Himalayan Country

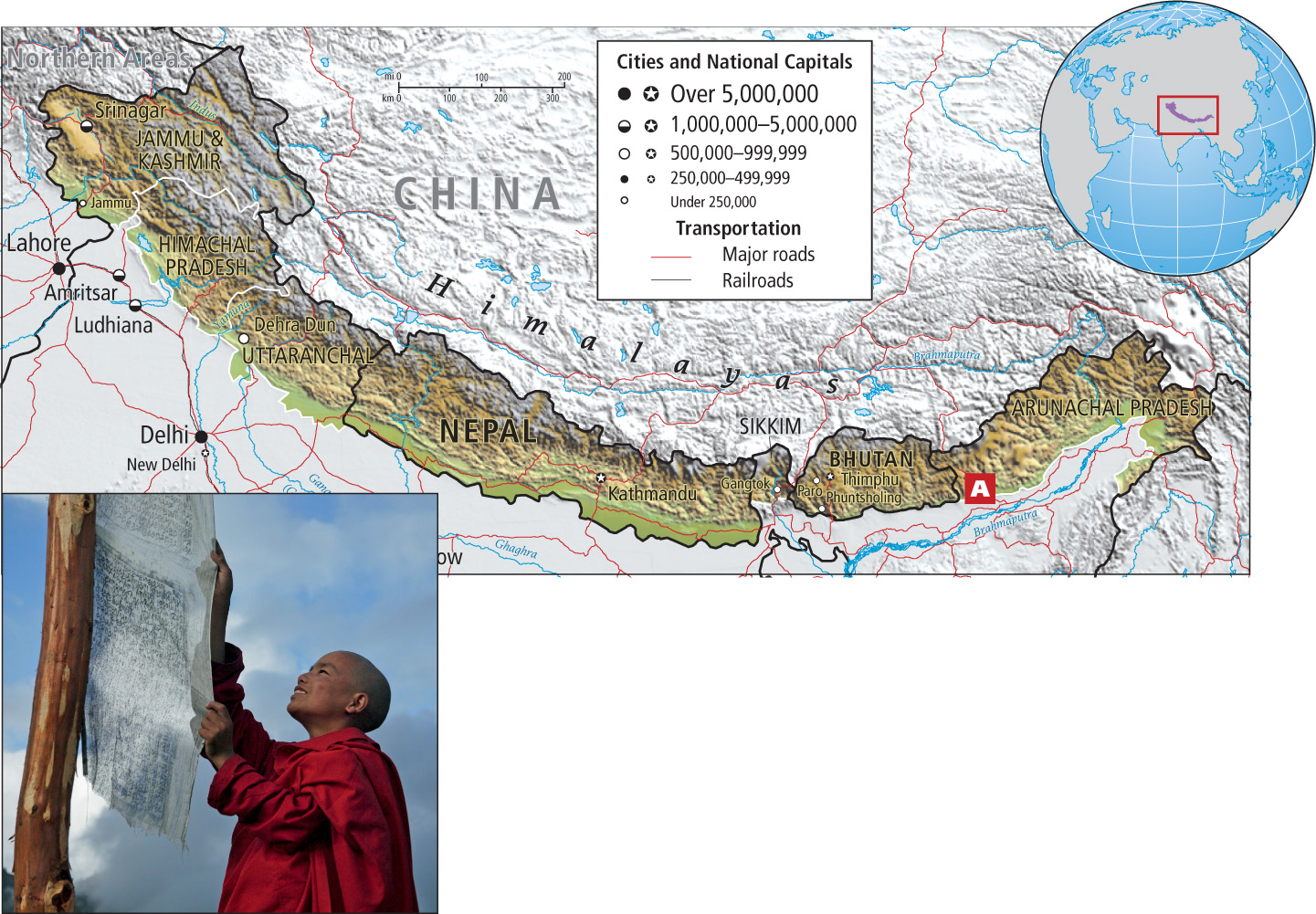

The Himalayas form the northern border of South Asia (Figure 8.36). This subregion is constructed of the mountainous portions of the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttaranchal, and Arunachal Pradesh, and the countries of Nepal and Bhutan. Notice that the country of India has a far eastern lobe that borders Myanmar (Burma). Physically, this mostly mountainous subregion grades from relatively wet in the east to dry in the west because the main monsoons move up the Bay of Bengal and deposit the heaviest rainfall there before moving north and west (see Figure 8.4 and Figure 8.1).

This strip of Himalayan territory can be viewed as having three zones: (1) the high Himalayas, (2) the foothills and lower mountains to the south, and (3) a narrow strip of southern lowlands along the base of the mountains. This band of lowlands forms the northern fringe of the Indo-Gangetic Plain in the west and the narrow Assam Valley of the Brahmaputra River in the east. Although some people manage to live in the high Himalayas, most people live in the foothills, where they cultivate strips and terraces of land in the valleys or herd sheep and cattle on the hills. Some of this area is extremely rural in character—for example, Bhutan’s capital city, Thimphu, with just 98,000 inhabitants, is the largest town in that country; many towns have 2000 or fewer people. The capital of Nepal is Kathmandu, a rapidly urbanizing city that (with its suburbs) has about 1.5 million people.

Culturally, the Himalayan Country subregion is Muslim in the west and Hindu and Buddhist in the middle; animist beliefs are important throughout but are especially strong in the far eastern portion. Throughout the subregion, but especially in valleys in the high mountains and foothills, indigenous people continue to live in traditional ways, isolated from daily contact with the broader culture. In the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, for instance, at the eastern end of the subregion, a population of less than 1 million speaks more than 50 languages.

Despite cultural differences, the Himalayan people have learned to survive in their difficult mountain habitat by relying on one another. An example of this cross-cultural reciprocity comes from central Nepal, where two indigenous groups engage in a complicated seasonal cycle of trade that links them with both Tibet to the north and India to the south.

VIGNETTE

The Dolpo-pa people are yak herders and caravan traders who live in the high, arid part of Nepal where they can produce only enough barley and corn to feed themselves for half the year. Through trade, they parley that half-year supply of grain into enough food for a whole year.

At the end of the summer harvest, they load some of their grain onto yaks and head north to Tibet, where they trade grain to Tibetan nomads in return for salt, a commodity in short supply in Nepal. They keep some salt for their own use and carry the rest to the Rong-pa people in the central foothills of Nepal, where they exchange the salt for sufficient grain to last through the winter. The Rong-pa live in a zone where they cultivate wheat and beans but also herd sheep and goats, and salt is a necessary nutrient for them and their animals. If the Dolpo-pa do not bring enough salt to meet all the Rong-pa needs, the Rong-pa load some goats and sheep with bags of red beans and set out for Bhotechaur in western Nepal, where they meet Indian traders at a bazaar. They trade their beans for iodized Indian salt, sell a sheep or two, and buy some cloth and perhaps a copper pan to take home. [Source: Eric Valli and the movie Himalaya. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Most people in the Himalayan subregion are very poor. Statistics for the Indian states in this subregion hover near those for Nepal, which has an annual per capita GNI of just U.S.$1200, adjusted for PPP. In Nepal, the average life expectancy is 68, literacy is about 60 percent (48 percent for women), and nearly half of the children under 5 years of age are malnourished. At present, only 18 percent of the land is cultivated, and the country’s high altitude and convoluted topography make agricultural expansion unlikely. The government’s strategy, therefore, is to improve crop productivity and lower the population growth rate (now 1.8 percent per year).

Bhutan, with a GNI per capita that is roughly four times that of Nepal, is still far from rich. The country is reliant on agriculture in difficult mountainous environments and on trade of mostly cottage industry products with India, which also extends various types of aid to Bhutan for infrastructure development. Bhutan has become famous for its positive view of life and was the first country to promote the idea of measuring human well-being with a “gross national happiness” quotient (see Figure 8.36A). It now promotes this concept to environmentally and spiritually conscious tourists who pay a fee of $250 a day to visit the country. Bhutan is also known for being the last place on Earth to get television and the Internet, which happened only in the last several years. A 10-minute video that shows the effect of TV on Bhutan society can be found at http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/bhutan/.  194. BHUTAN STRIVES TO DEVELOP “GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS”

194. BHUTAN STRIVES TO DEVELOP “GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS”

The Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, at the far eastern end of the Himalayan subregion, is one of the more lightly populated and environmentally rich areas of the subregion. Moist air flowing north from the Bay of Bengal brings plentiful rain as it lifts over the mountains. This is one of the most pristine regions in India. Forest cover is abundant, and a dazzling sequence of flora and fauna occupies habitats at descending elevations: glacial terrain, alpine meadows, subtropical mountain forests, and fertile floodplains. Conditions at different altitudes are so good for cultivation that lemons, oranges, cherries, peaches, and a variety of crops native to South America—pineapples, papayas, guavas, beans, corn (maize), and potatoes—are now grown commercially for shipment to upscale specialty stores, primarily in India.

Over the past 20 years, the Himalayan Country subregion has undergone numerous changes brought about by the increasing numbers of tourists trekking and climbing the mountains and seeking spiritual enlightenment at its numerous holy sites. Tourism, in particular, has been a mixed blessing, creating economic opportunities for some but also having a transforming effect on the culture and the landscape.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

In this mountainous subregion, there are a variety of cultures and belief systems among relatively sparse populations.

In this mountainous subregion, there are a variety of cultures and belief systems among relatively sparse populations. Many people use multiple livelihood strategies and reciprocal trade to survive, generally making do with little.

Many people use multiple livelihood strategies and reciprocal trade to survive, generally making do with little. With the possible exception of Arunachal Pradesh, the physical environment of this subregion precludes much expansion into agriculture or industry.

With the possible exception of Arunachal Pradesh, the physical environment of this subregion precludes much expansion into agriculture or industry.