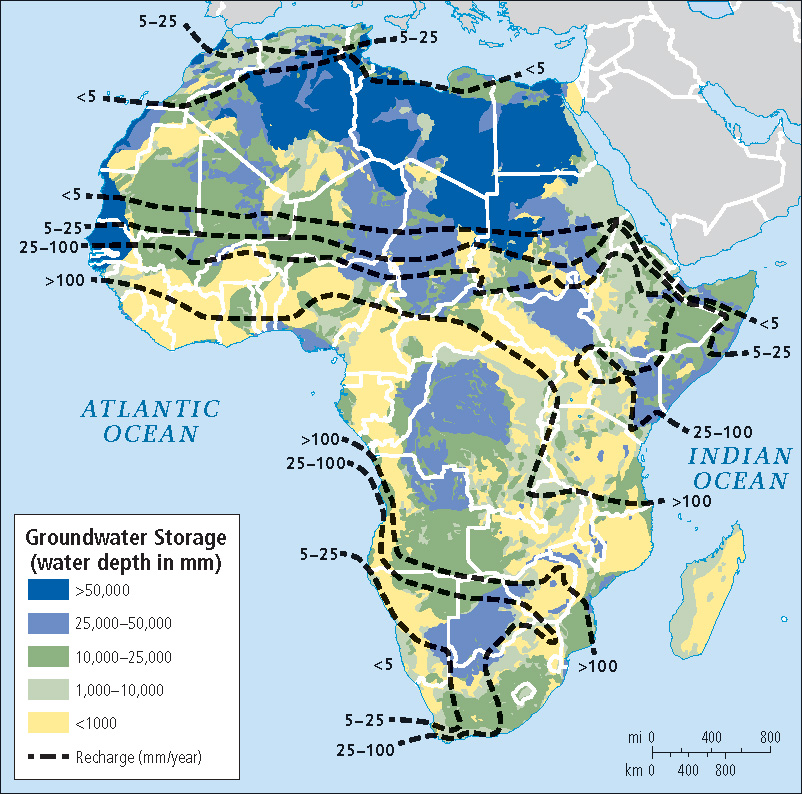

Although sub-Saharan Africa has a large wet tropical zone, much of the region is seasonally dry (see the Figure 7.5 map); and because climate change is likely to result in changing rainfall patterns, the areas that have freshwater deficits are expected to increase, with a related increase in refugees (see Figure 7.8A). In water-deficit conditions, many people look to irrigation to provide more stability to agricultural systems (see Figure 7.6D). But does Africa have sufficient groundwater resources to supply irrigation systems plus fill all the other demands for fresh water by its modernizing societies? Recall that per capita water use expands exponentially with development (see Chapter 1).

New Groundwater Discoveries

groundwater water naturally stored in aquifers as long as 5000 years ago during wetter climate conditions

New Large- and Small-Scale Irrigation Projects

Government officials continue to favor large-scale irrigation projects to address the need for increased food supplies in the face of present and future water scarcity. Africa has a number of major rivers—the Nile, the Congo, the Zambezi, and the Limpopo—and climate change will affect all of them. Here we focus on the Niger, one of Africa’s most important rivers, which flows through several very different ecological zones. The Niger rises in the tropical wet Guinea Highlands and carries summer floodwaters northeast into the normally arid lowlands of Mali and Niger (see the Figure 7.5 map and Figure 7.6C, D). There the waters spread out into lakes and streams that nourish wetlands. For a few months of the year (June through September), the wetlands ensure the livelihoods of millions of fishers, farmers, and pastoralists. These people share the territory in carefully synchronized patterns of land use that have survived for millennia. Wetlands along the Niger produce 8 times more plant matter per acre than the average wheat field. They provide seasonal pasture for millions of domesticated animals, and serve as an important habitat for wildlife.

The governments of Mali and Niger now want to dam the Niger River and channel its water into irrigated agribusiness projects that they hope will help feed the more than 26 million people in both countries. However, the dams will forever change the seasonal rise and fall of the river. The irrigation systems may also pose a threat to human health. Systems that rely on surface storage not only lose a great deal of water through evaporation and leakage, the standing pools of water they create often breed mosquitoes that spread tropical diseases, such as malaria, and harbor the snails that host schistosomiasis, a debilitating parasite that enters the skin of humans who spend time standing in still water to fish or do other chores.

Many smaller-scale alternatives are available. In some parts of Senegal, for example, farmers are using hand- or foot-powered pumps to bring water from rivers or ponds directly to the individual plants that need it. This is in some ways a more modern version of traditional African irrigation practices whereby water is delivered directly to the roots of the plants by human, often female, water brigades. Smaller-scale projects provide the same protection against drought that larger systems offer, but are much cheaper and simpler to operate for small farmers. They also avoid the social dislocation and ecological disruption of larger projects. Already in successful use for 15 years, these low-tech pumps will help farmers adjust to the drier conditions that may come with climate change.

Herding and Desertification

pastoralism a way of life based on herding; practiced primarily on savannas, on desert margins, or in the mixture of grass and shrubs called open bush

Many traditional herding areas in Africa are now undergoing desertification, the process by which arid conditions spread to areas that were previously moist (see Chapter 6). The drying out is often the result of the loss of native vegetation; traditional herding may be partially to blame, but economic development schemes that encourage cattle raising are also at fault. Cattle need more water and forage than do traditional herding animals and so can place greater stress on native grasslands than goats or camels do. Agricultural intensification in the Sahel also contributes to desertification, as scarce water resources are diverted to irrigation, leaving dry, vegetation-less soils exposed to wind erosion.

Over the last century, desertification has shifted the Sahel to the south. For example, the World Geographic Atlas in 1953 showed Lake Chad situated in a forest well south of the southern edge of the Sahel. By 1998, the Sahara itself was encroaching on Lake Chad (see the Figure 7.5 map) and the lake had shrunk to a tenth of the area it occupied in 1953.

Wildlife and Climate Change

Africa’s world-renowned wildlife faces multiple threats from both human and natural forces, all of which could become more severe with increases in global climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a body of scientists tasked by the United Nations with assessing scientific information relevant to understanding climate change, estimates that 25 to 40 percent of the species in Africa’s national parks may become endangered as a result of climate change.

Wildlife managers are developing new management techniques to help animals survive. For example, one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on the planet took a tragic turn in 2007. The annual 1800-mile-long (2900-kilometer-long) natural migration of more than a million wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles in Kenya’s Maasai Mara game reserve requires animals to traverse the Mara River. In the best of times, this is a difficult migration that usually results in a thousand or so animals drowning. In the past, the park’s managers have taken a hands-off approach to the migration, considering the losses normal. However, in 2007, extremely heavy rains, possibly related to global climate change, swelled the Mara River to record levels. When the animals tried to cross, 15,000 drowned (see Figure 7.8B). Park managers are now taking a more active role in helping the migrating animals cope with unusual climatic conditions that may worsen with climate change. This may involve stopping animals from attempting a river crossing or directing them to a safer crossing.

169. PROTECTING NATURE IN GUINEA COLLIDES WITH HUMAN NEEDS

169. PROTECTING NATURE IN GUINEA COLLIDES WITH HUMAN NEEDS

Farmers’ dependence on hunting wild game (bushmeat) for part of their food and income is already a major threat to wildlife in much of Africa. For example, farmers who need food or extra income are killing endangered species, such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and especially elephants, in record numbers (Figure 7.10C). If crop harvests are diminished by global climate change, many farmers will become even more dependent on bushmeat and on income from selling contraband, such as ivory. The threat to wild populations of various species has led to calls to expand and establish new protected areas for wildlife.

Africa’s national parks constitute one-third of the world’s preserved national parkland. The parks are struggling to deal with poaching (illegal hunting) within the park boundaries by members of surrounding communities. Poaching is often fueled by demand outside Africa for exotic animal parts (tusks, hooves, penises) as medicines and aphrodisiacs, especially in Asia, where efforts to educate consumers about the damage done by their purchases are only beginning.

Some parks are now using profits from ecotourism to fund development in nearby communities that previously depended in part on poaching. For example, in 1985, wildlife poaching threatened the animal population in Zambia’s Kasanka National Park. Park managers decided to generate employment for the villagers through tourism-related activities. They built tourist lodges and wildlife-viewing infrastructure and started cottage industries to make products to sell to the tourists. Funding also goes to local clinics and schools, and students are included in research projects within the park. Local farmers have expanded into alternative livelihoods, such as beekeeping and agroforestry. Today, poaching in Kasanka is very low, its wildlife populations are booming, tourism is growing, and local communities have an ongoing stake in the park’s success. Sub-Saharan Africa’s rich array of animals has long played an economic role in daily life. Three species are discussed in Figure 7.10.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The surface of the continent of Africa can be envisioned as a raised platform, or plateau, bordered by fairly narrow and uniform coastal lowlands.

The surface of the continent of Africa can be envisioned as a raised platform, or plateau, bordered by fairly narrow and uniform coastal lowlands. Most of sub-Saharan Africa has a tropical wet or wet/dry climate, except at the southern tip and in the cooler uplands. Seasonal climates in Africa differ more by the amount of rainfall than by temperature.

Most of sub-Saharan Africa has a tropical wet or wet/dry climate, except at the southern tip and in the cooler uplands. Seasonal climates in Africa differ more by the amount of rainfall than by temperature. Most rainfall comes to Africa by way of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly around the equator. The effects of desertification are most dramatic in the region called the Sahel.

Most rainfall comes to Africa by way of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly around the equator. The effects of desertification are most dramatic in the region called the Sahel. Geographic Insight 1Climate Change, Food, and Water Africa’s food production systems, which are still largely subsistence-based but include some mixed agriculture and hunting, are threatened by climate change. The effects of climate change are made worse by poverty and political instability.

Geographic Insight 1Climate Change, Food, and Water Africa’s food production systems, which are still largely subsistence-based but include some mixed agriculture and hunting, are threatened by climate change. The effects of climate change are made worse by poverty and political instability. The primary way in which sub-Saharan Africa contributes to CO2 emissions and potential climate change is through deforestation. Much of Africa’s deforestation is driven by the growing demand for farmland and fuelwood, but corruption on the part of local authorities and international timber companies also plays a role.

The primary way in which sub-Saharan Africa contributes to CO2 emissions and potential climate change is through deforestation. Much of Africa’s deforestation is driven by the growing demand for farmland and fuelwood, but corruption on the part of local authorities and international timber companies also plays a role. Long-standing physical challenges, such as deforestation, desertification, and increasing water scarcity, have had a major impact on sub-Saharan Africa’s ecosystems. Commercial food production for Africa’s cities has many ecological drawbacks. These challenges are likely to increase with climate change.

Long-standing physical challenges, such as deforestation, desertification, and increasing water scarcity, have had a major impact on sub-Saharan Africa’s ecosystems. Commercial food production for Africa’s cities has many ecological drawbacks. These challenges are likely to increase with climate change. Newly discovered groundwater resources hold promise for alleviating some of Africa’s water scarcities.

Newly discovered groundwater resources hold promise for alleviating some of Africa’s water scarcities.