Southern South Asia

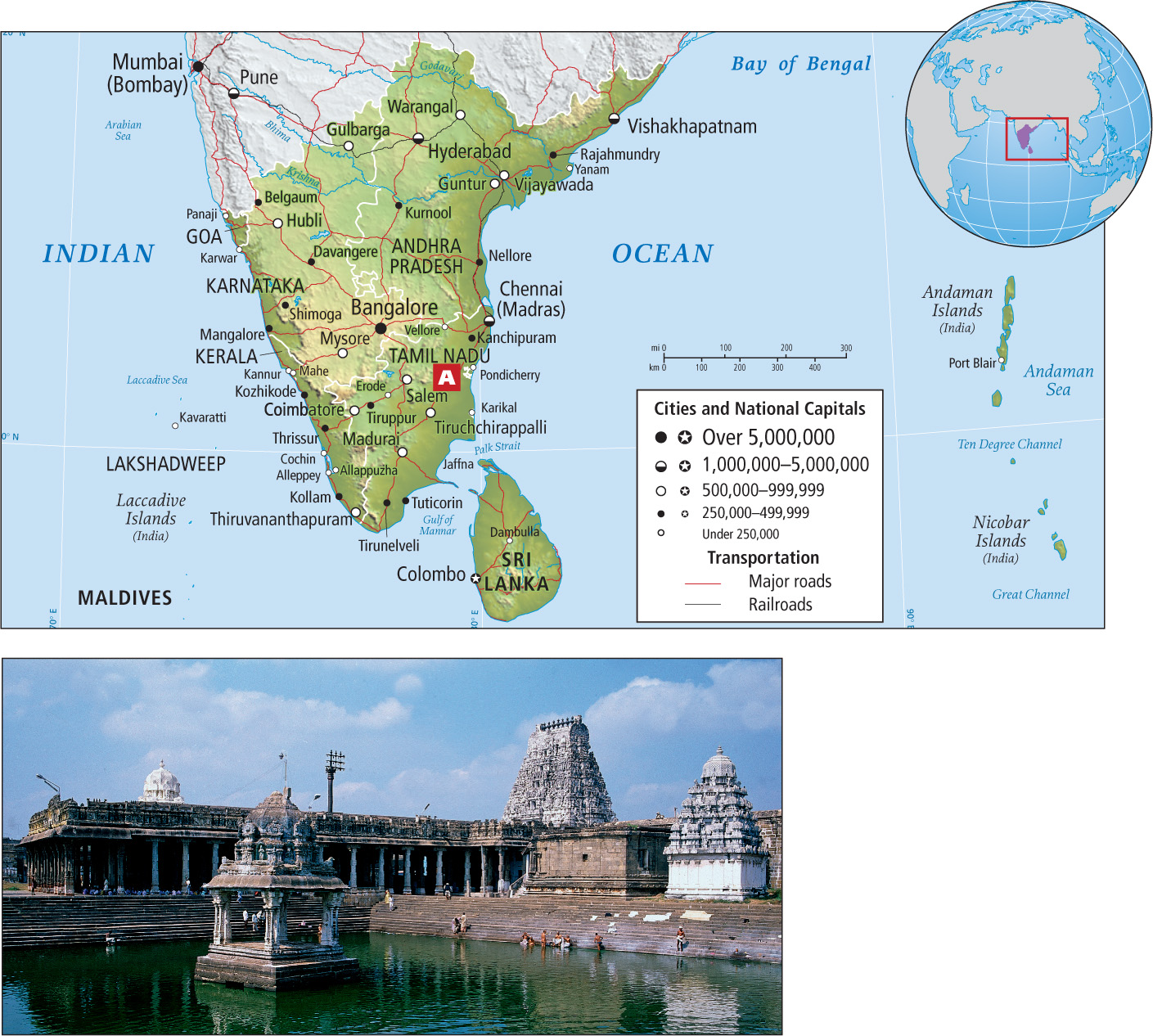

Southern South Asia encompasses the southernmost part of India and the country of Sri Lanka (Figure 8.41). It resembles the rest of the region in that the majority of people—from about 70 percent in the west to somewhat more than 50 percent in the east—work in agriculture. But this subregion is set apart by its relatively high proportion of well-educated people, its advanced technology sector in Bangalore, the strong tradition of elected communist state governments in Kerala, where social services are particularly strong, its focus on environmental rehabilitation and preservation, and the overall higher status and well-being of women. The cultural mix here also sets it apart; it is the center of Dravidian cultures and languages that previously extended into north-central India.

This part of India normally receives consistent rainfall and is well suited for growing rice, peanuts, chili peppers, limes, cotton, cinnamon and cloves, and castor oil plants (used in medicines). The southwestern coast of India (known as the Malabar Coast) has a narrow coastal plain backed by the Western Ghats. The sea-facing slopes of these mountains are some of the wettest in India; they support forests containing teak, rosewood, and sandalwood, all highly valued furniture woods. Small parts of the Deccan Plateau, a series of uplands to the east, are also forested. Here, dry deciduous forests yield teak, tree-farmed eucalyptus, cashews, and bamboo. Several large rivers and numerous tributaries flow eastward across this plateau and form rich deltas along the lengthy and fertile coastal plain facing the Bay of Bengal.

Anomalies in weather patterns are always a possibility. In 2009 this region suffered first an unusual drought during the monsoon season, particularly in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, and then a period of sudden rains. The dried-out soil could not absorb the rain quickly enough, leading to flooding that killed hundreds and ruined crops that had managed to weather the drought. India’s central government was able to provide emergency assistance and food. State governors also planned to import food to keep food prices from rising drastically.

Bangalore and Chennai

Bangalore, long known for its strong information technology (IT) activity, which has drawn thousands of well-trained technical employees from all over India, continues to evolve. It now has many IT rivals throughout South Asia, but remains competitive. Meanwhile, manufacturing has gained markedly; the products produced in and around the city range from appliances and home furnishings to solar-powered lighting and pharmaceuticals. Chennai, 200 miles (320 kilometers) to the east on the Bay of Bengal, is known for its innovative engineering and sustainable development research institutes and is cultivating a role as a prime destination for jobs outsourced from Europe. It now also emphasizes manufacturing and is becoming a center for Italian-designed high-fashion shoe manufacturing. Because styles for these high-end shoes change so rapidly, the Chennai factories are assured of the continuous production of about 2 million pairs per year.

Kerala

Kerala, a primarily coastal state in far southwestern India, is the exception that proves the rule. It is often cited as an aberration in South Asia because gender discrimination is far less prevalent and its people enjoy a higher standard of well-being than the rest of the region. Just why Kerala stands out in this way is not entirely understood, but the state has a unique history. Since the 1950s, it has had a series of elected communist governments that have strongly supported broad-based social services, especially education for both males and females (see Figure 8.21). In addition, it has long had a variation on the traditional family structure that gives considerable power to women; for example, a husband often resides with his wife’s family (a pattern also found in Southeast Asia) instead of the reverse. Female seclusion is less stringently practiced; women are often seen in public, and it is not unusual to see a woman going about her shopping duties alone. Agriculture employs less than half the population of 33.3 million people. Remittances from migrants to the Middle East figure prominently in the state’s economy, and fishing is an important economic sector as well.

Another feature that may have added to the openness of society and greater freedom for women is Kerala’s significant contact with the outside world. Beginning thousands of years ago, traders from around the Indian Ocean, and especially Southeast Asia, made calls along the Malabar Coast, possibly bringing new ideas about gender roles. In the first century c.e., the apostle Thomas is said to have come to spread Christianity (20 percent of Kerala is Christian). Over time, Muslim and Jewish traders brought their faiths by sea as well (25 percent of Kerala is Muslim). Then, between 1405 and 1433, the Chinese explorer General Zheng visited Cochin and the Malabar coast repeatedly. This history of cultural and religious variety seems to have led to more open-mindedness toward diversity than there is in neighboring states.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, known as Ceylon until 1972, is an island country off India’s southeastern coast known for its beauty. From the coastal plains, covered with rice paddies and nut and spice trees, the land rises to hills where tea and coconut plantations are common. At the center is a mountain massif that reaches to nearly 8200 feet (2500 meters) in elevation. The summer monsoons bring abundant moisture to the mountains, giving rise to lush forests and several unnavigable rivers that produce hydroelectric power. Close to 30 percent of the land is cultivated, and just over 25 percent remains forested.

The original hunter-gatherers and rice cultivators of Sri Lanka, today known as Veddas, now number fewer than 5000. Several thousand years ago, settlers from northern India, who built numerous city-kingdoms, joined them. Known as Singhalese, these descendants of northern Indians now constitute about 74 percent of the population of 20.5 million. The Singhalese brought Buddhism to Sri Lanka, and today 70 percent of Sri Lankans (primarily Singhalese) are Buddhists (Figure 8.42).

About a thousand years ago, Dravidian people from southern India, known as Tamils, began migrating to Sri Lanka; by the thirteenth century they had established a Hindu kingdom in the northern part of the island. Later, in the nineteenth century, the British imported large numbers of poor Tamils from the state of Tamil Nadu in southeastern India to work on British-managed tea, coffee, and rubber plantations. Known as “Indian Tamils,” the plantation-based Tamils share linguistic and religious traditions with the “Sri Lankan Tamils” of the north and east, but each community considers itself distinct because of its divergent historical, political, economic, and social experiences. While some Sri Lankan Tamils dominate the commercial sectors of the economy, the Indian Tamils have remained isolated and poverty-stricken plantation workers.

The Sri Lankan civil war between the Singhalese urban majority and the Tamil minority was discussed earlier (and throughout the chapter), as has Sri Lanka’s strong performance in providing education and social services. Now that peace has prevailed since May 2009, there is widespread hope that the Sri Lankan diversified economy, which has proven remarkably resilient through all of the troubles, will be able to perform well enough to quell with prosperity any further ethnic or religious strife.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Although 50 to 70 percent of the people in Southern South Asia work in agriculture, this subregion is set apart by its relatively high proportion of well-educated people, its advanced technology sectors, its strong tradition of elected communist state governments (primarily in Kerala), its focus on environmental rehabilitation and preservation, and the higher status and well-being of women.

Although 50 to 70 percent of the people in Southern South Asia work in agriculture, this subregion is set apart by its relatively high proportion of well-educated people, its advanced technology sectors, its strong tradition of elected communist state governments (primarily in Kerala), its focus on environmental rehabilitation and preservation, and the higher status and well-being of women. Sri Lanka is emerging from a protracted war between the Singhalese urban majority, who reside in the southern two-thirds of the country, and the Tamil minority, who live in the north.

Sri Lanka is emerging from a protracted war between the Singhalese urban majority, who reside in the southern two-thirds of the country, and the Tamil minority, who live in the north.