Sociocultural Issues

To the casual observer, it may appear that a majority of sub-Saharan Africans live traditional lives in rural villages. It is true that with just 37 percent of its population in urban areas, Africa is the world’s most rural region. A closer look, however, reveals that migration and urbanization are occurring so rapidly that the impact on African life is monumental.

Population Patterns: Growth, Density, and the Demographic Transition

Geographic Insight 5

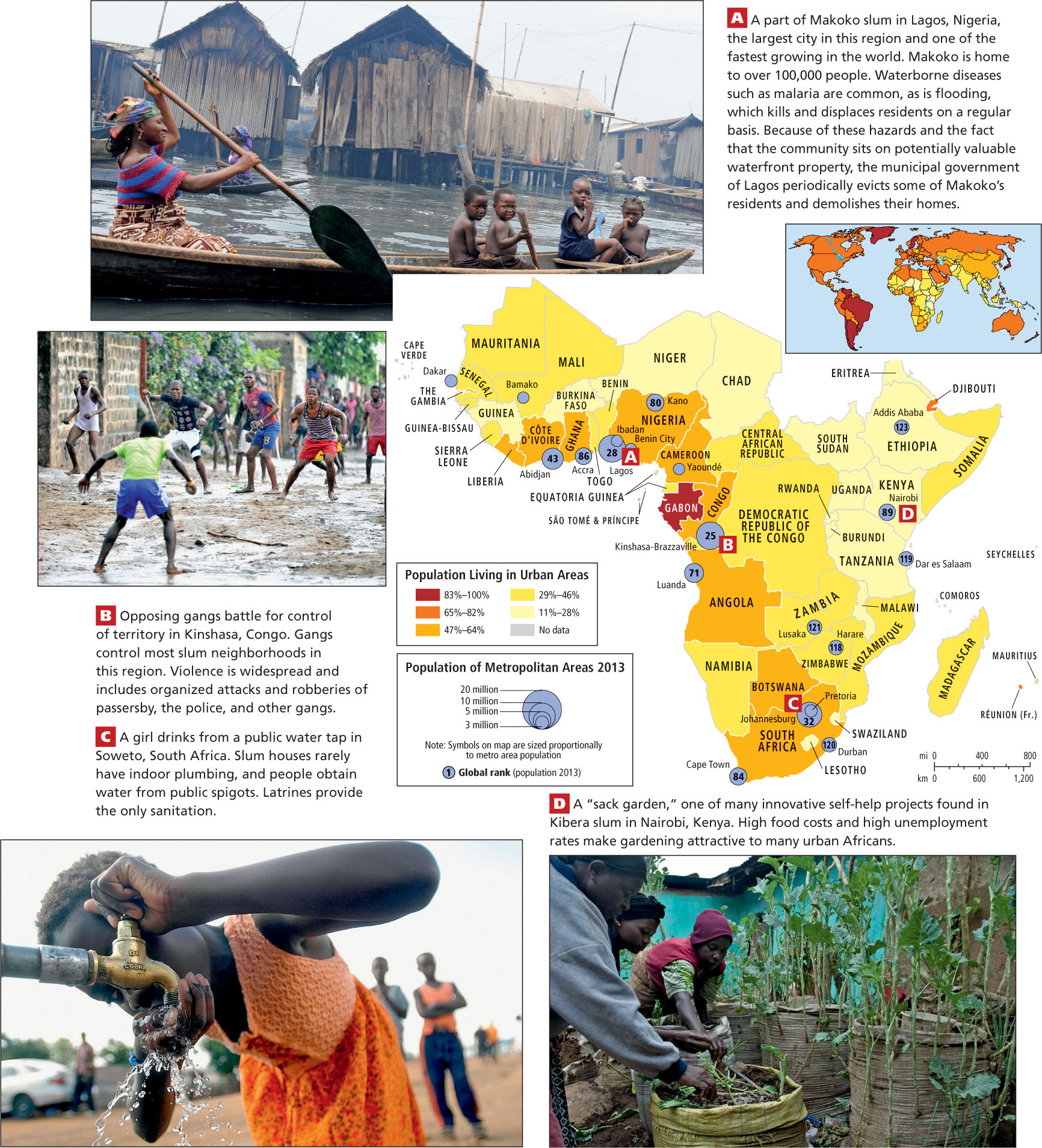

Population, Urbanization, Food, and Water: In part because of lower infant mortality rates and the higher cost of rearing children in cities, urbanization has the positive effect of encouraging families to limit births. Nevertheless, urbanization often happens in an uncontrolled fashion, leaving many people to reside in impoverished slums without adequate services, sufficient food, and clean water.

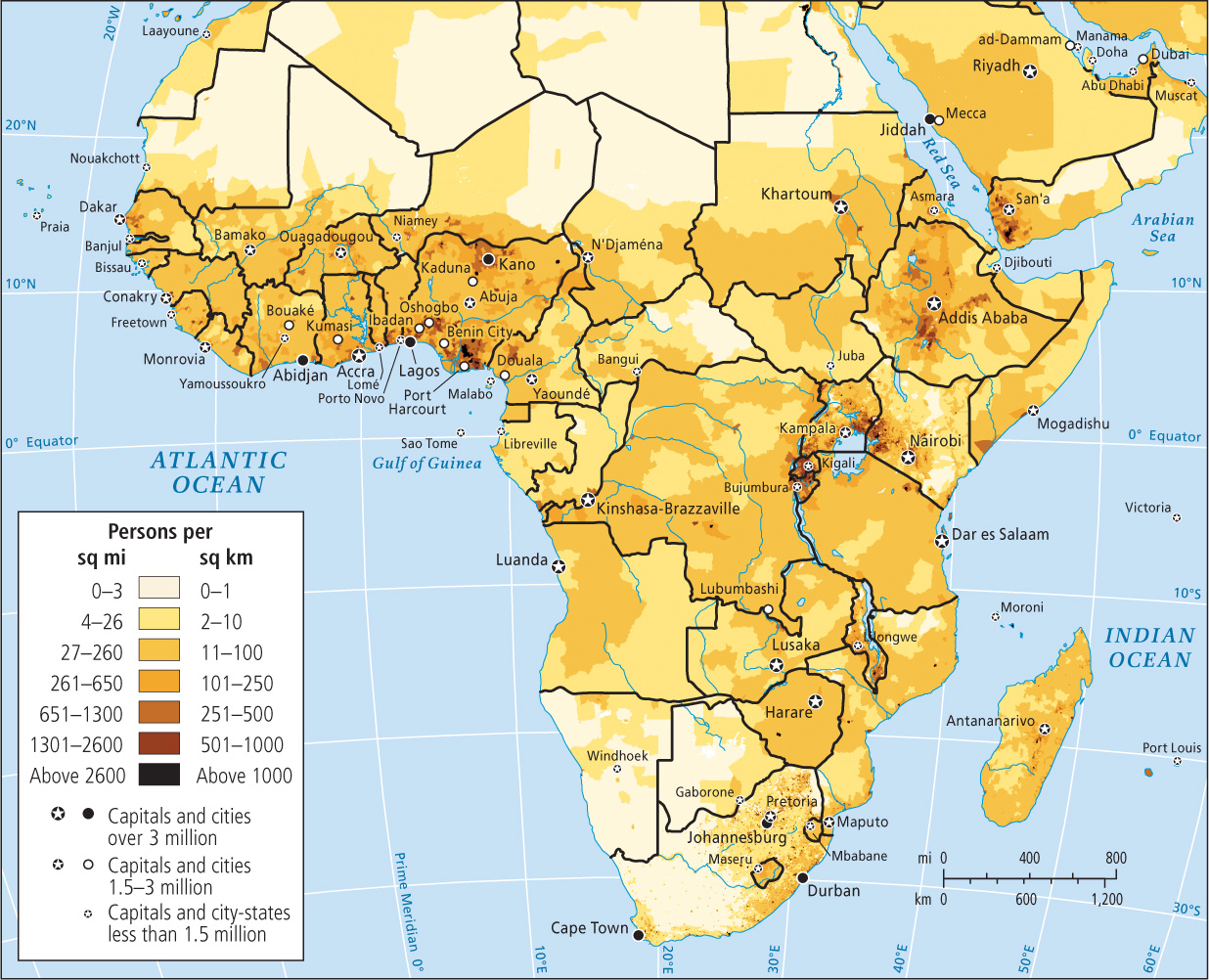

In fewer than 50 years, sub-Saharan Africa’s population has more than quadrupled, growing from about 200 million in 1960 to 828 million in 2009, to slightly under 1 billion in 2013. By 2050, the population of this region could reach just over 2 billion. Nonetheless, contrary to the perception outsiders often hold, Africa as a whole is much less densely populated than most of Europe and Asia—36 people per square kilometer, compared to the global average of 51 people per square kilometer. If fertility rates remain high, though, places that are relatively uncrowded now may change dramatically over the next few decades (Figure 7.22; see also Figure 1.8). In some rural areas, the population density may far exceed the carrying capacity of the land, which will lead to the impoverishment of subsistence farmers. Increasingly, however, Africa’s population is becoming concentrated in a few urban areas, such as the cities along the Gulf of Guinea coast in West Africa.

Right now, sub-Saharan Africa’s annual rate of natural increase (2.6 percent) is the highest in the world; even so, overall rates are slowing in nearly every country, especially in urban areas. Nonetheless, people continue to have more children than would be necessary to simply maintain population numbers. Birth rates are as high as they are because many Africans view children as both an economic advantage and a spiritual link between the past and the future. Childlessness is considered a tragedy, as children ensure a family’s genetic and spiritual survival.

Large families are also viewed as having economic value, as children and young adults still perform important work on family farms and in family-scale industries. Moreover, in this region of generally poor health care and the resultant high incidence of infant mortality, parents may have extra children in the hope of raising a few to maturity. In all but a few countries, the demographic transition—the sharp decline in births and deaths that usually accompanies economic development (see Figure 1.10)—has barely begun, and more people now survive long enough to reproduce than did in the past. If, however, Africa is on the brink of a development surge, fertility rates could decline quite sharply as women choose roles other than motherhood.

At least five countries in the region have gone through the demographic transition. In South Africa, Botswana, Seychelles, Réunion, and Mauritius (the last three being small island countries off Africa’s east coast), circumstances have changed sufficiently to make smaller families desirable and attainable. In all five countries, per capita incomes are five to ten times the sub-Saharan average of U.S.$2000. Advances in health care have cut the infant mortality rate to less than half the regional average of 88 infant deaths per 1000 live births; because of this, parents can have only a few children and expect them to live to adulthood. The circumstances of women in these five countries have also improved, as reflected in female literacy rates of about 80 to 90 percent, compared to the regional average of 54 percent. Research also shows that opportunities for women to work outside the home at decent-paying jobs are greater in these countries than in the rest of the region. Thus, many women are choosing to use contraception because they have life options beyond motherhood. Indeed, the percent of married women using contraception in these five countries is double or even triple the rate for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, which is only 22 percent (the world average is 61 percent).

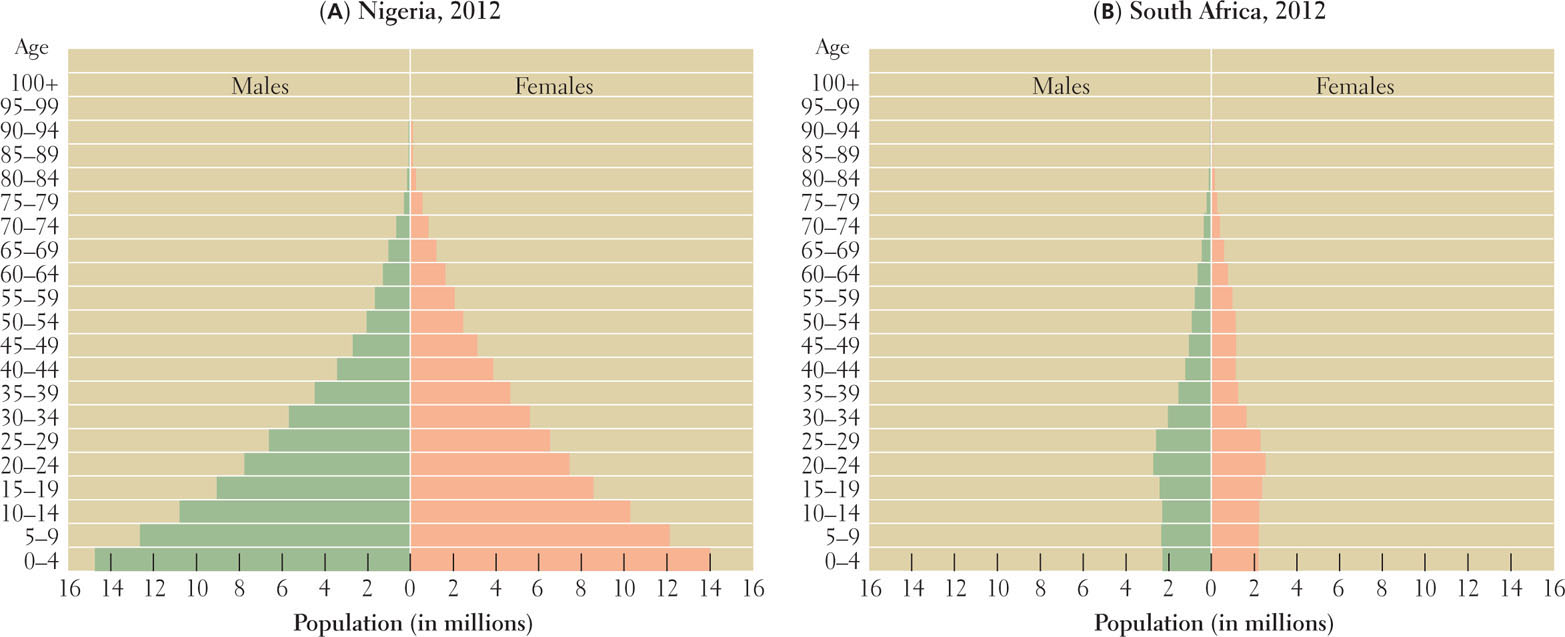

The population pyramids shown in Figure 7.23 demonstrate the contrast between countries that are growing rapidly, such as Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country (with 170.1 million people and a natural increase rate of 2.6 percent) and countries that have already gone through the demographic transition, such as South Africa (with 51.1 million people and a natural increase rate of 0.6 percent). Nigeria’s pyramid is very wide at the bottom because over half the population is under the age of 20. In just 15 years, this entire cohort will be of reproductive age. Only 15 percent of Nigerian women use any sort of birth control.

In contrast to Nigeria, South Africa’s pyramid has contracted at the bottom because its birth rate has dropped from 35 per 1000 to 21 per 1000 over the last 20 years. This decrease is primarily an effect of economic and educational improvements as well as social changes that have come about since the end of apartheid (1994). It is likely to persist as the advantages of smaller families, especially to women, become clear. The birth rate decrease is all the more remarkable because contraception is used by only 60 percent of South African women. Part of the birth rate decrease in South Africa is probably a consequence of the high rate of HIV among young adults there.

Urbanization and Population Growth

Sub-Saharan Africa is undergoing a massive shift in population from tiny rural settlements of a few houses to substandard residential facilities in dense urban areas. This has major implications for population growth. On average, rural sub-Saharan African women give birth to about six children, while urban African women give birth to four. Urban life strengthens all the factors that influence the demographic transition—increased education, economic opportunities, and better health care. While sub-Saharan Africa’s urban fertility rate of four children per woman is still almost double the world average, the demographic transition has only just begun, and indications are that urban sub-Saharan Africa’s birth rates will continue to decline.

Part of the reason that urban fertility rates are still as high as they are is that compared to cities in other regions, sub-Saharan Africa’s cities have relatively low living standards, especially with regard to access to clean water and sanitation (Figure 7.24A, C). Although improved over rural conditions, poverty and disease are still relatively widespread in cities, and because of the low access to birth control and the low levels of education and economic opportunities for women (when compared to global levels), urban families continue to have more than two children.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa, you will be able to answer the following questions about urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa:

Question

What do the types of houses, the water, and the boats suggest about the location of this slum?

What do the types of houses, the water, and the boats suggest about the location of this slum?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What are some factors that contribute to the prevalence of gangs in African slums?

What are some factors that contribute to the prevalence of gangs in African slums?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How might the lack of clean water and sanitation create an incentive for people to have large families?

How might the lack of clean water and sanitation create an incentive for people to have large families?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How does this project in Nairobi embody the idea of "self-reliant development"?

How does this project in Nairobi embody the idea of "self-reliant development"?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Urban Food Gardens

A 2012 UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) report, “The Greening of African Cities,” emphasizes that the growing of produce in and around cities, on even the tiniest scraps of land, has an advantage over both rural market gardening and imported food in supplying urban folks with safe, nutritious food. Fruits and vegetables can be highly perishable, so if urban consumers can produce their own food, they are likely to eat better, to create less waste, and to have lower food transport costs. Also, food waste can be immediately recycled as compost, reducing or eliminating the need for fertilizers; the greenbelts created by urban gardens can reduce urban air and water pollution.

Country-to-Country and Rural-to-Urban Migration

The migration of sub-Saharan people looking for work in North Africa, Europe, Turkey, or the United States is now a familiar phenomenon, but the vast majority of the African migrants who are seeking work or escaping violence move from country to country within the continent. In 2005, the United Nations estimated that there were 17 million such internal migrants, most going to West Africa and Southern Africa, because jobs are more numerous in both areas. Country-to-country migrants often go to rural areas as agricultural laborers, but increasingly more educated migrants seek out cities. The five sub-Saharan African countries with the largest number of immigrants in 2005 were Côte d’Ivoire (2.4 million), Ghana (1.7 million), South Africa (1.1 million), Nigeria (1.0 million), and Tanzania (0.8 million). Together they have 40 percent of the migrants in Africa. Even though the migrants typically make few demands, the impact on receiving countries that are unable to provide adequately for their own citizens is substantial. Like migrants who leave the continent, internal migrants live frugally and send much of their earnings home to families.

Although urban birth rates remain relatively high, migration from rural areas to cities is actually the biggest factor behind sub-Saharan cities’ growth rate of 5 percent per year, the highest rate in the world. In the 1960s, only 15 percent of sub-Saharan Africans lived in cities; now about 37 percent do (see the Figure 7.24 map). Estimates are that by 2030, half of all Africans will be urban dwellers. In 1960, just one sub-Saharan African city—Johannesburg, South Africa—had more than 1 million people; in 2009, fifty-two did. The largest sub-Saharan African city is Lagos, Nigeria, where various estimates put the population at between 11 and 13 million; by 2020, Lagos is projected to have 20 million people (see the Figure 7.24 map). Much of this growth is taking place in primate cities (see Chapter 3, page 161). For example, Kampala, Uganda, with 1.8 million people, is almost 10 times the size of Uganda’s next largest city, Gulu.

Because governments and private investors have paid little attention to the need for affordable housing, most migrants have to construct their own dwellings using found materials. The vast, unplanned, one-story slums surrounding older urban centers house 72 percent of Africa’s urban population. Transportation in these huge and shapeless settlements is a jumble of government buses and private vehicles, and in waterfront locales, boats (see Figure 7.24A). Parents often have to travel long hours through extremely congested traffic to reach distant jobs, getting much of their sleep while sitting on a crowded bus and leaving their children unsupervised and susceptible to the influence of gangs (see Figure 7.24B).

Food Security in Urban Areas

Food supplies for urban residents can be brought in from the countryside, or be imported from distant lands, or, as is increasingly common, be grown in cities by urban residents. In some cities, residents have taken the initiative to produce their own food in the tiny spaces between houses (see Figure 7.24D) and in the wastelands that surround urban shantytowns.

If urban gardening is to become a viable food security solution, some regulation will be necessary. At present, urban farmers may be using brownfields—land where the soil is contaminated by past industrial activities and the wastewater used to irrigate may not be safe—but this can be corrected. Rainwater can be harvested or treated wastewater can be used to safely supply needed nutrients to the plants; raised cultivation beds can be sealed off from contaminated soil. Also, because few urban gardeners have title to the land they cultivate, urban garden land must not be subject to confiscation for development without properly compensating the gardeners and alloting them replacement land. Finally, the use, and especially overuse, of fertilizers must be controlled; this can be done through educating farmers about them. Adult education courses reminiscent of those taught to home gardeners in the United States during World War II could revolutionize food production in African cities.

The Scarcity of Clean Water in Sub-Saharan Cities

Public health is a major urban concern, as many water distribution systems are susceptible to being contaminated by harmful bacteria from untreated sewage (see Figure 7.24C). Only the largest sub-Saharan African cities have sewage treatment plants, and few of these extend to the slums that surround them. The result is frequent outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. It is estimated that unsafe water and sanitation facilities result in an annual loss of $28.4 billion in Africa alone.

Although the safety of city water supplies is improving, there are frequent periodic water shortages in as many as 11 out of 14 sub-Saharan cities. To control usage during a crisis, city officials limit service to a few hours a day, causing people to store water in vessels that may become contaminated. Recent reassessments of the availability of groundwater resources may eventually alleviate these urban water shortages, but recall that the natural distribution of groundwater does not easily match up with the location of the big cities (see Figure 7.9).

Population and Public Health

Infectious diseases, including HIV-AIDS, are by far the largest killers in sub-Saharan Africa, responsible for about 50 percent of all deaths. Some diseases are linked to particular ecological zones. For example, people living between the 15th parallels north and south of the equator are most likely to be exposed to sleeping sickness (trypano-somiasis), which is spread among people and cattle by the bites of tsetse flies. The disease attacks the central nervous system and, if untreated, results in death. Several hundred thousand Africans suffer from sleeping sickness, and most of them are not treated because they cannot afford the expensive drug therapy.

Africa’s most common chronic tropical diseases, schistosomiasis and malaria, are linked to standing fresh water. Thus, their incidence has increased with the construction of dams and irrigation projects. Schistosomiasis is a debilitating, though rarely fatal, disease that affects about 170 million sub-Saharan Africans. It develops when a parasite carried by a particular freshwater snail enters the skin of a person standing in water. Malaria, spread by the anopheles mosquito (which lays its eggs in standing water), is more deadly. The disease kills at least 1 million sub-Saharan Africans annually, most of them children under the age of 5. Malaria also infects millions of adult Africans who are left feverish, lethargic, and unable to work efficiently because of the disease.

Until recently, relatively little funding was devoted to controlling the most common chronic tropical diseases. Now, however, major international donors are funding research in Africa and elsewhere. More than 60 research groups in Africa are working on a vaccine that will prevent malaria in most people. The distribution of simple, low-cost, and effective mosquito nets is also reducing the transmission rates of malaria.

Polio is not a tropical disease, but it remains a challenge in many sub-Saharan countries, despite having been controlled in Europe and the Americas some decades ago. Part of the problem is a lack of science education. For example, in Nigeria in the early 2000s, Muslim clerics in the north of the country preached that a polio vaccination project was a Western plot to sterilize African children. The incidence of the disease shot up and, in 2012, more than 90 cases were reported. Now, after public education efforts, the clerics have relented and instead preach that vaccination is required of all children. A successful polio eradication program must include public education, testing, improved sewage treatment, cleaning up of standing water, and an orderly vaccination program.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

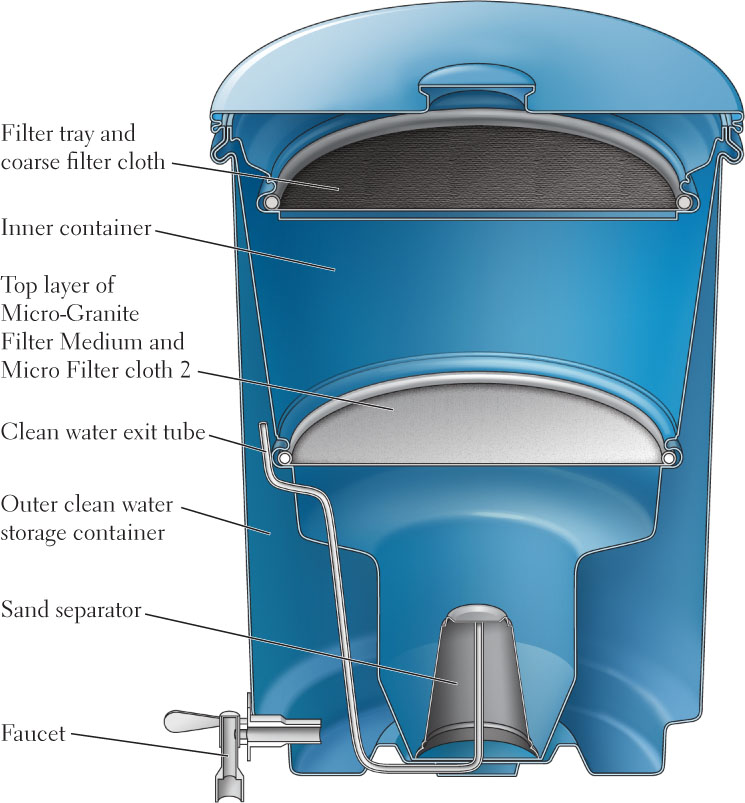

The TivaWater Jug

The problem of unsafe water for households may have a solution that is simple, affordable, and may create local jobs. A for-profit group, working with grassroots organizations in Uganda but subsidized by American investors, has designed a simple plastic jug, called the TivaWater jug, with an interior sand and clay filtering device that purifies water (Figure 7.25). The jug is made to be affordable to urban poor people in Ugandan shantytowns. In line with modern self-sufficiency development theory for Africa, the jug, while initially made in the United States, is now manufactured in Uganda, is sold and distributed by small businesses there, and will eventually be exported by Ugandans to other African countries.

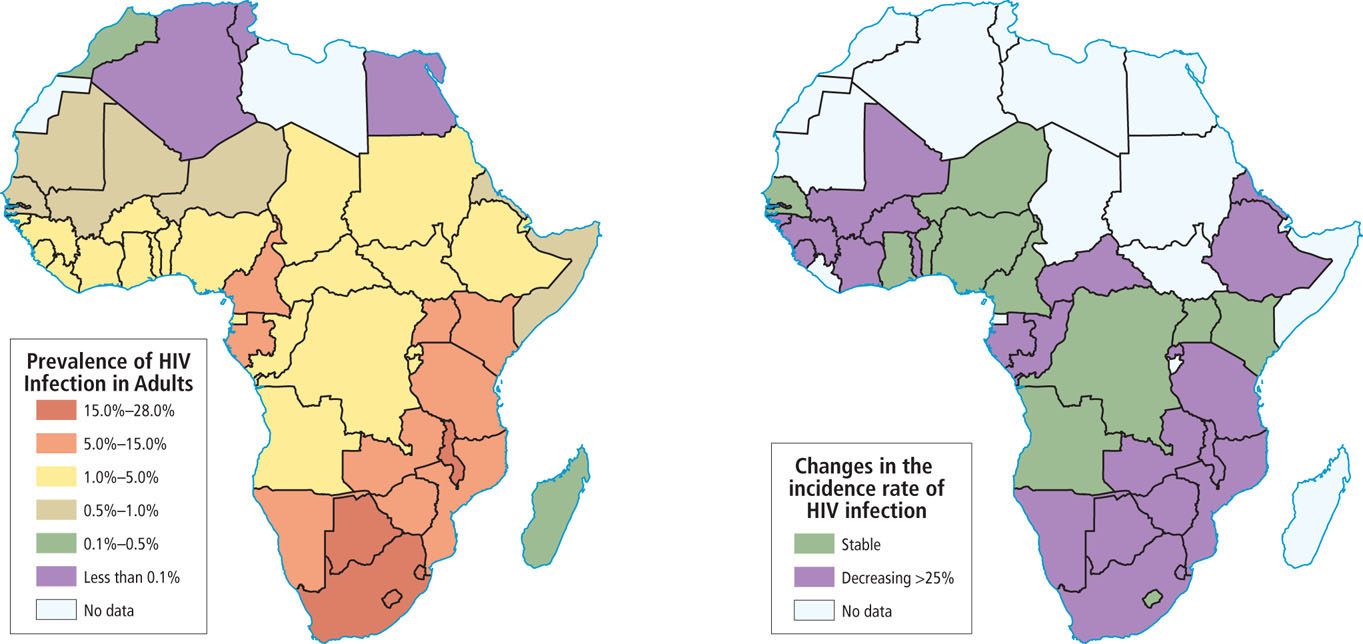

HIV-AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

A leading cause of death in Africa, and the leading cause of death for women of reproductive age, is acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Figure 7.26). As of 2010, more than 16 million sub-Saharan Africans had died of the disease, and as many as 80 million more AIDS-related deaths are expected by 2025. In 2010, sub-Saharan Africa had two-thirds of the estimated worldwide total of 33 million people living with HIV. In Botswana, one of the richest countries in Southern Africa, nearly 29.2 percent of the adult female population is infected. The Southern Africa region alone accounted for 31 percent of global AIDS deaths in 2010. While the epidemic is subsiding a bit, it has significantly constrained economic development.

Worldwide, women account for half of all people living with HIV, but in Africa, HIV-AIDS affects women more than men: 59 percent of the region’s HIV-infected adults are women. The reasons for this pattern are related to the social status of women in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere.

The rapid urbanization of Africa has hastened the spread of HIV, which is much more prevalent in urban areas. It is not uncommon for poor, new urban migrants, removed from their village support systems, to become involved in the sex industry in order to survive economically. In some cities, virtually all sex workers are infected. Meanwhile, many urban men, especially those with families back in rural villages, visit prostitutes on a regular basis. These men often bring HIV back to their rural homes. As transportation between cities and the countryside has improved, bus and truck drivers have also become major carriers of HIV to rural villages.

A number of myths and social taboos surround HIV-AIDS and exacerbate the problem of controlling the spread of the disease, making education a key component in combating the epidemic. For example, some men think that only sex with a mature woman can result in infection, so very young girls are increasingly sought as sex partners (sometimes referred to as “the virgin ‘cure’”). Elsewhere, infection is considered such a disgrace that even those who are severely ill refuse to get tested, yet they remain sexually active.

The Social Costs of HIV-AIDS

Across the continent, the consequences of the HIV-AIDS epidemic are enormous. Children contract HIV primarily in utero or from nursing; just over 400 children under the age of 15 die each day from AIDS-related causes. Millions of parents, teachers, skilled farmers, craftspeople, and trained professionals have been lost. More than 15 million children have been orphaned; many have no family left to care for them or to pass on vital knowledge and life skills. The disease has severely strained the health-care systems of most countries. Demand for treatment is exploding, drugs are prohibitively expensive, and many health-care workers themselves are infected. Because so many young people are dying of AIDS, decades of progress in improving the life expectancy of Africans have been erased. For example, in 1990, adult life expectancy in South Africa was 63 years, but in 2012 it was 54 years.

HIV-AIDS Education and Medication

The most effective means of prevention are the massive education programs that lower rates of infection among those who can read and understand explanations about how HIV is spread. For example, Senegal started HIV-AIDS education in the 1980s, and levels of infection there have so far remained low. Major education campaigns in Uganda lowered the incidence of new HIV infections from 15 percent to just 4.1 percent between 1990 and 2004. By contrast, infection rates have soared in areas such as South Africa, where a few top politicians have put forth untenable theories about the causes of HIV infection or have denied that HIV-AIDS is a problem.

HIV-AIDS medications (known as antiretroviral therapy) are prohibitively expensive for families in sub-Saharan Africa. The United Nations and a number of private philanthropies cover some of the costs. The medications are not a cure and must be taken daily for the rest of one’s life, but they do make it possible to live with the disease. Pharmaceutical firms in India and China and elsewhere have come out with generic antiretroviral versions that have reduced the cost to about $350 per year, about one-sixth of the average annual income in the region. About five out of every six recipients worldwide are in sub-Saharan Africa, and most of those are in Southern Africa. As yet, only half of those who need the medicines are receiving them; the goal is for all of those with HIV-AIDS to be covered by 2015. The cost to the world of keeping parents alive with antiretroviral therapy is far less than dealing with the social effects of millions of orphans.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The overall low population density figures in sub-Saharan Africa—36 people per square kilometer, compared to the global average of 51 people per square kilometer—can be misleading. Densities are extremely high in some places and very low in less habitable areas.

The overall low population density figures in sub-Saharan Africa—36 people per square kilometer, compared to the global average of 51 people per square kilometer—can be misleading. Densities are extremely high in some places and very low in less habitable areas. Of all the world regions, populations are growing fastest in sub-Saharan Africa. The demographic transition is taking hold in a few of the more prosperous countries where better health care and lower levels of child mortality, along with more economic and educational opportunities for women, are enabling women to pursue careers and to choose to have fewer children.

Of all the world regions, populations are growing fastest in sub-Saharan Africa. The demographic transition is taking hold in a few of the more prosperous countries where better health care and lower levels of child mortality, along with more economic and educational opportunities for women, are enabling women to pursue careers and to choose to have fewer children. Geographic Insight 5Population, Urbanization, Food, and Water While urbanization helps reduce the birth rate, too often it leaves many people to reside in slums in poverty and without proper food, water, and adequate services. Largely ignored by most governments, people in slums survive by providing for themselves, as exemplified by the emerging urban garden movement.

Geographic Insight 5Population, Urbanization, Food, and Water While urbanization helps reduce the birth rate, too often it leaves many people to reside in slums in poverty and without proper food, water, and adequate services. Largely ignored by most governments, people in slums survive by providing for themselves, as exemplified by the emerging urban garden movement. Sub-Saharan Africa has higher rates of infectious diseases than does any other region in the world, with the world’s worst epidemics of malaria, polio, schistosomiasis, sleeping sickness, and HIV-AIDS.

Sub-Saharan Africa has higher rates of infectious diseases than does any other region in the world, with the world’s worst epidemics of malaria, polio, schistosomiasis, sleeping sickness, and HIV-AIDS.

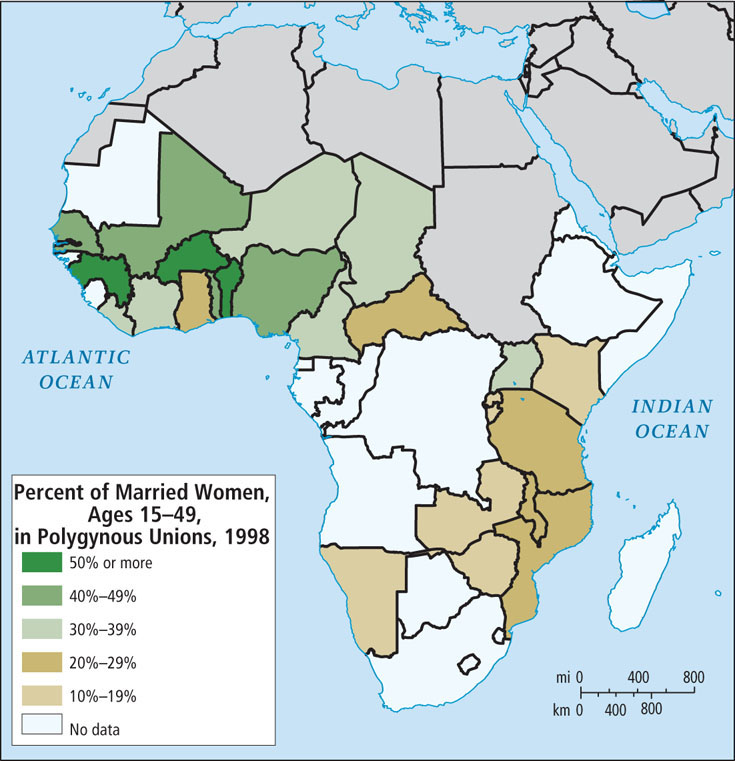

Gender Issues

Long-standing African traditions dictate a fairly strict division of labor and responsibilities between men and women. In general, women are responsible for domestic activities, including raising the children, attending to the sick and elderly, and maintaining the house. Women collect water and firewood and prepare nearly all the food. Men are usually responsible for preparing land for cultivation. In the fields intended to produce food for family use, women sow, weed, and tend the crops as well as process them for storage. In the fields where cash crops are grown, men perform most of the work and retain control of the money earned. When husbands in search of cash income migrate to work in mines or in urban jobs, women take over nearly all of the agricultural work, often using simple hand tools, not machines or even draft animals. When there are small agricultural surpluses or handcrafted items to trade, it is women who transport and sell them in the market. Throughout Africa, married couples often keep separate accounts and manage their earnings as individuals, but when a wife sells her husband’s produce at the market, she usually gives the proceeds to him.

polygyny the practice of having multiple wives

Women face significant sexual and physical abuse in the home and also during civil unrest, when rape and beatings are more common. Many of the female politicians who have come to power in the last decade are now addressing these issues. Most have emphasized the need for more women to be in the position to influence and enforce policies to reduce violence against women. In Liberia, for instance, President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf has defined women’s rights as a national security issue. Liberia has recruited women to serve in both the police and the armed forces.

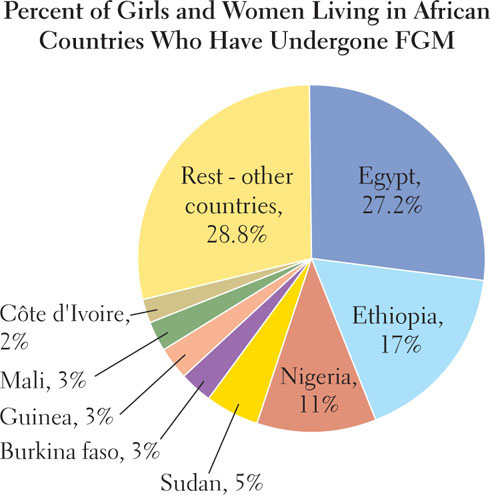

female genital mutilation (FGM) removing the labia and the clitoris and sometimes stitching the vulva nearly shut

171. FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION STILL COMMON IN SOMALILAND

171. FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION STILL COMMON IN SOMALILAND

The practice is probably intended to ensure that a female is a virgin at marriage and that she thereafter has a low interest in intercourse other than for procreation. While in decline today, FGM is still widespread among some groups. Among the Kikuyu of Kenya, 40 years ago, nearly all females would have had FGM, but today only about 40 percent do. Kikuyu women’s rights leaders have had some success in curbing FGM by replacing it with right-of-passage ceremonies that joyously mark a girl’s transition to puberty.

Many African and world leaders have concluded that the practice is an extreme human rights abuse, and it is now against the law in 16 countries. The most successful eradication campaigns are those that emphasize the threat FGM poses to a woman’s health, thus making it socially acceptable to not undergo this ritual. The World Health Organization in 2008 took a strong stand against FGM, saying:

Female genital mutilation has been recognized as discrimination based on sex because it is rooted in gender inequalities and power imbalances between men and women and inhibits women’s full and equal enjoyment of their human rights. It is a form of violence against girls and women, with physical and psychological consequences.

World Health Organization, Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation—An Interagency Statement

(Geneva: World Health Organization Press, 2008), p. 10.

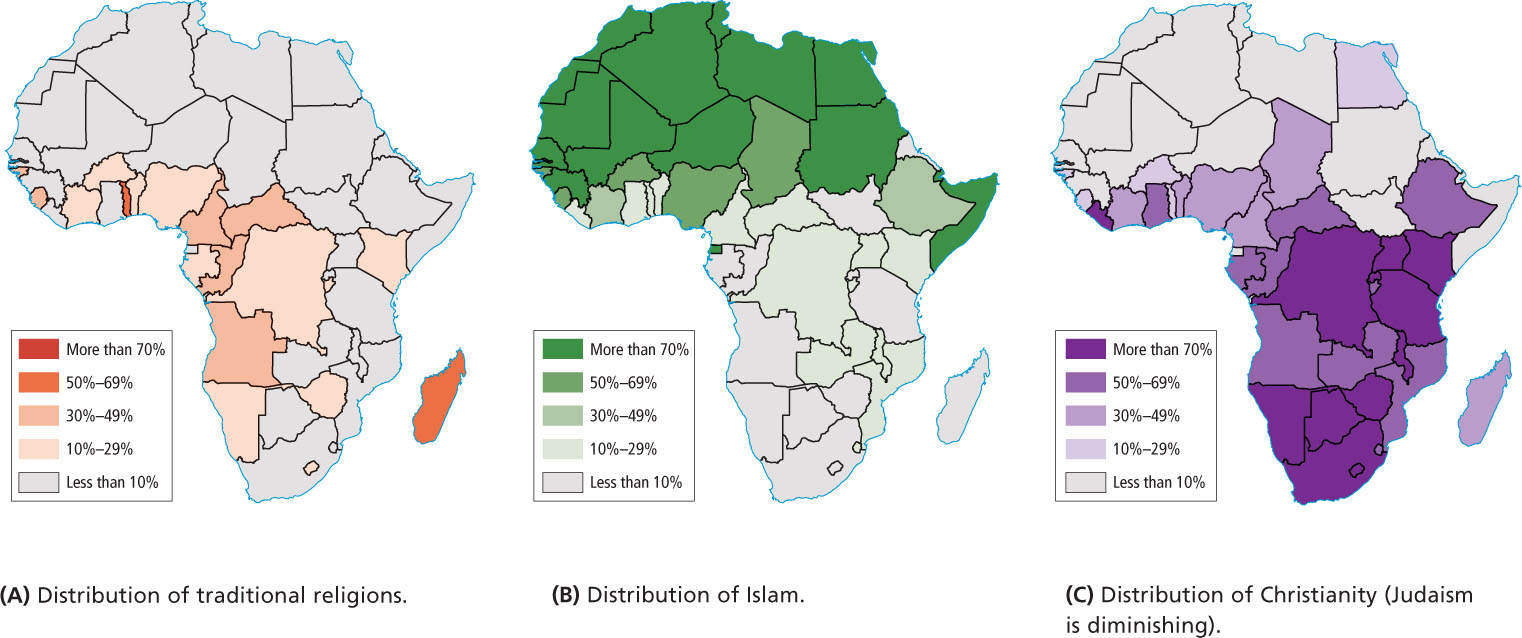

Religion

Africa’s rich and complex religious traditions derive from three main sources: indigenous African belief systems (many of them animist), Islam, and Christianity.

Indigenous Belief Systems

Traditional African religions, found in every part of the continent, are probably the most ancient on Earth, since this is where human beings first evolved. Figure 7.29 highlights the countries in which traditional beliefs remain particularly strong. Traditional beliefs and rituals often seek to bring departed ancestors into contact with living people, who in turn are the connecting links in a timeless spiritual community that stretches into the future. The future is reached only if present family members procreate and perpetuate the family heritage through storytelling.

animism a belief system in which spirits, including those of the deceased, are thought to exist everywhere and to offer protection to those who pay their respects

Religious beliefs in Africa, as elsewhere, continually evolve as new influences are encountered. If Africans convert to Islam or Christianity, they commonly retain aspects of their indigenous religious heritage. The three maps in Figure 7.29 show a spatial overlap of belief systems, but they do not convey the philosophical blending of two or more faiths, which is widespread. In the Americas, the African diaspora has influenced the creation of new belief systems developed from the fusion of Roman Catholicism and African beliefs. Voodoo in Haiti, Santería in Cuba, and Candomblé in Brazil (see Chapter 3) are examples of this fusion.

Islam and Christianity

Islam began to extend south of the Sahara in the first centuries after Muhammad’s death in 632 c.e., and today, about one-third of sub-Saharan Africans are Muslim (see Figure 7.29B). Islam is now the predominant religion throughout the Sahel and parts of East Africa, where Muslim traders from North Africa and Southwest Asia brought the religion. Powerful Islamic empires have arisen here since the ninth century. The latest of these empires challenged European domination of the region in the late nineteenth century.

Today about half of Africans are Christian. Christianity first came to the region via Egypt and Ethiopia shortly after the time of Christ, well before it spread throughout Europe (see Figure 7.29C). Christianity did not come to the rest of Africa until nineteenth-century missionaries from Europe and North America became active along the west coast. Many Christian missionaries provided the education and health services that colonial administrators had neglected. In the twentieth century, old-line established churches began to gain adherents in Africa. The Anglican Church (Church of England) grew so rapidly that by 2000, Anglicans in Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria outnumbered those in the United Kingdom. The Anglican Church in Africa attracts the educated urban middle class.

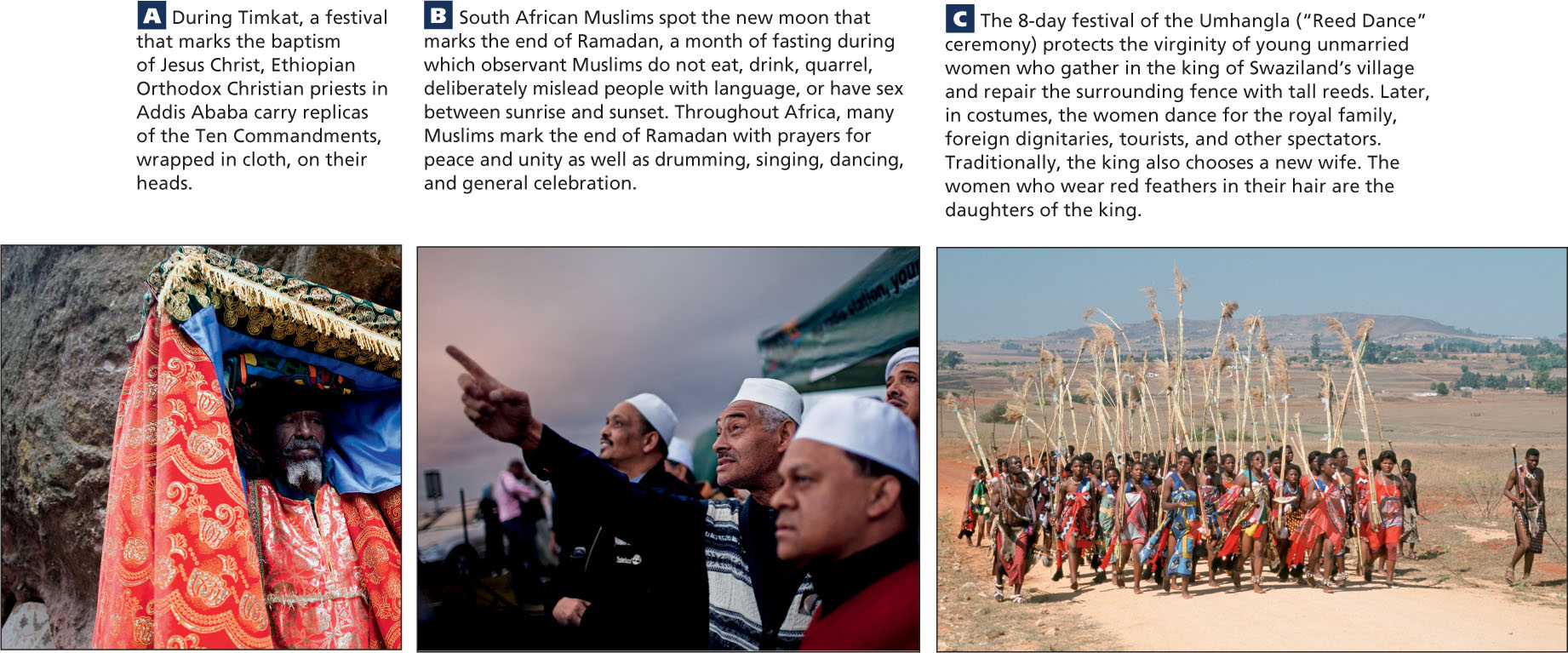

Festivals across the continent celebrate the variety of African religious traditions. As is the case with festivals everywhere, such events offer an opportunity to represent ideal versions of culture, a chance to revel in joy and renewed religious dedication, or a chance to make important social contacts, reinforce identity, and perform community service (Figure 7.30).

Evangelical Christianity and the Gospel of Success

In contrast to the Anglican Church, modern evangelical versions of Christianity appeal to the less-educated, more recent urban migrants—the most rapidly growing segment of the population. These independent, evangelical sects interpret Christianity as being aligned with traditional beliefs in the importance of sacrificial gifts to spiritual leaders and ancestors, the power of miracles, and the idea that devotion brings wealth. The result is one of the world’s fastest-growing Christian movements.

VIGNETTE

Preachers at the Miracle Center in Kinshasa describe the Gospel of Success forcefully: “The Bible says that God will materially aid those who give to Him…. We are not only a church, we are an enterprise. In our traditional culture you have to make a sacrifice to powerful forces if you want to get results. It is the same here.”

Generous gifts to churches are promoted as a way to bring divine intervention to alleviate miseries, whether physical or spiritual. Practitioners donate food, television sets, clothing, and money. One woman gave 3 months’ salary in the hope that God would find her a new husband.

Like all religious belief systems, the gospel of success is best understood within its cultural context. Many of the believers, new to the city, feel isolated and are looking for a supportive community to replace the one they left behind. In return for material contributions to the church and volunteer services, members receive social acceptance and community assistance in times of need.

Ethnicity and Language

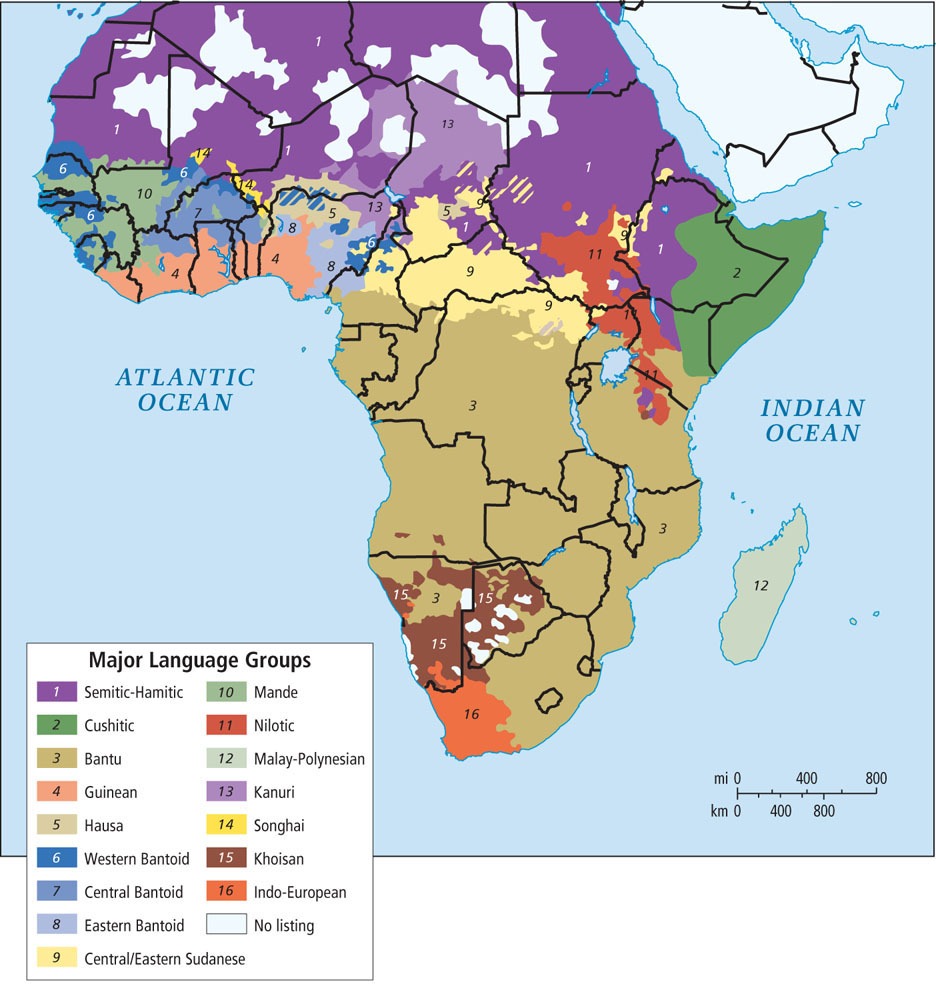

Ethnicity, as we have seen throughout this book, refers to the shared language, cultural traditions, and political and economic institutions of a group. The map of Africa in Figure 7.31 shows a rich and complex mosaic of languages. Yet despite its complexity, this map does not adequately depict Africa’s cultural diversity (compare it with Figure 7.20 on Nigeria).

Most ethnic groups have a core territory in which they have traditionally lived, but very rarely do groups occupy discrete and exclusive spaces. Often several groups share a space, practicing different but complementary ways of life and using different resources. For example, one ethnic group might be subsistence cultivators, another might herd animals on adjacent grasslands, and a third might be craft specialists working as weavers or metalsmiths.

People may also be very similar culturally and occupy overlapping spaces but identify themselves as being from different ethnic groups. Hutu farmers and Tutsi cattle raisers in Rwanda share similar occupations, languages, and ways of life. However, European colonial policies purposely exaggerated ethnic differences as a method of control, assigning a higher status to the Tutsis. Hutus and Tutsis now think of themselves as having very different ethnicities and abilities. In the 1990s and again in 2004, the Hutu-run government encouraged attacks on the minority Tutsi people. Hutus were also killed, but those killed tended to be people who opposed the genocide. The best estimates indicate that more than 1 million people, most of them Tutsis, died during the two genocide catastrophes.

Some African countries have only a few ethnic groups; others have hundreds. Cameroon, sometimes referred to as a microcosm of Africa because of its ethnic complexity, has 250 different ethnic groups. Different groups often have extremely different values and practices, making the development of cohesive national policies difficult. Nonetheless, the vast majority of African ethnic groups have peaceful and supportive relationships with one another.

lingua franca language of trade

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Gender relationships in sub-Saharan Africa are complex and variable, but in this region as in others, women are generally subordinate and are often physically abused. Nonetheless, change is underway.

Gender relationships in sub-Saharan Africa are complex and variable, but in this region as in others, women are generally subordinate and are often physically abused. Nonetheless, change is underway. Female genital mutilation has terrible consequences for women’s health. It has been recognized as sexual discrimination because it is rooted in gender inequalities and power imbalances between men and women.

Female genital mutilation has terrible consequences for women’s health. It has been recognized as sexual discrimination because it is rooted in gender inequalities and power imbalances between men and women. Traditional African religions are among the most ancient on Earth and are found in every part of the continent. Today, however, about one-third of sub-Saharan Africans are Muslim and about half are Christian. Many in the evangelical movement, a subset of Christianity, promote the Gospel of Success as a way of life.

Traditional African religions are among the most ancient on Earth and are found in every part of the continent. Today, however, about one-third of sub-Saharan Africans are Muslim and about half are Christian. Many in the evangelical movement, a subset of Christianity, promote the Gospel of Success as a way of life. Sub-Saharan Africa is a mosaic of more than 1000 languages that are roughly similar to the mosaic of ethnic groups. Hausa, Arabic, and Swahili are now the most commonly used languages of trade.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a mosaic of more than 1000 languages that are roughly similar to the mosaic of ethnic groups. Hausa, Arabic, and Swahili are now the most commonly used languages of trade.