8.1 8 South Asia

8.1.1 Geographic Insights: South Asia

Geographic Insights: South Asia

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Climate Change and Water: Climate change puts more lives at risk in South Asia than in any other region in the world, primarily due to water-related impacts. Sea level rise, droughts, floods, and the increased severity of storms imperil many urban and agricultural areas over the short term. Over the longer term, glacial melting threatens rivers and aquifers.

2. Gender and Population: The assumptions that males are more useful to families than females and that females must be supplied with a dowry have resulted in a devaluation of females, leading to a gender imbalance in populations across South Asia. Those who can afford in utero gender-identifying technology may abort female fetuses, while those with fewer resources sometimes commit female infanticide. As a result, adult males significantly outnumber adult females. A second relationship between gender and population is that when females are given opportunities to work outside the home, they tend to choose to have fewer children.

3. Food and Urbanization: Due to changes in food production systems in South Asia, food supplies and incomes of wealthy farmers have increased. Meanwhile, impoverished agricultural workers, displaced by new agricultural technology, have been forced to seek employment in cities, where they often end up living in crowded, unsanitary conditions, and must purchase food.

4. Globalization and Development: Globalization benefits populations unevenly. Educated and skilled South Asian workers with jobs in export-connected and technology-based industries and services enjoy better lives. Low-skilled workers, however, in both urban and rural areas, are left with demanding but very low-paying jobs.

5. Power and Politics: India, South Asia’s oldest, largest, and strongest democracy, has shown that democratic institutions can ameliorate conflict. Across the region, when ordinary people have been able to participate in policy-making decisions and governance—especially at the local level—intractable conflict has been diffused and combatants have been convinced to take part in peaceful political processes.

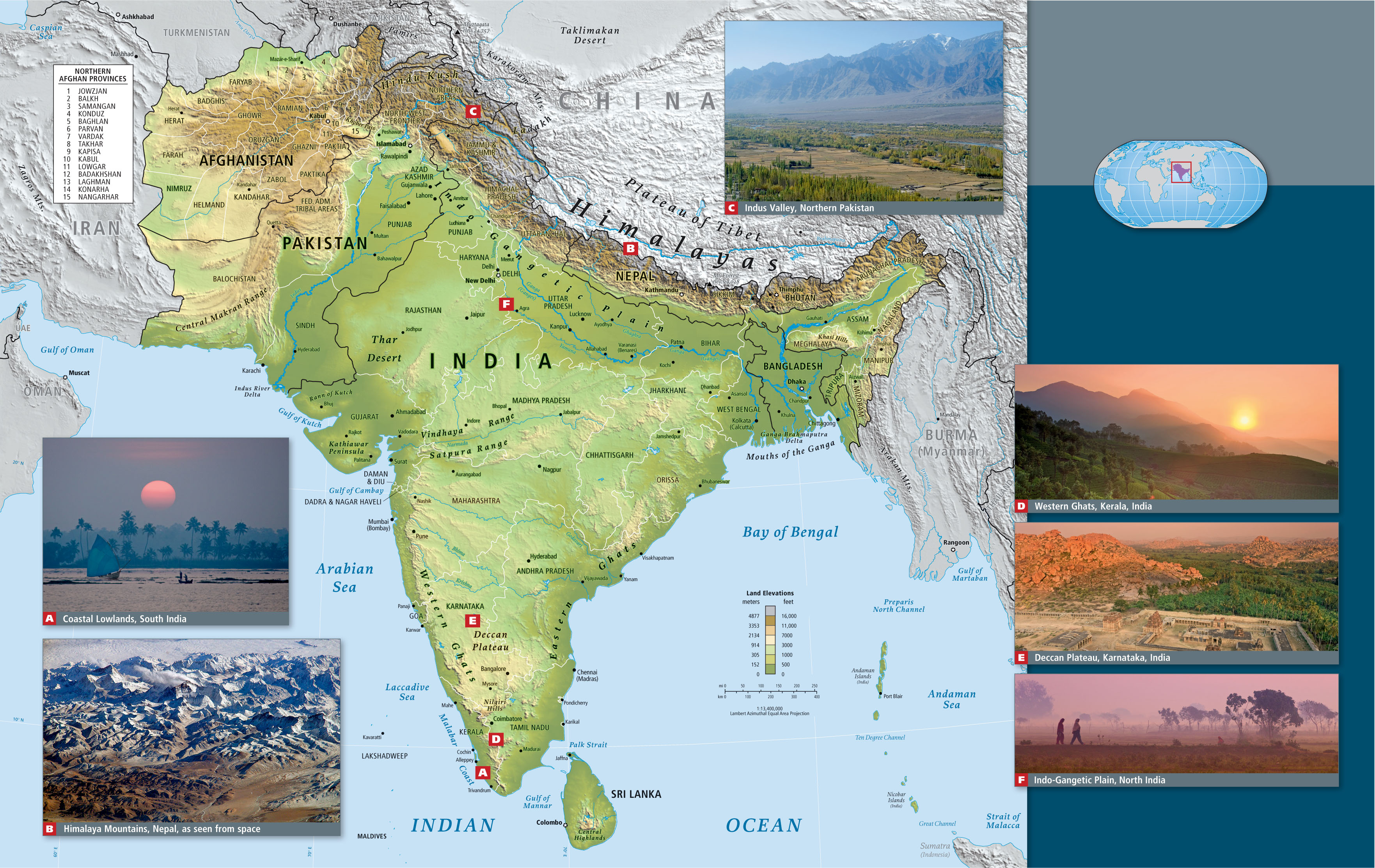

The South Asian Region

South Asia (see Figure 8.1), like so many of today’s world regions, began its modern history as the result of European colonization. During that time, economic, political, and social policies rarely put the needs of South Asian people first. Toward the end of the colonial era, major upheavals precipitated by departing colonists left the region with a legacy of distrust and difficult political borders that still lingers.

The nine thematic concepts highlighted in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Vignettes, like the one that follows, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

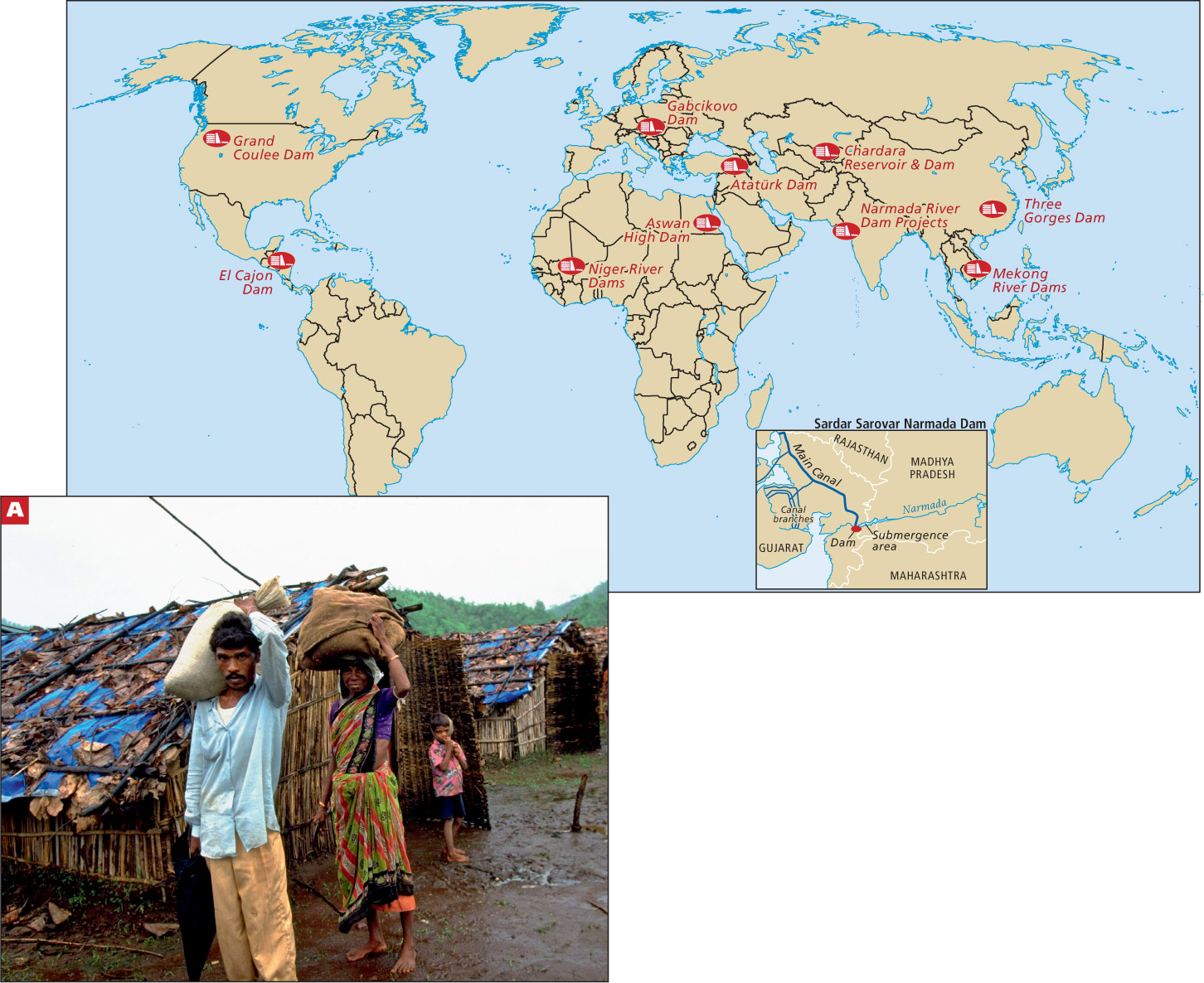

Narendra Modi, the chief minister of the state of Gujarat in western India (see Figure 8.1), is passionate about securing water for his state. In 2006, draped in garlands by well-wishers, he embarked on a flamboyant hunger strike to protest a decision by India’s national government in New Delhi to limit the height of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada River. Four Indian states lie in the drainage basin of the Narmada. Modi wanted to trap more water behind a higher dam so that as many as 50 million of his constituents in Gujarat would have greater access to water, primarily for irrigation. Gujarat produces much of the food needed by India’s west coast cities.

Far away in New Delhi, at the same time as Modi’s hunger strike, Medha Patkar, the leader of the “Save the Narmada River” movement, was in day 18 of her hunger strike protesting against the same dam. As water rose in the dam’s reservoir, 320,000 farmers and fishers in Madhya Pradesh, the state in which the reservoir is located, were being forced to move. Although Indian law requires that these people be given land or cash to compensate them for what they had lost, so far only a fraction had received any compensation. Some of the farmers demonstrated their objection by forfeiting their right to compensation and refusing to move, even as the rising waters of the reservoir consumed their homes. Forcibly removed by Indian police, many have since relocated to crowded urban slums.

Environmental and human rights problems have been at the heart of the Sardar Sarovar Dam controversy since the project began in 1961. The natural cycles of the Narmada River have been severely disturbed. Once a placid, slow-moving river—and one of India’s most sacred—the disruption of flows and the flooding upstream of the dam have caused massive die-offs of aquatic life, resulting in high unemployment levels among farmers and fishers. Many have also lost their homes to the rising reservoir waters (Figure 8.2A).

In addition to cost overruns that are more than three times original cost estimates, the ultimate benefits of the dam have also been called into question. A major justification for the dam was that, in addition to irrigation water, it would provide drinking water for 18 million people in the greater river basin as well as 1450 megawatts of electricity. But the demand for irrigation waters to serve drought-prone areas in the adjacent states of Gujarat and Rajasthan (see the Figure 8.2 map) is now so strong (and increasing due to climate warming) that there will not be sufficient water to generate even 10 percent of the 1450 planned megawatts on a sustained basis. Furthermore, 80 percent of the areas in Gujarat most vulnerable to drought are not yet connected to the project by the necessary canals, therefore, 90 percent of the water planned for irrigation still flows into the sea.

Concerned that the economic benefits would be small and easily negated by the environmental costs, the World Bank withdrew its funding of the dam some years ago. Ecologists say that far less costly water-management strategies, such as rainwater harvesting, intensified groundwater recharge (artificially assisted replenishment of the aquifer), and watershed management would be better options for the farmers of Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Minister Modi quickly ended his hunger strike when the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the Sardar Sarovar Dam could be raised higher (it now stands at 121.92 meters, or 400 feet). The following day, Medha Patkar ended her fast as well, because in the same decision the Supreme Court ruled that all people displaced by the dam must be adequately relocated. Furthermore, the court decision confirmed that human impact studies are required for all dam projects. Up to then, no such study had been done for the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Nonetheless, by September of 2012, the dam project was 8 years behind schedule and had stalled again in court. Both sides were using the Internet to promote their positions. Meanwhile, Narendra Modi achieved national prominence and in 2013 began a controversial campaign to be re-elected chief minister of Gujarat. [Sources: India eNews; Friends of the River Narmada; Environmental Justice, Issues, Theories, and Policy; and the Wall Street Journal. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

The recent history of water management in the Narmada River valley highlights some key issues now facing South Asia and other regions that have developing economies. Across the world, large, poor populations are depending on increasingly overtaxed environments, and these dependencies and pressures on fragile environments are only increasing with climate change. Improving the standard of living for the poor nearly always requires increases in water and energy use. Misplaced efforts to meet these urgent needs often make neither economic nor environmental sense, but are driven to completion by political and social pressures. In the case of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the wealthier, more numerous, and more politically influential farmers of Gujarat have tipped the scale in favor of a project that may be creating more problems than it is solving.

The role of water in South Asian life, including the ways water use intersects with other central issues, is a recurring topic in this chapter.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Sardar Sarovar Dam and similar dams throughout the world are created primarily for irrigation and power generation, but their side effects often create more problems than they solve.

The Sardar Sarovar Dam and similar dams throughout the world are created primarily for irrigation and power generation, but their side effects often create more problems than they solve. The management of water—whether there is too much of it, too little of it, or where it is unfairly apportioned—has been a feature of South Asian life for a long time. Climate change now makes management more problematic.

The management of water—whether there is too much of it, too little of it, or where it is unfairly apportioned—has been a feature of South Asian life for a long time. Climate change now makes management more problematic. Improving the standard of living of poor populations in many parts of the world nearly always requires increases in water and energy use.

Improving the standard of living of poor populations in many parts of the world nearly always requires increases in water and energy use.