Northeastern South Asia

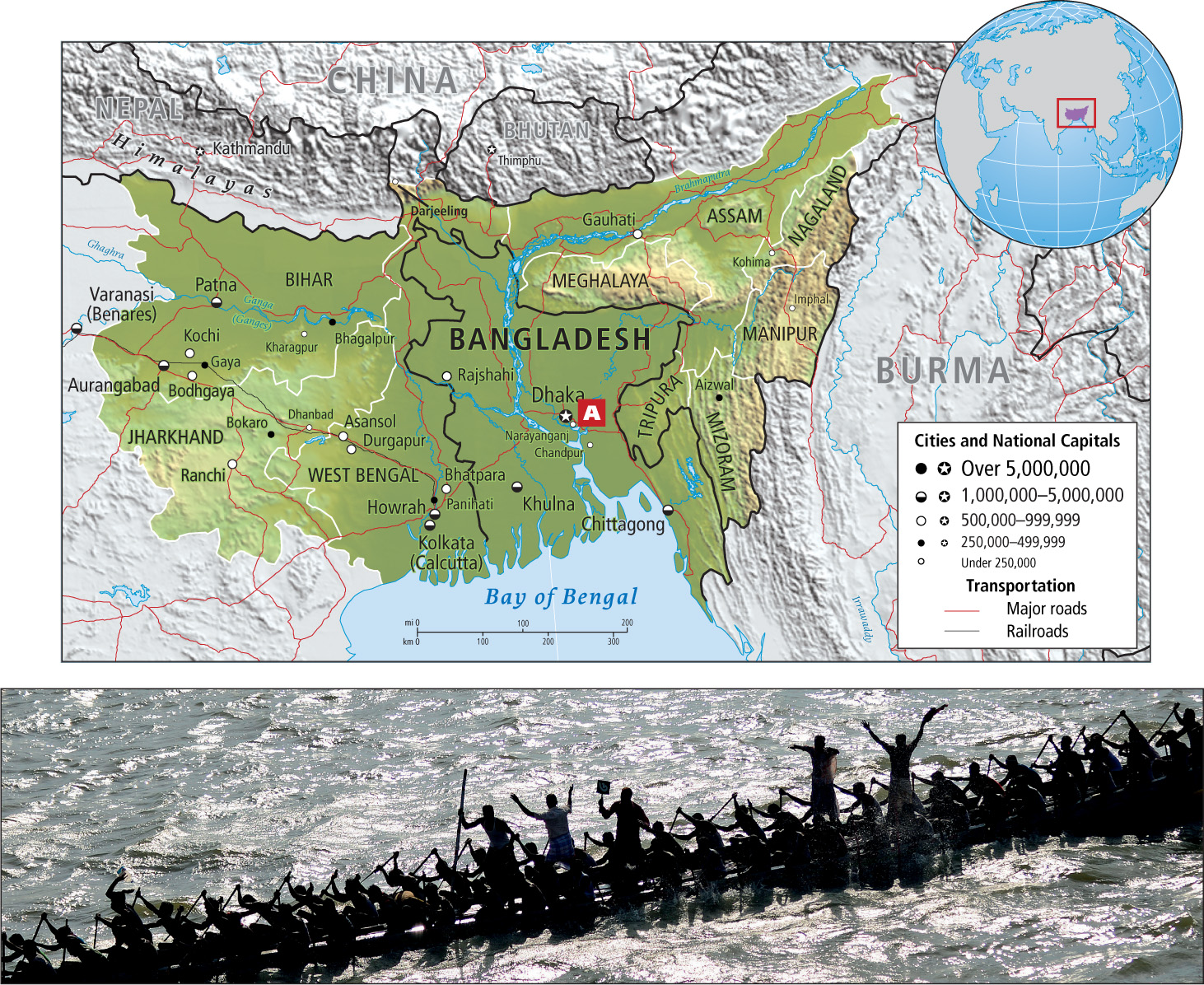

Northeastern South Asia, in strong contrast to Northwest India, has a wet, tropical climate. This subregion bridges national and state boundaries, encompassing the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal in India; the country of Bangladesh; and the far eastern Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura—all clustered at the north end of the Bay of Bengal (Figure 8.38). This area is viewed as a subregion because of its dominant physical and human features. The Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers and the giant drainage basin and delta region created by those rivers as well as the wet climate and fertile land have nourished a population that is now among the most densely populated in the world (see the Figure 8.24 map). Here, we discuss several parts of the Indian portion of this subregion before moving on to Bangladesh.

The Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta

The largest delta on Earth is that formed by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers. Every year, the two rivers deposit enormous quantities of silt, building up the delta so that it extends farther and farther out into the Bay of Bengal. The rivulets of the delta change course repeatedly, and then periodically the bay is flushed out by a huge tropical cyclone (see Figure 8.6). The people of the delta have learned never to regard their land as permanent, and they have adapted their dwellings, means of transportation (see Figure 8.38A), and livelihoods to the drastic seasonal changes in water level and shifting deposits of silt. Villages sit on river terraces or, in the lowlands, are raised on stilts above the high-water line. Moving about in small boats, people fish during the wet season, but when the land emerges from the floods, they return to farming. Called nodi bhanga lok (“people of the broken river”), those who occupy the constantly shifting silt of the delta region are looked down upon by more permanent settlers on slightly higher ground. Because they must often flee rising floodwaters, they are less secure financially and are thought by their neighbors to lack the qualities of thrift and good citizenship that come from living in one place for a lifetime. Currently, their livelihoods (and at times their very lives) are threatened by periodic cyclones and climate change–related sea level rise, compounded by the loss of nourishing sediment caused by river diversions upstream.

West Bengal

With a population of 80 million packed into an area slightly larger than Maine, West Bengal is India’s most densely occupied state (see Figure 8.24). Refugees have dramatically increased the population of West Bengal, which has taken in people from eastern Bengal (now part of Bangladesh) after Partition in 1947; migrants fleeing the Pakistani civil war (1971) that gave Bangladesh its independence; and the Tibetan refugees of the Chinese takeover of Tibet (1979). Today, better employment and farming opportunities draw a continual flow of Bangladeshi migrants (most of them migrating illegally) across the border into India. The result is a mix of cultures that are frequently at odds; often Hindus and Muslims demonstrate and dispute with indigenous people over land occupied by new migrants.

Nearly 75 percent of the people in this crowded state earn a living in agriculture, but agriculture accounts for only 35 percent of West Bengal’s GDP. In addition to growing food for their own consumption, many people work as rice and jute cultivators or as tea pickers—all labor-intensive but low-paying jobs. Twenty-five percent of India’s tea comes from West Bengal; the plant is grown in the far north of the state around Darjeeling, a name well known to tea drinkers. One consequence of the dense population’s dependence on agriculture is that the land has become overstressed and soil fertility has declined. In addition, impoverished farm laborers who must gather firewood because they cannot afford other fuels deplete the surrounding woodlands.

Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta), a giant, vibrant city of 16 million people, is famous in the West for Mother Teresa’s ministrations to its poor at Nirmal Hriday (Home for Dying Destitutes). Bengalis, however, are also proud of their two native Nobel laureates—Rabindranath Tagore (literature) and Amartya Sen (economics)—and of their Academy Award–winning filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who received a lifetime achievement Oscar.

Kolkata was built on a swampy riverbank in 1690 and served as the first capital of British India. But its sumptuous colonial environment has become lost in the squatters’ settlements that have invaded the city’s parks and boulevards and periphery. The city’s decline began in the late 1940s, when Partition and agricultural collapse sent millions of people pouring into Kolkata and other cities. Soon the crowds overwhelmed the city’s housing and transportation facilities. Outmoded regulations limited incentives to start businesses and to improve private property. In the late 1990s, the physical decline, economic inertia, and lack of opportunity in Kolkata sent young professionals fleeing to other parts of the world.

By 2005, however, those who had fled Kolkata were returning to partake in an economic revival, based primarily on technology industries, and new graduates were staying. Unfortunately, old Kolkata is not being refurbished; rather, developers are building new, exclusive gated suburbs on the wetlands south of the city (in areas exposed to future sea level rise). At least 50 large construction projects are underway (though progress slowed during the recession which began there in 2007); they are expected to eventually attract another 7 or 8 million people to this lowland metropolitan area. Thus far, those worrying about the fate of old Kolkata, or about the environmental ramifications of such massive building on wetlands within the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta, are not getting much coverage in the press.

Far Eastern India

Far Eastern India has two physically distinct regions: the river valley of the Brahmaputra where the river descends from the Himalayas, and the mountainous uplands stretching south and east of the river between Burma on the east and Bangladesh on the west (see the Figure 8.38 map). Although migrants have recently arrived here from across South Asia, ancient indigenous groups that are related to the hill people of Burma, Tibet, and China have traditionally occupied Far Eastern India.

The Indian state of Assam encompasses the Brahmaputra River valley, eastern India’s most populated and most productive area. Hindu Assamese make up two-thirds of the population of 29 million, and indigenous Tibeto-Burmese ethnic groups make up another 16 percent; the rest of the people are recent migrants. The Indian government has attempted to reduce the proportion and influence of the Assamese people (who have continually objected to being under Indian control) by making large tracts of land available to outsiders, such as Bengali Muslim refugees, Nepalese dairy herders, and Sikh merchants. Since the late 1970s, mortal disputes have occurred between the Assamese and the new settlers and between Assam and India’s national government.

More than half the people in Assam work in agriculture; another 10 percent are employed in the tea industry and in forestry (forests cover about 25 percent of the land area, and bamboo, a new flooring product in America and Europe, is a major forest export). Tea is the main cash crop—Assam produces half of India’s tea. Assam also has oil; by the 1990s, Assam’s oil and natural gas accounted for more than half that produced in all of India. Given the country’s shortage of energy, this alone could explain India’s efforts to dominate the Assamese politically.

Colorful names such as “Land of Jewels” and “Abode of the Clouds” convey the exotic beauty of the emerald valleys, blue lakes, dense forests, carpets of flowers, and undulating azure hills in the mountainous sections of eastern India that surround Assam. In these uplands, occupied largely by indigenous ethnic groups, people produce primarily for their own consumption and devise ingenious ways to make use of local natural resources. The state of Mizoram ranks second in India in literacy (88 percent) due to the influence of Christian missionary schools.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Logistics of Development

Bangladesh’s march toward a better life has not been based on luck, but rather on carrying out interlocking, methodical steps. Publicly funded family planning (birth control) has empowered women to have far fewer babies and to turn their energy toward gaining education for themselves and their children. The boom in textile manufacturing has provided jobs for the literate, and microcredit has put entrepreneurial activities within reach of the ambitious poor. Improved rice varieties have protected against crop failures and famine, and the many Bangladeshi working abroad regularly send remittances to their families. Additionally, the government has maintained social safety net spending for the poorest.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of South Asia’s poorest countries and one of the world’s most densely populated predominantly agricultural nations. More than 153 million people live in an area slightly smaller than Alabama, with 75 percent of them trying to manage as farmers on severely overcrowded land; meanwhile, urban residents struggle with low standards of living in wet environments. The caloric intake for close to one-third of Bangladeshis is insufficient to meet the minimum daily energy requirements, and 40 percent of the children are underweight.

Nevertheless, Bangladesh is making improvements, bit by bit and on many fronts. The percentage of rural people living in poverty is steadily dropping, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development. Adult literacy went from 34 percent in 1990 to 57 percent in 2011, and the enrollment of eligible children in secondary school increased from 30 percent to 45 percent in the same period. Contraceptives have become more available, and 61 percent of women now use some form of birth control, bringing fertility rates down from 7 children per woman in 1974 to 2.3 in 2012. Infant mortality has also dropped, from 128 per 1000 in 1986 to 43 per 1000 in 2012.

Economically, the textile industry (dismantled by the British) is reviving; Bangladesh is now the second-largest exporter of garments after China and has consistently increased its shipments to the U.S. market. Bangladesh bases its competition for market share with India and China by using the high quality of their textiles as a selling point.

Unfortunately, to keep competitive with cheap labor markets throughout Asia, Bangladesh has allowed very relaxed job safety standards, as the disastrous November 2012 factory fire outside Dhaka attests. One hundred and seventeen workers at Tazreen Fashions, reportedly a supplier to Walmart, Sears, the Gap, Disney, Tommy Hilfiger, and other vendors in North America, lost their lives. Tazreen was known to flout safety regulations, and the American importers did not sufficiently oversee the supply chain.

The real hope for economic growth in Bangladesh lies in development from within. The plan is for Bangladeshis to be increasingly able to purchase domestically produced food, textiles, and technology with income from manufacturing jobs and from their own small businesses funded through microcredit. Microcredit is the remarkable innovation of the Grameen Bank that is now jumpstarting entrepreneurial initiatives by the poor worldwide.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Northeastern South Asia clusters around the upper reaches of the Bay of Bengal, home to the world’s largest delta, formed by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers.

Northeastern South Asia clusters around the upper reaches of the Bay of Bengal, home to the world’s largest delta, formed by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers. Climate change puts many lives at risk in Northeastern South Asia, primarily because of water-related impacts. Sea level rise, flooding, and the increased severity of storms imperil many urban and rural residents in the lowland parts of the delta region.

Climate change puts many lives at risk in Northeastern South Asia, primarily because of water-related impacts. Sea level rise, flooding, and the increased severity of storms imperil many urban and rural residents in the lowland parts of the delta region. West Bengal, India’s most crowded state, is in this subregion; its city of Kolkata has a population of more than 13 million.

West Bengal, India’s most crowded state, is in this subregion; its city of Kolkata has a population of more than 13 million. India’s far eastern states manage their diverse cultures and many indigenous peoples, despite meddling from Delhi.

India’s far eastern states manage their diverse cultures and many indigenous peoples, despite meddling from Delhi. Bangladesh, once noted for its poverty and dependence, is using multiple strategies to become economically self-sustaining.

Bangladesh, once noted for its poverty and dependence, is using multiple strategies to become economically self-sustaining.