Mongolia

The present country of Mongolia (Figure 9.42) is the north-central part of what was once a much larger cultural area in eastern Central Asia known by the same name. Between 1206 and 1370, the Mongols, under Genghis Khan and his grandson Kublai Khan, created the largest-ever land-based empire, stretching from the eastern coast of China to central Europe, including parts of modern Russia and Iran. While in control of China, the Mongols improved the status of farmers, merchants, scientists, and engineers; fostered international trade; and broke the control of traditional elites by abolishing their automatic access to privilege. They refined the manufacture of textiles, jewelry, and blue and white porcelain, and trade in these wares flourished along the Silk Road. Although the Mongols brought many important reforms to China, they also practiced authoritarian rule and discrimination against ethnic Chinese. Deposed by the Chinese in 1366, the Mongols retreated to the north; over the next 300 years, their control of territory in Central Asia and Europe dwindled. Eventually, the southern part of Mongolia (somewhat confusingly called Inner Mongolia) became part of China.

The Mongolian Plateau lies in the heart of Central Asia, directly north of China and south of Siberia. It is high, cold, and dry, with an extreme continental climate. The physical geography of Mongolia can be broken down into four major zones. In the far southeast and extending across the border into China is the Gobi Desert—actually a very dry grassland that grades into true desert in particularly dry years or where it is overgrazed. It is likely to be especially prone to increased aridity with global climate change. To the west and northwest of the Gobi is a huge rolling, somewhat moister grassland. The remaining two zones are Mongolia’s two primary mountain ranges: the forested Hangayn Nuruu, in north-central Mongolia, and the grass- and shrub-covered Altai Mountains, which sweep around to the west and south and into the Gobi Desert (see the Figure 9.42 map).

With just 2.9 million people, Mongolia occupies a territory so large that its average population density is one of the lowest on Earth, at 4 people per square mile (1.5 per square kilometer). For thousands of years, the economy has been based on the nomadic herding of sheep, goats, camels, horses, and yaks. Nomadic pastoralism, one of the most complex agricultural traditions in the world, dates at least as far back as the domestication of plants (8000 to 10,000 years). Nomadic pastoralists must understand the intricate biological requirements of the animals they breed, and they must also know the ecology and seasonal cycles of the landscapes they traverse with their herds.

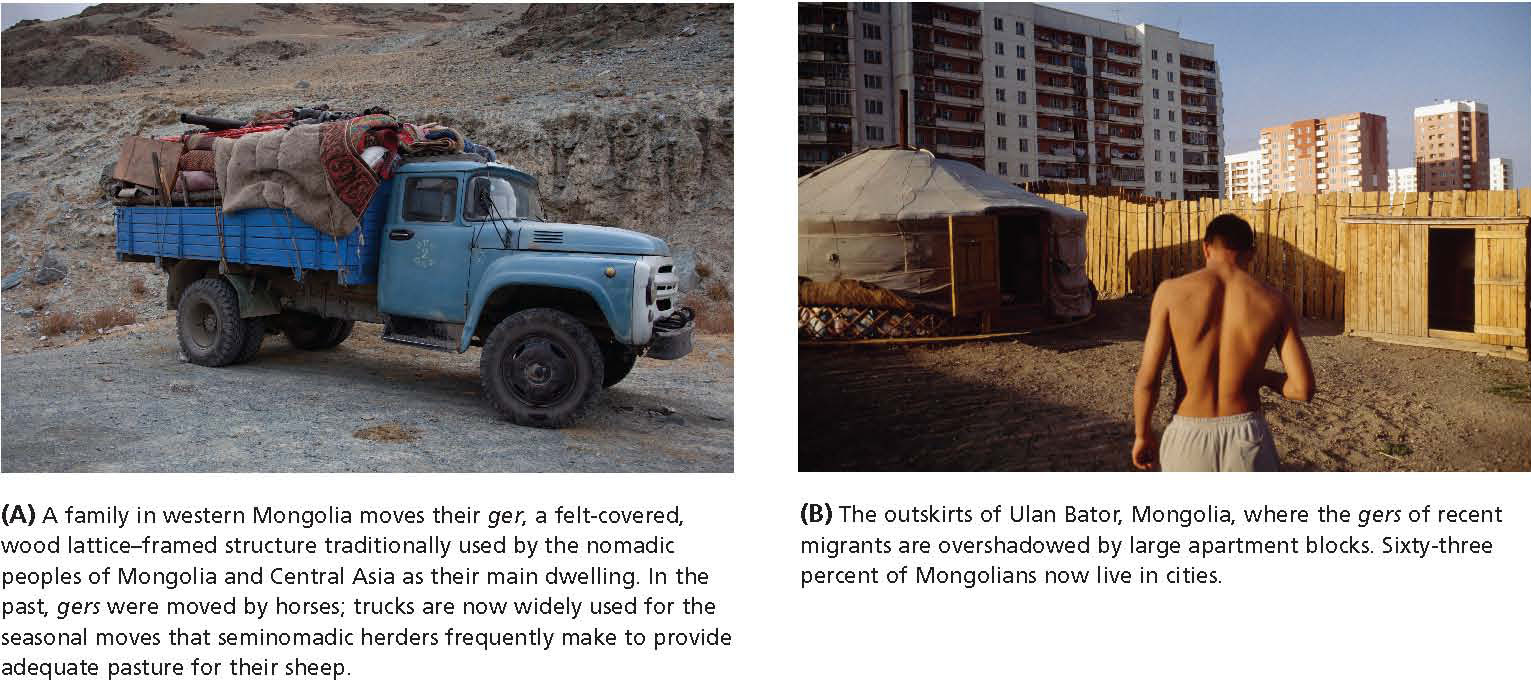

Today, only 37 percent of Mongolians are still engaged in rural activities, often related to this traditional lifestyle (Figure 9.43A; see also Figure 9.42A). The other 63 percent now live in cities, primarily the capital, Ulan Bator (see Figure 9.43B). Urban workers are employed in a wide range of services and in industries related to the processing of minerals from Mongolia’s mines and animal products such as hides, fur, and wool. In the 1990s, Mongolia’s transition from Communist central planning to a market economy was complicated by an economic recession that forced some people who were working in urban jobs to return to the countryside. As we shall see, the world recession that began in 2008 has had an even worse effect on work and workers in Mongolia.

The Communist Era in Mongolia

Influenced by the Russian Revolution of 1917, and after considerable internal turmoil, Mongolia first declared independence from China in 1921; three years later it became a communist republic under the Soviet sphere of influence. From 1924 to 1989, Mongolia sought guidance from Soviet advisers and technicians. They helped set up a system of central planning that reorganized the nomadic pastoral economy according to socialist policies, but did so without drastically disrupting traditional lifeways. Rural households of extended families became economic collectives. Some households continued to herd and breed animals, others engaged in sedentary livestock production, and still others farmed crops. During this time, Mongolia also began to industrialize and urbanize. By 1985, nomadic herding and forestry were declining, accounting for less than 18 percent of the Mongolian GDP and less than 30 percent of the labor force, whereas employment in mining, industry, and services accounted for about half of the GDP and a third of the labor force.

During this period, the Mongolian economy was supported by the Soviets, who subsidized a wide array of social services. By 1989, there was nearly universal education through middle school, and adult literacy had reached 93 percent. Health care was available to all, and life expectancy had risen dramatically. The previously high infant mortality rates dropped, and then fertility decreased.

Post-Communist Economic Issues

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, coupled with several natural disasters and lower world prices for the minerals that Mongolia produces, led to immediate budget problems and declines in economic growth, human well-being, and social order. The Soviet advisers left without training Mongolian replacements to run the economy. Layoffs and factory closings caused a severe decline in living standards. By 2003, about one-third of the population lived in poverty.

Some signs of a better future, however, were emerging. Mongolia’s new membership in the WTO promised to bring increased international attention and development assistance, and private foreign investors took an interest in the country, especially in its minerals. China, with its booming economy just to the south, has been particularly interested in Mongolia’s minerals, especially copper and gold. Mongolia’s human development report for 2007 sounded glowingly optimistic, noting improvements in health, education, and income in all provinces.

This period of increasing affluence was stopped dead in 2008 by the global recession, which was much more severe in Mongolia than in any of the other East Asian countries, primarily because Mongolia depended on the export of raw materials—fleece from sheep and goats, and mined minerals—for which market prices dropped precipitously. But also Mongolians suffered from a credit bubble, smaller than but similar to the housing bubble in the United States, eventually leading to widespread defaults on consumer products.

The dire financial crisis of Mongolian working people is being written into their fragile grassland landscapes. In 2009, National Public Radio reporter Louisa Lim told of frantic unemployed men and their families, an estimated 100,000 people, who had begun to mine for gold in the rolling hills south of Ulan Bator. The dry slopes were stripped of grass and honeycombed with pits the size of graves. The dirt was sifted in mountain streams for the tiny dots of gold that could bring an impoverished family enough to eat. Scarce water sources were wasted, the grasslands decimated, and the land opened up for horrendous wind erosion. And now, since larger industrial mining companies are joining the fray, the environmental damage is escalating, while at the same time bringing renewed, post-recession economic growth. But Mongolia is heavily dependent on raw material exports to China and energy imports from Russia, which means that recent economic shocks may be repeated in the future. [Source: National Public Radio and the Mongolia Human Development Report. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

In the last decade, Mongolia invested heavily in IT. Today, there is an extensive 3G network and many homes in the capital have Internet. Most people, including nomads, have at least one cell phone, far out in the steppe. [Source: Pappano, Laura (2013, September 15). The Boy Genius of Ulan Bator. New York Times Magazine, p. 52.]

Gender Roles in Mongolia

Traditionally, Mongolian women enjoyed a status approximately equal to that of men, but outside forces, such as Tibetan Buddhism in the sixteenth century and Chinese rule in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, eroded their status. The Communist era restored, or even enhanced, egalitarian gender attitudes. The daily work of women herders was valued by the government, and like their husbands, women were eligible for old-age pensions. A woman could leave an unsuccessful marriage because the government provided support for her and her children. A few women became teachers, judges, and party officials, and soon women were represented in institutions of higher education.

In today’s modern nomadic pastoral economy, as in the past, women usually choose which stock to breed, tend the mother animals and their young, preserve meat and milk, and produce many essentials from animal hides and hair. Women provide the materials for the construction of gers and also dye and weave beautiful furnishings for the interiors. Both boys and girls are taught to ride horses at an early age, and both help with the herding. As they mature, women become more responsible than men for the routines of daily life in the home. Men engage primarily in pasturing the herds and arranging the marketing of the animals and animal products. Men also perform other tasks—such as the occasional planting of barley and wheat—that are carried out beyond the home compound.

When the Soviets left and the economy collapsed, women lost some of the status they had enjoyed, but they are now regaining legal protections and access to education, jobs, health care, housing, and credit. And women entrepreneurs are emerging. As in so many other countries that are moving from communism to a market economy, the informal economy—in which women are particularly active—has been an essential component of the Mongolian economic transition.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Sustainable management of Mongolia’s sparse but valuable natural resources, such as minerals and grassland used for nomadic pastoralism, has proven to be difficult.

Sustainable management of Mongolia’s sparse but valuable natural resources, such as minerals and grassland used for nomadic pastoralism, has proven to be difficult. Mongolia continues to move toward a better-functioning market economy despite the recent economic downturn.

Mongolia continues to move toward a better-functioning market economy despite the recent economic downturn. Mongolia has a better-than-average record on gender equality both for the region and globally.

Mongolia has a better-than-average record on gender equality both for the region and globally.