Afghanistan and Pakistan

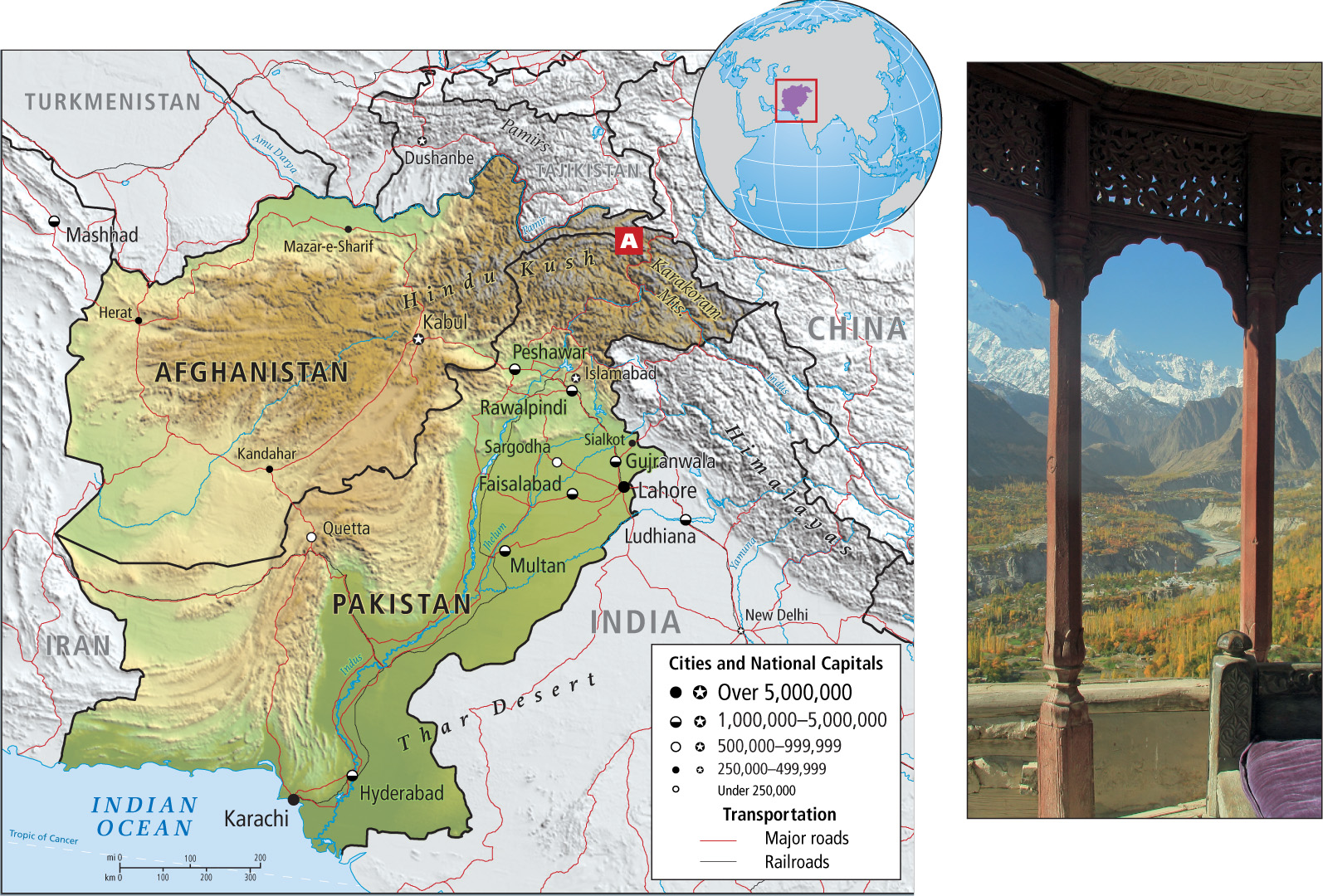

Afghanistan and Pakistan (Figure 8.32) share location, landforms, and history, and they have both been involved in recent political disputes over global terrorism. Historically, many cultural influences have passed through these mountainous countries into the rest of South Asia: Indo-European migrations, Alexander the Great and his soldiers, the continual infusions of Turkic and Persian peoples, and the Turkic-Mongol influences that culminated in the Mughal invasion of the subcontinent at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Today, both countries are primarily Muslim and rural; 77 percent of Afghanistan’s people and 65 percent of Pakistan’s live in villages and hamlets. Nonetheless, each country has some large cities. In Afghanistan, Kabul has several million more inhabitants than its official population estimate of 3 million people; Kandahar has a half million people; and Herat, 400,000. In Pakistan, there are nine cities with more than a million inhabitants, including Karachi (13 million), Lahore (7 million), Faisalabad (2 million), Rawalpindi (2 million), and Peshawar (1.4 million). The capital of Islamabad has 700,000. Both countries must cope with arid environments, scarce resources, and the need to find ways to provide rapidly growing urban and rural populations with higher standards of living. Both countries are home to conservative Islamist movements. Pakistan has a weak elected government that, to stay in power, is dependent on a strong military whose loyalties—to the government or to Islamic fundamentalists—are constantly in question. Afghanistan’s more extreme poverty is made worse by the armed strife under which it has suffered for more than 30 years (see below).

The landscapes of this subregion are best considered in the context of the ongoing tectonic collision between the landmasses of India and Eurasia. At the western end of the Himalayas, the collision uplifted the lofty Hindu Kush, Pamir, and Karakoram mountains of Afghanistan and Pakistan. This system of high mountains and intervening valleys swoops away from the Himalayas and bends down to the southwest and toward the Arabian Sea. Landlocked Afghanistan, bounded by Pakistan on the east and south, Iran on the west, and Central Asia on the north, is entirely within this mountain system. Pakistan has two contrasting landscapes: the north, west, and southwest are in the mountain and upland zone just described; the central and southeastern sections are arid lowlands watered by the Indus River and its tributaries. In both countries, earthquakes regularly occur due to tectonic compression and active mountain building.

Afghanistan

The Hindu Kush and the Pamirs in the northeast of Afghanistan are rugged and steep-sided (see Figure 8.32). The mountains extend west, then fan out into lower mountains and hills, and eventually into plains to the north, west, and south. In these gentler but still arid landscapes, characterized by rough, sparsely vegetated meadows and pasturelands, most in the country struggle to earn a subsistence living from cultivation and the keeping of grazing animals. Rural people remain seminomadic, moving in order to locate forage and water resources for their animals (Figure 8.33). The main food crops are wheat, fruit, and nuts. Opium poppies are native to this region, but they were not an important modern cash crop until the Soviet invasion in 1979; the ensuing wars created the environment for opium production and profits.

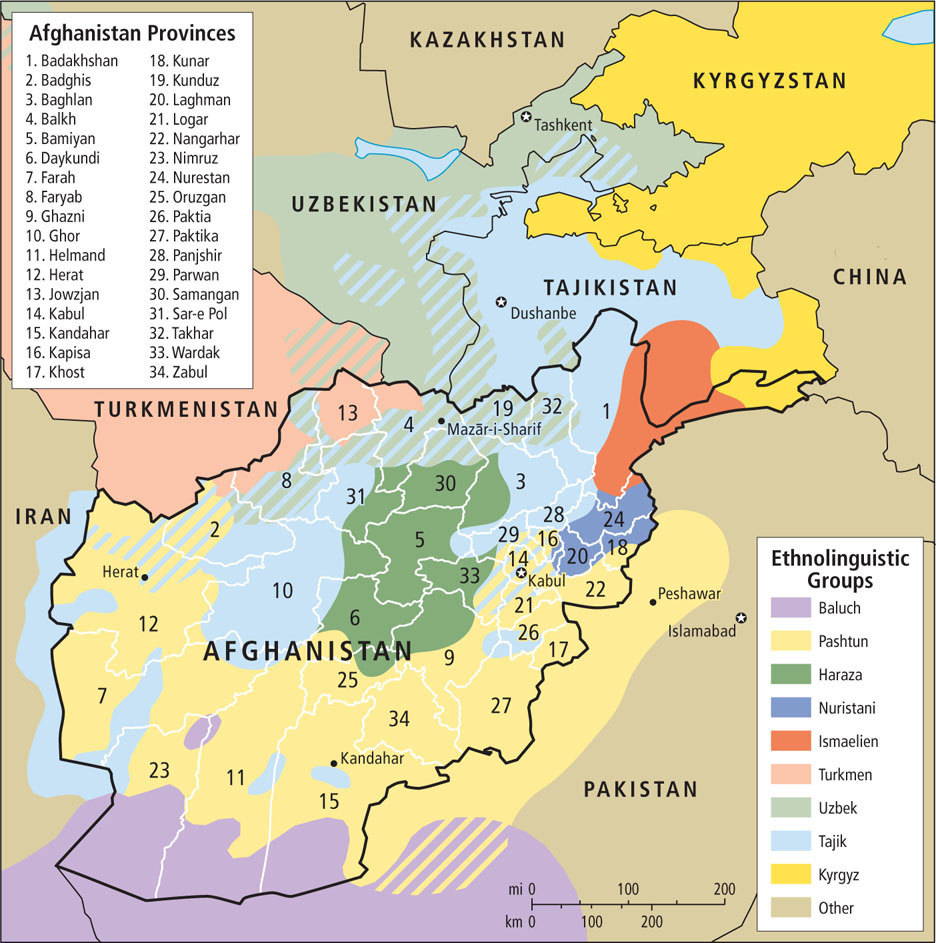

The less mountainous regions in the north, west, and south are associated with Afghanistan’s main ethnic divisions. Very few of these groups could properly be called tribes. Rather, they are ancient ethnic groups. In the north along the Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan borders are the Afghan Turkmen, Uzbek, and Tajik ethnic groups, who share cultural and language traditions with the people of these three countries and are intermingled with them (Figure 8.34). The Hazara, who are concentrated in the middle of the country, trace their biological ancestry to the Mongolian invasions of the past, yet today are closely aligned with Iranian culture and languages. In the south, the Pashto-speaking Pashtuns and Baluchis are culturally akin to groups farther south across the Pakistan border. There is significant variation within each group, especially regarding views on religion, education, modernization, and gender roles. For example, the Taliban are primarily illiterate Pashtuns. On the other hand, educated Pashtuns, long important in Afghan governance, played an important role in the resistance against the Taliban, and many are strong advocates of women’s rights and a democratic and corruption-free Afghan government.

Afghanistan has just 33.4 million people (2012), but its rate of increase is the fastest in the region (2.8 percent per year). Women have 6.2 children, on average (see Figure 8.25); as mentioned above, literacy rates are exceedingly low for men and women. The ethnic diversity of Afghanistan and its neighbors has thwarted many efforts to unite the country under one government (see Figure 8.34). Although the various ethnic groups have remained separate and competitive, contrary to Western media reports, they have not been at continuous war with one another. However, the events of the last several decades in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of 1979 (see the discussion) have disturbed long-standing relationships and feelings of trust. More important, the sheer devastation of almost three decades of war has left Afghanistan crippled. Although the traditional rural subsistence economy proved remarkably resilient in the face of ongoing civil strife, the self-sufficiency of that system has been compromised by an ongoing drought.

The cities of Afghanistan contrast with the countryside and with one another. Back in the 1970s, the capital Kabul was a modernizing city with utilities and urban services, tree-lined avenues and parks, and lifestyles similar to those in cities elsewhere in South Asia. Most women were not veiled; girls attended schools and wore the latest fashions. Then the Russians invaded and brought to Kabul a version of Western culture that quickly alienated the more conservative countryside. Alcohol consumption and partying were common, Russian women dressed scantily and provocatively, respect for religious piety was nil, and all this became negatively associated in Afghan minds with modernization. After the mujahedeen defeated the Russians and the Taliban came to power, modernization became anathema. Kabul suffered destruction first as the Russians were driven out and then as the Taliban were themselves driven out in 2001. Today, Kabul officially has 3 million people but probably actually has several million more. The built environment is much diminished by war. The cities of Herat in the west and Kandahar in the south were always more traditional and culturally conservative—more in tune with the hinterlands. Both were devastated during the late-twentieth-century conflicts, and little rebuilding has taken place in either city in recent years.

Pakistan

Although not much larger in area than Afghanistan, Pakistan has more than five times as many people (180.4 million). Pakistanis, too, live primarily in villages (65 percent), though the country has many large cities. Some villages sprinkled throughout the arid mountain districts are associated with herding and subsistence agriculture, but it is the lowlands that have attracted the most settlement. Here, the ebb and flow of the Indus River and its tributaries during the wet and dry seasons form the rhythm of agricultural life. The river brings fertilizing silt during floods and provides water to irrigate millions of cultivated acres during the dry season.

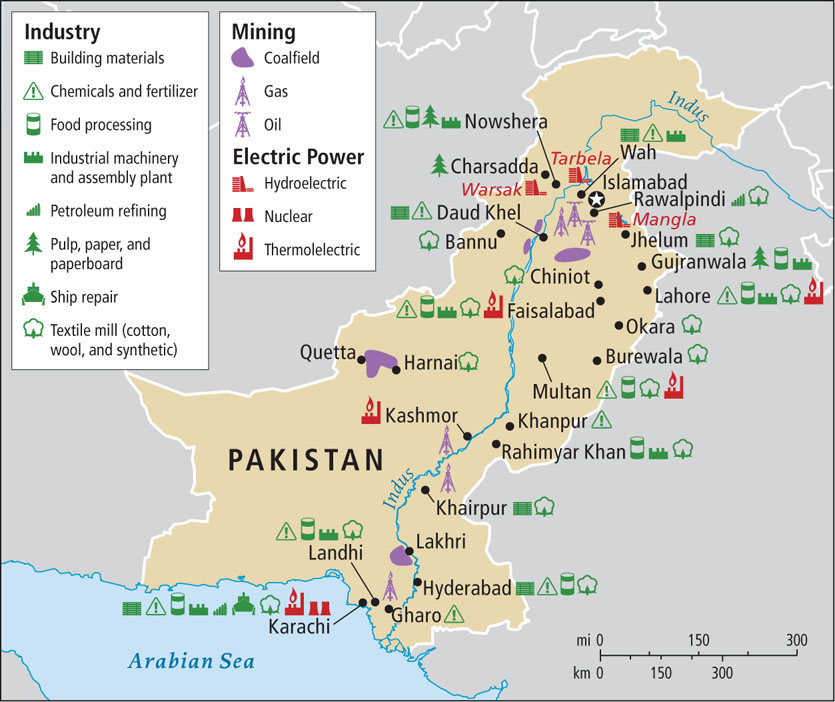

From the 1980s to 2007, Pakistan had a favorable annual economic growth rate of 6 percent or better. In 2009, that rate fell to just 2.7 percent because of the global recession and persistent civil disruptions linked to Al Qaeda and the war in Afghanistan. Agriculture in the Indus River basin, especially in the Pakistani Punjab, used to be a primary economic sector. Cash crops such as cotton, wheat, rice, and sugarcane were grown in large irrigated fields, as they had been for many thousands of years. Recent irrigation projects, however, have overstressed the system, resulting in waterlogged and salinized soil. As a result, the contribution of agriculture to GDP has shrunk in recent years, with industry and services taking over, in part. Although textile, yarn-making, and embroidery industries are growing around the cities of Lahore and Karachi, providing jobs for some rural people, the wealth generated has not resulted in higher wages or local investment, but rather has gone into the pockets of the wealthy, who invest outside of Pakistan. There are exceptions: Pakistan has a host of well-educated writers who inform the English-speaking world about sociopolitical relations in their country. Some land-owning elites invest selflessly in their constituents. An example is the Aga Khan, a member of the hereditary upper class in the Hunza Valley (see Figure 8.32A); his efforts to make public education available for the population have increased literacy to 90 percent.

Pakistan’s northern mountainous hinterlands, where government authority is difficult to establish, have become a major home base for Al Qaeda. The country has a particularly problematic and ineffective military, a fragile and dysfunctional political system that stifles dissent, and a nuclear arsenal. These realities have made Pakistan even more worrisome to the West than is Afghanistan. Public opinion among the masses (who have an overall literacy rate of just 54 percent, with the rate for females only 39 percent) is starkly anti-Western; but it also does not favor rule by Islamic militants.

196. NEW PAKISTANI GOVERNMENT TRIES TALKING PEACE WITH TALIBAN MILITANTS

196. NEW PAKISTANI GOVERNMENT TRIES TALKING PEACE WITH TALIBAN MILITANTS

197. PAKISTAN OPINION POLL SAYS MAJORITY DOES NOT SUPPORT ISLAMIST MILITANTS

197. PAKISTAN OPINION POLL SAYS MAJORITY DOES NOT SUPPORT ISLAMIST MILITANTS

In many ways, Pakistan’s difficulties of today are the outcome of Cold War geopolitics, when antidemocratic and militaristic regimes were propped up and heavily armed by the West to gain strategic advantage over the USSR. During this time, Pakistan was able to surreptitiously acquire nuclear capabilities and sell nuclear secrets to Iran, Libya, and North Korea. Billions of dollars of Western aid went to support the Pakistani military, and while too little went to the people for education and social reforms or to strengthen democratic institutions, there was an effort to create an economy that could provide jobs for young adults in government and commerce. Figure 8.35 is a 2012 map that shows a variety of centers of economic activity in Pakistan (compare this with the topographic map of Pakistan in Figure 8.32).

Frequent terrorist bombings show the power of Islamic militants to disrupt Pakistan’s economy and society (and that of Pakistan’s neighbors; see the discussion of the Mumbai attacks). In an effort to calm the situation, in 2012 the U.S. Congress approved an assistance bill to provide U.S.$1.5 billion to strengthen Pakistan’s legislative and judicial systems; buttress health care; and improve the public education system, with a special emphasis on classes for women and girls. Many Pakistanis worry that this social aid is merely intended to Westernize them. Meanwhile, educated elites struggle to come to terms with their own privilege, Westernized ways, and impotence in the face of terrorism.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Both Afghanistan and Pakistan have high mountains in the north that are the result of the ongoing tectonic collision between the landmasses of India and Eurasia. Both countries have arid lowlands to the south and west; the Indus River and its tributaries water those in Pakistan, but Afghanistan has fewer sources of water.

Both Afghanistan and Pakistan have high mountains in the north that are the result of the ongoing tectonic collision between the landmasses of India and Eurasia. Both countries have arid lowlands to the south and west; the Indus River and its tributaries water those in Pakistan, but Afghanistan has fewer sources of water. Inefficient, corrupt governments plague both countries, and both have predominately conservative, fiercely independent rural populations with diverse ethnic backgrounds. Islamic fundamentalism appeals to many in both countries, especially in rural areas.

Inefficient, corrupt governments plague both countries, and both have predominately conservative, fiercely independent rural populations with diverse ethnic backgrounds. Islamic fundamentalism appeals to many in both countries, especially in rural areas.