Economic Issues

South Asia is a region of startling economic incongruities. India is a good example; it is home to hundreds of millions of desperately poor people, but it is also a global leader in the computer software industry and in engineering innovation. It is celebrated for being the largest democracy in the world; yet its poor are often left out of the political process and bypassed or even harmed by economic reforms. Despite these contrasts, overall, most countries in this region—especially India—are on their way up.

Economic Trends

Agriculture still employs more than 50 percent of the workers in South Asia, but the contribution of agriculture to most national economies is much lower, averaging less than 20 percent of the GNI for the region. The industrial sector employs far fewer people but produces between one-quarter and one-third of GNI in all countries except Nepal, Bhutan, and Afghanistan. The service sector has expanded more rapidly than either agriculture or industry and now produces more than half of the GNI in every country except Afghanistan and Bhutan. Rapid development and self-sufficiency have been the dream for all parts of the region since the end of the colonial era in the 1940s. Successful measures to encourage economic modernization include an emphasis on IT and other high-tech industries as well as the automotive industry in India; textile and leather manufacturing in Pakistan; and innovative microfinancing strategies pioneered in Bangladesh. Less successful, but still promising, is the development of modernized agribusiness, which involves all three sectors of agriculture, industry, and services. Especially in India, but also in Pakistan and Bangladesh, agribusiness has drastically increased the amount of food available.

Food Production and the Green Revolution

Geographic Insight 3

Food and Urbanization: Due to changes in food production systems in South Asia, food supplies and incomes of wealthy farmers have increased. Meanwhile, impoverished agricultural workers, displaced by new agricultural technology, have been forced to seek employment in cities, where they often end up living in crowded, unsanitary conditions and must purchase food.

Agricultural production per unit of land has increased dramatically over the past 50 years, especially in parts of India; nonetheless, agriculture remains the least efficient economic sector, meaning that it has the lowest return on investments of land, labor, and cash. Figure 8.28 shows the distribution of agricultural zones in South Asia.

Until the 1960s, agriculture across South Asia was based largely on traditional small-scale systems (the average farm holding in South Asia is still less than 2 acres) that managed to feed families in good years, but often left them hungry or even starving in years of drought or flooding. Moreover, these systems did not produce sufficient surpluses for the region’s growing cities. Even now, cities must import food from outside South Asia. Much of South Asia’s agricultural land is still cultivated by hand, and for decades, agricultural development was neglected in favor of industrial development, especially in India (discussed below). Nonetheless, by the 1970s, important gains in agricultural production had begun.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the green revolution (see Chapter 1) boosted grain harvests dramatically through the use of new agricultural tools and techniques. Such innovations included seeds bred for high yield and for resistance to disease and wind damage; fertilizers; mechanized equipment; irrigation; pesticides; herbicides; and double-cropping (producing two crops consecutively per year). To a lesser extent, the increase in the amount of land under cultivation also contributed to a greater yield. Where the new techniques were used, yield per unit of farmland improved by more than 30 percent between 1947 and 1979, and both India and Pakistan became food exporters.

Despite the achievements of the green revolution, the shortcomings have been numerous. Some Indian states, such as Punjab and Haryana, which have extensive irrigation networks, have increased prosperity tremendously for some, but many poor farmers unable to afford the special seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and new equipment could not compete and had to give up farming. Most migrated to the cities, where their skills matched only the lowest-paying jobs.

South Asia needs alternatives to standard green revolution strategies because it will have difficulty maintaining current levels of food production over the long term. The green revolution’s dependency on chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and high levels of irrigation all contribute to aquifer depletion, waterway pollution, increased erosion, and the loss of soil fertility through the buildup of salt in soils. Soil salinization (see Chapter 6) is already reducing yields in many areas, such as the Pakistani Punjab, which is Pakistan’s most productive—but highly irrigated—agricultural zone.  192. TECHNOLOGY KEY TO PRODUCING MORE FOOD

192. TECHNOLOGY KEY TO PRODUCING MORE FOOD

agroecology the practice of traditional, nonchemical methods of crop fertilization and the use of natural predators to control pests

One reason that the green revolution has managed to increase food supplies but not eliminate hunger and malnutrition is that food tends to go to those with money to spend. As noted previously, agricultural modernization usually pushes unskilled farm workers off the land and into precarious underemployment. Between 1970 and 2001, the amount of food produced per capita in South Asia increased 18 percent, and the proportion of undernourished people dropped from 33 percent of the population to 22 percent. Nonetheless, 22 percent of nearly 1.6 billion is 352 million people—roughly half of the world’s total undernourished population. Because of corruption and social discrimination, government programs that provide food to the poor have generally failed to reach those most in need. For example, in India, despite massive resources devoted to improve child nutrition, about half of the children show signs of malnutrition.

Microcredit: A South Asian Innovation for the Poor

microcredit a program based on peer support that makes very small loans available to very low-income entrepreneurs

195. NOBEL PEACE PRIZE GOES TO BANGLADESH’S “BANKER TO THE POOR”

195. NOBEL PEACE PRIZE GOES TO BANGLADESH’S “BANKER TO THE POOR”

The microcredit loans often pay for the start-up costs of small enterprises, which include such wide-ranging ventures as cell phone–based services, chicken raising, small-scale egg production, the construction of pit toilets, and the distribution of home water purification systems. Potential borrowers (more than 90 percent of whom are women) are organized into small groups that are collectively responsible for repaying any loans to group members. If one member fails to repay a loan, then everyone in the group is denied loans until the loan is repaid. This system, reinforced with weekly meetings, creates incentives to repay (Figure 8.29). The repayment rate on the loans is extremely high, averaging around 98 percent—much higher than most banks achieve.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Microcredit: A Bangladeshi Innovation

So far, the Grameen Bank has been an enormous success in Bangladesh, where it has loaned over U.S.$8 billion to more than 8 million borrowers. Similar microcredit projects have been established in India and Pakistan and throughout Africa, Middle and South America, North America, and Europe. In 2006, Dr. Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in microcredit. In 2009, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama.

Industry over Agriculture: A Vision of Self-Sufficiency

After independence from Britain in 1947, the new leaders in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka tended to favor industrial development over agriculture. Influenced by socialist ideas and industrial success in the Soviet Union, they believed that government involvement in industrialization was necessary to ensure the levels of job creation that would cure poverty. They also wanted their respective countries to become self-sufficient and be independent of manufactured goods imported from the industrialized world (see Chapter 3 for a discussion of import substitution industrialization). To reach their goal of self-sufficiency, governments took over the industries they believed to be the linchpins of a strong economy: steel, coal, transportation, communications, and a wide range of manufacturing and processing industries.

South Asian industrial policies in the decades after independence generally failed to meet their goals. The emphasis on industrial self-sufficiency was not suited to countries that had such large agricultural populations. In India, for example, governments invested huge amounts of money in a relatively small industrial sector—even today industry employs only 14 percent of the population, compared with the 52 percent employed in agriculture. Since such a small portion of the population directly benefited from this investment, industrialization failed to significantly increase South Asia’s overall prosperity.

Another problem was that the measures intended to boost employment often contributed to inefficiency. One policy encouraged industries to employ as many people as possible, even if they were not needed. So, for example, until recently, it took more than 30 Indian workers to produce the same amount of steel as 1 Japanese worker. Consequently, for years, Indian steel was not competitive in the world market. In addition, as in the former Soviet Union, decisions about which products should be produced were made by ill-informed government bureaucrats and were not driven by consumer demand. Until the 1980s, items that would improve daily life for the poor majority, such as cheap cooking pots or simple tools, were produced only in small quantities and were of inferior quality. At the same time, there was a relative abundance of large kitchen appliances and large cars that only a tiny minority could afford.

Economic Reform: Globalization and Competitiveness

Geographic Insight 4

Globalization and Development: Globalization benefits populations unevenly. Educated and skilled South Asian workers with jobs in export-connected and technology-based industries and services enjoy better lives. Low-skilled workers, however, in both urban and rural areas, are left with demanding but very low-paying jobs.

During the 1990s, much of South Asia began to undergo economic reforms aimed at increasing competitiveness and creating secure jobs in the private sector. In many other world regions, structural adjustment programs (SAPs; see Chapter 3) were mandated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In India, by contrast, in response to an earlier financial crisis in the 1980s, the government itself initiated economic reforms. Although privatization of India’s public sector industries and banks has proceeded slowly, it has been arguably more successful than SAPs and similar reforms imposed by the IMF and the World Bank in other countries.

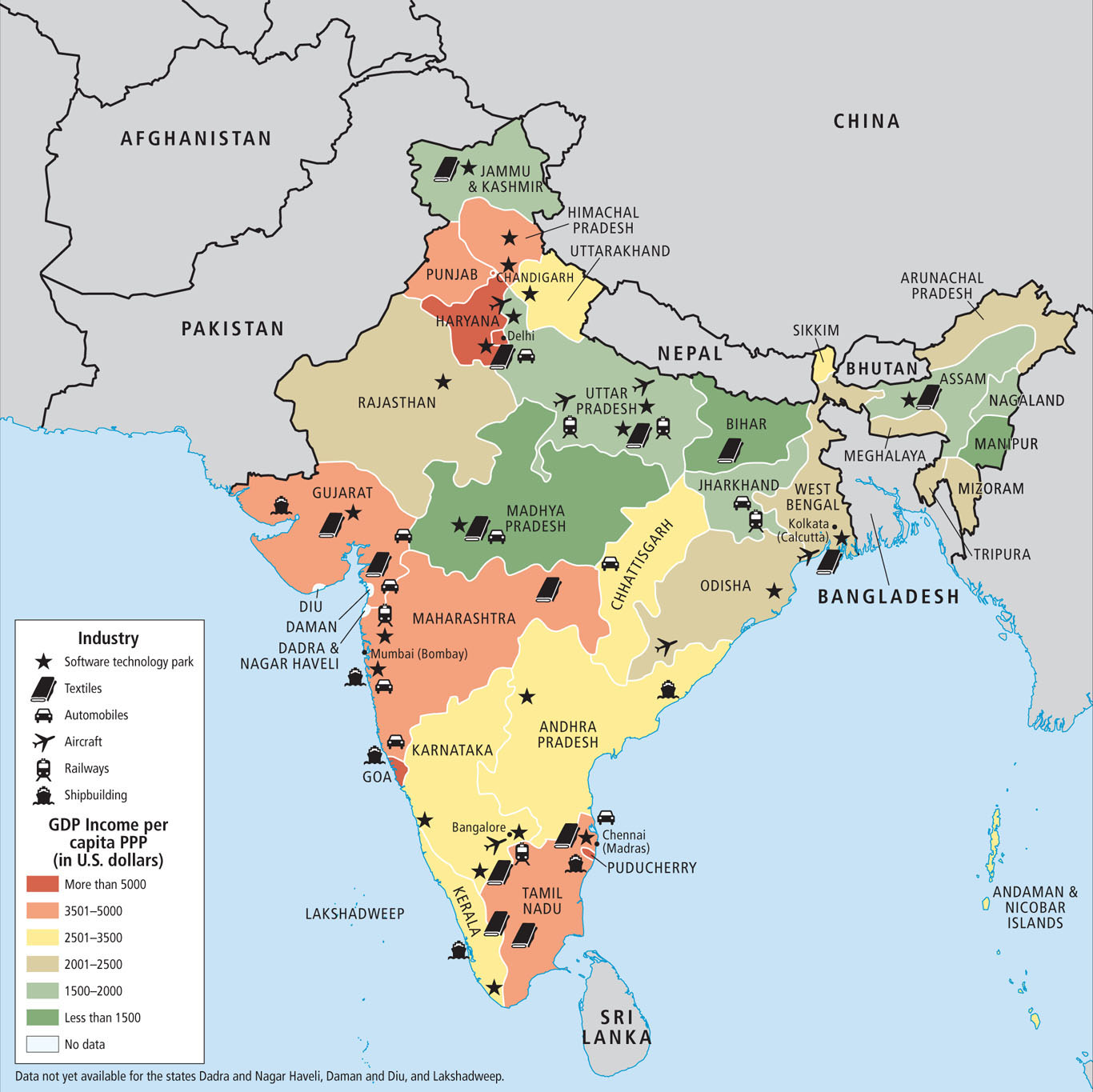

India is now using the economic reforms to free its private companies from a maze of regulations, enabling both foreign and Indian companies to invest heavily in manufacturing and other industries (Figure 8.30). Some Indian companies are quite innovative, such as Reva, which builds economical electric cars for India’s middle class. Foreign auto companies are also flocking to India, drawn by its large and cheap workforce, its excellent educational infrastructure (for the middle and upper classes), and especially by its large, pent-up domestic demand for manufactured goods of all sorts. Nearly every major global automobile company is currently establishing significant manufacturing facilities somewhere in India—producing everything from economical first cars for Indian families to luxury brands such as Mercedes-Benz for wealthier Indians. So many global manufacturers have flocked to India in recent years that the country is challenging China as an exporter of manufactured goods. The hope is that as the current recession subsides and manufacturing jobs increase, many of India’s urban poor will see their incomes rise, and then they too will increase their consumption of Indian-made products, thus fueling further growth. By 2009 (the latest date for which comparable figures are available), GDP per capita (PPP) had risen in all Indian states (see Figure 8.30), and the average per capita income (PPP) in India in 2011 was U.S.$3468, nearly ten times higher than it was in 1992.

offshore outsourcing the contracting of certain business functions or production functions to providers in areas where labor and other costs are lower

Major global finance firms are increasingly hiring the highly skilled workers on Mumbai’s “Wall Street”—Dalal Street—to provide finance and accounting services. Stiff global competition makes cost cutting imperative for finance firms, and India’s relatively low salaries provide a solution. While a junior analyst from an Ivy League school costs $150,000 a year in the United States, a graduate of a top Indian business school costs only $35,000 a year in India. That Indian employee’s salary, however, buys a much higher standard of living than the U.S. employee would have. In fact, well-educated Indian migrants in the United States are now returning home to take these seemingly low salaries because they can still live well and join this exciting development phase in their home country. This trend of return-migration could eventually happen across the South Asian region.

To facilitate trade between countries and to lure extra-regional investors into this huge market, South Asia has attempted to create region-wide free trade agreements. Agreements were scheduled to be implemented in 2012, but progress has been slow and uneven. Because of its size, India is the biggest player in free trade discussions. India is a major supplier for Sri Lanka and Bangladesh but buys little from them in return. And although the potential for trade between India and Pakistan is great and could include cars, cotton, chemicals, and food imported from India, as yet the two countries have only a small trade relationship, with India buying very little from Pakistan. The ongoing political and border disputes inhibit progress.

Letting in Foreign Firms and Free Trade

Until the 1990s, South Asia, and specifically India, avoided exposing its economy to foreign competition. Even today, while much of India’s economy is now open to foreign competition, retail companies like IKEA and Walmart are not being allowed in for fear they will drive local companies, producers, and even farmers out of business. Resistance to further opening for foreign competition also comes from older generations, especially the many older government officials who have power over how regulations are developed and implemented. These people were raised and educated during the early post-colonial era when South Asian economic policies centered on import substitution (see Chapter 3). Many of the region’s growing middle-class consumers have long supported opening economies further to foreign competition, especially in the retail sector. Since consumers are also voters, the older generation may eventually be swayed.

Even within India there are blocks to freer trade across state borders. The maze of regulations mentioned earlier extends down to the interstate level, and there is little reconciliation of the states’ varying tax policies. Trade across state borders is so hampered that it has been suggested that India needs a free trade agreement with itself.

The impact of India’s self-implemented economic reforms on wealth distribution is the subject of much debate. The highly skilled and educated urban middle and upper classes have gained the most by far. India’s middle class now stands at 50 million—as yet, a tiny minority of India’s 1.2 billion—but is likely to grow dramatically to perhaps 600 million by 2030. However, the new economic policies are producing wider urban/rural income disparities.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 3Food and Urbanization While food production has improved dramatically, many poor farmers in India, unable to afford special seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and new equipment required for green revolution agriculture, can no longer compete and have gone hungry. They often give up farming; some have moved to urban areas, hoping to find jobs so they can purchase food. Other farmers have successfully adopted agroecology methods.

Geographic Insight 3Food and Urbanization While food production has improved dramatically, many poor farmers in India, unable to afford special seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and new equipment required for green revolution agriculture, can no longer compete and have gone hungry. They often give up farming; some have moved to urban areas, hoping to find jobs so they can purchase food. Other farmers have successfully adopted agroecology methods. The Grameen Bank and its strategy of microcredit have been very successful in Bangladesh; this method of small-loan financing has spread around the world, including to the United States.

The Grameen Bank and its strategy of microcredit have been very successful in Bangladesh; this method of small-loan financing has spread around the world, including to the United States. The service sector is growing rapidly in all countries and dominates most economies in terms of the contributions made to GNI (or GDP), but this sector still employs a relatively small proportion of workers.

The service sector is growing rapidly in all countries and dominates most economies in terms of the contributions made to GNI (or GDP), but this sector still employs a relatively small proportion of workers. Geographic Insight 4Globalization and Development To take advantage of India’s large, college-educated, low-cost workforces, foreign companies are outsourcing an increasing number of jobs to Indian cities like Bangalore, Mumbai, and Ahmadabad. India’s current manufacturing boom is benefiting from the offshore outsourcing that started in the 1990s. However, low-skilled workers in rural India are not benefiting nearly as much as others from these changes.

Geographic Insight 4Globalization and Development To take advantage of India’s large, college-educated, low-cost workforces, foreign companies are outsourcing an increasing number of jobs to Indian cities like Bangalore, Mumbai, and Ahmadabad. India’s current manufacturing boom is benefiting from the offshore outsourcing that started in the 1990s. However, low-skilled workers in rural India are not benefiting nearly as much as others from these changes. Foreign firms are now allowed to invest directly in India if they meet certain rules.

Foreign firms are now allowed to invest directly in India if they meet certain rules.