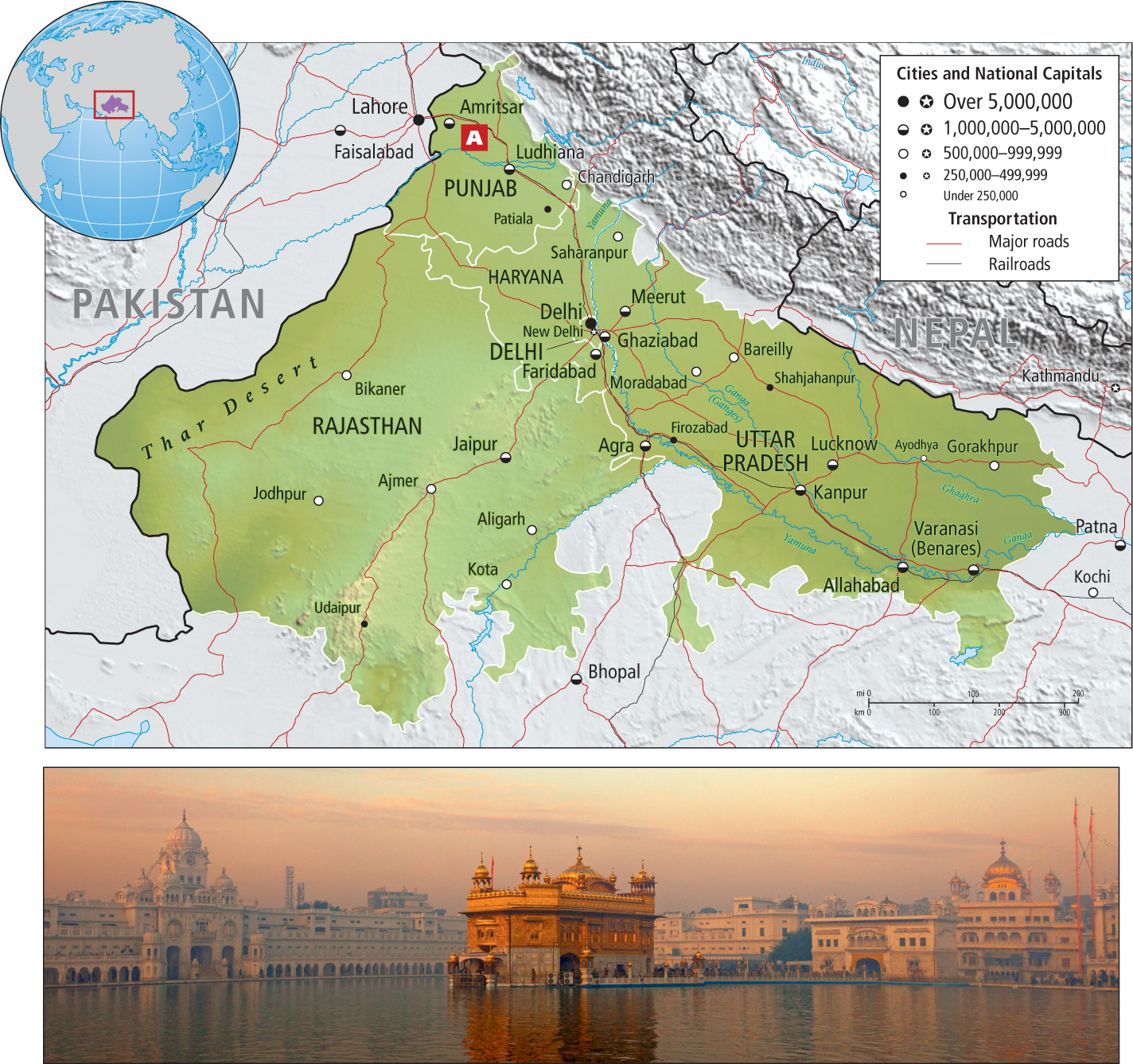

Northwest India

Northwest India stretches almost a thousand miles from the states of Punjab and Rajasthan at the border with Pakistan, eastward to encompass the famous Hindu holy city of Varanasi (Figure 8.37). It is dry country, yet it contains some of the wealthiest and most fertile areas in India.

In the western part of this subregion, so little rain falls that houses can safely be made of mud and have flat roofs. Widely spaced cedars and oaks are the only trees, and the landscape has a dusty khaki color. Villagers plow the landscape between the trees using oxen and a humpbacked breed of cattle called Brahman, and then plant crops of barley and wheat, potatoes, and sugarcane. Along the northern reaches of the subregion, the rivers descending from the Himalayas compensate for the lack of rainfall. The most important is the Ganga, which, with its many tributaries, flows east and waters the state of Uttar Pradesh, bringing not only moisture but also fresh silt from the mountains.

The western half of the Northwest India subregion contains one of India’s poorest states—Rajasthan—as well as one of its wealthiest—the Indian part of Punjab, where the Sikhs have their holiest site (see Figure 8.37A). Rajasthan, with only a few fertile valleys, is dominated by the Thar Desert in the west, which covers more than a third of the state. Historically, small kingdoms (Rajasthan means “land of kings”) were established wherever water could be contained. Seminomadic herders of goats and camels still cross the desert with their animals, selling animal dung or trading it for grazing rights as they travel, thus keeping farmers’ fields fertile and their fires burning. Perhaps the best-known seminomads are the Rabari, about 250,000 strong today. Since the 1990s, however, more and more small farmers have occupied former pasturelands. Although these farmers still want dung for their fields, they cannot afford to lose one bit of greenery to passing herds, so the increasing population pressure means that the benefits of reciprocity between herders and farmers are being lost.

In arid Rajasthan, less than 1 percent of the land is arable, but agriculture, poor as it is, produces 50 percent of the state’s GDP. It is not surprising that the average annual per capita GDP (PPP) is just U.S.$2093 (see Figure 8.30). The crops include rice, barley, wheat, oilseeds, peas and beans, cotton, and tobacco. A thriving tourist industry, focused on the palaces and fortresses constructed by Hindu warrior princes of the past who fought off invaders from Central Asia, accounts for much of the other half of the GDP.

Unlike Rajasthan, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh receive water and fresh silt carried down from the mountains by rivers. Nearly 85 percent of Punjab’s land is cultivated, and in some years Punjab alone provides nearly two-thirds of India’s food reserves. The typical crops are corn, potatoes, sugarcane, peas and beans, onions, and mustard. Punjab’s productive agriculture contributes to its high average annual per capita GDP (PPP) of about U.S.$4300, more than double that of Rajasthan. These differences in wealth result partly from differences in physical geography, from the introduction of green revolution technology, and from the growing influence of the global economy and associated urbanization.

Although agriculture is the most important economic activity throughout the subregion and employs about 75 percent of the people, well-paying jobs are generated by industry in and around the city of Delhi in Uttar Pradesh and on the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Here, as elsewhere in the subregion, typical industries are sugar refining and food processing, as well as the manufacture of cotton cloth and yarn, cement, glass, and steel. Residents also make craft items and hand-knotted wool carpets.

The city of New Delhi, India’s capital, is located approximately in the center of Northwest India. The British built the city center in 1931 just south of the old city of Delhi—an important Mughal city—amid the remains of seven ancient cities. It has all the monumental hallmarks of an imperial capital, and all the problems one might expect of a big city where so many are poor. The Delhi metropolitan area (including the old and new cities and outlying suburbs) has more than 19.5 million people and attracts a continuing stream of migrants. Most have left nearby states to escape conflict or poverty, or both, such as those who have fled Tibet to escape Chinese oppression and others who have fled the conflicts with Pakistan since the 1980s. Annual per capita GDP (PPP) in Delhi (U.S.$5887) is above the average for India (U.S.$3468), but actual incomes for most people are far lower because Delhi’s tiny minority of the extremely wealthy pulls up the average. Delhi’s rather high literacy rate (82 percent), while already15 percent higher than the country’s rate, is held down by the continual arrival of migrants from poor, rural areas. In fact, Delhi has far fewer schools than it needs for its population because jobs increasingly require a high level of skills, not mere literacy. Because of its rapid growth, the city has difficulty providing even the most basic services; water, power, and sewer facilities are insufficient, and 75 percent of the city structures violate local building standards. Many people have no buildings to inhabit at all; they live in shanties constructed from found materials.

In 2011, Delhi was found to have worse pollution than Beijing, China. Delhi is landlocked and frequently experiences cold air inversions, which hold the polluted air low over the city. The metropolitan area has an annual pollution-related death toll of 7500. Most of the pollution comes from the more than 3 million unregulated motor vehicles: taxis, trucks, buses, motorized rickshaws, and scooters—most without pollution control devices, and all competing for space, cargo, and passengers. Because the external air pollution is so intractable, firms dealing in devices to clean interior air abound in New Delhi.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Agriculture is the economic base of the region, employing some 75 percent of the population; however, industrial enterprises are increasing around Delhi and along the Ganga Plain.

Agriculture is the economic base of the region, employing some 75 percent of the population; however, industrial enterprises are increasing around Delhi and along the Ganga Plain. The Northeast India subregion is home to New Delhi, India’s capital that is host to a never-ending migration of people seeking jobs and education. Pollution is one of the many side effects of rapid growth and modernization.

The Northeast India subregion is home to New Delhi, India’s capital that is host to a never-ending migration of people seeking jobs and education. Pollution is one of the many side effects of rapid growth and modernization.