9.1 9 East Asia

9.1.1 Geographic Insights: East Asia

Geographic Insights: East Asia

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Climate Change and Water: East Asia has long suffered from alternating droughts and devastating floods, and scientists fear that these hazards will only intensify with climate change. Meanwhile, the rivers of China, many of which originate in the Tibetan and neighboring plateaus, are dependent both on seasonal rainfall cycles and on glacial meltwater that are expected to diminish over the next few decades.

2. Food and Globalization: East Asian countries have enough economic development to be able to buy food on the global market, but they are less able to produce sufficient food domestically. Much agricultural land has been lost to urban and industrial expansion and to mismanagement; meanwhile the increase in the region’s affluence has led to a demand for more imported food.

3. Urbanization and Development: China’s move to join the global economy more than three decades ago has led to spectacular urban growth, a stronger emphasis on consumerism, and a massive rise in industrial and agricultural pollution of the air, water, and soil.

4. Power and Politics: As economic development has grown across East Asia, pressures for more political freedoms have also risen. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are now among the more politically free places in the world, and pressure for similar levels of freedom is intensifying in China and North Korea.

5. Population and Gender: China’s “one-child policy” has created a shortage of females. Long-standing cultural preferences for male children mean that if their one child will be female, many parents choose abortion or put the baby up for adoption. The shortage of females is accentuated by the fact that many women are deciding to have a career rather than to marry and have children.

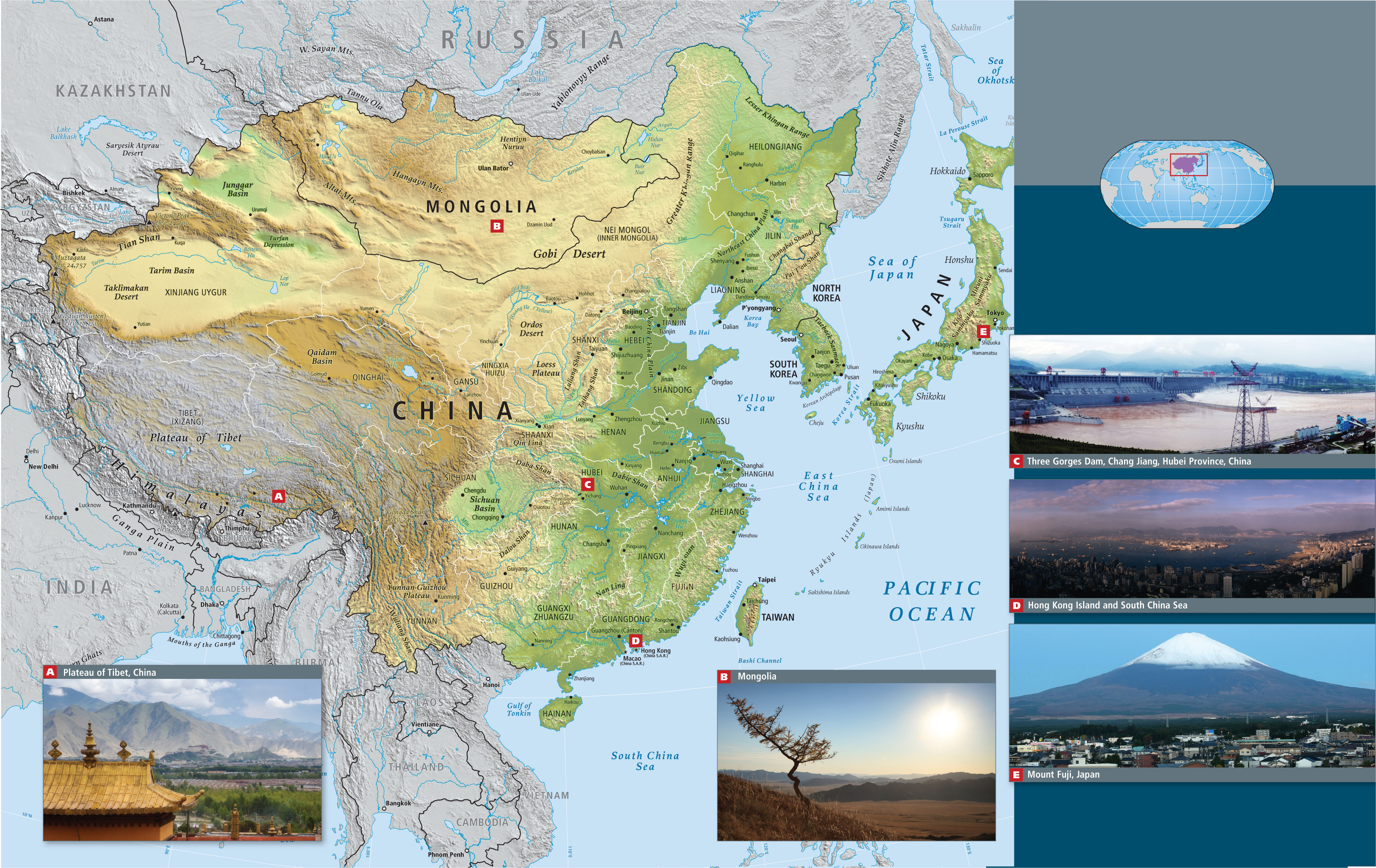

The East Asian Region

East Asia (see Figure 9.1) is the most populous world region, with 1.6 billion people. The region is dominated by China, which has a population of 1.35 billion. China’s dominance is not due only to its population, but also to its physical size and its economic role in the global economy. Just as the astounding economic rise of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has been the model for developing countries over the past 50 years, the opening of China to the global economy will continue to transform East Asia and the world for 50 years more. The changes underway in this region today are immense. Incomes have risen and cities have boomed, but so have air and water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, there are signs that new, cleaner technologies may mitigate these pollution problems.

The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the plight of workers in the East Asian economy, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

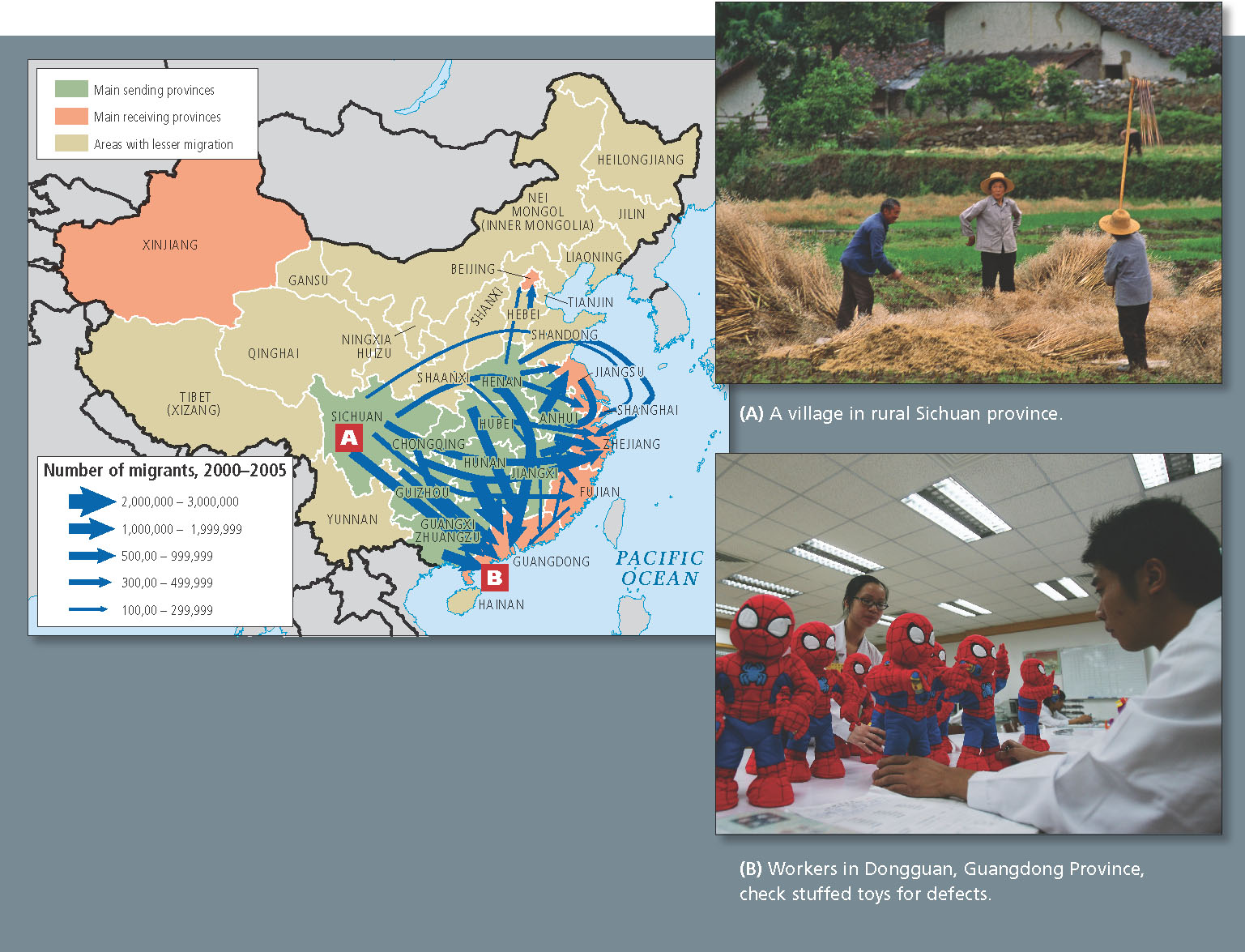

In 2000, at age 18, Li Xia (Li is her family name) left her farming village in China’s Sichuan Province (Figure 9.2A) for the city of Dongguan in the Guangdong Province of southern China. She was accompanied by two friends. A few months earlier, the government had taken their families’ farmland for an urban real estate project, paying compensation of only U.S.$2000 per family. The three young women accepted an offer to work in a Dongguan toy factory so they could send money back to their families, who now have to pay cash for food and housing (see Figure 9.2B).

When the young women arrived in the city, they joined 5 million other recent internal migrants. Sixty percent, like Li Xia, had migrated illegally, without government-approved residency rights, and thus were dependent on their employers for housing. As did many others, Li Xia and her friends soon found that the labor recruiters had lied about their wages. Per month they would be paid not U.S.$45, as promised, but U.S.$30. In addition, they would work 12-hour shifts in 100°F heat, receive no overtime pay, and have only 1 day off a month. But there was no point in protesting. Their families in Sichuan needed the money they would send home, and the recruiters purposely brought in thousands of extra workers to replace any complainers.

Xia felt better when she saw that the toy factory was a clean, modern building known locally as the “Palace of Girls” (nearly all 3500 employees were female). Within a day, she had completed her training, signed a 3-year contract, and mastered her task of putting eyes on stuffed animals destined for toddlers in the United States and Europe. Her enthusiasm faded, however, when she learned that she and her friends would be spending much of their money on the expensive but low-quality food provided by the company, and would be sharing one small room and a tiny bath with eight other women and a rat or two.

In less than 6 months, Xia broke her contract and returned home to her village in Sichuan. There, using ideas and assertiveness she had gained from her time in Dongguan, she opened a snack stand. In just 1 month, she made ten times her investment of U.S.$12. But Xia yearned to return to the southern coast to try again for a well-paid factory job. A few months later, she returned to Dongguan with her sister, leaving the stand to her sister’s husband (who also cared for the couple’s baby).

Since her first arrival, the city had grown by 20 percent and now had 1400 foreign companies trying to hire thousands of workers. Through connections, Xia and her sister found jobs requiring midlevel skills in a Taiwanese-owned fiber optics factory at twice the wages Xia had earned at the toy factory. One year after her first trip to Dongguan, Xia was making a bit more than U.S.$100 a month, enough to live relatively comfortably with only three roommates. She had prospects for a raise, and she was sending money home and once again saving, this time to open a bar in her home village. [Sources: Washington Post, National Public Radio, and Wall Street Journal. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

The experiences of Li Xia and her sister illustrate first how the needs of rural areas are being subverted to the needs of China’s burgeoning cities. Developers are increasingly targeting rural land, and farmers are rarely given a fair price for their land. The reason for this is that the individual Chinese farmer does not own farmland; he or she only leases it from the local government, which may be inclined to sell the land to high-bidding developers. Meanwhile, urbanization, globalization, and changes in gender roles are transforming East Asia as millions of rural young adults are flocking to East Asia’s coastal cities to work in factories there (see the Figure 9.2 map). There they produce goods for sale on global markets, learn new skills, and gain new confidence.

hukou system the system in China that ties people to their place of birth; each person’s permanent residence is registered and any person who wants to migrate must obtain permission from authorities to do so

floating population the Chinese term for people who live illegally in a place other than their required (hukou) household registration location; many are jobless or underemployed people who have left economically depressed rural areas for the cities

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The migration of people from rural China to cities includes 160 million workers who have moved without legal papers and who now constitute half of China’s urban labor force.

The migration of people from rural China to cities includes 160 million workers who have moved without legal papers and who now constitute half of China’s urban labor force. Most rural workers who have moved to China’s cities without official permission are in low-paying jobs with little or no access to social services or education.

Most rural workers who have moved to China’s cities without official permission are in low-paying jobs with little or no access to social services or education.