Economic and Political Issues

Sub-Saharan Africa emerged from the exploitation and dependence of the colonial era just in time to get sucked into the vortex of globalization, where small or weak countries are often left with little control over their fates.

Commodity-Based Economic Development and Globalization in Africa

Geographic Insight 2

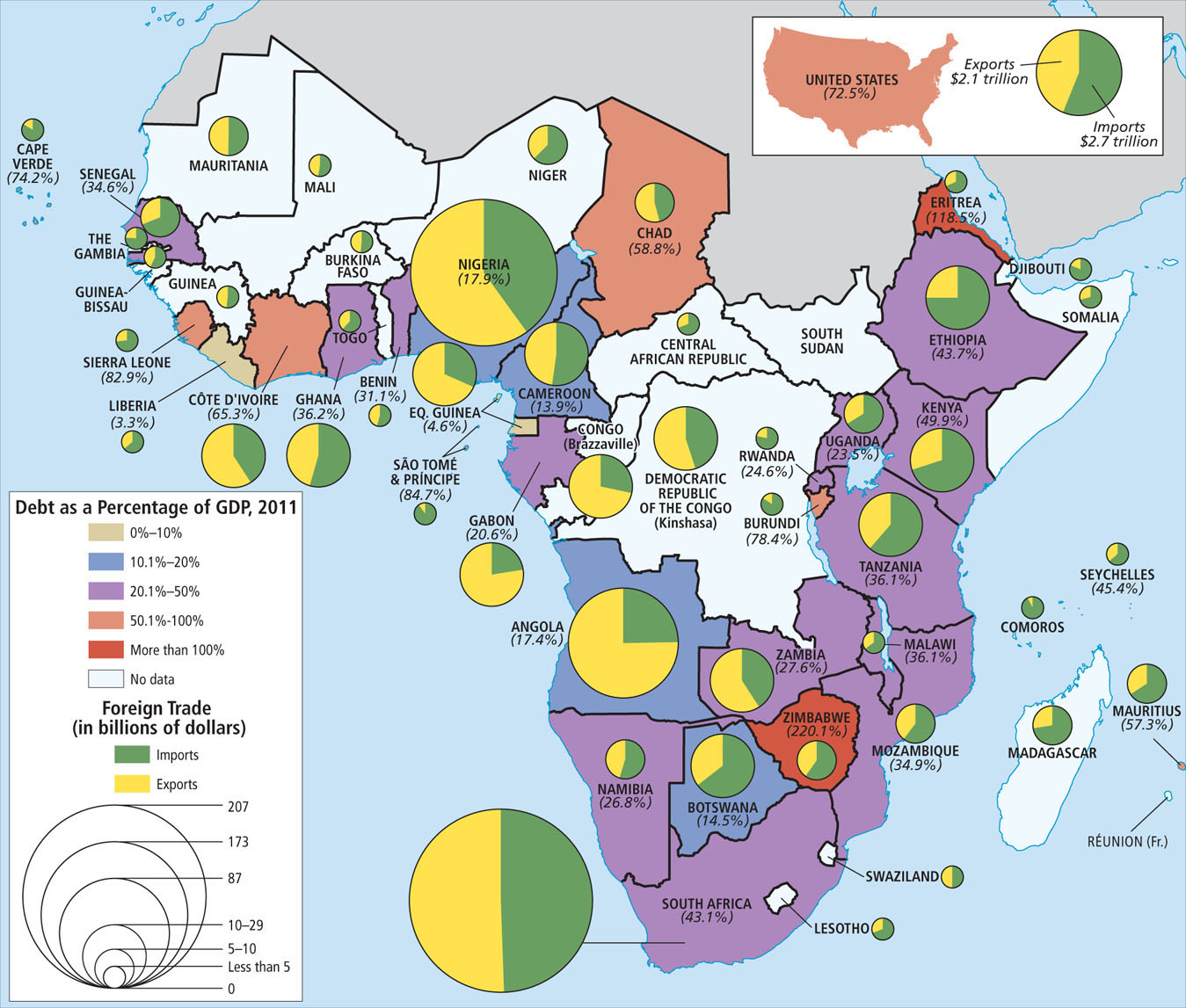

Globalization and Development: During the era of colonialism, Europeans set up the pattern that continues to this day of basing the economies of sub-Saharan Africa on the export of raw materials. This leaves countries vulnerable in the global economy, where prices for raw materials can vary widely year to year. While a few countries are diversifying and industrializing, most still sell raw materials and all rely on expensive imports of food, consumer products, and construction and transportation equipment.

commodities raw materials that are traded, often to other countries, for processing or manufacturing into more valuable goods

Commodity prices are also subject to wide fluctuations that create economic instability. This is because commodities are of more or less uniform quality and are traded as such on a global basis. For example, on the major commodities exchanges, a pound of copper may sell for U.S.$3 to $5, regardless of whether it is mined in South Africa, Chile, or Papua New Guinea. Because of the global scale of commodity trading, a change anywhere in the world that influences the supply or demand for a particular commodity can cause immediate instability in the pricing of that commodity. For instance, an earthquake in Chile could damage a major copper mine, restricting the supply of copper and sending up the price on world markets. In response, governments that make money from sales of raw copper may overestimate their future revenues and commit to expensive infrastructure projects. But the demand for copper can be decreased for many reasons; for example, innovations in the construction industry can reduce the use of copper in wiring and plumbing—resulting in sudden drops in the price of copper on world markets. Governments that depend on revenues from copper may suddenly need to halt infrastructure projects and cut essential services, such as electricity, road maintenance, or health care.

Since 2000 there has been a noticeable shift in many African countries, away from reliance on just one or two commodities. Nearly all have diversified to some extent, a trend that is discussed in the section “The Present Era of Diverse Globalization”.

Successive Eras of Globalization

commodity dependence economic dependence on exports of raw materials

Most early European colonial administrations in Africa (Britain, France, Germany, Belgium) evolved directly out of private resource-extracting corporations, such as the German East Africa Company. The welfare of Africans and their future development was a low priority for most colonial administrators. Education and health care for Africans were generally neglected by colonial governments, which were guided by mercantilism (see Chapter 3)—the idea that colonies existed to benefit their colonizers. Laborers and farmers were paid poorly and the colonial governments strongly discouraged any other economic activities that might compete with Europe. Thus, African economies were hindered from making a transition to the more profitable manufacturing-based industries that were transforming Europe and North America.

For years, commodity dependence, widespread poverty, and the lack of internal markets for local products and services characterized all sub-Saharan African economies, with the partial exception of South Africa.

South Africa is the only sub-Saharan African country with a manufacturing base. Early on, profits from its commodity exports (mainly minerals) were reinvested in the manufacturing of mining and railway equipment. In the late twentieth century, South Africa developed a service sector, with particular strengths in finance and communications, that in part support the mining and manufacturing industries. With only 6 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s population, South Africa today produces 30 percent of the region’s economic output.

dual economy an economy in which the population is divided by economic disparities into two groups, one prosperous and the other near or below the poverty level

The Era of Structural Adjustment

By the 1980s, most African countries remained poor and dependent on their volatile and relatively low-value commodity exports. Attempts at investing in manufacturing industries failed (discussed below), and governments struggled to make payments on the large loans taken out for these projects. Infrastructure (roads, water, and utilities) was either not built or not maintained. A breaking point came in the early 1980s when an economic crisis swept through the region and much of the rest of the developing world, leaving most countries unable to repay their debts at all. In response, the IMF and the World Bank designed structural adjustment programs (SAPs; see Chapter 3) to enforce repayment of the loans. SAPs did have some useful results. They tightened bookkeeping procedures and thereby curtailed corruption and waste in bureaucracies. They closed some corrupt state-owned industrial and service monopolies, opened some sectors of the economy to medium- and small-scale business entrepreneurs, and made tax collection more efficient. But overall, SAPs had many unintended consequences, and surprisingly, they failed at their primary objective—reducing debt (Figure 7.16).

To facilitate loan repayment, SAPs required governments to sell off inefficient government-owned enterprises, often at bargain-basement prices. Also, government jobs in social services, education, health, and agricultural programs were slashed so that tax revenues could be devoted to loan repayment. If countries refused to implement SAP requirements, the international banks cut off any future lending for economic development.

As unemployment rose, so did political instability. Deteriorating infrastructure reduced the quality of remaining social services, transportation, and financial services, all of which scared away potential investors. SAPs also reduced food security because agricultural resources were shifted toward the production of cash crops for export. Between 1961 and 2009, per capita food production in sub-Saharan Africa actually decreased by 14 percent, making it the only region on earth where people were eating less well than in the past (see Figure 1.14).

Informal Economies

Africa’s informal economies provided some relief from the hardships created by SAPs. Informal economies in Africa are ancient and wide-ranging, providing employment and useful services and products. People may grow and sell garden produce, prepare food, vend a wide array of products on the street, sell time cards (or credits) for mobile phones, make craft items and utensils, or do child and elder care. Others in the informal economy, however, earn a living doing less socially redeeming things such as sex work, distilling liquor, or smuggling scarce or illegal items including drugs, weapons, endangered animals, bushmeat, and ivory. Because most activities take place “under the radar,” informal jobs may involve criminal acts, wildly unsafe procedures, and hazardous substances.

In most African cities, the role of the informal economy has grown from one-third of all employment to more than two-thirds. Such jobs are a godsend to the poor, but they create problems for governments because the informal economy typically goes untaxed, so less money is available to pay for government services or to repay debts. Moreover, as the informal sector grows, profits have declined as more people compete to sell goods and services to those with little disposable income. And although women typically dominate informal economies, when large numbers of men lose their jobs in factories or the civil service, they may crowd into the streets and bazaars as vendors, displacing the women and young people.

In response to the now widely recognized failures of SAPs, and the overemphasis on the power of markets to guide development, the IMF and the World Bank in 2000 replaced SAPs with Poverty Reduction Strategy Programs, or PRSPs, and Sustainable Structural Transformation (SST) strategies. These policies are similar to SAPs in that they push market-based solutions intended to reduce the role of government in the economy, but they differ in several ways. They focus on reducing poverty and diversifying economies into manufacturing, rather than on just “development” and debt repayment per se, and are generally promoting more democratic reforms. They also include the possibility that a country may have all or most of its debt “forgiven” (paid off by the IMF, the World Bank, or the African Development Bank) if the country follows the PRSP rules. Forty sub-Saharan countries had qualified for and been approved to receive debt relief by July 2010.

The Present Era of Diverse Globalization

The current wave of globalization promises a different role for Africa, resulting in new sources of investment that are bringing jobs and infrastructure. As discussed at the beginning of the chapter, one significant trend is that young African professionals at home and abroad are supporting development in a multitude of ways. Another trend is foreign direct investment (FDI) at the corporate level. While Europe and the United States are still the largest sources of investment in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia’s influence on African economies is increasing significantly, but there are potential problems involved in Asia’s role.

In recent years, China and India have begun to view sub-Saharan Africa as a new frontier for their large and growing economies. These two countries now exert a powerful influence on the region through their demand for Africa’s export commodities, direct investment in agribusiness, mining and industry, and the sale of their manufactured goods. Of the two, China’s influence is the greater.

Together, China and India consume about 15 percent of Africa’s exports, but their share is growing twice as fast as is that of any of Africa’s other trading partners. However, the increasing Chinese and Indian demand for resources is a double-edged sword; it is not clear if Asian investments will ultimately prove beneficial or hurtful to sub-Saharan African economies. The improved infrastructure (roads, ports, utilities, and technology) could ultimately facilitate intra-African trade, linking countries that have never before been able to trade. China’s and India’s investment in African agriculture, undertaken to meet rising demands for better food in China and India, could result in more efficient production overall through technology transfer and thus higher earnings for Africa and greater food supplies for African internal urban markets. Overall, African food security could increase.

It is important, however, to keep an eye on the extent to which Asian investments in Africa actually benefit Africans rather than simply replicating the injustices of colonialism. For example, Chinese investments in mining and infrastructure development could have boosted local African economies by providing construction jobs for African laborers and professional design and management experience for mid-level educated Africans, but this benefit never materialized because African governments agreed to China’s demand that all work be done by Chinese companies using Chinese workers (Figure 7.17). Most controversial has been the willingness of Chinese companies to deal with brutal and corrupt local leaders, such as Liberia’s now convicted and imprisoned Charles Taylor (diamonds and timber extraction) or Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe (mining), who bartered away their country’s resources at bargain prices and used the profits to enrich themselves and to wage war against their own citizens.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why might China be particularly interested in investment in Africa's transportation infrastructure?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

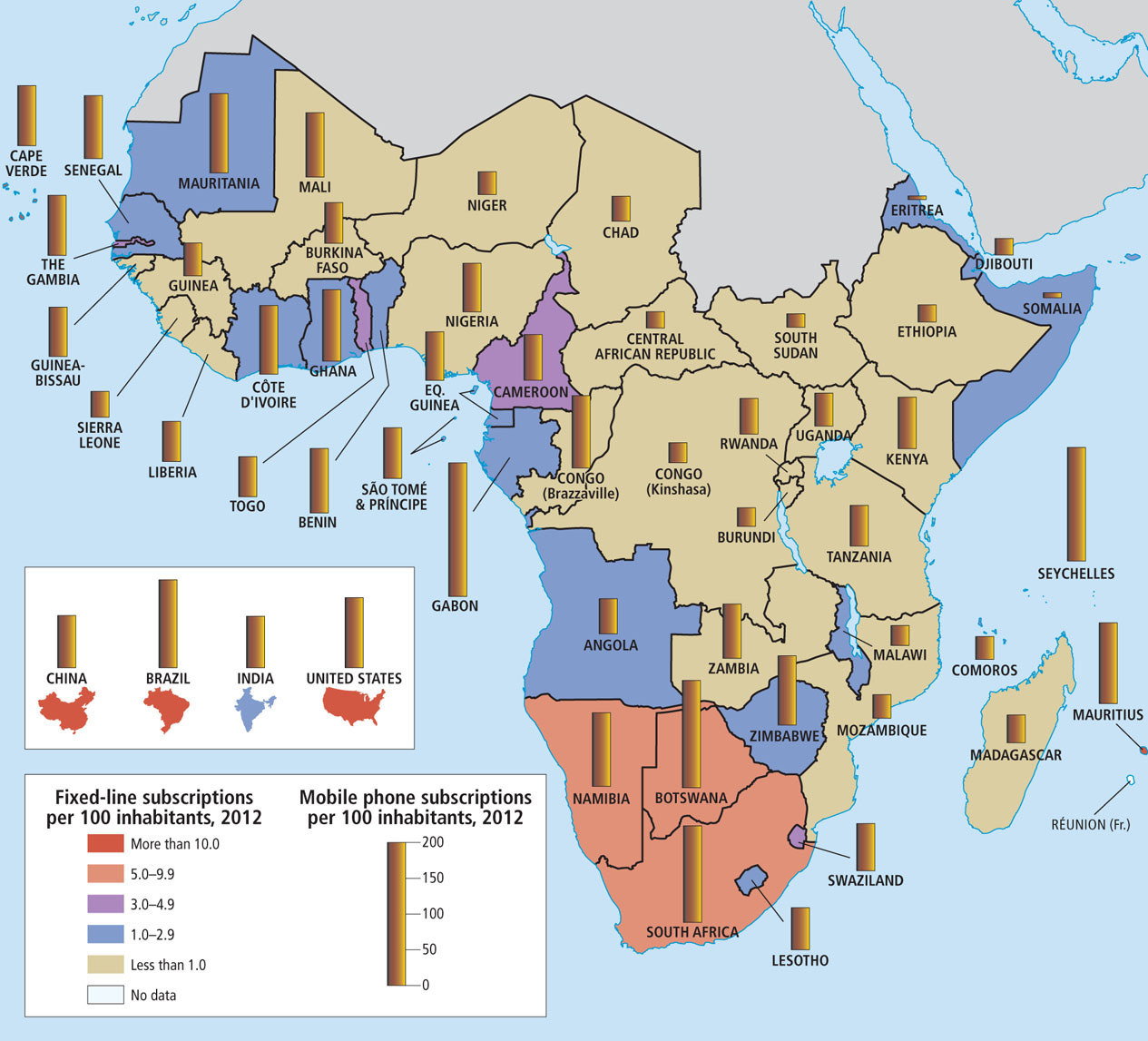

Another example of private investment is from the Kuwaitibased mobile company, Zain, which launched a borderless network that now covers 13 countries: Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, Uganda, Congo (Kinsasha), Congo (Brazzaville), Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Madagascar, and Zambia. Zain’s customers can make calls across the network at local rates without incurring surcharges; recently, the company added Internet access, SMS, international roaming, and portal applications to the local rate.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Africans Investing in Africa

The role of African professionals in globalization is growing. As was noted in the opening vignette, perhaps the most dramatic sign of change for African economies is that educated Africans familiar with high tech and the globalized world are staying home and starting businesses that link their countries to the technological advantages that have spurred development elsewhere. Their incomes, along with remittances (money sent to family members from Africans working and living abroad, primarily in Europe and North America), buy mobile phones, start small businesses, fund education for children, build houses, and help the needy. Remittances are a more stable source of investment than foreign direct investment, in that they tend to come regularly from committed donors who will continue their support for years. They are also much more likely to reach poorer communities. But payments can stop if remitters lose their jobs in America or Europe.

Young, educated adults are profoundly changing the trajectory of Africa’s development. They have been largely responsible for the rapid spread of mobile phones and have developed a wide array of new and important uses of cell phone technology. Figure 7.18 is a map of mobile phone subscriptions by country as of 2011. Between 1998 and 2010, mobile phone subscribers in sub-Saharan Africa increased by more than 100 times, from about 4 million to about 450 million. Google estimates that by 2016 there will be a billion mobile phones in sub-Saharan Africa, one for every person. An African innovation has been to make service available to the very poor by selling prepayment credits in very small units. In fact, many people now make a living selling these small credits. Private investment is improving connectivity by financing undersea cable connections.

The expansion of communication technology has inspired a wide range of innovations, such as imaginative ways to lay out networks in difficult terrain and ways to charge mobile phones in remote villages where there is no electricity, as the Malawian William Kamkwamba figured out how to do (for more on William Kamkwamba’s story, see the vignette).

160. SOMALILAND EXPATRIATES RETURN HOME TO HELP NATIVE LAND DEVELOP

160. SOMALILAND EXPATRIATES RETURN HOME TO HELP NATIVE LAND DEVELOP

Regional and Local Economic Development

As they create alternatives to past development strategies, many African governments have been focusing on regional economic integration similar to that of the European Union. Hoping to unleash pent-up talent and consumer demand for African-made products, local agencies and public and private donors are pursuing grassroots development designed to foster very basic innovation at the local level that can then be marketed across the region.

The Potential of Regional Integration

According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), less than 20 percent of the total trade of sub-Saharan Africa in 2011 was conducted between African countries. This is true partly because so many countries produce the same raw materials for export. And everywhere except South Africa, industrial capacity is so low that the raw materials cannot be absorbed within the continent, so African countries compete with each other and all other global producers to sell to the main customers, which currently are in Europe, North America, and industrialized Asia. This failure to trade with each other can be traced to divisive colonial policies, lack of transportation and communication grids, and arcane bureaucratic regulations.

African Regional Integration

Over the last decades, regional trading blocs have been formed to encourage neighboring countries to trade with each other and cooperate in the production of manufactured (value-added) exports. The trade blocs are somewhat fluid; they form and then reorganize, as is depicted in Figure 7.19, a list and simplified map of the evolving African Regional Economic Communities (RECS). By combining the markets of several countries (as do NAFTA and the EU), regional trade blocs can create a market size sufficient to foster industrialization and entrepreneurialism. Africa’s many different regional trade blocs share several goals: reducing tariffs between members, forming common currencies, reestablishing peace in war-torn areas, cooperating to upgrade transportation and communication infrastructure, and building regional industrial capacity.

These goals could be helped by the creation of value chains; the value chain approach analyzes all parts of a production chain of a final product—a tractor, a refrigerator, or chocolates—and the relationships among the parts. The goal is to facilitate production and marketing efficiencies and enable the flow of information, innovation, resources, and the products and profits so that the producers of raw materials are included and can live decent lives. Such value chains, which encourage efficient transport and specialization in products and labor skills, are second only to the fuel trade as the fastest-growing portions of global trade.

Building a full-scale, continent-wide economic union along the lines of the European Union is a long-term goal. According to studies by the WTO, if sub-Saharan countries could increase trade with each other by just 1 percent, the region would show a total added income of $200 billion per year—a substantial internal contribution to poverty alleviation.

Local Development

grassroots economic development economic development projects designed to help individuals and their families achieve sustainable livelihoods

self-reliant development small-scale development in rural areas that is focused on developing local skills, creating local jobs, producing products or services for local consumption, and maintaining local control so that participants retain a sense of ownership over the process

Transportation Needs

The issue of improving rural transportation illustrates how a focus on local African needs can generate unique solutions. When non-Africans learn that transportation facilities in Africa are in need of development, they usually imagine building and repairing roads for cars and trucks. But a recent study that analyzed village transportation on a local level found that 87 percent of the goods moved are carried via narrow footpaths on the heads of women! Women “head up” (their term) firewood from the forests, crops from the fields, and water from wells. An average adult woman spends about 1.5 hours each day moving the equivalent of 44 pounds (20 kilograms) more than 1.25 miles (2 kilometers).

Unfortunately, the often-treacherous footpaths trod by Africa’s load-bearing women have been virtually ignored by African governments and international development agencies, which tend to focus solely on roads for motorized vehicles (also badly needed). Grassroots-oriented nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are now making much less expensive but equally necessary improvements to Africa’s footpaths. Some women have been provided with bicycles, donkeys, and even motorcycles that can travel on the footpaths. This saves time and energy for women who can direct more of their efforts to becoming educated and generating income.

Energy Needs

Africa exports oil, but its own energy needs, which are currently unmet even at the most basic level of home electricity, can also be addressed by local solutions, as the following vignette illustrates.

VIGNETTE

In Malawi, 14-year-old William Kamkwamba was forced to drop out of school when a famine struck his country in 2001 and his family could no longer afford the $80 school fee. Depressed at the prospect of having no future, he went to a local library when he could. There he found a book in English called Using Energy that described an electricity-generating windmill. With an old bicycle frame, tractor fan blades, PVC pipes, and scraps of wood, he built a windmill that generated enough power (stored in a car battery) to light his home, run a radio, and charge neighborhood cell phones. More elaborate energy projects followed.

Now known as “the boy who harnessed the wind,” in 2009 William appeared on Jon Stewart’s Daily Show in the United States to explain how he plans to start his own windmill company and other ventures that will bring power to remote places across Africa. He graduated from the first pan-African prep school in South Africa and now attends Dartmouth College in the United States. William’s web page is http://www.williamkamkwamba.com.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 2Globalization and Development Continuing reliance on the export of raw materials leaves countries vulnerable, especially because in the globalized economy, where all producers are in competition, prices can vary widely year to year. Most countries still primarily sell raw materials and must rely on expensive imports for daily necessities and manufactured equipment essential for further development.

Geographic Insight 2Globalization and Development Continuing reliance on the export of raw materials leaves countries vulnerable, especially because in the globalized economy, where all producers are in competition, prices can vary widely year to year. Most countries still primarily sell raw materials and must rely on expensive imports for daily necessities and manufactured equipment essential for further development. Prospective investors in sub-Saharan Africa have been discouraged by problems that structural adjustment programs (SAPs) either ignored or worsened. Recently, though, Africa has become a new frontier for Asia’s large and growing economies, especially those of China and India, that both buy and sell in sub-Saharan Africa.

Prospective investors in sub-Saharan Africa have been discouraged by problems that structural adjustment programs (SAPs) either ignored or worsened. Recently, though, Africa has become a new frontier for Asia’s large and growing economies, especially those of China and India, that both buy and sell in sub-Saharan Africa. A major and enduring source of investment funds in Africa is coming from members of the African diaspora, who send regular remittances to friends and family.

A major and enduring source of investment funds in Africa is coming from members of the African diaspora, who send regular remittances to friends and family. Many African governments are focusing on regional economic integration along the lines of the European Union. Grassroots economic development is also being pursued.

Many African governments are focusing on regional economic integration along the lines of the European Union. Grassroots economic development is also being pursued. Africa’s informal economies have provided some relief from the hardships created by SAPs. These economies are ancient, wide ranging, and agile; they provide employment and useful services and products.

Africa’s informal economies have provided some relief from the hardships created by SAPs. These economies are ancient, wide ranging, and agile; they provide employment and useful services and products.

Power and Politics

Geographic Insight 3

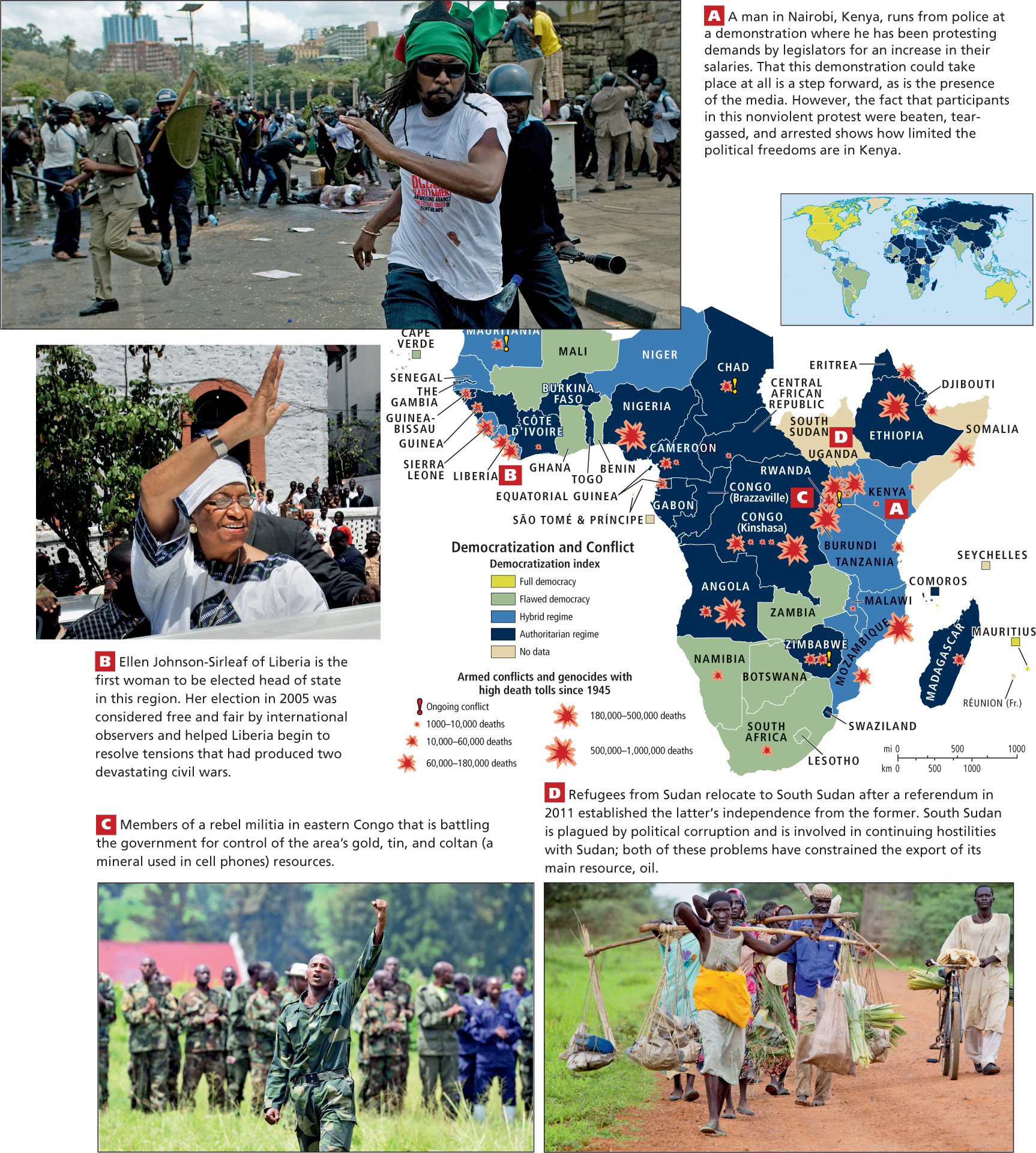

Power and Politics: Countries in the region are shifting from authoritarianism to elections and other democratic institutions, but the power structures in the region are resistant to democratization. While free and fair elections have brought about dramatic changes, distrusted elections have often been followed by surges of violence.

After years of rule by corrupt elites and the military, signs of a shift toward democracy and free elections are now visible across Africa. Yet progress is often blocked by conflict, and even when democratic reforms are enacted and free elections established, violence often accompanies these elections.

Ethnic Rivalry

divide and rule the deliberate intensification of divisions and conflicts by potential rulers; in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, by European colonial powers

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about democratization and conflict in sub-Saharan Africa, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

In what ways does this picture show both the strengths and limits of political freedoms in Kenya?

In what ways does this picture show both the strengths and limits of political freedoms in Kenya?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why might it be significant that Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf was elected as Liberia's president without the help of quotas that reserve certain elected positions for women?

Why might it be significant that Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf was elected as Liberia's president without the help of quotas that reserve certain elected positions for women?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What does this photo suggest about the strength of this rebel militia and the militia's methods of acquiring uniforms and arms?

What does this photo suggest about the strength of this rebel militia and the militia's methods of acquiring uniforms and arms?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What does this photo convey about the general well-being of the people depicted?

What does this photo convey about the general well-being of the people depicted?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

A Case Study: Conflict in Nigeria

Nigeria was and remains in part a creation of British divide-and-rule imperialism. Many disparate groups—speaking 395 indigenous languages—have been joined into one unusually diverse country.

The British reinforced a north-south dichotomy that mirrored the physical north (dry)-south (wet) patterns. Among the Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups in the north, the British ruled via local Muslim leaders who did not encourage public education. In the south, the Yoruba and Igbo ethnic groups, who were primarily a combination of animist and Christian, were ruled more directly by the British, who encouraged attendance at Christian missionary schools, open to the public. At independence, the south had more than 10 times as many primary and secondary school students as the north. It was more prosperous, and southerners also held most government civil service positions. Yet the northern Hausa dominated the top political posts, in part because of their long association with British colonial administrators. Over the years, bitter and often violent disputes erupted between the southern Yoruba-Igbo and northern Hausa-Fulani regarding the distribution of increasingly scarce clean water, development funds, jobs, and oil revenues, and the severe environmental damage done by oil extraction.  178. NEW NIGERIAN PRESIDENT INHERITS TURBULENT NIGER DELTA

178. NEW NIGERIAN PRESIDENT INHERITS TURBULENT NIGER DELTA

The politics of oil have complicated the troubles in Nigeria. Nigeria’s oil is located on lands occupied by the Ogoni people, which lie in the south along the edges of the Niger River delta (see Figure 7.1D). The Ogani are a group of about 300,000 who are distinct from other ethnicities in Nigeria. Virtually none of the profits from oil production and export, and very little of the oil itself, goes to Ogoniland. While receiving few benefits from oil extraction, Ogoniland has suffered gravely from the resulting pollution (see the photo in Figure 1.4). Oil pipelines crisscross Ogoniland, and spills and blowouts are frequent; between 1985 and 2009 there were hundreds of spills, many larger than that of the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska. Natural gas, a by-product of oil drilling, is burned off, even though it could be used to generate electricity—something many Ogoni lack. Royal Dutch Shell, a multinational oil company that is very active in the Niger River delta, acknowledges that while it has historically netted $200 million in profit yearly from Nigeria, in 40 years, it has paid a total of just $2 million to the Ogoni community.

Geographic strategies have been used to reduce tensions in Nigeria. One approach has been to create more political states (Nigeria now has 30) and thereby reallocate power to smaller local units with fewer ethnic and religious divisions. However, when large, wealthy states were subdivided, reputedly to spread oil profits more evenly, the actual effect of the subdivision was to mute the voice and power of the public.

The Role of Geopolitics

Cold War geopolitics between the United States and the former Soviet Union deepened and prolonged African conflicts that grew out of divide-and-rule policies. After independence, some sub-Saharan African governments turned to socialist models of economic development, often receiving economic and military aid from the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Other governments became allies of the United States, receiving equally generous aid (see Figure 5.13). Both the United States and the USSR tried to undermine each other’s African allies by arming and financing rebel groups.

In the 1970s and 1980s, southern sub-Saharan Africa became a major area of East-West tension. The United States aided South Africa’s apartheid government in military interventions against Soviet-allied governments in Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique. Another area of Cold War tension was the Horn of Africa, where Ethiopia and Somalia fought intermittently throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. At different times, the Soviets and Americans funded one side or the other. The failure by both sides of the Cold War to anchor the aid they dispensed to any requirements that it be used for sustainable development became a major stimulant for militarization and corruption. Once this source of cash was removed at the end of the Cold War, corrupt officials turned to selling off natural resources and commodities.

Al Qaeda in Mali

In early 2012, Islamist geopolitics came to the north of Mali in the Sahara. The crisis began when the nomadic Tuareg ethnic group, accustomed for hundreds of years to using the whole of the Sahara without attention to country borders, increased their long-term efforts to have their right to move freely recognized. Mali’s weak central government, located far to the south in Bamako, the capital, responded so ineptly that a faction of Tuareg rebel forces, buttressed by arms and fighting experience as mercenaries for Colonel Qaddafi in Libya (deposed in October 2011), seized the northern Mali town of Kidal and the legendary Muslim trading city of Tombouctou. Meanwhile, Al Qaeda members and other jihadists recruited across North Africa during the Arab Spring joined the Tuareg, but only temporarily. Calling themselves “Al Qaeda in Mali,” this group apparently intended to take northern Mali from the Tuareg (some of whom are Sufi Muslims, while others are largely secular) and set up a regime based on Islamic Law (shari’a). Tuareg and Malian resistance to this grew over time.

The failed government response to both the Tuareg and Al Qaeda in Mali so irritated the Malian regular army that they themselves staged a coup in Bamako in the spring of 2012. However, under severe criticism from the African Union and the regional trade organization Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS; see Figure 7.19), the Malian army eventually backed down. A new government for southern Mali was formed in August 2012, but Al Qaeda in Mali increased its hold on the north and feuded with the Tuareg over visions of what type of entity the new northern state would be. The disruption severely damaged Mali’s tourist economy, which had been based on seasonal tourism to the Niger River basin and ancient sites in Djenné and Tombouctou. Tens of thousands of northern Malians, many of them Sufi Muslims (a version of Islam that believes in a benevolent, peaceful deity), fled south to Mauritania and told of harsh treatment by the Islamists.

By January 2013, neighboring states in North and sub-Saharan Africa worried that Al Qaeda’s influence would destabilize the continent. On January 11, France, the former colonial power in Mali, took a controversial step when it began a bombing campaign and sent 2000 troops to assist the African Union in dislodging the militants. For further coverage of Islamist geopolitics and shifting alliances in the Sahara, see Chapter 6.

Conflict and the Problem of Refugees

genocide the deliberate destruction of an ethnic, racial, religious, or political group

With only 11 percent of the world’s population, this region contains about 19 percent of the world’s refugees, and if people displaced within their home countries are also counted, the region has about 28 percent of the world’s refugee population (see Figure 7.21D). Women and children constitute 75 percent of Africa’s refugees because many adult men who would be refugees are either combatants, jailed, or dead.

As difficult as life is for these refugees, the burden on the areas that host them is also severe. Even with help from international agencies, the host areas find their own development plans deferred by the arrival of so many distressed people, who must be fed, sheltered, and given health care. Large portions of economic aid to Africa have been diverted to deal with the emergency needs of refugees.

Successes and Failures of Democratization

In sub-Saharan Africa, efforts to establish democratic institutions have produced mixed results. The number of elections held in the region has increased dramatically. In 1970, only 11 states had held elections since independence. By 2006, 25 out of the then 44 sub-Saharan African states had held open, multiparty, secret ballot elections, with universal suffrage. While the implementation of democratic elections has increased (see Figure 7.21B), the inauguration of other aspects of democracy, such as public participation in policy formation at the local and national levels, has been irregular and uneven. Too often, public frustration with election outcomes or with particular policies has resulted in violent demonstrations (see Figure 7.21A) or rebellion (see Figure 7.21C). When people have input at the policy level, governments tend to be more responsive to the needs of their people.

At times, flawed elections have brought about massive violence. Kenya, after several peaceful election cycles, had an election in 2008 so corrupt that deadly protest riots broke out. More than 1000 people died, and 600,000 were displaced by mobs of enraged voters. By 2010, a new Kenyan constitution gave some hope that political freedoms would be better protected. In 2008 in Nigeria, local elections sparked similar violence, and in the Congo (Kinshasa) in 2006, the first elections held there in 46 years resulted in violence that left more than 1 million Congolese refugees within their own country. In the 2012 parliamentary elections, the will of the voting public became more evident when the ruling party lost more than 40 percent of its legislative seats to opposition parties.

Zimbabwe may represent the worst case of the failure of democratization. In the 1970s, Robert Mugabe became a hero to many for his successful guerilla campaign in what was then called Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The defeated white minority government had been allied with apartheid South Africa but was not formally recognized by any other country because of its extreme racist policies. Mugabe was elected president in 1980, following relatively free, multiparty elections. Over the years, however, his authoritarian policies impoverished and alienated more and more Zimbabweans and increased his personal wealth. In the 1990s, he implemented a highly controversial land-redistribution program that resulted in his supporters gaining control of the country’s best farmland, much of which had been in the hands of white Zimbabweans. This move decimated agricultural production and contributed to a chronic food shortage and a massive economic crisis. The resulting political violence created 3 to 4 million refugees who fled mostly to neighboring South Africa and Botswana. Mugabe held on to his office through the rigged elections of 2002 and 2008, but was then forced to share power in 2009 with opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, who became prime minister. After some of Tsvangarai’s policies were implemented, Zimbabwe began to have some modest economic growth. In 2012, though, Mugabe called for early elections and appeared to be financing his campaign with money from state-owned diamond mines.  159. ZIMBABWE’S ROBERT MUGABE—A PROFILE

159. ZIMBABWE’S ROBERT MUGABE—A PROFILE

In other places, however (most recently in South Sudan and Rwanda and some years ago in South Africa), elections have helped end civil wars and resettle refugees (see Figure 7.21D), as the possibility of becoming respected elected leaders induced former combatants to lay down their arms. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, public outrage against corrupt ruling elites resulted in elections that brought fortuitous changes of leadership (see Figure 7.21B).

Gender and Democratization

Geographic Insight 4

Gender, Power, and Politics: The education of African women and their economic and political empowerment are now recognized as essential to development. As girls’ education levels rise, population growth rates fall; as the number of female political leaders increases, so does their influence on policies designed to reduce poverty.

One major characteristic of the democratization process has been the increase in the number of women across Africa who are assuming positions of political influence. This chapter opened with the story of Juliana Rotich, a businesswoman in Kenya, but her road to success was built on policy changes pushed by a number of female Kenyan political figures over the last decade. In Nigeria, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the first female finance minister, now fights for the empowerment of women entrepreneurs as a director at the World Bank. In Liberia—the country devastated by the logging fraud, child-soldier recruitment, and general brutality of the dictator Charles Taylor (see the vignette on Silas Siakor)—President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf (also a former World Bank economist) began to work on democratic and environmental reforms immediately after she took office (see Figure 7.21B). In Rwanda, racked by genocide and mass rapes in the 1990s, women now make up 51 percent of the national legislature, the highest percentage in the world. And Rwandan women are also leaders at the local level, where they make up 40 percent of the mayors. In Mozambique, 39.2 percent of the parliament is female; in Burundi, 36 percent; and in South Africa, 42.7 percent. All together, there are 17 African countries where the percentage of women in national legislatures is above the world average of 17.7 percent (the U.S. figure is 16.8 percent).  170. WOMEN HAVE STRONG VOICE IN RWANDAN PARLIAMENT

170. WOMEN HAVE STRONG VOICE IN RWANDAN PARLIAMENT

There has been a sea change in attitudes toward women in politics. The policies that establish quotas for the number of female members of parliament are usually a reflection of a larger, post-conflict commitment to the empowerment of women and to involving women in all aspects of political and civil society. Sometimes the quotas are written into a country’s constitution, but it is important to note that many female leaders in Africa, including Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf and at least half of Rwanda’s female parliamentarians, were elected without the aid of quotas.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 3Power and Politics After years of rule by corrupt elites and the military, signs of a shift toward democracy and free elections are now visible across Africa. Even when democratic reforms are enacted and free elections established, violence still accompanies some elections.

Geographic Insight 3Power and Politics After years of rule by corrupt elites and the military, signs of a shift toward democracy and free elections are now visible across Africa. Even when democratic reforms are enacted and free elections established, violence still accompanies some elections. Africa’s democratic and economic progress has been held back by frequent civil wars that are in many ways the legacy of colonial-era divide-and-rule policies.

Africa’s democratic and economic progress has been held back by frequent civil wars that are in many ways the legacy of colonial-era divide-and-rule policies. Democratization is helping reduce the potential for civil conflict, and the countries with the fairest elections have had noticeably fewer violent conflicts.

Democratization is helping reduce the potential for civil conflict, and the countries with the fairest elections have had noticeably fewer violent conflicts. The trend toward democracy in sub-Saharan Africa tends to lead to governments that are more responsive to the needs of their people, but democratic reforms are not necessarily durable.

The trend toward democracy in sub-Saharan Africa tends to lead to governments that are more responsive to the needs of their people, but democratic reforms are not necessarily durable. Geographic Insight 4Gender, Power, and Politics One major characteristic of the democratization process has been the increase in the number of women across Africa who are coming into positions of power, both political and economic.

Geographic Insight 4Gender, Power, and Politics One major characteristic of the democratization process has been the increase in the number of women across Africa who are coming into positions of power, both political and economic.