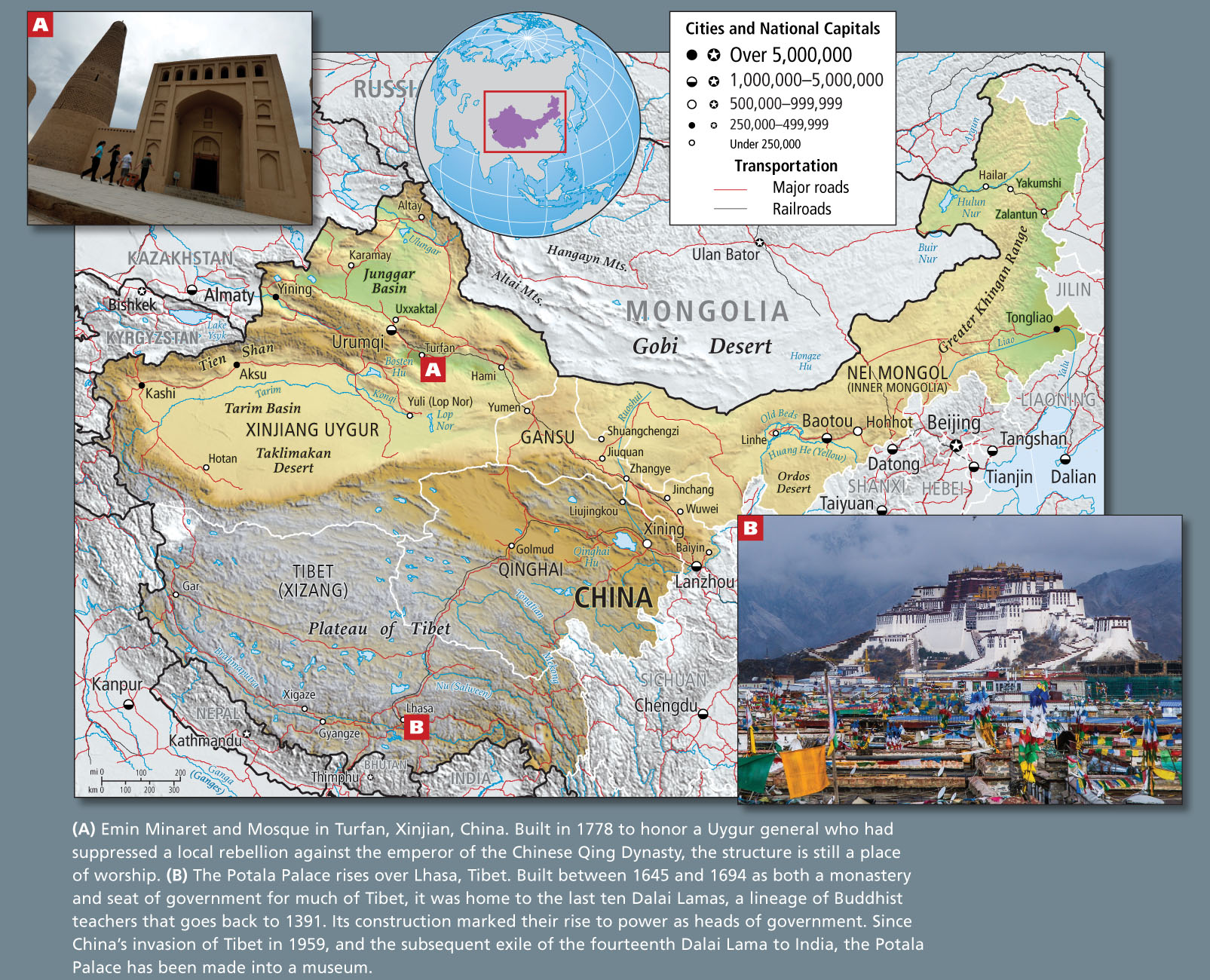

Far West and North China

The Far West and North subregion of China (Figure 9.39) once occupied a central role in the global economic system. Traders carried Chinese and Central Asian products such as silks, rugs, spices and herbs, and ceramics over the Silk Road to Europe, where they exchanged them for gold and silver. Today, the subregion is recovering some of its ancient economic vitality, but it is not yet clear who will profit from the changes.

Despite its trading past, this large interior zone has historically been considered backward by the rulers of eastern China because of its dry, cold climate, vast grasslands, long history of nomadic herding, and—in the lands of the Uygurs and Kazakhs—its persistent adherence to Islam. Settlements are widely dispersed, and most agriculture requires irrigation. Three of the subregion’s four political divisions have been designated autonomous regions (not provinces) because of the high percentage of ethnic minority populations there (Nei Mongol, also called Inner Mongolia, is perhaps the best known of these autonomous regions), but their people do not enjoy real autonomy. The central government in Beijing retains control over political and economic policies because it sees this subregion as crucial to China’s future: it has energy and other resources for industrial development, it is close to the emerging oil-rich economies of Central Asia and Russia, and it affords a place to resettle some of China’s surplus population.

Xinjiang

The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern China is historically and physically part of Central Asia. Yet it is the largest of China’s political divisions, accounting for one-sixth of China’s territory.

yurts (or gers) round, heavy, felt tents stretched over collapsible willow lattice frames used by nomadic herders in northwestern China, Mongolia, and Central Asia

qanats underground tunnels, built by ancient cultures and still used today, that carry groundwater for irrigation in dry regions

In Xinjiang today, the local and the global, the very traditional and the very modern, confront each other daily. Herdspeople still living in yurts and gers dwell under high-voltage electric wires that supply new oil rigs. Tajik women weave traditional rugs that are sold to merchants who fly from faraway developed countries to the ancient trading city of Kashi (Kashgar) for the Sunday market (see Figure 9.28). With the breakup of the Soviet Union, citizens of the new republics of Central Asia are eager to revive their trading heritage, and they have oil and gas to sell. China is welcoming them and attracting outside investors from Europe and the Americas by establishing ETDZs in cities such as Kashi and Urumqi. As discussed above, the Uygur and other ethnic leaders of Xinjiang are wary of Beijing, fearing that the central government’s singular intent is to exploit Xinjiang’s oil and gas resources and to appropriate land for the resettling of eastern China’s excess population.

The Plateau of Tibet

Situated in far western China, the Plateau of Tibet is the traditional home of the Tibetan people. Administratively, it includes the Xizang Autonomous Region and Qinghai Province. Tibet (Xizang) and Qinghai lie an average of 13,000 feet (4000 meters) and 10,000 feet (3000 meters) above sea level, respectively. They are surrounded by mountains that soar thousands of feet higher. They have cold, dry climates (late June can feel like March does on the American Great Plains) because of their high elevation and because the Himalayas to the south block warm, wet air from moving in from the Indian Ocean. Across the plateau, but especially along the northern foothills of the Himalayas, snowmelt and rainfall are sufficient to support a short growing season for barley and vegetables such as peas and broad beans. Meltwater from Himalayan snow and glaciers forms the headwaters of some major rivers: the Indus, Ganga (Ganges), and Brahmaputra begin in the western Himalayas, and the Nu (Salween), Irrawaddy, Mekong, Chang Jiang, and Huang He all begin along the eastern reaches of the Plateau of Tibet. Many of the larger settlements in Tibet are located along the valley of the Brahmaputra (called Yarlung Zangbo in Chinese) in the southern part of the province.

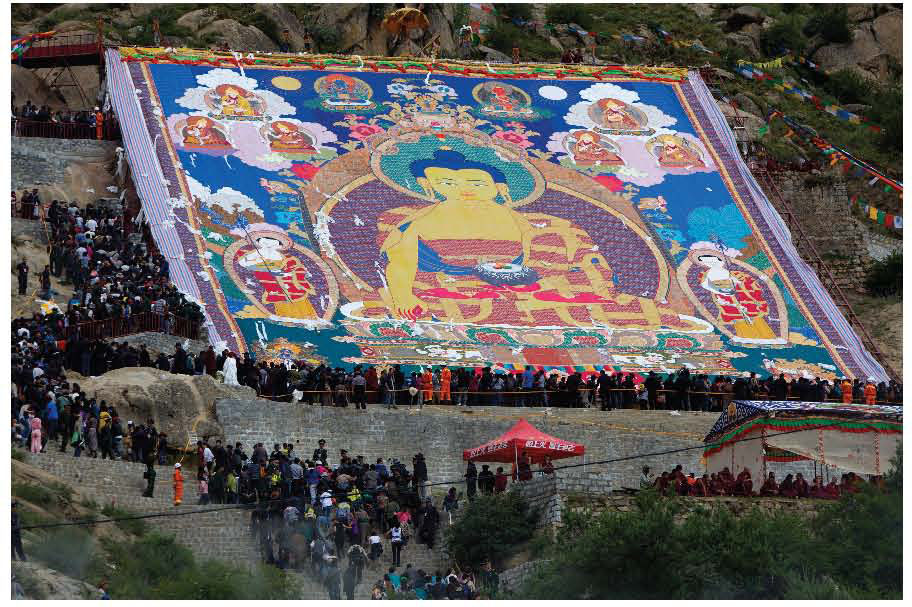

Traditionally, the economies of Tibet and Qinghai have been based on the raising of grazing animals. The main draft animal is the yak, which also provides meat, milk, butter, cheese, hides, and fiber, as well as dung and butterfat for fuel and light. Other animals of economic importance are sheep, horses, donkeys, cattle, and dogs. Animal husbandry on the sparse grasses of the plateau has required a mobile way of life so that the animals can be taken to the best available grasses at different times of the year. For several decades, though, the Chinese government has pressured Tibetan herdspeople to settle in permanent locations so that their wealth can be taxed, their children schooled, their sick cared for, and their dissidents curtailed. Still, throughout the plateau, many native (non-Han) peoples continue to live mobile yet solitary lifestyles, as they have for centuries, occasionally adopting some aspects of modern life and adapting to its restrictions. The political history of the Tibetan minority in China and suppression of Tibetan culture (Figure 9.41; see also Figure 9.39B) are discussed.  218. CHINA CLAIMS WORLD’S LARGEST DOMESTIC TOURISM MARKET

218. CHINA CLAIMS WORLD’S LARGEST DOMESTIC TOURISM MARKET

THINGS TO REMEMBER

China’s Far West and North subregion has historically been considered backward by the rulers of eastern China because of its dry, cold climate; its vast grasslands; its long history of nomadic herding; and its persistent adherence to Islam and Tibetan Buddhism.

China’s Far West and North subregion has historically been considered backward by the rulers of eastern China because of its dry, cold climate; its vast grasslands; its long history of nomadic herding; and its persistent adherence to Islam and Tibetan Buddhism. Three of the subregion’s four political divisions have been designated autonomous regions because of the high percentage of ethnic minority populations there.

Three of the subregion’s four political divisions have been designated autonomous regions because of the high percentage of ethnic minority populations there. The central government in Beijing retains control over political and economic policies because the subregion has energy and other resources for industrial development; it is close to the emerging oil-rich economies of Central Asia and Russia; and it affords a place to resettle some of China’s surplus population.

The central government in Beijing retains control over political and economic policies because the subregion has energy and other resources for industrial development; it is close to the emerging oil-rich economies of Central Asia and Russia; and it affords a place to resettle some of China’s surplus population.