Human Patterns over Time

A variety of groups have migrated into South Asia, many of them as invaders who conquered peoples already there. Despite much blending over the millennia, the continued coexistence and interaction of many of these groups make South Asia both a richly diverse and an extremely contentious place.

The Indus Valley Civilization

Indus Valley civilization the first substantial settled agricultural communities, which appeared about 4500 years ago along the Indus River in modern-day Pakistan and northwest India

Harappa culture see Indus Valley civilization

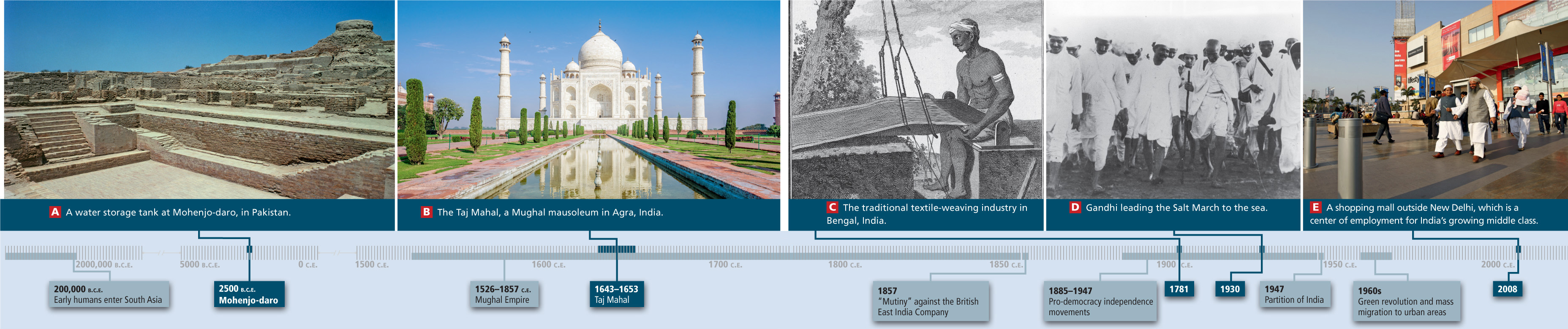

Vestiges of the Indus Valley civilization’s agricultural system survive to this day in parts of the valley, including techniques for storing monsoon rainfall to be used for irrigation in dry times (shown in Figure 8.13A). Remnants of language, and possibly superficial biological traits such as skin color, survive today among the Dravidian peoples of southern India, who originally migrated from the Indus region beginning about 2000 years ago.

The reasons for the onset of the decline of the Indus Valley civilization are debated. Some scholars believe that complex geologic (seismic) and ecological (drier climate) changes brought about a gradual demise. Others argue that foreign invaders brought a swift collapse, instigating out-migration.

A Series of Invasions

The first recorded invaders to join the indigenous people of South Asia came from Central and Southwest Asia into the rich Indus Valley and Punjab about 3500 years ago. Many scholars believe that these people, referred to as Indo-European (a linguistic term), in conjunction with those of the Harappa and other indigenous cultures, instituted some of the early elements of classical Hinduism, the major religion of India today. One of those elements was the still-influential caste system (discussed), which divides society into hereditary hierarchical categories.

Mughals a dynasty of Central Asian origin that ruled India from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century

As Mughal rule declined, a number of regional states and kingdoms rose and competed with one another (Figure 8.10). The absence of one strong power created an opening for yet another invasion. By the late 1700s, several European trading companies were competing to gain a foothold in the region. Of these, Britain’s East India Company was the most successful. By 1857, the East India Company, acting as an extension of the British government, put down a rebellion against European intrusion and became the dominant power in the region.

Globalization and the Legacies of British Colonial Rule

The British controlled most of South Asia from the 1830s through 1947 (Figure 8.11). By making the region part of the British Empire, the British accelerated the process of globalization in South Asia, transforming the region politically, socially, and economically. Even areas not directly ruled by the British felt the influence of their empire. Afghanistan repelled British attempts at military conquest, but the British continued to intervene there, trying to make Afghanistan a “buffer state” between British India and Russia’s expanding empire. Nepal remained only nominally independent during the colonial period, and Bhutan became a protectorate of the British Indian government.

The Deindustrialization of South Asia

As in their other colonies, the British used South Asia’s resources primarily for their own benefit, often with disastrous results for South Asians. One example was the fate of the textile industry in Bengal (modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal).

Bengali weavers, long known for their high-quality muslin cotton cloth, initially benefited from the increased access that traders gave them to overseas markets in Asia, the Americas, and Europe. By 1750, South Asia had an advanced manufacturing economy that produced 12 to 14 times more cotton cloth than Britain alone and more than all of Europe combined. However, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Britain’s own highly mechanized textile industry—based on cotton grown in India, various other colonies, and the American South—developed cheaper cloth that then replaced Bengali muslin. This shift happened first in the British colonies in the Americas, then in Europe, and eventually throughout South Asia. The British textile industry was further aided by the British East India Company, which began severely punishing Bengalis who continued to run their own looms. As a result, the venerable South Asian textile industry survived in only a few places (see Figure 8.13C). As Lord Bentinck, a British colonial official put it, “While the mills of Yorkshire prospered, the bones of Bengali weavers bleached on the plains of India.”

Many people who were pushed out of their traditional livelihood in textile manufacturing were compelled to find work as landless laborers. But rural South Asia already had an abundance of agricultural labor, so many migrated to emerging urban centers. In the 1830s, a drought worsened an already difficult situation, and more than 10 million people starved to death. Throughout the nineteenth century, similar events forced millions of South Asian workers to join a stream of indentured laborers migrating to other British colonies in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, where their descendants are still to be found.

Democratic and Administrative Legacies

Contemporary South Asian governments retain institutions put in place by the British to administer their vast empire. These governments inherited many of the shortcomings of their colonial forebears, such as highly bureaucratic procedures, resistance to change, and a tendency to remain aloof from the people they govern. While the governments have proved functional over time, there have been occasional major civil disturbances in virtually every country. Democratic governments were not instituted on a large scale until the final days of the empire, but since independence in 1947 (see below), people have been able to use the freedoms afforded by democracy to voice their concerns and to make many peaceful transitions of elected governments. Still, the struggle to retain and build democratic institutions continues.

Independence and Partition

The tremendous changes brought by the British inspired many resistance movements among South Asians. Some of these were militant movements intent on pushing the British out by force, such as the unsuccessful rebellion of South Asian soldiers employed by the British East India Company in 1857. Other movements, such as the Indian National Congress (founded in 1885), used political means to agitate for greater democracy, which they saw as the route to South Asian political independence. Although both militant and political actions were brutally repressed, the democracy movements gained worldwide attention and, after decades of struggle, were successful.

Nonviolence as a Political Strategy

civil disobedience protesting of laws or policies by peaceful direct action

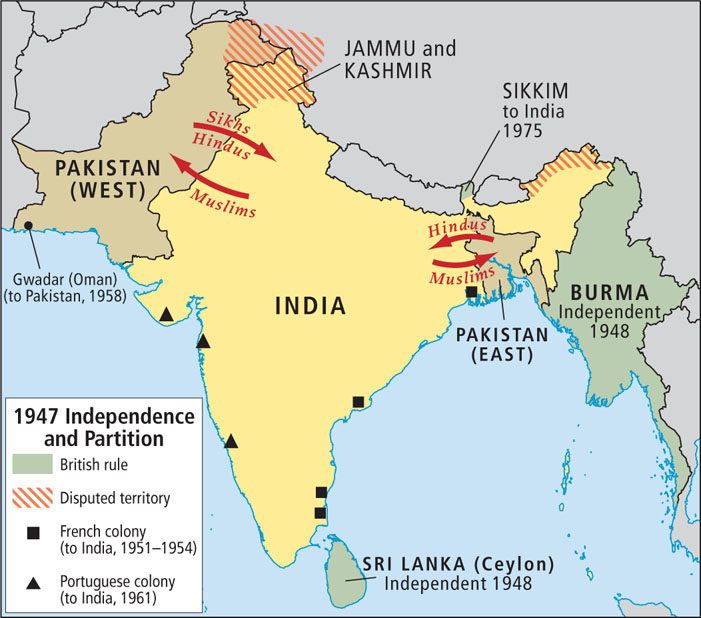

The Partition of India in 1947

Partition the breakup following Indian independence that resulted in the establishment of Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan

Muslim political leaders, concerned about the fate of a minority Muslim population in a united India with a Hindu majority, first suggested the idea of two nations. Though Partition was highly controversial, it became part of the independence agreement between the British and the Indian National Congress (India’s principal nationalist party). Northwestern and northeastern India, two very different places historically and culturally, but where the populations were predominantly Muslim, became a single country consisting of two parts, known as West and East Pakistan, separated by northern India (see Figure 8.12). Although both India and Pakistan maintained secular constitutions, with no official religious affiliation, the general understanding was that Pakistan would have a Muslim majority and India a Hindu majority. Fearing that they would be persecuted if they did not move, more than 7 million Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India from their ancestral homes in what had become West or East Pakistan. A similar number of Muslims left their homes in India for one of the parts of Pakistan. In the process, civil society broke down. Families and communities were divided, looting and rape were widespread, and between 1 and 3.4 million people were killed in numerous local outbreaks of violence. In 1971, after bloody conflict bordering on civil war, Pakistan was divided into Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) and Pakistan (formerly West Pakistan).  184. 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF INDIA–PAKISTAN PARTITION ON AUGUST 15TH

184. 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF INDIA–PAKISTAN PARTITION ON AUGUST 15TH

Partition was the tragic culmination of the divide-and-rule approach the British used throughout their empire (see Chapter 7). The approach heightened tensions between South Asian Muslims and Hindus, thus creating a role for the British as seemingly indispensable and benevolent mediators. Instead of relieving tensions, the partition of India and Pakistan laid the groundwork for the wars and skirmishes, strained relations, and the ongoing arms race between India and Pakistan that persist to this day.

The Post-Independence Period

In the more than 60 years since the departure of the British, South Asians have experienced both progress and setbacks. Democracy has expanded steadily, albeit somewhat slowly. India is now the world’s most populous democracy. It is gradually dismantling age-old traditions that hold back poor, low-caste Hindus, women, and other disadvantaged groups, and a vibrant, if still small, middle class is emerging (see Figure 8.13E). Pakistan has had repeated elections and some of its governments have been modestly effective, but militaristic authoritarian and corrupt regimes have been more the norm, with Pakistan’s and India’s long border feud (discussed) sapping resources and national spirit. Bangladesh, despite the damage it sustained in its war of independence from Pakistan in 1971, has actually had a more stable, responsive, and less militaristic (though not trouble-free) government than Pakistan (see Figure 8.27A, B).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of South Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

This structure was designed to store water from what source?

This structure was designed to store water from what source?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Suggest some principle features of this structure and grounds?

Suggest some principle features of this structure and grounds?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is significant about the fact that as of 1750, before the onset of British colonialism, South Asia produced 12 to 14 times more cotton than Britain and the rest of Europe combined?

What is significant about the fact that as of 1750, before the onset of British colonialism, South Asia produced 12 to 14 times more cotton than Britain and the rest of Europe combined?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What was the immediate result of the Salt March?

What was the immediate result of the Salt March?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What does this photo suggest about Mumbai's economy?

What does this photo suggest about Mumbai's economy?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Under British rule, agricultural modernization lagged, and during World War II, the Bengal Famine took an estimated 4 million lives. After independence, progress in agricultural production was slow until the late 1960s, when the green revolution brought marked improvements. The move to modernized farming on large tracts of land with far fewer agricultural workers brought prosperity to some South Asians, relieved food scarcities, and made food exports possible; but it also forced millions to migrate to the cities. This intensified already vast economic disparities in urban South Asia (see Figures 8.27A, B).

Industrialization became a main goal after independence, partly in response to the dismantling of industry during the colonial period. The emphasis on technical training has produced several generations of highly skilled engineers whose talents are in demand around the world. In most countries in the region, urban-based industrial and service economies now constitute a far larger share of GNI than agriculture (which nonetheless continues to employ 50 percent or more of the workforce). The information technology (IT) sector is growing especially rapidly in India.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Indus Valley/Harappa civilization dating to 4500 years ago is remarkable for its development of many innovations in water management and agriculture.

The Indus Valley/Harappa civilization dating to 4500 years ago is remarkable for its development of many innovations in water management and agriculture. South Asia has been invaded many times, primarily from the north by groups stretching from Greece to Mongolia.

South Asia has been invaded many times, primarily from the north by groups stretching from Greece to Mongolia. Following some 300 years of Mughal rule, the British controlled most of South Asia from the 1830s through 1947, profoundly influencing the region politically, socially, and economically.

Following some 300 years of Mughal rule, the British controlled most of South Asia from the 1830s through 1947, profoundly influencing the region politically, socially, and economically. British colonial rule in South Asia channeled resources to Europe, and in so doing depressed flourishing industries and inhibited development.

British colonial rule in South Asia channeled resources to Europe, and in so doing depressed flourishing industries and inhibited development. In the early twentieth century, Mohandas Gandhi emerged as a central political leader of India’s independence movement, using nonviolent civil disobedience that eventually led to independence.

In the early twentieth century, Mohandas Gandhi emerged as a central political leader of India’s independence movement, using nonviolent civil disobedience that eventually led to independence. Instead of relieving tensions, Partition—the 1947 division of British India into two countries, India and Pakistan—laid the groundwork for the repeated wars and skirmishes, strained relations, and ongoing arms race between India and Pakistan.

Instead of relieving tensions, Partition—the 1947 division of British India into two countries, India and Pakistan—laid the groundwork for the repeated wars and skirmishes, strained relations, and ongoing arms race between India and Pakistan.