Japan

Japan consists of a chain of four main islands and hundreds of smaller ones (Figure 9.46). Prone to severe earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons, and so mountainous that only 18 percent of its land can be cultivated, the Japanese archipelago might seem an unlikely place to find 128 million people living in affluent comfort. (Typhoon Wipha devastated Izu Oshima island, October 16, 2013.) Yet its citizens have learned to cope with these limitations and have made the most of crowded conditions in cities and countryside alike.

A Wide Geographic Spectrum

Modern Japanese populations are descended from migrants from the Asian mainland, the Korean Peninsula, and the Pacific Islands. Ideas and material culture imported from these places include Buddhism, Confucian bureaucratic organization, architecture, the Chinese system of writing, the arts, and agricultural technology.

Japan stretches over a range of latitudes roughly comparable to that between Canada’s province of Nova Scotia and the Georgia coast (and even as far south as the Florida Keys, if one counts Japan’s tiny, southernmost islands). Although half a world away, it has a similar range of climates to the North American Eastern Seaboard. The climate is cool on the far northern island of Hokkaido; temperate on the islands of Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku; and tropical in the southern Ryukyu Islands. Despite the moderating effect of the surrounding oceans, the great seasonal climate shifts of nearby continental East Asia give Japan a more extreme seasonal variation in temperature than it would have if it lay farther out to sea.

Honshu, the largest and most densely populated of Japan’s islands, has the most mountains and forests. Because it has gained access to forest products from Southeast Asia and other parts of the world, Japan has been able to keep much of its own forestland in reserves. Today, the interior mountains of Honshu (and Hokkaido) remain largely forested, although many of the slopes are planted with a monoculture of sugi (Japanese cedar) that is harvested commercially as building material. The few flat lowlands and coastal areas of northern and southern Honshu were once intensively cultivated and supported a dense rural population. Today, industrial cities fill many of these lowlands, especially in the south. Tokyo–Yokohama is the largest urban agglomeration in the world, with approximately 34 million people (27 percent of Japan’s total). It lies on the east-central coast of Honshu on the Kanto Plain, Japan’s largest flatland. Kobe–Osaka–Kyoto, Japan’s second-largest metropolitan area, with 17 million people, is one of several major urban areas located on the flatlands that ring the Inland Sea.

Japan’s other three main islands are Hokkaido, the least populated island, referred to as Japan’s northern frontier, and Kyushu and Shikoku, two smaller southern islands. The northern slopes of Kyushu and Shikoku, facing the Inland Sea (see the Figure 9.46 map), have narrow strips of land that is put to agricultural, industrial, and urban uses. The southern slopes are more rural and agricultural. Off Kyushu’s southern tip, the very small, mountainous Ryukyu Islands stretch out in a 650-mile (1000-kilometer) chain, reaching almost to Taiwan. Although many areas are densely settled and are important for tourism and specialty agriculture, such as the growing of pineapples, the Ryukyu Islands are considered a poor, rural backwater of the four big islands.

The Challenge of Living Well on Limited Resources

Japan has among the highest ratios of people to farmland in the world: more than 7000 people depend on each square mile (more than 2700 per square kilometer) of cultivated (arable) land. Thus, Japanese agriculture relies heavily on high-yield varieties of rice and other crops, as well as on irrigation, fertilization, and mechanization. Because flat land is scarce, Japanese farmers have had to make efficient use of hill slopes by planting tea bushes and orchards and by terracing for rice paddies.

Although subsistence ways of life play a large part in Japanese national identity, today only 4 percent of the population fish or farm for a living. Japanese farms are highly productive in terms of output per acre; however, their food is some of the most expensive in the world. A 2-pound (1-kilogram) bag of rice costs U.S.$8, more than twice the price in New York City. The seas surrounding Japan, where warm and cold ocean currents mix, are an especially important source of food for the country, especially considering the limited amount of farmland. There are some 4000 coastal fishing villages and tens of thousands of small craft that work these waters and bring home great quantities of tuna, halibut, mackerel, salmon, and other fish. In addition, a large aquaculture industry produces oysters, seaweed, and other foods in shallow bays, and freshwater fish in artificial ponds.

food self-sufficiency the ability of an area, such as a country, to produce food domestically to meet the needs of its people

Japan’s Culture of Contrasts

Perhaps more than any other country in the world, Japan is renowned for its ability to confound foreigners. Here, in an attempt to penetrate some of Japan’s cultural complexity, we look at a few of its unique cultural phenomena.

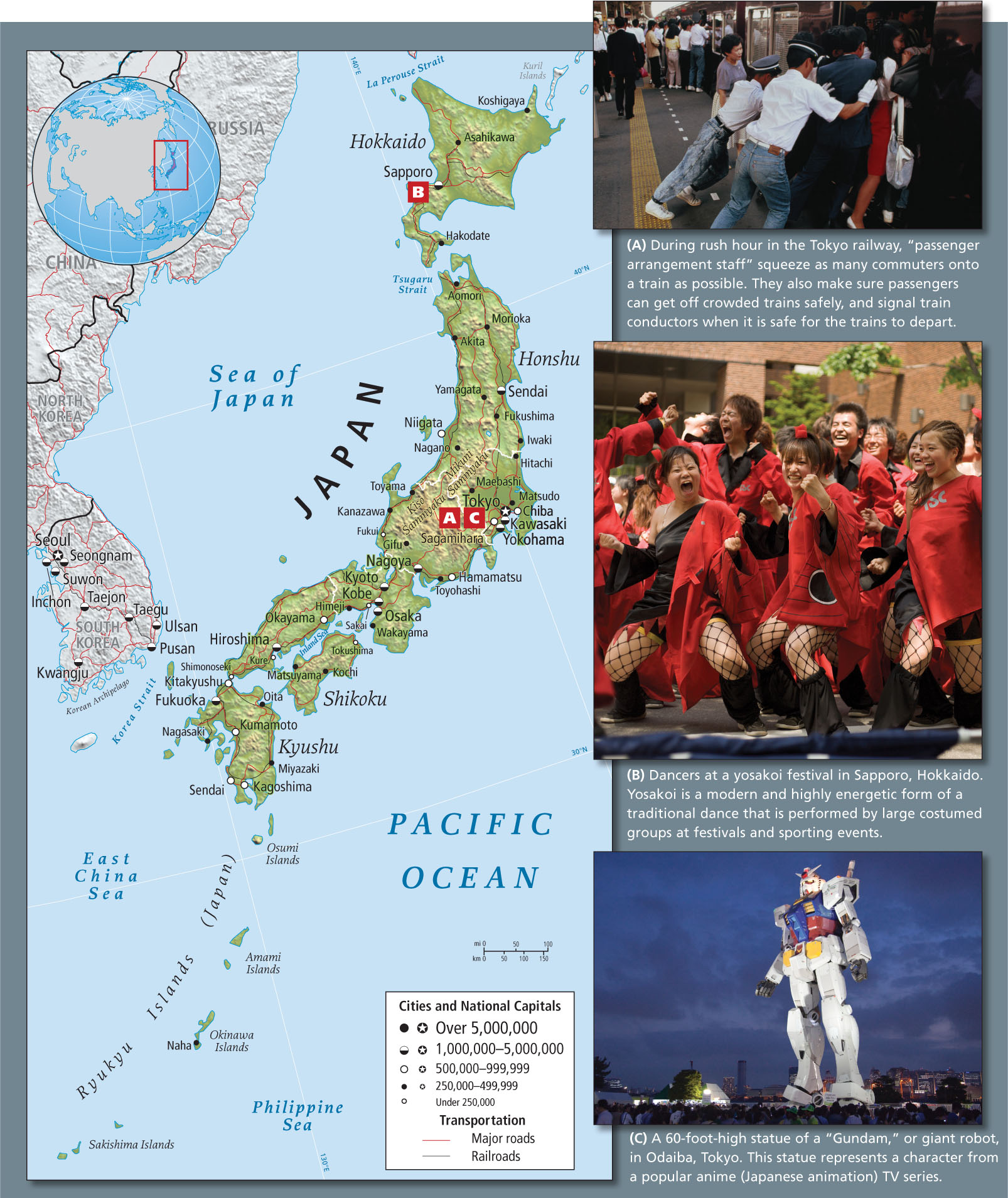

Japan has combined its long-standing traditions with customs from around the world, resulting in unique cultural contrasts and apparent contradictions. We see the mix in many ways: in the kinds of clothes people wear, in the foods they eat, in the music they listen to, in the sports they enjoy, and in the cultural impact they have abroad. Thus, among other contrasts, Japan is a land of kimonos and blue jeans, sushi and hamburgers, the koto (a traditional stringed instrument) and rap music, sumo wrestling and baseball. Japanese couples who marry in traditional wedding kimonos often change their clothing after the ceremony to a Western-style tuxedo and a white bridal dress for the reception. Japanese culture is a blend of modern influences and respect for tradition and authority (see Figure 9.46).

There is often a distinction in Japanese life between what is displayed on the outside, omote, and what is private on the inside, ura. The former often protects the latter, as in the contrasts between omote-ji, the outer layer of cloth in a kimono, and ura-ji, the layer closest to the skin. This cultural attitude is also expressed geographically. Omote-Nippon, the urban-industrial eastern (Pacific Ocean) side of Japan, trades with the world, while Ura-Nippon is the more traditional and secluded western (Sea of Japan) side of the country.

Working in Japan

Japan’s distinctive culture is in part reflected in the traditional working lives of its people, as well as in their attitude toward the outsiders who perform many of the country’s most menial jobs.

The Japanese are well known for their hard work, high-quality output, and devotion to their jobs. Since before World War II, the norm in Japan has been that an employer provides lifetime employment, regular paid vacations, a pension upon retirement, and often, subsidized housing and perhaps even a graveyard for employees. Job-hopping is considered reprehensible. Personnel management instills loyalty to the employer. The prototypical Japanese corporate employee is a “salaryman”—a male, usually with a family he rarely sees, who lives to work. Individualism is regarded as selfish, and making innovative suggestions is discouraged. Employees who have good ideas may not present them for several years, or may give credit to someone else. The Japanese language does not even have a word for “entrepreneur”; only recently has the English term become a buzzword in Japanese.

This norm is now receding in the face of larger economic and social changes. During the recession of the 1990s and since, many companies had to reduce their workforces and cut back employee benefits. Moreover, some younger male and female graduates in business and technological fields have turned away from the old pattern in favor of the freedoms of temporary employment. Although they may settle for a lower standard of living and give up job-related benefits, women enjoy less gender discrimination in temporary or contract jobs, and temporary workers do not feel compelled to acquiesce to their superiors or to work overtime. This freelance approach to work allows them time to start their own businesses and perhaps spend more time with their families. However, whether by choice or necessity, accepting a temporary or part-time job is risky. The old loyalty system makes it difficult to find a new job, and firms worried about industrial espionage are often unwilling to hire someone who has worked for a competing company.

Foreign Workers

Foreign workers from poor countries come to Japan as guest workers to take some of the hard, dirty, dangerous, and low-paying jobs that today’s Japanese workers avoid. They come from places such as China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Iran, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, and Africa. Some Latin American immigrants are descendants of Japanese people who went abroad in search of work some generations ago, when Japan was a poorer country. Foreign men often work in construction, in factories, and as dishwashers in restaurants; women work as hotel maids, as cleaners, and in other low-status jobs. Many foreign women are also employed as hostesses in bars and as sex workers. The recruitment of women for sex work has become a controversial issue because unscrupulous “agents” have been known to force women into sex-industry jobs after promising them other kinds of work. As the recession increased unemployment, some foreign workers, who make up only 1.7 percent of the Japanese population, have been paid by the Japanese government to go back home. This may be a short-sighted policy, as the Japanese workforce needs to expand in order to remain productive in the future.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Japan has among the highest ratios of people to farmland in the world: more than 7000 people depend on each square mile (more than 2700 per square kilometer) of cultivated land. Its food self-sufficiency level is very low from an international perspective.

Japan has among the highest ratios of people to farmland in the world: more than 7000 people depend on each square mile (more than 2700 per square kilometer) of cultivated land. Its food self-sufficiency level is very low from an international perspective. Japan has a culture of contrasts and complexities: long-standing indigenous customs and traditions mixed with aspects of global culture—in the home, in urban spaces, and in the workplace.

Japan has a culture of contrasts and complexities: long-standing indigenous customs and traditions mixed with aspects of global culture—in the home, in urban spaces, and in the workplace.