Physical Patterns

A quick look at the regional map of East Asia (see Figure 9.1) reveals that the topography here is perhaps the most rugged in the world. East Asia’s varied climates result from the meeting of huge warm and cool air masses and the dynamic interaction between land and oceans. The region’s large human population has affected the variety of ecosystems that have evolved there over the millennia and that still contain many important and unique habitats.

Landforms

The complex topography of East Asia is partially the result of the slow-motion collision of the Indian subcontinent with the southern edge of Eurasia over the past 60 million years. This tremendous force created the Himalayas and lifted up the Plateau of Tibet (see Figure 9.1A, also depicted in gray and gold in the Figure 9.1 map), which can be considered the highest of four descending steps that define the landforms of mainland East Asia, moving roughly west to east.

The second step down from the Himalayas is a broad arc of basins, plateaus, and low mountain ranges (depicted in yellowish tan in the Figure 9.1 map). These landforms include the broad, rolling highland grasslands and deep, dry basins and deserts of western China (such as the Taklimakan Desert) and Mongolia (see Figure 9.1B), as well as the Sichuan Basin and the rugged Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south, which is dominated by a system of deeply folded mountains and valleys that bend south through the Southeast Asian peninsula.

The third step, directly east of this upland zone, consists mainly of broad coastal plains and the deltas of China’s great rivers (shown in shades of green in the map in Figure 9.1). Starting from the south, this step is defined by three large lowland river basins: the Zhu Jiang (Pearl River) basin, the massive Chang Jiang basin (see Figure 9.1C), and the lowland basin of the Huang He on the North China Plain. Each of these rivers has a large delta. Despite the deltas being subject to periodic flooding, they have long been used for agriculture; but now coastal cities have spread into these deltas, filling in wetlands. Each is now a zone of dense population and industrialization (see Figure 9.17). Low mountains and hills (shown in light brown) separate these river basins. China’s Far Northeast and the Korean Peninsula are also part of this third step.

The fourth step consists of the continental shelf, covered by the waters of the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea. Numerous islands—including Hong Kong, Hainan, and Taiwan—are anchored on this continental shelf; all are part of the Asian landmass (see Figure 9.1D).

tsunami a large sea wave caused by an earthquake

The East Asian landmass has few flat portions, and most flat land is either very dry or very cold. Consequently, the large numbers of people who occupy the region have had to be particularly inventive in creating spaces for agriculture. They have cleared and terraced entire mountain ranges, until recently using only simple hand tools (see Figure 9.5A). They have irrigated drylands with water from melted snow, drained wetlands using elaborate levees and dams, and applied their complex knowledge of horticulture and animal husbandry to help plants and animals flourish in difficult conditions.

Climate

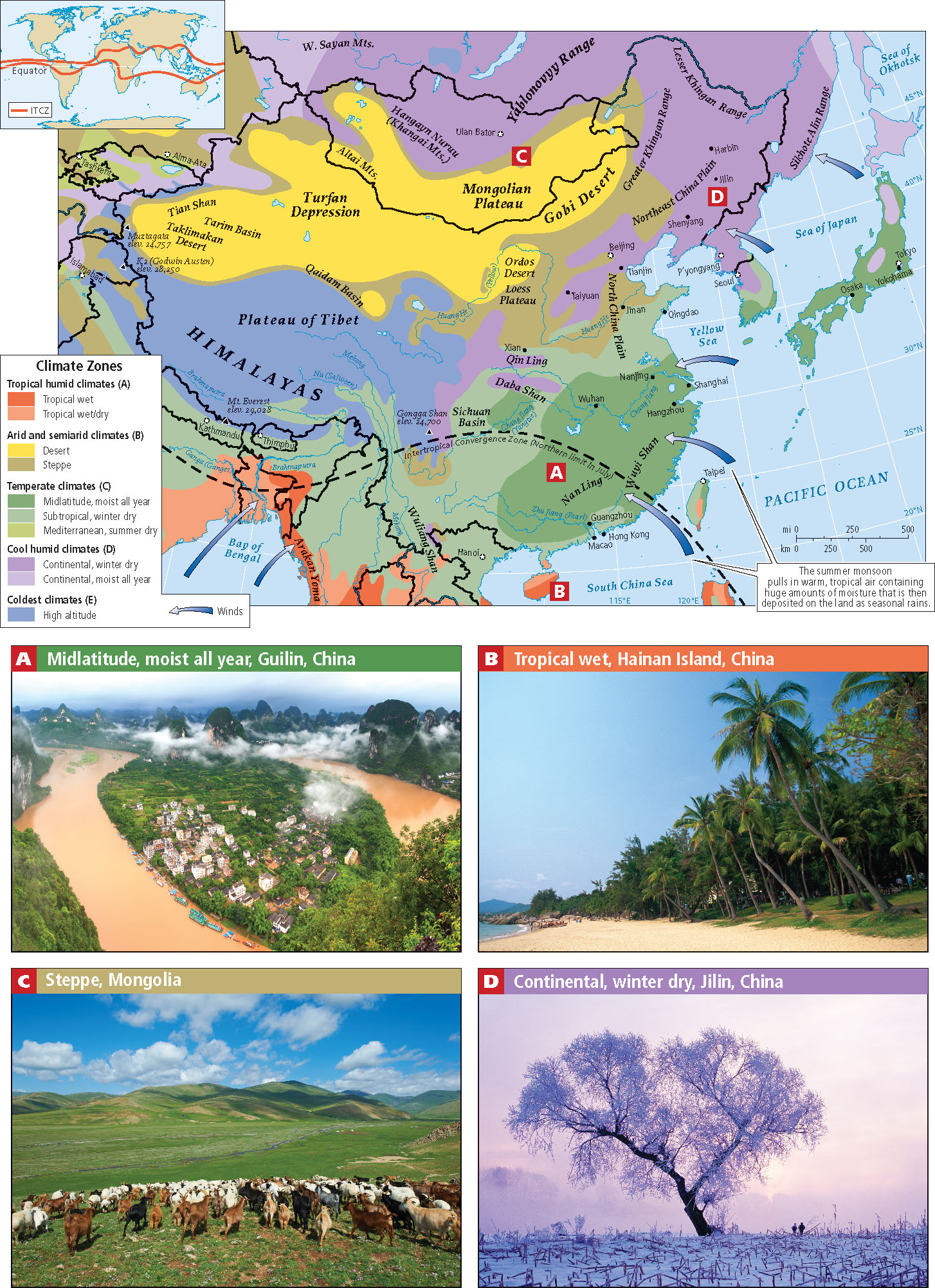

East Asia has two principal contrasting climate zones, shown in the Figure 9.4 map: the dry interior west and the wet (monsoon) east. Recall from Chapter 8 that the term monsoon refers to the seasonal reversal of surface winds that flow from the Eurasian continent to the surrounding oceans during winter and from the oceans inland during summer.

The Dry Interior

Because land heats up and cools off more rapidly than water does, the interiors of large landmasses in the midlatitudes tend to be intensely cold in winter and extremely hot in summer. Western East Asia, roughly corresponding to the first two topographic steps described above, is an extreme example of such a midlatitude continental climate because it is very dry. In fact, this area is farther away from an ocean than any other place on Earth’s surface (also known as the “pole of inaccessibility”). With little vegetation or cloud cover to retain the warmth of the sun after nightfall, summer daytime and nighttime temperatures may vary by as much as 100°F (55°C).

Grasslands and deserts of several types cover most of the land in this dry region (see Figure 9.4C). Only scattered forests grow on the few relatively well-watered mountain slopes and in protected valleys supplied with water by snowmelt. In all of East Asia, humans and their impacts are least conspicuous in the large, uninhabited portions of the deserts of Tibet (Xizang), the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, and the Mongolian Plateau.

The Monsoon East

The monsoon climates of the east are influenced by the extremely cold conditions of the huge Eurasian landmass in the winter and the warm temperatures of the surrounding seas and oceans in the summer. During the dry winter monsoon, descending frigid air sweeps south and east through East Asia, producing long, bitter winters on the Mongolian Plateau, on the North China Plain, and in China’s Far Northeast (see Figure 9.4D). While occasional freezes may reach as far as southern China, winters there are shorter and less severe. The cold air of the dry winter monsoon is partially deflected by the east-west mountain ranges of the Qin Ling, and the warm waters of the South China Sea moderate temperatures on land.

During the summer monsoon, as the continent warms, the air above it rises, pulling in wet, tropical air from the adjacent seas. The warm, wet air from the ocean deposits moisture on the land as seasonal rains. As the summer monsoon moves northwest, it must cross numerous mountain ranges and displace cooler air. Consequently, its effect is weakened toward the northwest. Thus, the Zhu Jiang basin in the far southeast is drenched with rain and has warm weather for most of the year (see Figure 9.4A), whereas the Chang Jiang basin, which lies in central China to the north of the Nan Ling range, receives about 5 months of summer monsoon weather. The North China Plain, north of the Qin Ling and Dabie Shan ranges, receives even less monsoon rain—about 3 months each year. Very little monsoon rain reaches the dry interior.

Korea and Japan have wet climates year-round, similar to those found along the Atlantic Coast of the United States, because of their proximity to the sea. They still have hot summers and cold winters because of their northerly location and exposure to the continental effects of the huge Eurasian landmass. Japan and Taiwan actually receive monsoon rains twice: once in spring, when the main monsoon moves toward the land, and again in autumn, as the winter monsoon forces warm air off the continent. This retreating warm air picks up moisture over the coastal seas, which is then deposited on the islands. Much of Japan’s autumn precipitation falls as snow, in particular in northern latitudes and at higher altitudes.

Natural Hazards

typhoon a tropical cyclone or hurricane in the western Pacific Ocean

THINGS TO REMEMBER

There are four main topographical zones, or “steps,” that form the East Asian continent.

There are four main topographical zones, or “steps,” that form the East Asian continent. Japan was created by volcanic activity along the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Japan was created by volcanic activity along the Pacific Ring of Fire. East Asia has two principal contrasting climates: the dry continental interior (west) and the monsoon east.

East Asia has two principal contrasting climates: the dry continental interior (west) and the monsoon east. East Asia faces a wide range of natural hazards, including earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and tropical storms (typhoons).

East Asia faces a wide range of natural hazards, including earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and tropical storms (typhoons).