China‘s Northeast

China’s northeast consists of the Loess Plateau, the North China Plain, and the Far Northeast subregion (Figure 9.32). The Loess Plateau and the North China Plain are the ancient heartland of China. By the eighth century, the city of Chang’an (now encompassed by the city of Xian) had 2 million inhabitants in the urban region and may have been the largest city in the world. After 900 c.e., the center of Chinese civilization shifted to the North China Plain, but the Loess Plateau remained a crucial part of China. Xian served as the eastern terminus of the Silk Road that connected China with Central Asia and Europe (see Figure 5.9).

loess windblown material that forms deep soils in China, North America, and central Europe

The Loess Plateau

An unusually diverse mixture of peoples from all over Central Asia and East Asia have found the Loess Plateau a fertile, though challenging, place to farm and herd. Among the many culture groups that share this densely inhabited and productive plateau are the Hui and the Han of China and, particularly in the western reaches, Mongols, Tibetans, Uygurs, and Kazakhs. Many of the plateau inhabitants farm cotton and millet in irrigated valley bottoms or raise sheep on the drier grassy uplands. China’s largest coal reserves are also found here.

Thousands of years of human occupation have stripped the plateau of its ancient forests, leaving only grasses to anchor the loess. Because the loess is so thick—hundreds of feet deep in many areas—and the winds persistent, some people have carved residences and animal sheds below the surface of the plateau (Figure 9.33). Torrential rains cut deep gullies into the loess, and such gullies now cover much of the landscape, causing people to abandon the agricultural terraces. For decades, the government has maintained a revegetation campaign to stabilize slopes (see the vignette).

The North China Plain

The North China Plain is the largest and most populous expanse of flat, arable land in China. Since the sixth century, it has been home to most of the imperial families, and from this region the Han Chinese have dominated the country.

Today the North China Plain is one of the most densely populated spaces in the country: 370 million people—more than in the whole of North America—live in a space about the size of France. The majority are farmers who work the generally small fields that cover the plain. Most of them produce wheat, which grows well in the relatively dry climate. The forests that once blanketed the plain were cut down thousands of years ago, and now the only trees that survive are those surrounding temples and those planted as windbreaks.

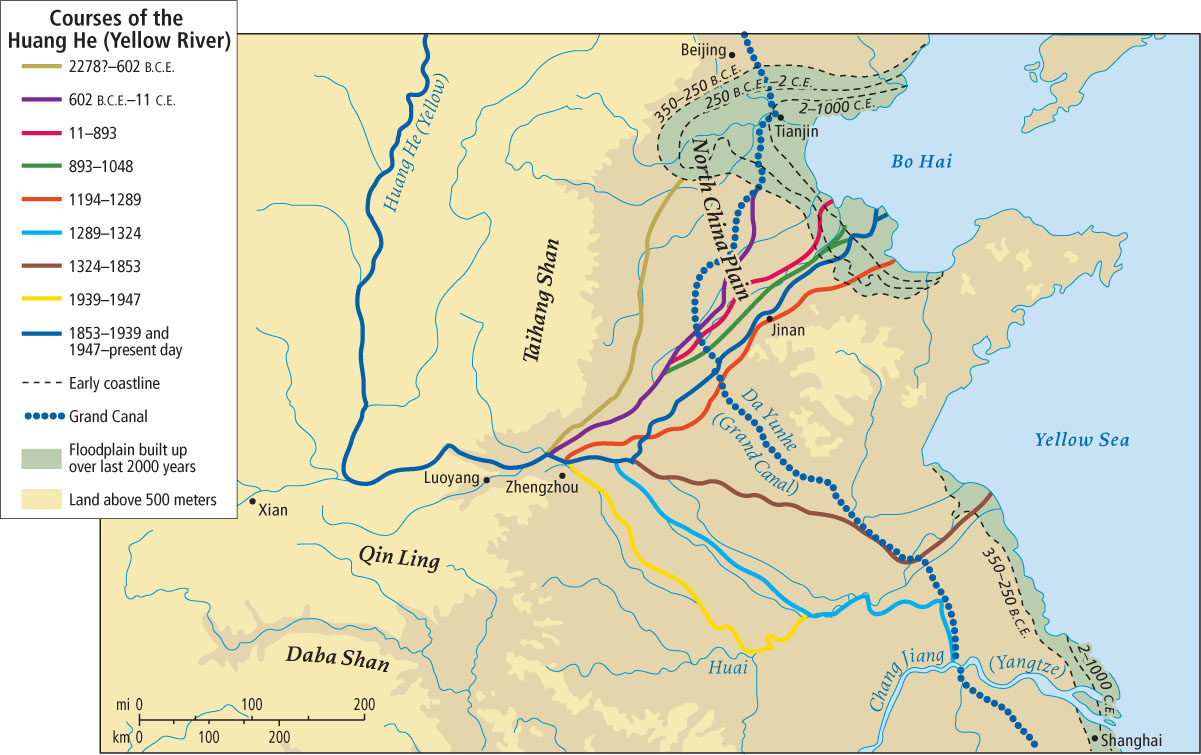

The Huang He, the river that created the North China Plain, remains the plain’s most important physical feature, serving as a major transportation artery and a source of irrigation water, but also producing disastrous floods. After the river descends from the Loess Plateau, its speed slows dramatically on the flat surface of the plain, and its load of sediment begins to settle out. This sediment raises the level of the riverbed year after year until, in some places, it lies higher than the plain. Occasionally, during the spring surge, the river breaks out of the levees that have been built to control it and rushes across the surrounding densely occupied plain. The spring surge has forced the Huang He to cut many new channels over time (Figure 9.34), and it also endows the plain with a new layer of fertile soil as much as a yard (a meter) thick each year. Because it both enriches and destroys, the river is referred to as both the Mother of China and China’s Sorrow.

China’s Far Northeast

The northeastern corner of China inland of the Korean peninsula, historically known as Manchuria, was long considered a peripheral region, partly because of its location and partly because of its harsh climate. The winters are long and bitterly cold, the summers short and hot. The growing season is less than 120 days. Nonetheless, China’s Far Northeast subregion found an important niche in the country’s economy in the post-revolution 1950s, when its rich mineral resources—oil, coal, gas, gold, copper, lead, and zinc—made possible major industrialization, and its fertile state farms began to produce wheat, corn, soybeans, sunflowers (for oil), and beets. The Far Northeast was known for its steel (20 percent of the national output), coal, and petroleum production (it is still the country’s leading oil-producing province), and for its “iron man” workers who labored heroically for the revolution in return for meager wages and barracks-like housing. The Heilong Jiang (Amur River), which runs more than 1000 miles (1600 kilometers) along the border between Russia and China, became a conduit for increasing trade with Russia, other parts of China, and Japan. The Far Northeast was slated to make the entire country industrially self-sufficient.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, when Communist Party policy introduced a market economy, the geographic focus of development shifted to Guangdong Province in Southern China, to the international banking center of Hong Kong (then a British colony), to the Chang Jiang (Yangtze) delta and Shanghai, and even to Xinjiang in far western China. By the 1990s, China’s far northeast was considered a rust belt. Its outdated industrial facilities are being dismantled to make way for new factories that can compete in the global economy. Its millions of laid-off workers are being evicted from slum dwellings that will be replaced with upscale apartments for more select, highly skilled technology workers who are being enticed from elsewhere in the country. The northernmost province Heilongjiang is not, unlike most parts of China, increasing its population. To raise its global profile, the province’s largest city, Harbin, arranges a 1-month ice festival every winter that has thousands of ice sculptures and draws both domestic and international tourists.

Much of the revitalization is concentrated in cities on the coast, such as Dalian, and is financed by nearby Korean and Japanese firms that train young people to do telephone sales, information technology (IT), or manufacturing work. The Japanese occupied China’s Far Northeast between 1932 and 1945. Their regime is remembered as brutal, but they were the first to introduce industrial development to the region. Now, because the Japanese are bringing investment cash and a chance for economic renewal, they are welcomed.

Beijing and Tianjin

There are 12 million residents in the urban core of Beijing, China’s capital city, and more than 20 million in its metropolitan region. Beijing lies at the northern edge of the North China Plain. It is the administrative headquarters of the People’s Republic of China and has several of the nation’s most prestigious universities. Because Beijing is not located right at the coast, the nearby port city of Tianjin, an industrial and transportation center, is important for the regional economy. The selection of Beijing as host of the 2008 Summer Olympics established the city—and China—as a global leader in the modern era.

Beijing was once a grand imperial city full of architectural masterpieces—notably the Forbidden City, the former imperial headquarters—but much of its character was lost under the Communists, who tore down many monuments. Today, in the context of China’s acceptance of capitalism, much of Beijing is being reconstructed, this time as a center for international commerce, with new neighborhoods of high-rise apartments, office towers, and hotels replacing Communist-era apartment blocks and older neighborhoods of nineteenth-century, tile-roofed, extended-family homes.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Loess Plateau has rich, thick soil, but agricultural practices have resulted in soil erosion, gullies within the landscape, and reduced agricultural productivity.

The Loess Plateau has rich, thick soil, but agricultural practices have resulted in soil erosion, gullies within the landscape, and reduced agricultural productivity. After flowing through the Loess Plateau, the Huang He remains China’s most important physical feature, serving as a major transportation artery and a source of irrigation water—as well as a source of disastrous floods and a conveyor or depositor of sediment.

After flowing through the Loess Plateau, the Huang He remains China’s most important physical feature, serving as a major transportation artery and a source of irrigation water—as well as a source of disastrous floods and a conveyor or depositor of sediment. China’s northeast is home to Beijing, the nation’s capital, and the nearby industrial and port city of Tianjin.

China’s northeast is home to Beijing, the nation’s capital, and the nearby industrial and port city of Tianjin.