Sociocultural Issues

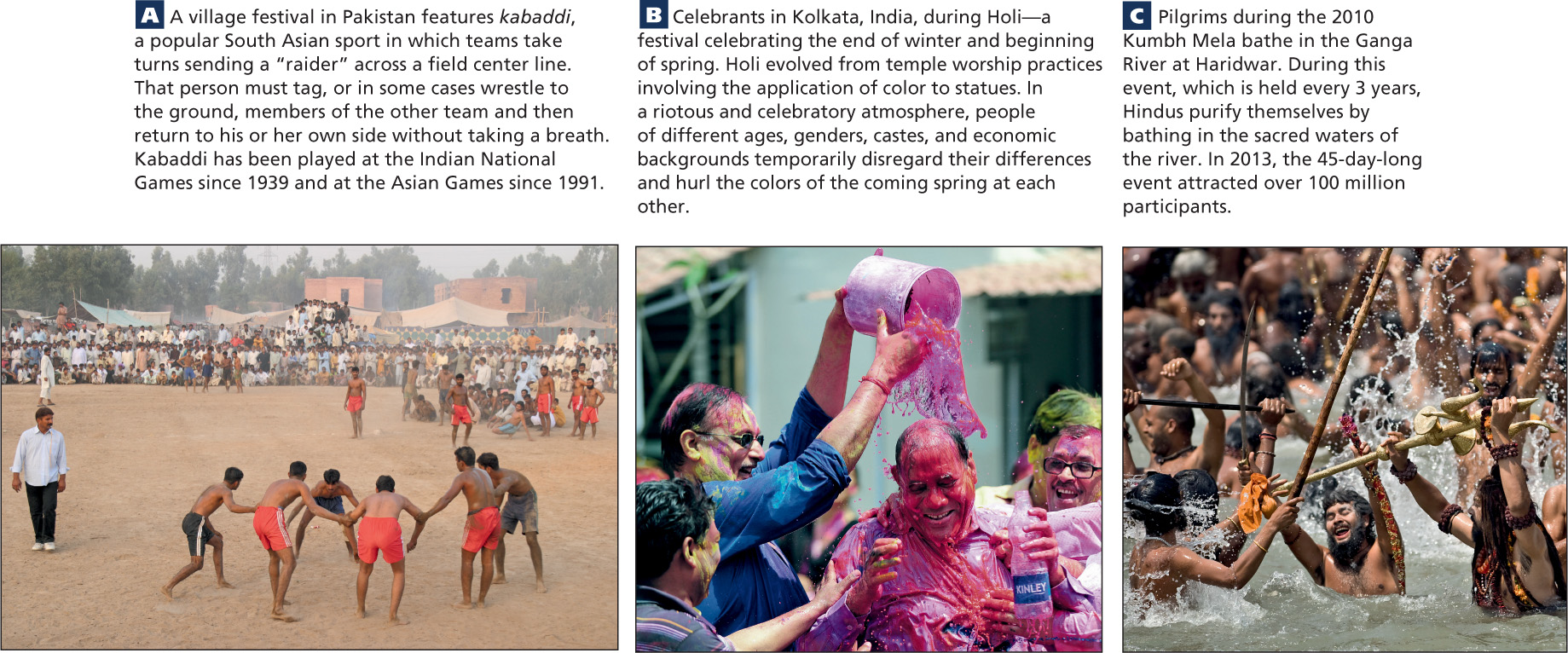

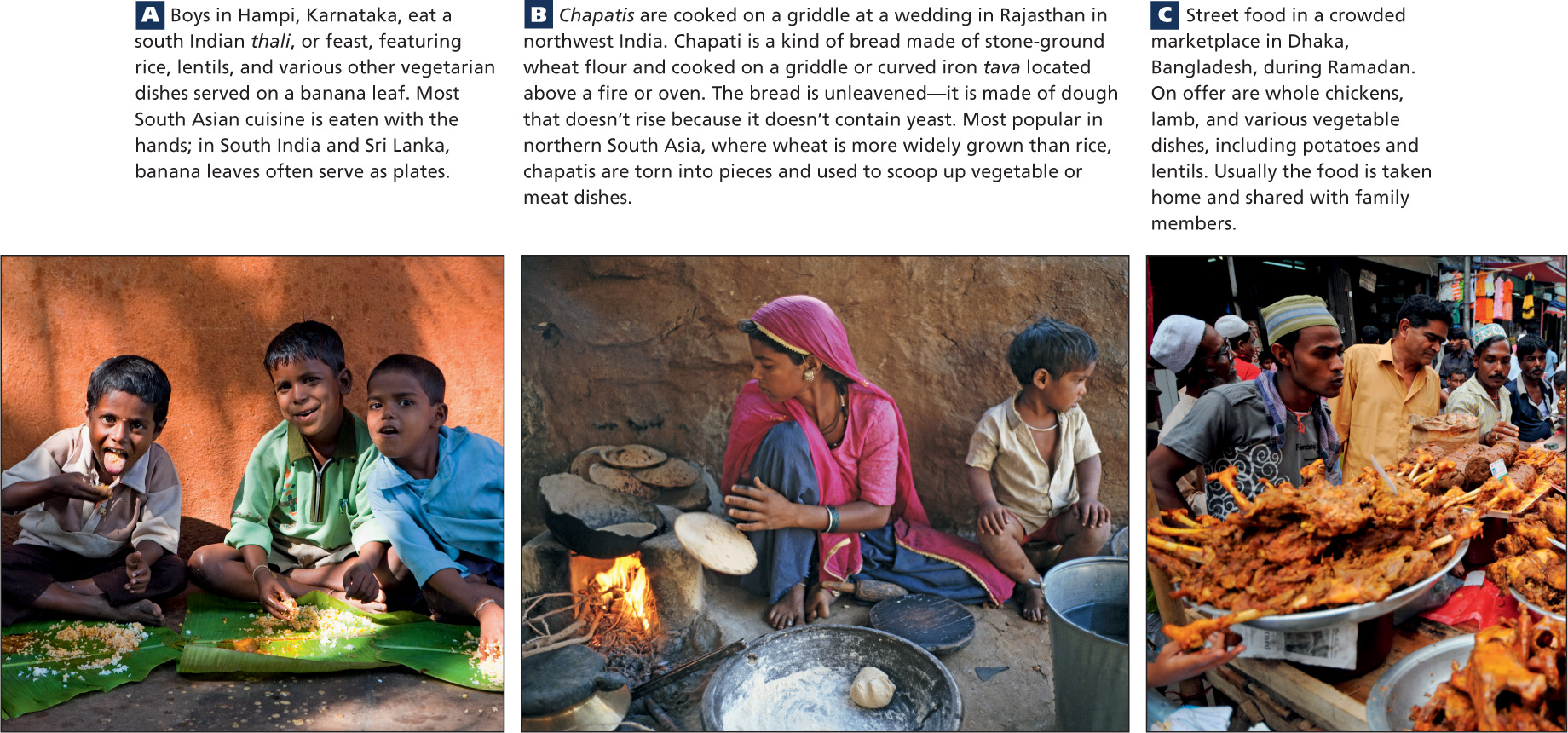

Within the life of one South Asian village or urban neighborhood, there can be considerable cultural variety. Differences based on caste, economic class, ethnic background, gender, religion, and even language are usually accommodated peacefully by long-standing customs, such as religious and ethnic festivals and foodways (Figure 8.14; see also Figure 8.19) that guide cross-cultural interaction. Because of this cultural variety, everyone in South Asia is, in one way or another, a member of a minority. The widespread experience of being part of a minority group is to some extent an equalizing factor and has become part of the national dialogue about difference.

The Texture of Village Life

The vast majority—about 70 percent—of South Asians live in hundreds of thousands of villages. Even many of those now living in South Asia’s giant cities were born in a village or occasionally visit an ancestral rural community, so for most people village life is a lived experience.

VIGNETTE

The writer Richard Critchfield, who studied village life in more than a dozen countries, wrote that the village of Joypur (Bangladesh) in the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta is set in “an unexpectedly beautiful land, with a soft languor and gentle rhythm of its own.” In the heat of the day, the village is sleepy; naked children play in the dust, women meet to talk softly in the seclusion of courtyards, and chickens peck for seeds.

In the early evening, mist rises above the rice paddies and hangs there “like steam over a vat.” It is then that the village comes to life, at least for the men. The men and boys return from the fields, and after a meal in their home courtyards, the men come “to settle in groups before one of the open pavilions in the village center and talk—rich, warm Bengali talk, argumentative and humorous, fervent and excited in gossip, protest, and indignation.” They discuss their crops, an upcoming marriage, or national politics. [Source: Richard Critchfield. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

VIGNETTE

The anthropologist Faith D’Aluisio and her colleague Peter Menzel give another peek into village life as night falls in Ahraura, a village in the state of Uttar Pradesh in north-central India. In the enclosed women’s quarters of a walled compound, Mishri is finishing her day by the dying cooking fire as her 1-year-old son tunnels his way into her sari to nurse himself to sleep. Mishri, who is 27, lives in a tiny world bounded by the walls of the courtyard she shares with her husband, five children, and several of her husband’s kin. Like many villages in northern India, her village observes the practice of purdah, in which women keep themselves apart from men (see the discussion).

That Mishri can observe purdah is a mark of status because it shows she need not help her husband in the fields. Within the compound, she works from sunup to sundown, chatting only momentarily with two women who cover their faces and scurry from their own courtyards to hers for the short visit. Mishri is devoted to her husband, who was chosen for her by her family when she was 10; out of respect, she never says his name aloud. [Source: Adapted from Faith D’Aluisio and Peter Menzel, Women in the Material World, 1996.]

The Texture of City Life

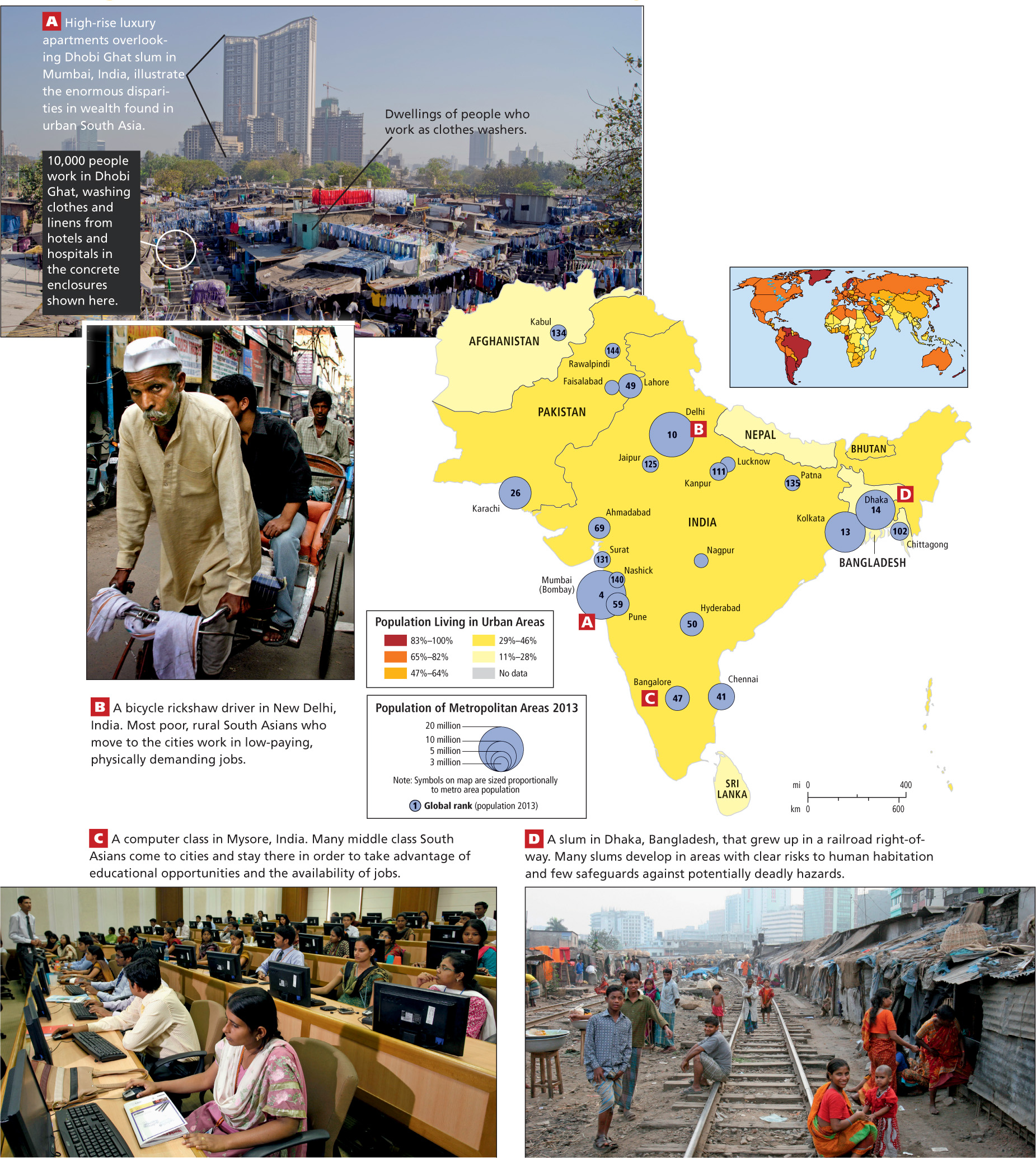

South Asian cities are often depicted as having split identities. On the one hand are sleek, modern skyscrapers bearing the logos of powerful global high-tech firms, and professional workshops filled with bright, motivated students (Figure 8.15C); and on the other hand are chaotic, crowded, and violent urban environments with overstressed infrastructures and menial jobs (see Figure 8.15B, D). Many South Asian cities exemplify this dichotomy; Mumbai is chief among them.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in South Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

(Photos A and D) What circumstances have brought South Asians into the crowded urban districts in these two photos of Mumbai and Dhaka?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is notable about the members of this classroom?

What is notable about the members of this classroom?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Bombay is the name by which most Westerners know South Asia’s wealthiest city. It is now called Mumbai, after the Hindu goddess Mumbadevi. Mumbai has the largest deepwater harbor on India’s west coast. Its metropolitan area, with over 21 million people, hosts India’s largest stock exchange, has multiple IT firms, and is the home of the nation’s central bank. It pays about a third of the taxes collected in the entire country and brings in nearly 40 percent of India’s trade revenue. Its annual per capita GDP is three times that of India’s next wealthiest city, the capital Delhi.

Mumbai’s wealth also extends into the realm of culture through the city’s flourishing creative arts industries, including the internationally known film industry. The industry is known as “Bollywood” because it produces popular Hindi movies portraying love, betrayal, and family conflicts. (The term Bollywood is a combination of Bombay and Hollywood.) The stories, played out on lavish sets and accompanied by popular music and dance, serve to temporarily distract their huge audiences from the physical difficulties of daily life.

When one looks up at the elegant high-rise condominiums built for the city’s rapidly growing middle class, Mumbai’s wealth is most evident. But at street level, the urban landscape is dominated by the large numbers of people living on the sidewalks, in narrow spaces between buildings, and in large, rambling shantytowns (see Figure 8.15A). The largest of the shantytowns is Dharavi, which houses up to a million people in less than 1 square mile. It is said to contain 15,000 one-room factories turning out thousands of products that are sold in the global marketplace, many of them from India’s recycled plastic and metal. Dharavi rivals Orangi Township in Karachi, Pakistan, for the title of one of the world’s most populous slums, but it is also generating future members of the middle class, at least among the factory owners.

There is yet a third aspect to urban life in South Asia. Were one to carefully observe places as widely separated and culturally different as Mumbai, Chennai, Kathmandu, and Peshawar, one would discover that beyond the main avenues and shantytowns, these cities also contain thousands of tightly compacted, reconstituted villages where standards of living are relatively high and daily life is intimate and familiar, not anonymous as in Western cities. Such a place is Koli.

VIGNETTE

Koli is an ancient fishing village that predates the city of Mumbai and is now squeezed between Mumbai’s elegant coastal high-rises and the Bay of Mumbai (Figure 8.16). Some villagers still fish every day. Koli is a labyrinth of low-slung, tightly packed homes ringed by fishing boats. The screeching of taxis and buses is soon lost in quiet calm as one ducks into a narrow covered passageway that winds through the village and branches in multiple directions. At first Koli appears impoverished, but inside, well-appointed homes, some with marble floors, TVs, and computers, open onto the dimly lit but pleasant alleys. The visitor soon learns that this is no warren of destitute shanties, no slum, but rather a community of educated bureaucrats, tradespeople, and artisans who constitute South Asia’s rising urban middle class. [Source: From the field notes of Lydia and Alex Pulsipher and their colleague Tom Osmand].

Although today only 30 percent of the region’s population lives in urban areas, South Asia has several of the world’s largest metropolitan areas. By 2012, Mumbai had 22.9 million people; Kolkata, 16 million; Delhi, 19.5 million; Dhaka, 15.4 million; and Karachi, 11.1 million. All of these cities have grown quickly, and South Asia’s current urban population of about 460 million people could expand to as many as 712 million by 2025.

Many middle-class South Asians move to cities for education, training, or business opportunities (see Figure 8.15C). Because people come to cities where schooling is more available, large cities have higher literacy rates than rural areas. Mumbai and Delhi both have literacy rates above 80 percent, approximately 25 percent above the average for the country; Dhaka, in Bangladesh, and Karachi, in Pakistan, both have 63 percent literacy, more than 15 percent above the rate for each country as a whole.

Like sub-Saharan Africa, the cell phone is bringing urban-style communication into the countryside. Mumbai-based reporter Anand Giridharadas found that over half the population of South Asia now has access to a cell phone. Even though this access is unevenly distributed, for many the cell phone has become a means of creating social privacy and sometimes circumventing social norms. With a cell phone, a person can conduct relationships, keep secrets, access information, and generally undermine the oppression of authority hierarchies. One measure of how rapidly cell phone technology has taken over is that many more South Asians now have a cell phone than have the use of a flush toilet. A result of this rapid change is that the expectations young South Asians have about what the future holds for them are rising briskly, with IT access viewed as essential.

Risks to Children in Urban Settings

In rural areas, by age 5 a child can perform useful tasks, thereby contributing to family well-being. But what about children in urban areas? A report by the International Labor Organization (2008) found that 23 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 are working in South Asia, many of them in urban areas. They work primarily in the informal sector as domestic servants; in export-oriented factories like those small enterprises in urban slums; and as dump scavengers. Some are forced into the sex trade. Clearly, many of these occupations are entirely unsafe and inappropriate for children who should be protected from such exploitation.

But if we look more closely at one occupation that children have, that of carpet weaving, some interesting issues arise. Carpet weaving is an ancient artistic and economic enterprise in South Asia; traditionally, it has been a family-run enterprise, with women and children the weavers and men the merchants. For thousands of years, young children have learned weaving skills from their parents and have become proud members of the family’s home-based production unit. But in today’s rapidly modernizing society, the role of children as family workers must be balanced with the need to have children attend school. One of the chief benefits of urban life is education, where children learn the skills that will enable them to survive and prosper in a modern economy. All citizens need to read, write, and do math.

As global trade has increased the demand for fine, handwoven carpets, most of the profit has gone not to the weaving families but to South Asian middlemen and to foreign traders from Europe and America. The possibility of making large profits has led some unscrupulous carpet merchants to set up factories where kidnapped children are forced to produce carpets. Obviously, kidnapping and enslavement must be stopped, but the question remains: Is there room for cottage industry employment of children within the family circle?

Risks to Women and Men in Urban Settings

When rural adults move to cities, the loss of village constraints on behavior, the need to find a way to make a living, the crowded conditions, the lack of housing, and the welter of new experiences can leave them vulnerable to exploitation and to their own poor judgment.

sex work the provision of sexual acts for a fee

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Can Child Labor Be “Fair Labor”?

The United Nations, South Asian governments, and NGOs like RugMark are now addressing this issue of child labor in the handwoven carpet industry. They have instituted an active program to curb child labor abuses while remaining open to the positive experience for a child of learning a skill and being part of a family production unit. India has established a national system to certify that exported carpets are made in shops where the children go to school, have an adequate midday meal, and receive basic health care. Such carpets bear the label “Kaleen” or “RugMark.”

Brothels are notoriously exploitative of women wherever they are found; but the age of the mobile phone is changing the geography of sex work, at once allowing sex workers to move out of brothels, control those who will become their clients, and manage their incomes, which used to be seized by pimps and madams. However, being spatially autonomous also leaves them less likely to have access to condoms or to learning about how to avoid HIV exposure, for which sex workers are at high risk.

Rural men new to cities are also at risk; on-the-job accidents, exposure to HIV, extreme pressure to support families on tiny wages, and the loss of camaraderie with fellow villagers are but a few of the hardships felt by men.

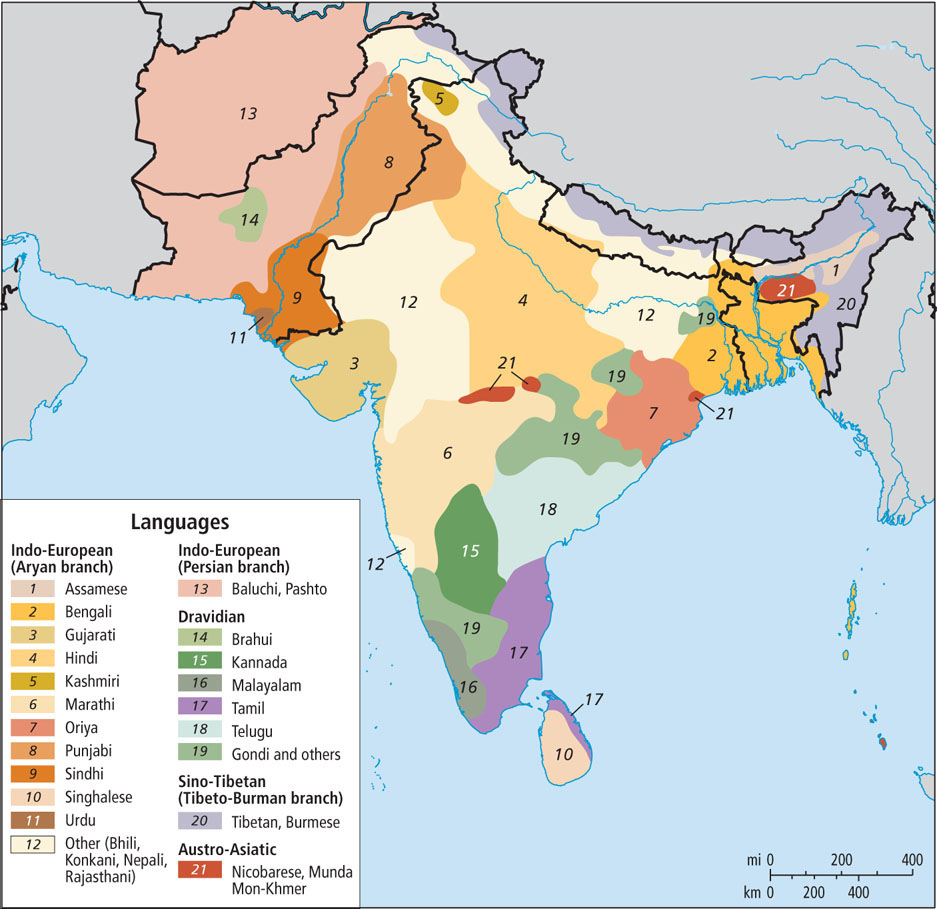

Language and Ethnicity

There are many distinct ethnic groups in South Asia, each with its own language or dialect. In India alone, 18 languages are officially recognized, but there are actually hundreds of distinct languages. This complexity results partly from the region’s history of multiple invasions from outside. However, some groups were isolated for long periods of time, which also contributed to this complexity. As shown in Figure 8.17, the Dravidian language-culture group, represented by numbers 14 through 19, is an ancient group that predates the Indo-European invasions by a thousand years or more. Today, Dravidian languages are found mostly in southern India, but a small remnant of the extensive Dravidian past can still be found in the Indus Valley in south-central Pakistan.

By the time of British colonization, Hindi—an amalgam of Persian-based and Sanskrit-based Indo-European languages—was the dominant language throughout northern India and what is now Pakistan. Today, variants of Hindi serve as national languages for both India and Pakistan (there, called Urdu), though it is the first, or native, language of only a minority. English is a common second language throughout the region. As the language of the colonial bureaucracy, English remains a language used at work by professional people of all categories. Between 10 and 15 percent of South Asians speak, read, and write English. Many others use a version of spoken English.

Religion, Caste, and Conflict

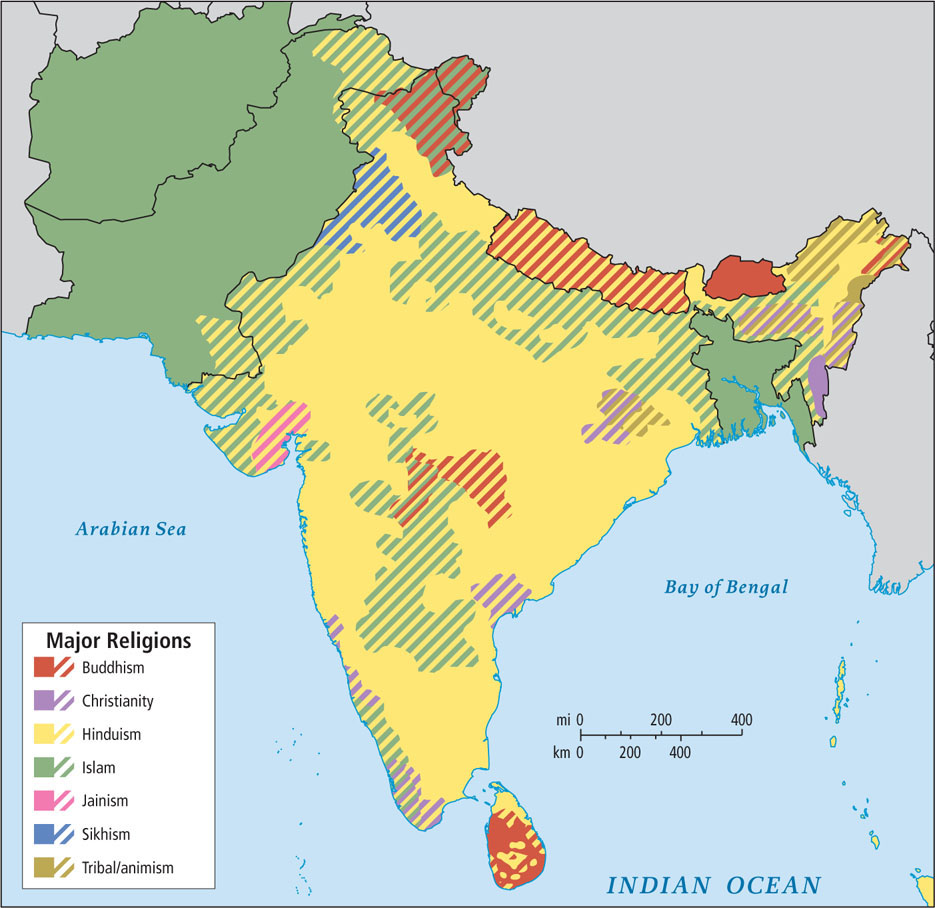

The main religious traditions of South Asia are Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Islam, and Christianity (Figure 8.18). (For a discussion of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, see Chapter 6.)

Hinduism a major world religion practiced by approximately 900 million people, 800 million of whom live in India; a complex belief system, with roots both in ancient literary texts (known as the Great Tradition) and in highly localized folk traditions (known as the Little Tradition)

The Great Tradition is based on 4000-year-old scriptures called the Vedas. Its major tenet is that all gods are merely illusory manifestations of the ultimate divinity, which is formless and infinite. Some devout Hindus worship no gods at all, and instead engage in meditation, yoga, and other spiritual practices designed to bring people to a state described as “infinite consciousness.” The average person, however, is thought to need the help of personified divinities in the form of gods and goddesses (the Little Tradition). While all Hindus recognize some deities (such as Vishnu, Shiva, Ganesh, and Krishna), many deities are found only in one region, one village, or even one family.

Some beliefs are held in common by nearly all Hindus. One is the belief in reincarnation, the idea that any living thing that desires the illusory pleasures (and pains) of life will be reborn after it dies. A reverence for cows, which are seen as only slightly less spiritually advanced than humans, also binds all Hindus together (see Figure 8.9B). This attitude, along with the Hindu prohibition on eating beef, may stem from the fact that cattle have been tremendously valuable in rural economies as the primary source of transport, field labor, dairy products, fertilizer, and fuel (dried animal dung is often burned).

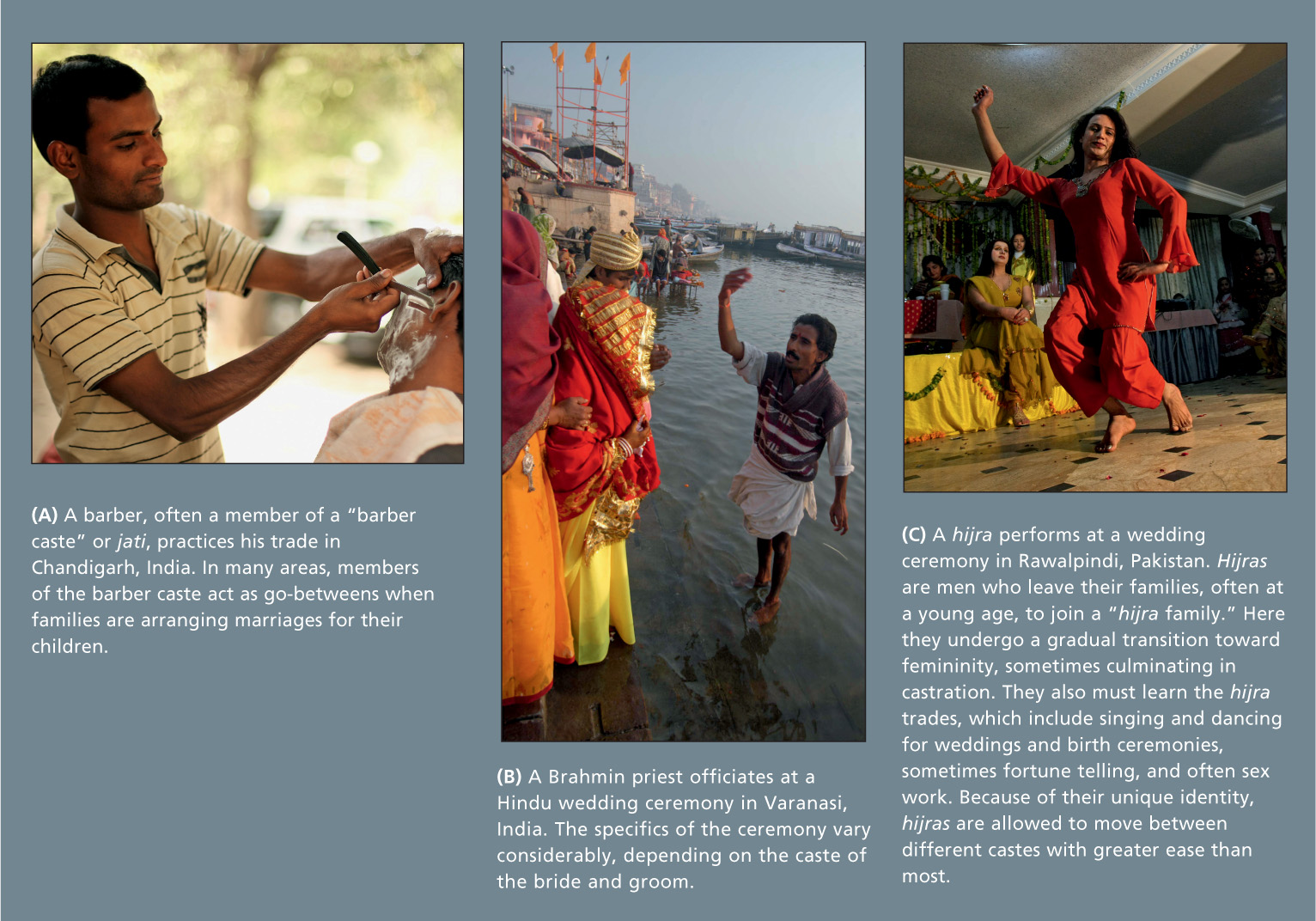

Caste, an Explanation

caste system a complex, ancient Hindu system for dividing society into hereditary hierarchical classes

jati in Hindu India, the subcaste into which a person is born, which traditionally defined the individual’s experience for a lifetime

varna the four hierarchically ordered divisions of society in Hindu India underlying the caste system: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors/kings), Vaishyas (merchants/landowners), and Sudras (laborers/artisans)

Brahmins, members of the priestly caste, are the most advantaged in caste hierarchy. Thus they must conform to those behaviors that are considered most ritually pure (for example, strict vegetarianism and abstention from alcohol). As is the case with many castes, Brahmins are found in many occupations outside their place as priests in the varna system (as barbers and hairdressers, for example). Below Brahmins, in descending rank are Kshatriyas, who are warriors and rulers; Vaishyas, who are land-owning (small-plot) farmers and merchants; and Sudras, who are low-status laborers and artisans. A fifth group, the Dalits—“the oppressed,” or untouchables—is actually considered to be so lowly as to have no caste. Dalits perform those tasks that caste Hindus consider the most despicable and ritually polluting: killing animals, tanning hides, cleaning, and disposing of refuse. A sixth group, also outside the caste system, is the Adivasis, who are thought to be descendants of the region’s ancient aboriginal inhabitants.

Although jatis are associated with specific subcategories of occupations, in modern economies, this aspect of caste is more symbolic than real. Members of a particular jati do, however, follow the same social and cultural customs, dress in a similar manner, speak the same dialect, and tend to live in particular neighborhoods or villages. This spatial separation arises from the higher-caste communities’ fears of ritual pollution, such as through physical contact or the sharing of water or food with lower castes. When one stays in the familiar space of one’s own jati, one is enclosed in a comfortable circle of family and friends that becomes a mutual aid society in times of trouble. The social and spatial cohesion of jatis helps explain the persistence and respect paid to a system that, to outsiders, seems to put a burden of shame and poverty on the lower ranks.

It is important to note that caste and class are not the same thing. Class refers to economic status, and there are class differences within caste groups because of differences in wealth. Historically, upper-caste groups (Brahmins and Kshatriyas) owned or controlled most of the land, and lower-caste groups (Sudras) were the laborers, so caste and class tended to coincide. There were many exceptions, however. Today, as a result of legally mandated expanding educational and economic opportunities, caste and class status are less connected. Some Vaishyas and Sudras have become large landowners and extraordinarily wealthy businesspeople, while some Brahmin families struggle to achieve a middle-class standard of living. By and large, however, Dalits remain very poor.

Caste, Politics, and Culture

In the twentieth century, Mohandas Gandhi began an organized effort to eliminate discrimination against “untouchables.” As a result, India’s constitution bans caste discrimination. However, in recognition that caste is still hugely influential in society, upon independence from Britain, India began an affirmative action program. The program reserves a portion of government jobs, places in higher education, and parliamentary seats for Dalits and Adivasis. Together, the two groups now constitute approximately 23 percent of the Indian population and are guaranteed 22.5 percent of government jobs. Extended in 1990, this program now includes other socially and educationally “backward castes” (the term used in India), such as disadvantaged jatis of the Sudras caste, allotting them an additional 27 percent of government jobs. However, reserving nearly half of government jobs in this way has resulted in considerable controversy. In 2006, medical students successfully protested against quotas in elite higher-education institutions for lower-caste applicants. The Indian Supreme Court ruled in favor of the students.

At the local level, most political parties design their vote-getting strategies to appeal to subcaste loyalties. They often secure the votes of entire jati communities with such political favors as new roads, schools, or development projects. These arrangements fly in the face of the official ideologies of the major political parties and of Indian government policies, which actively work to eliminate discrimination on the basis of caste. Nonetheless, the role of caste in politics seems to be increasing at this time, as several new political parties that explicitly support the interests of low castes have emerged.

Among educated people in urban areas, the campaign to eradicate discrimination on the basis of caste may appear to have succeeded, but the reality is more complex. Throughout the country, there are now some Dalits serving in powerful government positions. Members of high and low castes ride city buses side by side, eat together in restaurants, and attend the same schools and universities. For some urban Indians—especially educated professionals who meet in the workplace—caste is deemphasized as the crucial factor in finding a marriage partner. However, less than 5 percent of marriages cross even jati lines, let alone the broader gulf of varna. Nearly everyone notices the tiny social clues that reveal an individual’s caste, and in rural areas, where the majority of Indians still reside, the divisions of caste remain prevalent.

Geographic Patterns of Religious Beliefs

The geographic pattern of religion in South Asia is complex and overlapping. As Figure 8.18 shows, there is a core Hindu area in central India, with other faiths more common on the fringes of the region.

The approximately 520 million Muslims in South Asia form the majority in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Maldives; and Muslims are a large and important minority in India, where at 140 million, they form about 12 percent of the population. They live mostly in the northwestern and central Ganga River plain.

Buddhism a religion of Asia that originated in India in the sixth century b.c.e. as a reinterpretation of Hinduism; it emphasizes modest living and peaceful self-reflection leading to enlightenment

Jainism a religion of Asia that originated as a reformist movement within Hinduism more than 2000 years ago; Jains are known for their educational achievements, nonviolence, and strict vegetarianism

Sikhism a religion of South Asia that combines beliefs of Islam and Hinduism

The first Christians in the region are thought to have arrived in the far southern Indian state of Kerala with St. Thomas, the Apostle of Jesus, in the first century c.e. Today, Christians and Jews are influential but tiny minorities along the west coast of India. A few Christians live on the Deccan Plateau and in northeastern India near Burma.

Animism, the most ancient religious tradition, is practiced throughout South Asia, especially in central and northeastern India, where there are indigenous people whose occupation of the area is so ancient that they are considered aboriginal inhabitants. (For a discussion of animism, see Chapter 7.)

The Hindu–Muslim Relationship

Indian independence leaders like Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru (first prime minister of India, 1947–1964) emphasized the common cause of throwing off British rule that once united Muslim and Hindu Indians. Since independence, members of the Muslim upper class have been prominent in Indian national government and the military. Muslim generals have served India willingly, even in its wars with Pakistan after Partition. Hindus and Muslims often interact amicably, and they occasionally marry each other. Both groups have influenced the region’s cuisine (Figure 8.19).

communal conflict a euphemism for religiously based violence in South Asia

VIGNETTE

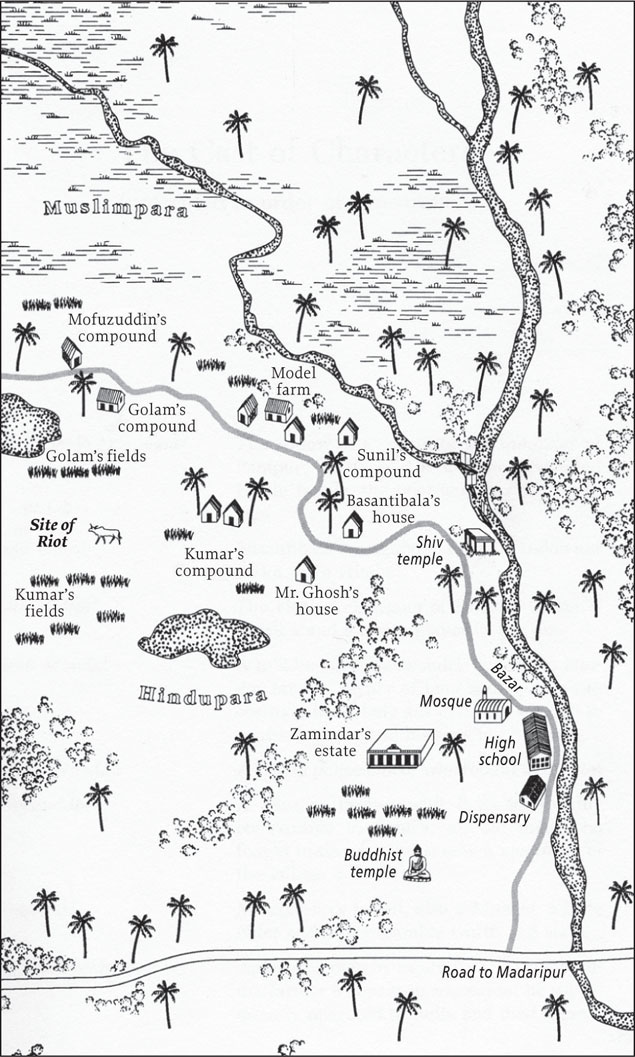

The sociologist Beth Roy, who studies communal conflict in South Asia, recounts an incident that she refers to as “some trouble with cows” in the village of Panipur (a pseudonym) in Bangladesh (Figure 8.20). The incident started when a Muslim farmer either carelessly or provocatively allowed one of his cows to graze in the lentil field of a Hindu. The Hindu complained, and when the Muslim reacted complacently, the Hindu seized the offending cow. By nightfall, Hindus had allied themselves with the lentil farmer and Muslims with the owner of the cow. More Muslims and Hindus converged from the surrounding area, and soon there were thousands of potential combatants lined up facing each other. Fights broke out. The police were called. In the end, a few people died when the police fired into the crowd of rioters. [Source: Beth Roy. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

At the state and national level, Hindu–Muslim conflict has taken on strong political overtones, aspects of which are discussed below under the topic of religious nationalism in the section on political issues.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The cultural, ethnic, religious, and rural/urban variety of life in South Asia means that most everyone is part of a minority group in one way or another, which is to some extent a protection against communal conflict.

The cultural, ethnic, religious, and rural/urban variety of life in South Asia means that most everyone is part of a minority group in one way or another, which is to some extent a protection against communal conflict. Mumbai is South Asia’s wealthiest city and is a showcase of the economic disparity that characterizes South Asian cities.

Mumbai is South Asia’s wealthiest city and is a showcase of the economic disparity that characterizes South Asian cities. Village life is of course a major feature of rural South Asia, but city neighborhoods can share many of the intimate qualities of village life.

Village life is of course a major feature of rural South Asia, but city neighborhoods can share many of the intimate qualities of village life. There are many distinct ethnic groups in South Asia, each with its own language or dialect. Today, variants of Hindi are the principal languages of India and Pakistan, while Bengali is the official language of Bangladesh. English is a common second language throughout South Asia.

There are many distinct ethnic groups in South Asia, each with its own language or dialect. Today, variants of Hindi are the principal languages of India and Pakistan, while Bengali is the official language of Bangladesh. English is a common second language throughout South Asia. Caste and class are not the same thing: “class” refers to economic status, and “caste” to hereditary hierarchical social categories. There are class differences within caste groups because of differences in wealth. Even though India’s constitution bans caste discrimination, caste is still hugely influential in Indian society.

Caste and class are not the same thing: “class” refers to economic status, and “caste” to hereditary hierarchical social categories. There are class differences within caste groups because of differences in wealth. Even though India’s constitution bans caste discrimination, caste is still hugely influential in Indian society. There is a geographic pattern to Hinduism and Islam in South Asia, but it is not absolute and people of different religions often live in close proximity. Relations between Muslims and Hindus can be quite tense, occasionally resulting in violent confrontation. Other religious traditions also play prominent local roles in the life of South Asia.

There is a geographic pattern to Hinduism and Islam in South Asia, but it is not absolute and people of different religions often live in close proximity. Relations between Muslims and Hindus can be quite tense, occasionally resulting in violent confrontation. Other religious traditions also play prominent local roles in the life of South Asia.

Geographic and Social Patterns in the Status of Women

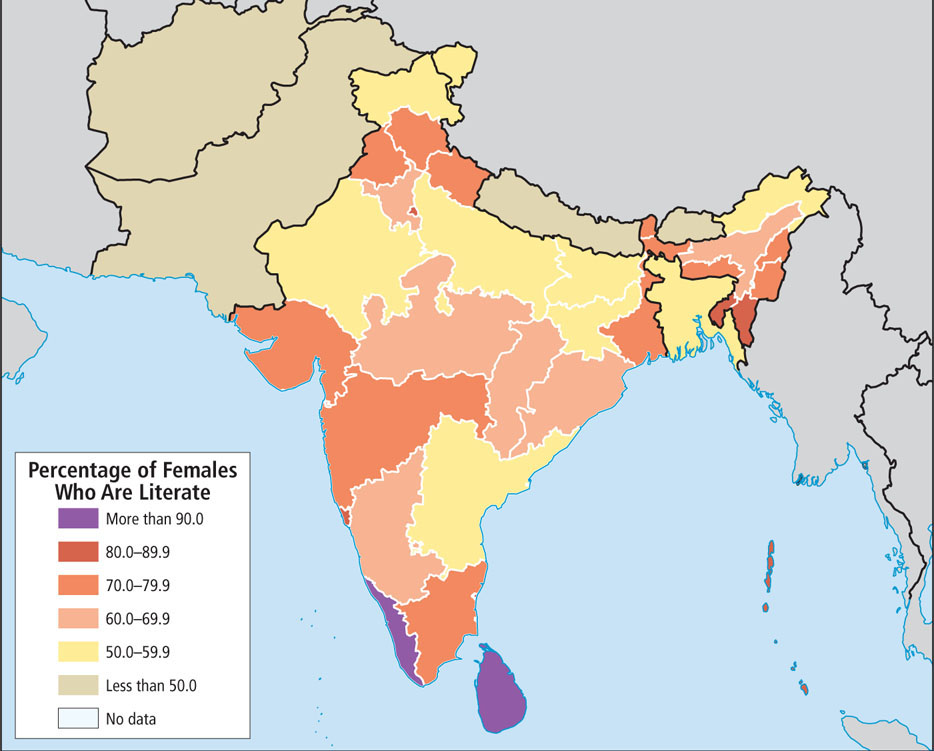

The overall status of women in South Asia is notably lower than the status of men. Even so, young women today have more educational and employment opportunities than did women of a generation ago, and a number of women hold and have held very high positions of power. However, on average, women’s literacy rates, social status, earning power, and welfare are generally lower than those of men, especially in the belt that stretches from the northwest in Afghanistan across Pakistan, western India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Ganga Plain into Bangladesh. Women fare better in eastern and central India and considerably better in southern India and in Sri Lanka. In these latter regions, where literacy rates are higher (Figure 8.21), different marriage, inheritance, and religious practices give women better access to education and resources.  187. SUFI ROCK SINGER FALU BLENDS OLD WITH NEW

187. SUFI ROCK SINGER FALU BLENDS OLD WITH NEW

Urban women in South Asia generally have more individual freedom than rural women have, with many now pursuing professional careers and some becoming involved in politics. Generally speaking, rural women are less free than urban women. In rural India, middle- and upper-caste Hindu women are often more restricted in their movements than are lower-caste women because they have a status to maintain. Meanwhile, lower-caste women who go into public spaces may have to contend with sexual harassment and exploitation from upper-caste men.

The socioeconomic status of Muslim women in South Asia is notably lower than that of their Hindu and Christian counterparts. In India, some of this relates to the generally lower incomes and standard of living for Muslims, which also usually means lower educational levels. Muslim women also work outside the home less than non-Muslim women in India. Low rates of education and workforce participation for women also prevail in Muslim-dominated countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan, although this is less the case in Bangladesh.  191. REMEMBERING PAKISTAN’S FORMER PRIME MINISTER BENAZIR BHUTTO

191. REMEMBERING PAKISTAN’S FORMER PRIME MINISTER BENAZIR BHUTTO

Purdah

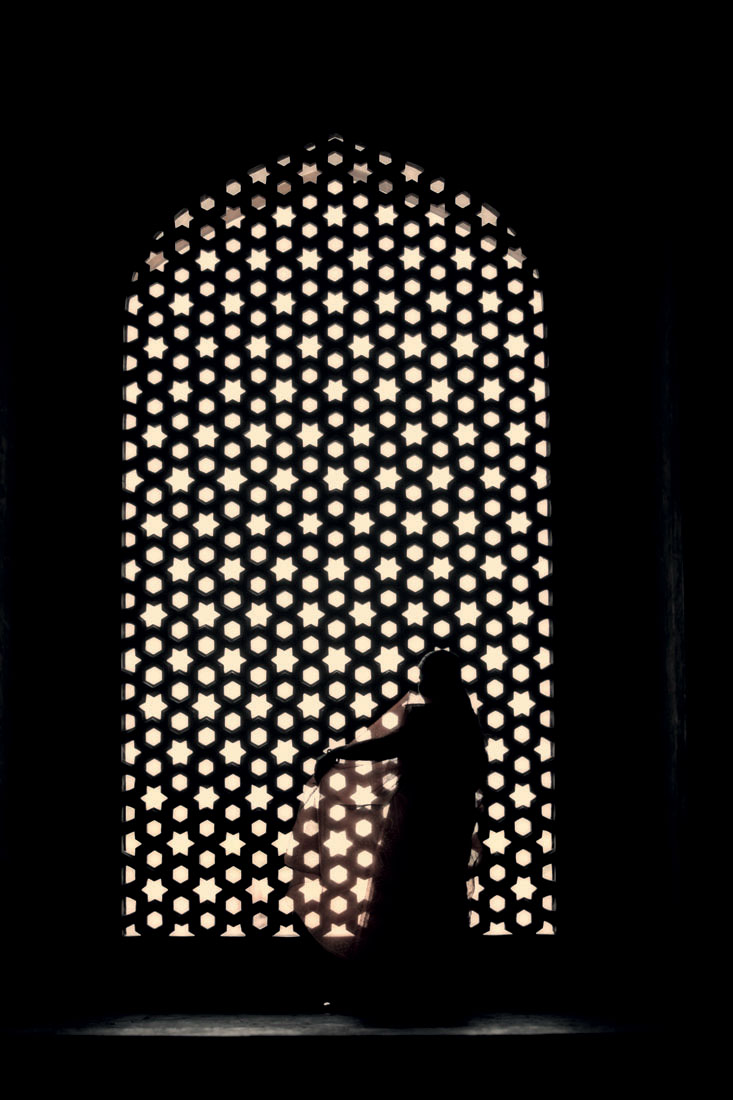

purdah the practice of concealing women from the eyes of nonfamily men

Purdah practices have influenced the architecture of South Asia. Homes are often in walled compounds that seclude kitchens and laundries as women’s spaces. In grander homes, windows to the street are usually covered with lattice screens, known as jalee, that allow in air and light but shield women from the view of outsiders.

Marriage, Motherhood, and Widowhood

Throughout South Asia, most marriages are arranged by the parents of the prospective bride and groom. Especially in wealthier, better-educated families, the wishes of the bride and groom are considered, but in some cases they are not (Figure 8.23). This is especially true of child marriage, when a young girl (often as young as 12 and in some places even younger) is married off to a much older man.

Usually a bride goes to live in her husband’s family compound, where she becomes a source of domestic labor for her mother-in-law. Most brides work at domestic tasks for many years until they have produced enough children to have their own crew of small helpers, at which point they gain some prestige and a measure of autonomy.

Motherhood in South Asia determines much about a woman’s life. A woman’s power and mobility increase when she has grown children and becomes a mother-in-law herself. On the other hand, in some communities, the death of a husband, regardless of cause, is a disgrace to a woman and can completely deprive her of all support and even of her home, children, and reputation. Widows may be ritually scorned and blamed for their husband’s death. Widows of higher caste rarely remarry, and in some areas, they become bound to their in-laws as household labor or may be asked to leave the family home. Most simply become marginalized “aunties” in extended families and help with household duties of all sorts.

Dowry and Violence Against Females

dowry a price paid by the family of the bride to the groom (the opposite of bride price); formerly a custom practiced only by the rich

Until the last several decades, only wealthy families gave the groom a dowry—in this case, a substantial sum that symbolized the family’s wealth, meant to give a daughter a measure of security in her new family.

Ironically, the increases in affluence and education have reinforced the custom of dowry and made it much more common for all families. As more men became educated, their families felt that their diplomas increased their worth as husbands and gave them the power to demand larger and larger dowries. Soon, the practice spread through lower-caste families wanting to upgrade their status. Now the dowries they must pay to get their daughters married can cripple poor families. A village proverb captures this dilemma: “When you raise a daughter, you are watering another man’s plant.”

Gender and Democratization

As countries in South Asia have moved toward more democracy, the status of women in the region has risen. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have all had female heads of state (prime ministers) in the past. However, it is important to note that all of these women were either wives or daughters of previous heads of state. Women have been notably less successful in local elections; and at the parliamentary level, in Bhutan, India, and Sri Lanka, women remain very poorly represented (Table 8.2).

| Country | Percent in Parliament |

|---|---|

| Sri Lanka | 5.8 |

| Bhutan | 8.5 |

| Pakistan | 19.5 |

| Nepal | 33.2 |

| Bangladesh | 19.7 |

| India | 11.0 |

| Afghanistan | 27.7 |

| Source: Women in National Parliaments, Inter-Parliamentary Union Web site at: http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm | |

The very low percentage of women in India’s parliament (see Table 8.2) inspired a confederation of Muslim and Hindu women’s groups to lobby for legislation that would temporarily (for a 15-year trial period) reserve for women one-third of the seats in the lower house of Parliament and in state assemblies. Such quotas are already in place in Pakistan (19.5 percent) and Bangladesh (19.7 percent), but are so far not quite met in Nepal (33.2 percent).

If recent voter turnout and political activism trends continue, there is likely to be a major improvement in female representation in the region’s national parliaments and in local offices.

Women and the Taliban in Afghanistan

Taliban an archconservative Islamist movement that gained control of the government of Afghanistan for a while in the mid-1990s

189. REPORT: DOMESTIC VIOLENCE WIDESPREAD IN AFGHANISTAN

189. REPORT: DOMESTIC VIOLENCE WIDESPREAD IN AFGHANISTAN

190. FRONTRUNNER DOCUMENTARY TELLS STORY OF AFGHAN POLITICIAN WHO INSPIRES WOMEN

190. FRONTRUNNER DOCUMENTARY TELLS STORY OF AFGHAN POLITICIAN WHO INSPIRES WOMEN

VIGNETTE

From behind her microphone at Radio Sahar (“Dawn”), Nurbegum Sa‘idi speaks to a female audience on a wide range of topics. Located in the city of Herat, Radio Sahar is one in a network of independent women’s community radio stations that has sprung up in Afghanistan since early 2003. Radio Sahar provides 13 hours of daily programming consisting of educational items that address cultural, social, and humanitarian matters as well as music and entertainment. For example, one recent broadcast, aimed at informing women of their legal rights, followed the life of a young woman who was physically abused by her husband and his entire family. The woman took the brave step of asking for a divorce. As a result, she was forced into hiding, where she was counseled on the steps she might take next. Another program explored the various concepts of what democracy is and how it might work in Afghanistan. A reported 600,000 Afghan women and youth listen to Radio Sahar while they do their chores.

Girls on the Air, a film by Valentina Monti, reveals the diversity of the ideas and hopes for the future of the young journalists that founded Radio Sahar. A clip can be seen at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6KxtDHbuuY. [Source: Internews Afghanistan. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Men and the Taliban in Afghanistan

The extreme repression of male individuality under the Taliban bears recognition for the hardships it causes. Hypermasculine societies, such as that of the Taliban, tend to repress creativity and emotional sensitivity in males, and that repression can lead to closed minds and even violence toward others, in particular women. Nevertheless, despite the many expressions of hypermasculinity in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere in this region, there is also a long history of alternative expressions of gender (see Figure 8.23C).

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Cell Phones and Literacy

In order to reach women held in deep seclusion, the Afghan government is now making available basic reading and writing lessons on special mobile phones distributed free to Afghan women. The reading/writing software was developed by an Afghan IT firm with USAID assistance. As literacy is achieved by a woman, she can add other subjects with free apps.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The chief locus of status for most women in this region is within the family.

The chief locus of status for most women in this region is within the family. South Asia has had a number of women in very high positions of power, and young women today on average have more educational and employment opportunities than women of a generation ago. However, the overall status of women in the region is notably lower than the status of men, and women’s influence on policy remains low even as the number of women in national parliaments rises above a tiny minority.

South Asia has had a number of women in very high positions of power, and young women today on average have more educational and employment opportunities than women of a generation ago. However, the overall status of women in the region is notably lower than the status of men, and women’s influence on policy remains low even as the number of women in national parliaments rises above a tiny minority. There is a geographic pattern to the socioeconomic status of women, especially with regard to their ability to move through the landscape, their earning power, and their numbers in elective office.

There is a geographic pattern to the socioeconomic status of women, especially with regard to their ability to move through the landscape, their earning power, and their numbers in elective office. Purdah is practiced in both Muslim and Hindu households, but the status of Muslim women is significantly lower than that of their Hindu and Christian counterparts; this is especially so in the north and west, in those parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan where tribal customs include deeply ingrained patterns of deprivation and violence against women and Taliban influence remains high. Generally speaking, women are less restricted in southern and eastern sections of this region.

Purdah is practiced in both Muslim and Hindu households, but the status of Muslim women is significantly lower than that of their Hindu and Christian counterparts; this is especially so in the north and west, in those parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan where tribal customs include deeply ingrained patterns of deprivation and violence against women and Taliban influence remains high. Generally speaking, women are less restricted in southern and eastern sections of this region.

Population Patterns

Geographic Insight 2

Gender and Population: The assumptions that males are more useful to families than females and that females must be supplied with a dowry have resulted in a devaluation of females, leading to a gender imbalance in populations across South Asia. Those who can afford in utero gender-identifying technology may abort female fetuses, while those with fewer resources sometimes commit female infanticide. As a result, adult males significantly outnumber adult females. A second relationship between gender and population is that when females are given opportunities to work outside the home, they tend to choose to have fewer children.

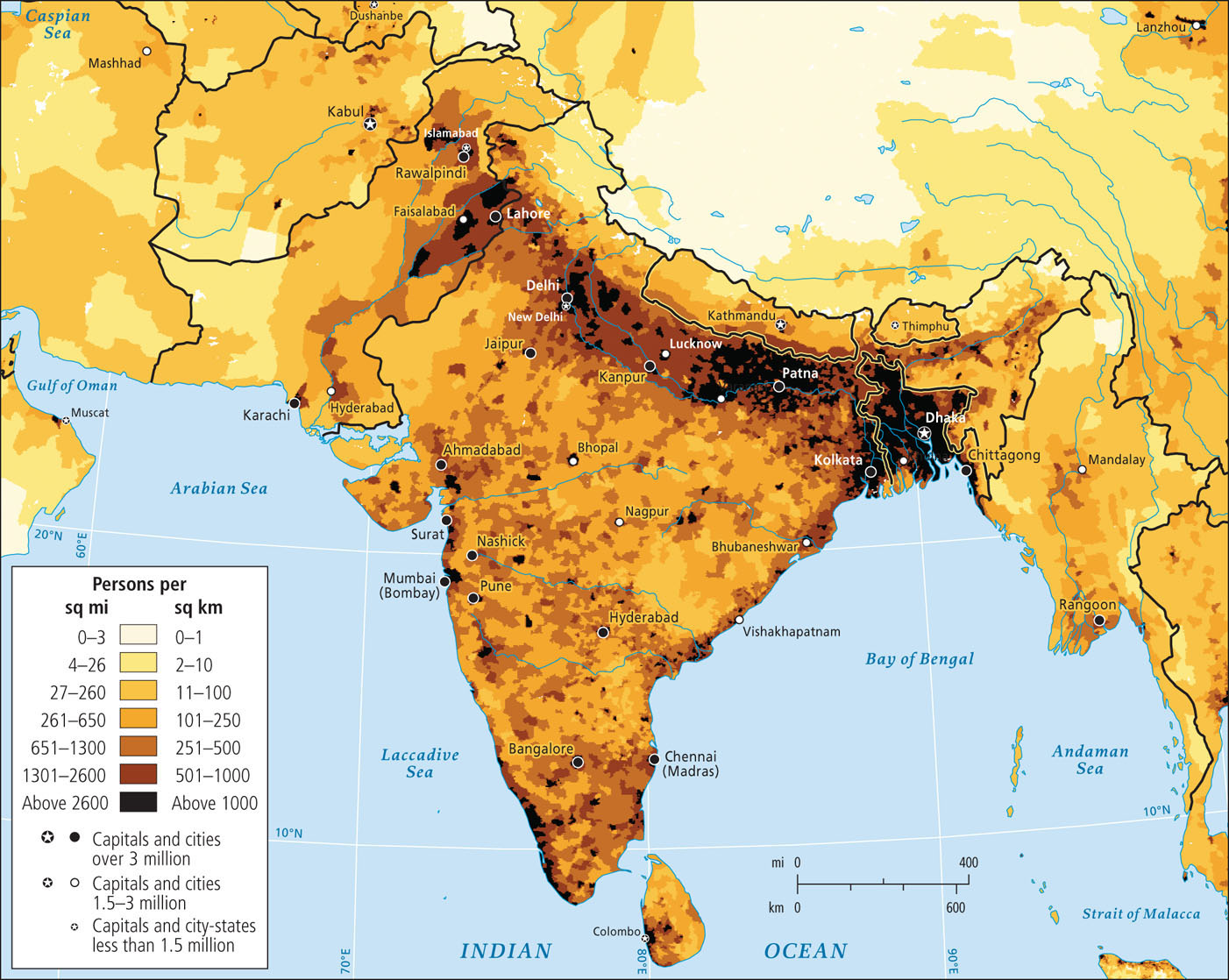

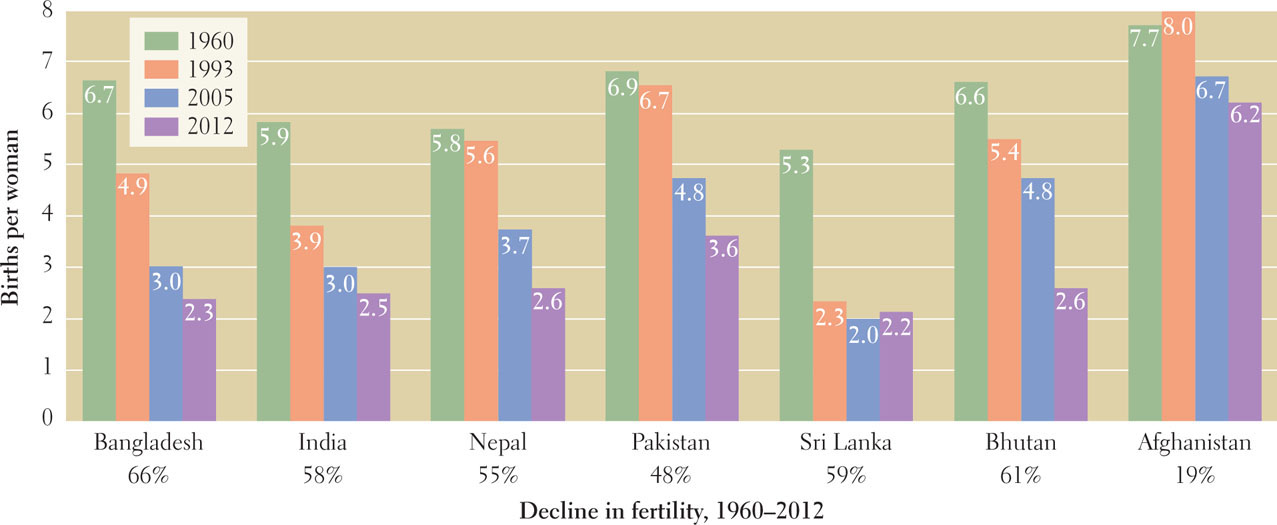

South Asia is the most densely populated region in the world (Figure 8.24; see also Figure 1.8). The region already has more people (1.68 billion) than China (1.35 billion), which has almost twice the land area of South Asia. By 2025, India alone, with 1.46 billion people, will have overtaken China’s 1.40 billion. By 2050, China’s population (if the one-child policy persists) will be shrinking at the rate of about 20 million people per decade, while India’s may still be growing. However, a notable trend is that current rates of growth have slowed to about 1.6 percent and fertility is declining significantly. Only in Afghanistan and Pakistan are fertility rates above 3 children. In Bangladesh and all other countries of the region, women now average just 2.5 children (Figure 8.25). Families are choosing to have fewer children for a variety of reasons, such as improved educational opportunities for women, better health care, and urbanization.

Population densities in this region are highest in the cities that lie just south of the Hindu Kush and Himalayas, and are at their peak in the Ganga-Brahamaputra delta (see Figure 8.24), much of which is a densely occupied, rural agricultural and fishing area.

Slowing Population Growth: Health Care, Urbanization, and Gender

Efforts to slow population growth through better health care have been underway for more than 50 years. Today, urbanization and the rising status of women are helping to reduce the birthrate.

With improved health care, such as diarrhea control techniques (infant rehydration), far fewer babies are dying in infancy. In 1992, infant mortality rates were 91 per 1000 live births in India, 109 in Pakistan, and 120 in Bangladesh. By 2012, those rates were reduced to 47 in India, 68 in Pakistan, and 43 in Bangladesh. With better assurance that their babies will survive to adulthood and be able to care for their elderly parents, couples now choose more often to have just two children.

In addition to improved access to health care as an incentive to have smaller families, the shift in population from rural to urban areas reduces the economic incentive for large families. Whereas children in rural areas (starting at an early age) contribute their labor to farming, thus increasing the family income, the labor of children in urban areas is less likely to boost the family income. Children in urban areas are more likely to go to school, and thus represent a cost to the family for school fees, books, and uniforms. Improvements in the status of women also slow population growth. Research throughout South Asia and elsewhere has shown that women who have the opportunity to go to school and/or to get a paying job tend to delay childbearing and have fewer children.

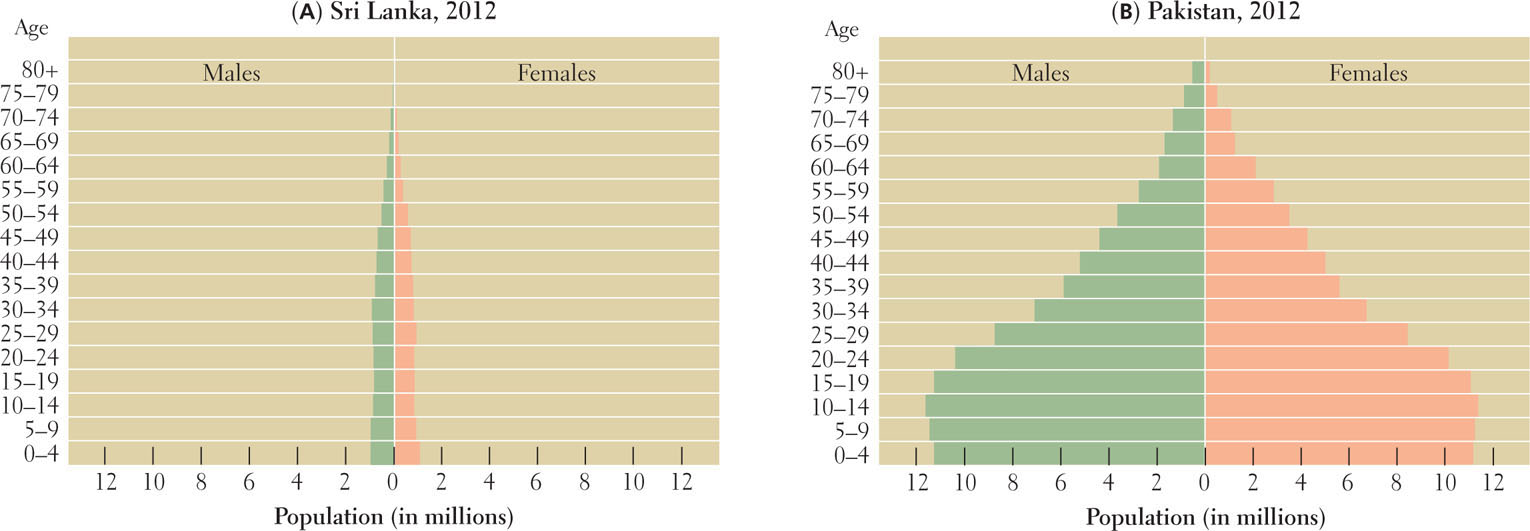

A comparison of the population pyramids as well as some other statistics for Sri Lanka and Pakistan helps illustrate that health care and the status of women influence birth rates (see Figure 8.25 and Figure 8.26A, B). As a country that is far along but not completely through the demographic transition (see Figure 1.10), Sri Lanka has a much higher GNI per capita (U.S.$4943) than Pakistan (U.S.$2550). Health care is generally better in Sri Lanka, as indicated by its much lower infant mortality rate (in 2012, Sri Lanka had 12 deaths per 1000 live births versus Pakistan’s 68 per 1000). Sri Lanka has also worked harder to educate and economically empower its women. Three key indicators of women’s education and empowerment that are associated with reduced fertility rates are much higher in Sri Lanka than in Pakistan: female literacy (90 percent versus 30 percent), the percentage of young women who attend high school (89 percent versus 19 percent), and the percentage of women who work outside the home (36 percent versus 16 percent). Surprisingly, Sri Lanka has achieved all this with an urbanization rate of just 15 percent, far lower than that of Pakistan’s 35 percent.

Despite Pakistan’s rather dismal statistics compared to those of Sri Lanka, its population pyramid does indicate that birth rates have slowed significantly (notice that the bottom of the pyramid in Figure 8.26B narrows noticeably). If this trend continues, Pakistan, as well as all South Asian countries except Afghanistan, will enjoy what is called the demographic dividend: a bulge of young people entering the workforce and choosing to have fewer children, who will thus have the time and energy to study, to work, and to contribute to the economy and civil society. Down the road, however, South Asian countries that have had a demographic dividend will have to deal with an aging population for which there are fewer younger caregivers and taxpayers to support the elderly.  185. CHILD LABOR PERSISTS IN INDIA DESPITE NEW LAWS

185. CHILD LABOR PERSISTS IN INDIA DESPITE NEW LAWS

Gender Imbalance

South Asian populations have a significant gender imbalance because of cultural customs that make sons more likely than daughters to contribute to a family’s wealth. A popular toast to a new bride is “May you be the mother of a hundred sons.” Many middle-class couples who wish to have sons hire high-tech laboratories that specialize in identifying the sex of a fetus. The intention is to abort female fetuses. This practice is now illegal, but it persists. Poorer South Asians may neglect the health of girl children, with some even committing female infanticide (the dowry implications are discussed).

186. GIRLS PAY PRICE FOR INDIA’S PREFERENCE FOR BOYS

186. GIRLS PAY PRICE FOR INDIA’S PREFERENCE FOR BOYS

After the 2001 census, India took a stronger stand against selecting for male children. A follow-up sex-ratio survey in five Indian states from 2004 to 2006 showed some improvement in all five states, with Tamil Nadu coming closest to a normal sex ratio, probably due to an especially aggressive campaign for women’s health and against sex-selective abortions.

Gender imbalance of the magnitude India is facing could create serious problems, such as surges in crime and drug abuse related to the presence of so many young men with no prospect of having a family. In all cultures, the possibility of having a family is a stabilizing influence for young men. The efforts of the state of Kerala to overcome gender imbalance by putting more attention to women’s development bear watching. Kerala’s government has made women’s development a priority, funding education for women well beyond basic levels. The results are reflected in its female literacy rate, which is the highest in India at 87.8 percent (the average for India as a whole is 54.5 percent; see Figure 8.21 for the state female literacy map), and in the number of women who work outside the home. In Kerala, daughters, far from being viewed as an economic liability to the family, are seen as an asset. Women can travel the public streets alone and in groups; they commonly work in public places, many in high positions in government, education, health care, IT industries, and other professions.  188. GLOBAL POPULATION BOOM PUTS ‘MEGA’ PRESSURE ON CITIES IN DEVELOPING WORLD

188. GLOBAL POPULATION BOOM PUTS ‘MEGA’ PRESSURE ON CITIES IN DEVELOPING WORLD

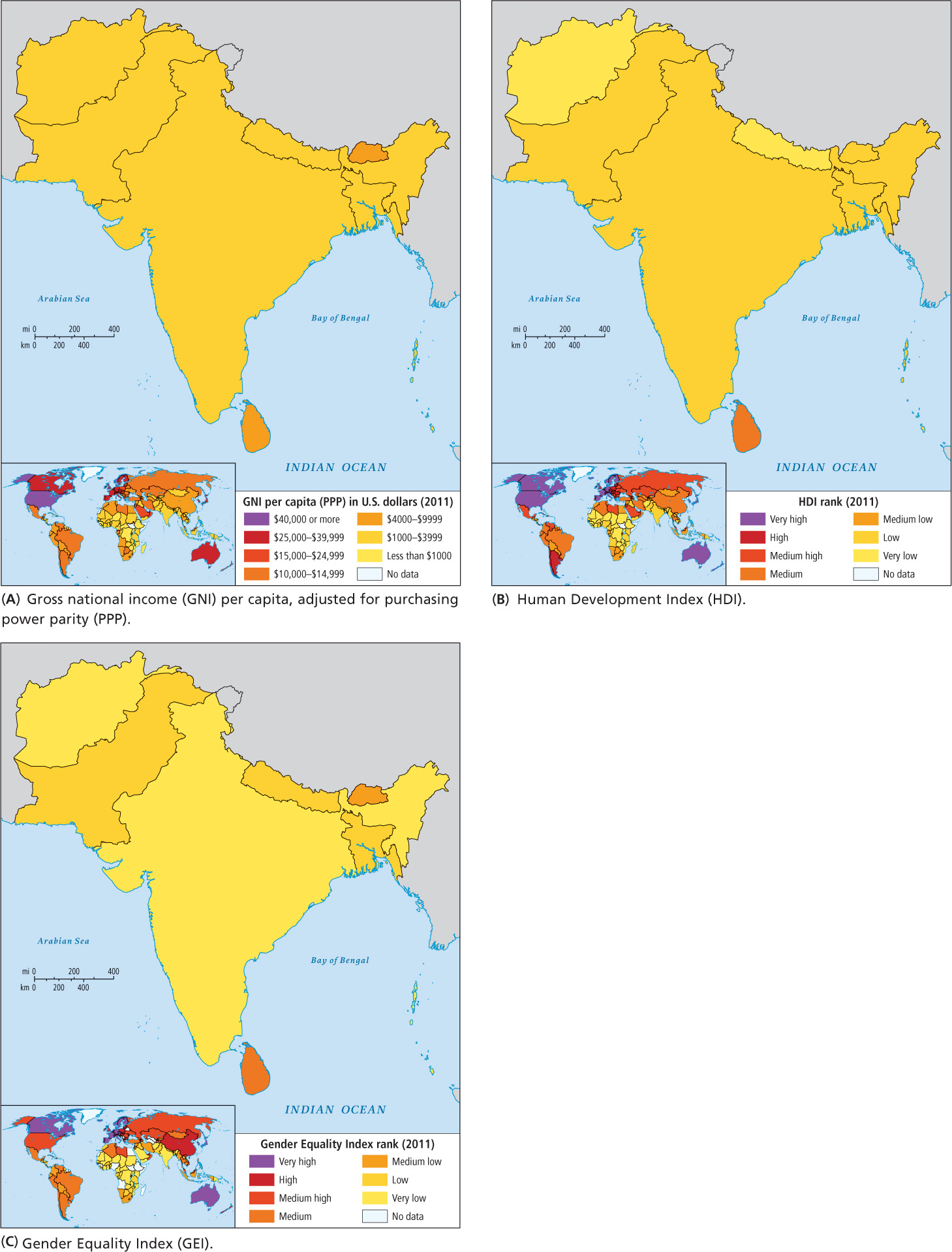

Measures of Human Well-Being

The maps of human well-being in South Asia (Figure 8.27) show that the overall state of human well-being in South Asia is marginal, with nearly the entire region ranking in the medium-low levels. The region as a whole has an average GNI per capita (PPP) below U.S.$4000 (see Figure 8.27A). Of course, the huge country of India has many cities and a few states that rank above this level (Haryana, for example; see Figure 8.30), but these variances are lost in the countrywide average. A bright spot in these data is that disparity of wealth (the gap between rich and poor) is quite narrow in South Asia. Some might say this is related to the broad-based democracies found in this region. Certainly the provision of services is better and more consistent here than in Africa, for example. In per capita GNI, however, Nepal ranks very low ($1160), Afghanistan does only slightly better ($1416), and Bangladesh is also only marginally better ($1529).

On the Human Development Index (HDI), there is even less variation (see Figure 8.27B). All of the South Asian countries rank either low or very low, with the slight exception of Sri Lanka (medium). These HDI levels indicate that the well-being of citizens in these countries is worse than the worldwide average in terms of adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment. In fact, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh have all lost HDI rank in recent years, a fact that may be related to the global economic recession.

Figure 8.27C shows how well countries are ensuring gender equality (GEI) in three categories: reproductive health, political and educational empowerment, and access to the labor market. Again, South Asia ranks in the low and very low categories, with only Bhutan and Sri Lanka ranking in the medium and medium- low categories. Based on the global thumbnail map, it is clear that South Asia is in a league with only North Africa, Southwest Asia, and Mexico, but virtually nowhere else.

While South Asia’s record in human development is not impressive and may even be backsliding a bit during the global recession, there has been economic progress across the region, and in fact, some remarkable technological and theoretical innovations in the region have already contributed to development elsewhere, as the next section shows.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 2Gender and Population There is a significant and often extreme gender imbalance in South Asia, originating in cultural customs that make sons more likely to contribute to a family’s wealth than daughters. Too often this imbalance results in outright discrimination and oppression that affects women in every stage of their lives. Also, population growth tends to decline sharply when women are educated.

Geographic Insight 2Gender and Population There is a significant and often extreme gender imbalance in South Asia, originating in cultural customs that make sons more likely to contribute to a family’s wealth than daughters. Too often this imbalance results in outright discrimination and oppression that affects women in every stage of their lives. Also, population growth tends to decline sharply when women are educated. Population growth is slowing across the region, but the momentum provided by a young population means that growth will continue for the foreseeable future.

Population growth is slowing across the region, but the momentum provided by a young population means that growth will continue for the foreseeable future. The overall average state of human well-being in South Asia is marginal, with nearly the entire region ranking at the medium-low levels.

The overall average state of human well-being in South Asia is marginal, with nearly the entire region ranking at the medium-low levels.