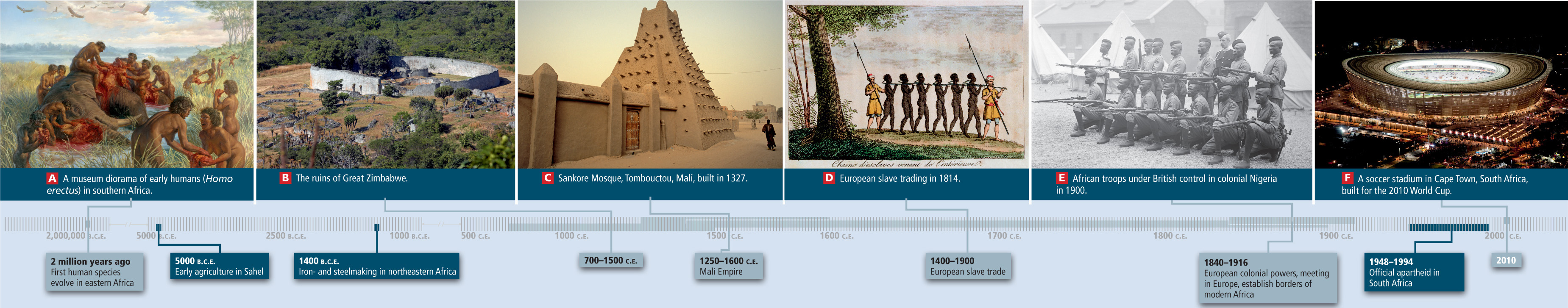

Human Patterns over Time

Africa’s rich past has often been misunderstood and dismissed by people from outside the region. European slave traders and colonizers called Africa the Dark Continent and assumed it was a place where little of significance in human history had occurred. The substantial and elegantly planned cities of Benin in western Africa, Djenné in the Niger River basin, and Loango in the Congo Basin, which European explorers encountered in the 1500s, never became part of Europe’s image of Africa. Even today, most people outside the continent are unaware of Africa’s internal history or its contributions to world civilization, let alone its role in the very emergence of humankind.

The Peopling of Africa and Beyond

Africa is the original home of humans (Figure 7.11A). It was probably in eastern Africa (in what are today the highlands of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda) that the first human species (Homo erectus) evolved more than 2 million years ago. Homo erectus differed anatomically from humans today. These early, tool-making humans ventured out of Africa, reaching north of the Caspian Sea and beyond as early as 1.8 million years ago. Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved about 250,000 years ago from earlier hominoids (probably Homo erectus) in eastern Africa. Like the migrations of earlier human species, those of modern humans radiated out of Africa, first toward the eastern Mediterranean (Homo sapiens reached the eastern Mediterranean about 90,000 years ago), then spreading across mainland and island Asia and only later turning west into Europe. Eventually, after coexisting in Eurasia and Europe with earlier dispersions of Homo erectus and other Homo species (all originating in Africa), Homo sapiens outcompeted them all.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of sub-Saharan Africa, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What are the clues in the picture that food many have been a source of conflict between early humans and between humans and other animals?

What are the clues in the picture that food many have been a source of conflict between early humans and between humans and other animals?

| A. |

| B. |

Question

Beyond the central fortlike structure, describe any further evidence of human habitation.

Beyond the central fortlike structure, describe any further evidence of human habitation.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What does the existence of a mosque in Mali in 1327 indicate about the geography of trading patterns in this part of Africa?

What does the existence of a mosque in Mali in 1327 indicate about the geography of trading patterns in this part of Africa?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is the evidence of European involvement in the slave trade in this image?

What is the evidence of European involvement in the slave trade in this image?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

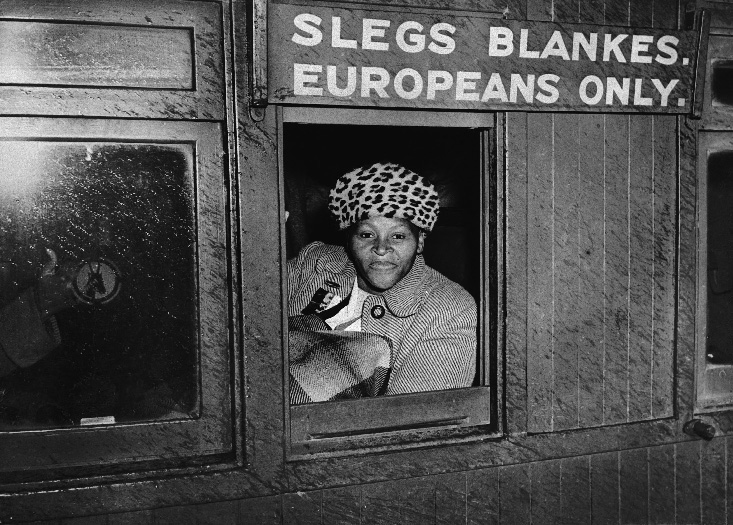

What about this photo suggests hierarchies of status in British colonial Africa?

What about this photo suggests hierarchies of status in British colonial Africa?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What about this stadium conveys the wealth and Westernization of South Africa?

What about this stadium conveys the wealth and Westernization of South Africa?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Early Agriculture, Industry, and Trade in Africa

In Africa, people began to cultivate plants as far back as 7000 years ago in the Sahel and the highlands of present-day Sudan and Ethiopia. Agriculture was brought south to equatorial Africa 2500 years ago and to southern Africa about 1500 years ago. Trade routes spanned the African continent, extending north to Egypt and Rome and east to India and China. Gold, elephant tusks, and timber from tropical Africa were exchanged for salt, textiles, beads, and a wide variety of other goods.

About 3400 years ago, people in the vicinity of Lake Victoria learned how to smelt iron and make steel. By 700 c.e., when Europe was still recovering from the collapse of the Roman Empire, a remarkable civilization with advanced agriculture, iron production, and gold-mining technology had developed in the highlands of southeastern Africa in what is now Zimbabwe. This empire, now known as the Great Zimbabwe Empire, traded with merchants from Arabia, India, Southeast Asia, and China, exchanging the products of its mines and foundries for silk, fine porcelain, and exotic jewelry. The Great Zimbabwe Empire collapsed around 1500 for reasons not yet understood (see Figure 7.11B).

Complex and varied social and economic systems existed in many parts of Africa well before the modern era. Several influential centers made up of dozens of linked communities developed in the forest and the savanna of the western Sahel. There, powerful kingdoms and empires rose and fell, such as Djenné; that of Ghana (700–1000 c.e.), centered in what is now Mauritania and southwestern Mali; and the Mali Empire (1250–1600 c.e.), centered a bit to the east on the Niger River in what became the famous Muslim trading and religious center of Tombouctou (Timbuktu), originally founded about 1100 c.e. by Tuareg nomads as a seasonal camp (see Figure 7.11C). Some rulers periodically sent large trade caravans carrying gold and salt through Tombouctou on to Makkah (Mecca), where their opulence was a source of wonder.

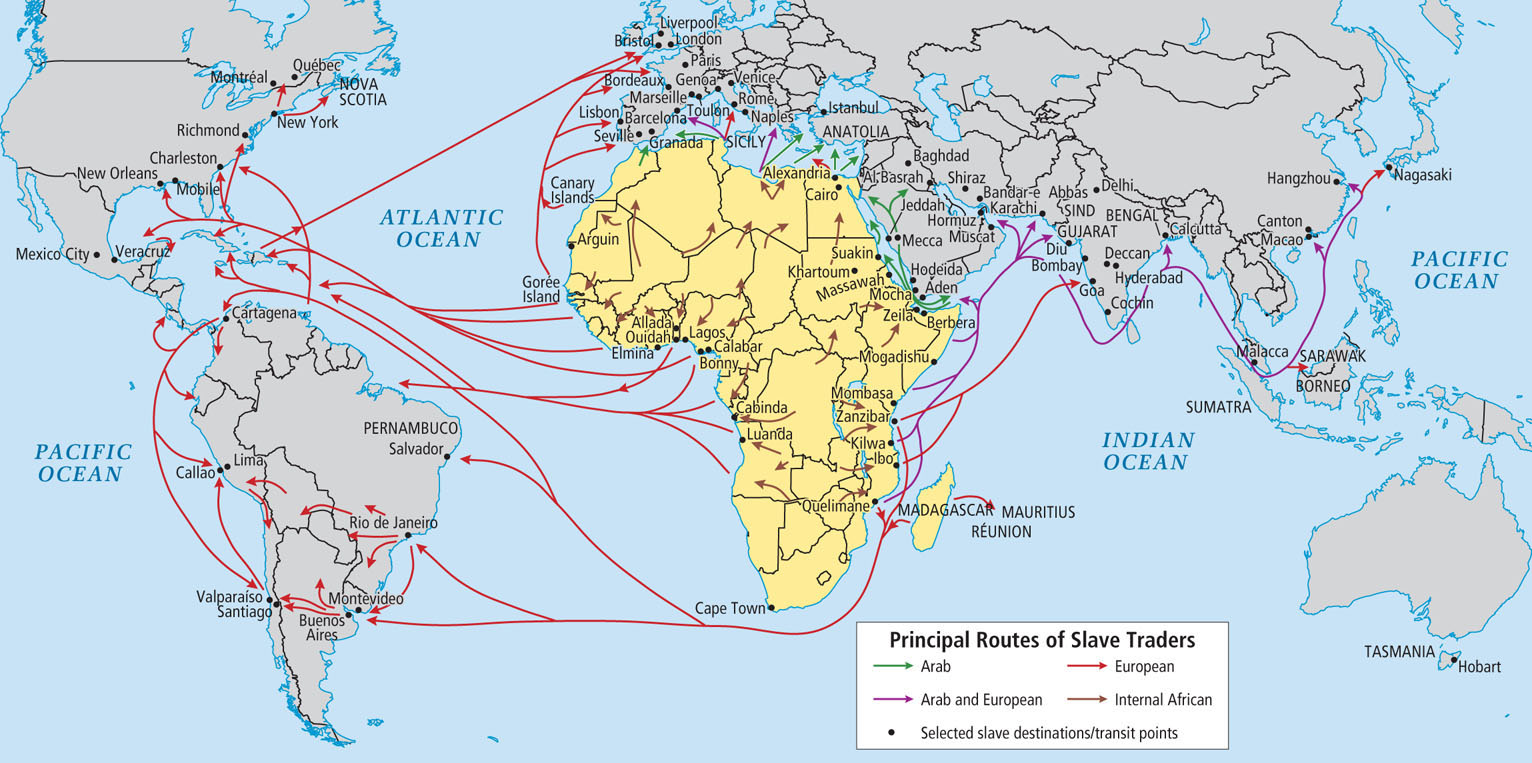

Africans also traded slaves. Long-standing customs of enslaving people captured during war fueled this trade. The treatment of slaves within Africa was sometimes brutal and sometimes relatively humane. Long before the beginning of Islam, a slave trade developed with Arab and Asian lands to the east. After the spread of Islam began around 700 c.e., the slave trade continued, and Muslim traders exported close to 9 million African slaves to parts of Southwest, South, and Southeast Asia (Figure 7.12). When slaves were traded to non-Africans, indigenous checks on brutality were abandoned. For example, to ensure sterility and to help promote passivity, Muslim traders often preferred to buy castrated male slaves.

The course of African history shifted dramatically in the mid-1400s, when Portuguese sailing ships began to appear off Africa’s west coast. The names given to stretches of this coast by the Portuguese and other early European maritime powers reflected their interest in Africa’s resources: the Gold Coast, the Ivory Coast, the Pepper Coast, and the Slave Coast.

By the 1530s, the Portuguese had organized a slave trade with the Americas. The trading of slaves by the Portuguese, and then by the British, Dutch, and French, was more widespread and brutal than any trade of African slaves that preceded it. African slaves became part of the elaborate production systems supplying the raw materials and money that fueled Europe’s Industrial Revolution.

To acquire slaves, the Europeans established forts on Africa’s west coast and paid nearby African kingdoms with weapons, trade goods, and money to make slave raids into the interior. Some slaves were taken from enemy kingdoms in battle. Many more were kidnapped from their homes and villages in the forests and savannas. Most slaves traded to Europeans were male because they brought the highest prices and the raiding kingdoms preferred to keep captured women for their reproductive capacities. Between 1600 and 1865, about 12 million captives were packed aboard cramped and filthy ships and sent to the Americas. One-quarter or more of them died at sea. Of those who arrived in the Americas, about 90 percent went to plantations in South America and the Caribbean. Between 6 and 10 percent were sent to North America (see Figure 7.12).

The European slave trade severely drained parts of Africa of human resources and set in motion a host of damaging social responses within Africa that are not completely understood even today (see Figure 7.11D). The trade enriched those African kingdoms that could successfully conquer their neighbors and impoverished or enslaved more peaceful or less powerful kingdoms. It also encouraged the slave-trading kingdoms to be dependent on European trade goods and technologies, especially guns.

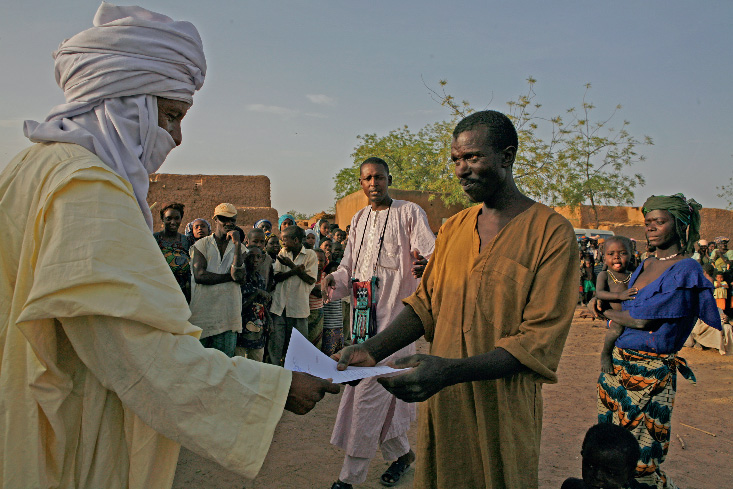

Slavery persists in modern Africa and is a growing problem that some argue exceeds the transatlantic slave trade of the past. Today, slavery is most common in the Sahel region, where several countries have made the practice officially illegal only in the past few years (Figure 7.13). People may become enslaved during war. They may be sold by their parents or relatives to pay off debts or forced into slavery when migrating to find a job in a city. Some are even enslaved by gangsters in Europe, where they become street vendors, domestic servants, or prostitutes. In Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria, forced child labor is used increasingly in commercial agriculture, such as cacao (chocolate) production. In Liberia, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, and Congo, young boys have been enslaved as miners and warriors. It is hard to know exactly how many Africans are currently enslaved, but estimates range from several million to more than 10 million.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What does this photo suggest about the social relationships of the man being freed from slavery in Niger?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

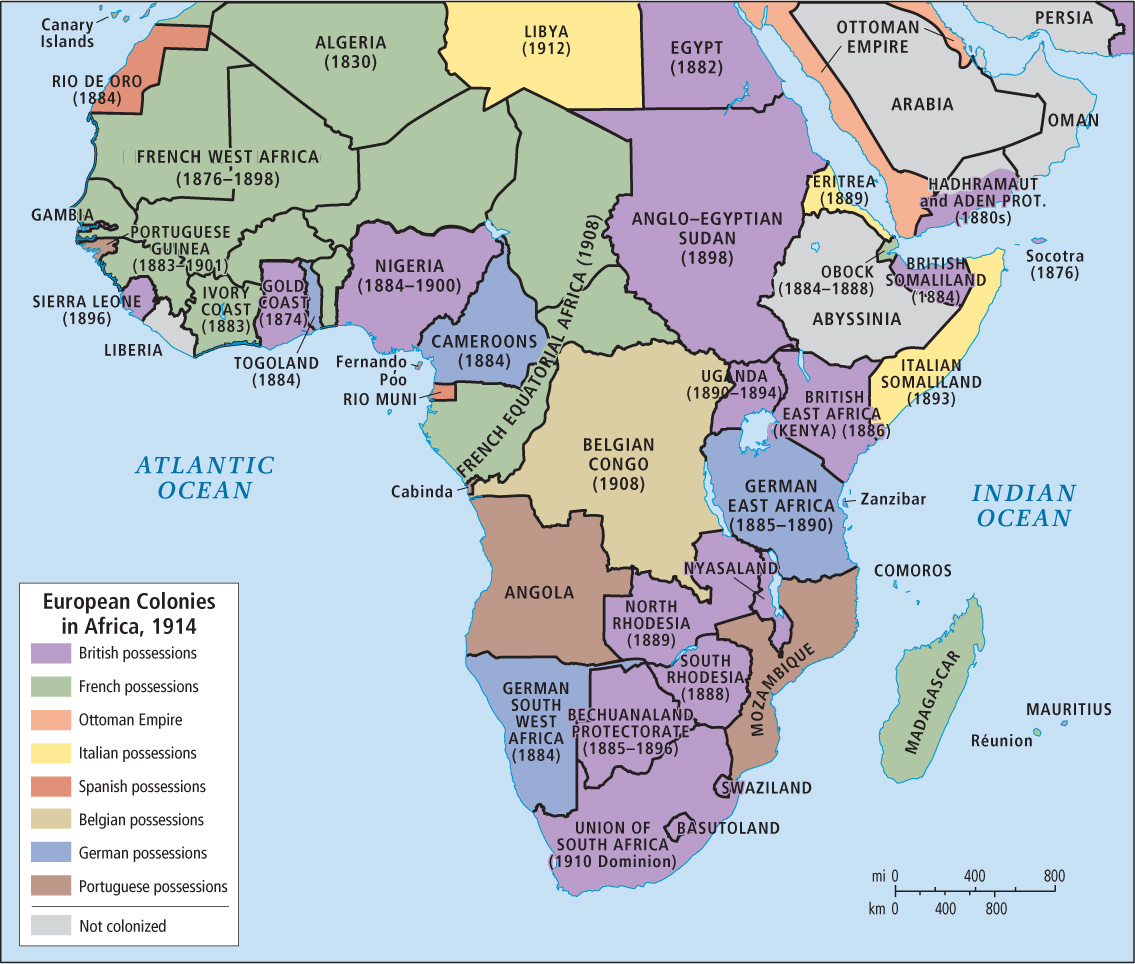

The Scramble to Colonize Africa

The European slave trade wound down by about the mid-nineteenth century, as Europeans found it more profitable to use African labor within Africa to extract raw materials for Europe’s growing industries.

European colonial powers competed avidly for territory and resources, and by World War I, only two areas in Africa were still independent (Figure 7.14): Liberia on the west coast (populated by former slaves from the United States) and Ethiopia (then called Abyssinia) in East Africa. Ethiopia managed to defeat early Italian attempts to colonize it. Otto von Bismarck, the German chancellor who convened the 1884 Berlin Conference at which the competing European powers formalized the partitioning of Africa, revealed the common arrogant European attitude when he declared, “My map of Africa lies in Europe.” With some notable exceptions, the boundaries of most African countries today derive from the colonial boundaries set up between 1840 and 1916 by European administrators and diplomats to suit their purposes (see Figure 7.11E). These territorial divisions lie at the root of many of Africa’s current problems.

In some cases, the boundaries were purposely drawn to divide tribal groups and thus weaken them. In other cases, groups who used a wide range of environments over the course of a year were forced into smaller, less diverse lands or forced to settle down entirely, thus losing their traditional livelihoods. As access to resources shrank, hostilities between competing groups developed. Colonial officials often encouraged these hostilities, purposely replacing strong leaders with leaders who could be manipulated. Food production, which was the mainstay of most African economies until the colonial period, was discouraged in favor of activities that would support European industries: cash-crop production (cotton, rubber, palm oil) and mineral and wood extraction. Eventually, many formerly prosperous Africans were hungry and poor.

One of the main objectives of European colonial administrations in Africa, in addition to extracting as many raw materials as possible, was to create markets in Africa for European manufactured goods. The case of South Africa provides insights into European expropriation of African lands and the subjugation of African peoples. In this case, these aims ultimately led to the infamous system of racial segregation known as apartheid (see below).

A Case Study: The Colonization of South Africa

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky peninsula that shelters a harbor on the southwestern coast of South Africa. Portuguese navigators seeking a sea route to Asia first rounded the Cape in 1488. The Portuguese remained in nominal control of the Cape until the 1650s, when the Dutch took possession with the intention of establishing settlements. Dutch farmers, called Boers, expanded into the interior, bringing with them herding and farming techniques that used large tracts of land and depended on the labor of enslaved Africans. The British were also interested in the wealth of South Africa, and in 1795, they seized control of areas around the Cape of Good Hope. When slavery was outlawed throughout the British Empire in 1834, large numbers of slave-owning Boers migrated to the northeast in order to keep their slaves. There, in what became known as the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, the Boers often came into violent conflict with African inhabitants.

In the 1860s, extremely rich deposits of diamonds and gold were unearthed in these areas, securing the Boers’ economic future. African men were forced to work in the diamond and gold mines under extreme hardship and unsafe conditions for minimal wages. They lived in unsanitary compounds that travelers of the time compared to large cages.

Britain, eager to claim the wealth of the mines, invaded the Orange Free State and the Transvaal in 1899, waging the Boer War. This brutal war gave the British control of the mines briefly, until resistance by Boer nationalists forced the British to grant independence to South Africa in 1910. This independence, however, applied to only a small minority of whites: the Boers (who have since been known as Afrikaners) and some British people who chose to remain. Not until 1994 would full political rights (voting, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, freedom to live where one chose) be extended to black South Africans—who made up more than 80 percent of the population—and to Asians and mixed race or “coloured” people (2 percent and 8 percent of the population, respectively).

apartheid a system of laws mandating racial segregation. South Africa was an apartheid state from 1948 until 1994

The African National Congress (ANC) was the first and most important organization that fought to end racial discrimination in South Africa. Formed in 1912 to work nonviolently for civil rights for all South Africans, the ANC grew into a movement with millions of supporters, most of them black but some of them white. Its members endured decades of brutal repression by the white minority. One of the most famous members to be imprisoned was Nelson Mandela, a prominent ANC leader, who was jailed for 27 years and finally released in 1990.

Violence increased throughout South Africa until the late 1980s, when it threatened to engulf the country in civil war. The difficulties of maintaining order, combined with international political and economic pressure, forced the white-dominated South African government to initiate reforms that would end apartheid. A key reform was the dismantling of the homelands. Finally, in 1994, the first national elections in which black South Africans could participate took place. Nelson Mandela, the long-jailed ANC leader, was elected the country’s president and proved to be an extraordinary leader. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. Today in South Africa, finding new leaders with the unselfish, clear-eyed vision Mandela had has proven difficult. The thorny process of dismantling systems of racial discrimination and corruption continues, with varying amounts of success.

Power and Politics in the Aftermath of Independence

The era of formal European colonialism in Africa was relatively short. In most places, it lasted for about 80 years, from roughly the 1880s to the 1960s. In 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African colonial state to become independent. The last sub-Saharan African country to gain independence was South Sudan in 2011, not from a European power, but from its neighbor Sudan, after more than 40 years of civil war.

Africa entered the twenty-first century with a complex mixture of enduring legacies from the past and looming challenges for the future. Although it has been liberated from colonial domination, most old colonial borders remain intact (compare the colonial borders in Figure 7.14 with the modern country borders in Figure 7.4). Often these borders exacerbate conflicts between incompatible groups by joining them into one resource-poor political entity; other borders divide potentially powerful ethnic groups, thus diminishing their influence, or cut off nomadic people from resources formerly used on a seasonal basis.

For many years and with few exceptions, governments continued to mimic the colonial bureaucratic structures and policies that distanced them from their citizens. Corruption and abuse of power by bureaucrats, politicians, and wealthy elites stifled individual initiative, civil society, and entrepreneurialism, creating instead frustration and suspicion. Too often, coups d’état were used to change governments. Democracy, where it existed, was often weakly connected only to voting and not to true participation in policy making at the community, regional, and national levels.

Other relics of the colonial era are the dependence of African economies on relatively expensive imported food and manufactured goods as well as the production of agricultural and mineral raw materials for which profit margins are low and prices on the global market highly unstable. Thus, many sub-Saharan African countries often compete against each other and remain economically entwined in trade relationships that rarely work to their advantage.

The wealthiest country in the region remains South Africa, where the economy has highly profitable manufacturing and service sectors as well as extractive sectors. However, South Africa is no longer assured of remaining the economic leader of the region. Too often, politicians are insensitive to the widespread poverty and hardship around them, content to live well themselves. This was demonstrated during the summer of 2010 when South Africa hosted the 2010 World Cup for soccer, the world’s largest sporting event and a first for this region, which up to that point had never hosted an Olympics or an event of similar scale. The preparations involved demolishing the homes of tens of thousands of poor urban residents who were relocated to make way for the elegant new stadiums (see Figure 7.11F). More recently, in an August 2012 crackdown reminiscent of those under apartheid, police shot dead 34 miners during a strike at a platinum mine in Marikana in Northwest Province. Other strikes followed.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved from earlier hominoids in eastern Africa about 250,000 years ago. By about 90,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had reached the eastern Mediterranean. They joined and eventually replaced other hominid species from Africa that had migrated throughout Eurasia starting 1.8 million years ago.

Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved from earlier hominoids in eastern Africa about 250,000 years ago. By about 90,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had reached the eastern Mediterranean. They joined and eventually replaced other hominid species from Africa that had migrated throughout Eurasia starting 1.8 million years ago. Agriculture, industry, and international trade have an early history in Africa; agriculture began as early as 7000 years ago in northeast sub-Sahara; iron smelting 3400 years ago; and trade extended across the Indian Ocean to Asia long before Europeans came to Africa.

Agriculture, industry, and international trade have an early history in Africa; agriculture began as early as 7000 years ago in northeast sub-Sahara; iron smelting 3400 years ago; and trade extended across the Indian Ocean to Asia long before Europeans came to Africa. Slavery was practiced in Africa within several powerful kingdoms, and then pre-Islam Arab traders extended the custom around the Mediterranean and to Asia. Muslims continued the practice. The European slave trade to the Americas severely drained the African interior of human resources and set in motion a host of damaging social responses within Africa. Slavery persists in parts of modern Africa.

Slavery was practiced in Africa within several powerful kingdoms, and then pre-Islam Arab traders extended the custom around the Mediterranean and to Asia. Muslims continued the practice. The European slave trade to the Americas severely drained the African interior of human resources and set in motion a host of damaging social responses within Africa. Slavery persists in parts of modern Africa. The main objectives of European colonial administrations in Africa were to extract as many raw materials as possible; to create markets in Africa for European manufactured goods and food exports; and to divide and conquer by splitting powerful ethnic groups or by placing groups hostile to one another under the same jurisdiction, governed by complicit indigenous leaders.

The main objectives of European colonial administrations in Africa were to extract as many raw materials as possible; to create markets in Africa for European manufactured goods and food exports; and to divide and conquer by splitting powerful ethnic groups or by placing groups hostile to one another under the same jurisdiction, governed by complicit indigenous leaders. During the era of European colonialism, human talent and natural resources flowed out of Africa on a massive scale. Even after the countries of the region became politically independent, wealth continued to flow out of Africa because of fraud and unfavorable terms of trade.

During the era of European colonialism, human talent and natural resources flowed out of Africa on a massive scale. Even after the countries of the region became politically independent, wealth continued to flow out of Africa because of fraud and unfavorable terms of trade. Into the twenty-first century, governments have continued to mimic colonial policies, including corruption, in ways that have kept sub-Saharan African countries economically dependent. This has stifled individual initiative, civil society, and entrepreneurialism. Democracy, where it exists, is often weak.

Into the twenty-first century, governments have continued to mimic colonial policies, including corruption, in ways that have kept sub-Saharan African countries economically dependent. This has stifled individual initiative, civil society, and entrepreneurialism. Democracy, where it exists, is often weak. South Africa trod a rocky road through colonial oppression and apartheid to its present relatively precarious position as the wealthiest country in sub-Saharan Africa.

South Africa trod a rocky road through colonial oppression and apartheid to its present relatively precarious position as the wealthiest country in sub-Saharan Africa.