Human Patterns over Time

East Asia is home to some of the most ancient civilizations on earth. Settled agricultural societies have flourished in China for more than 7000 years, which makes it the oldest continuous civilization in the world.

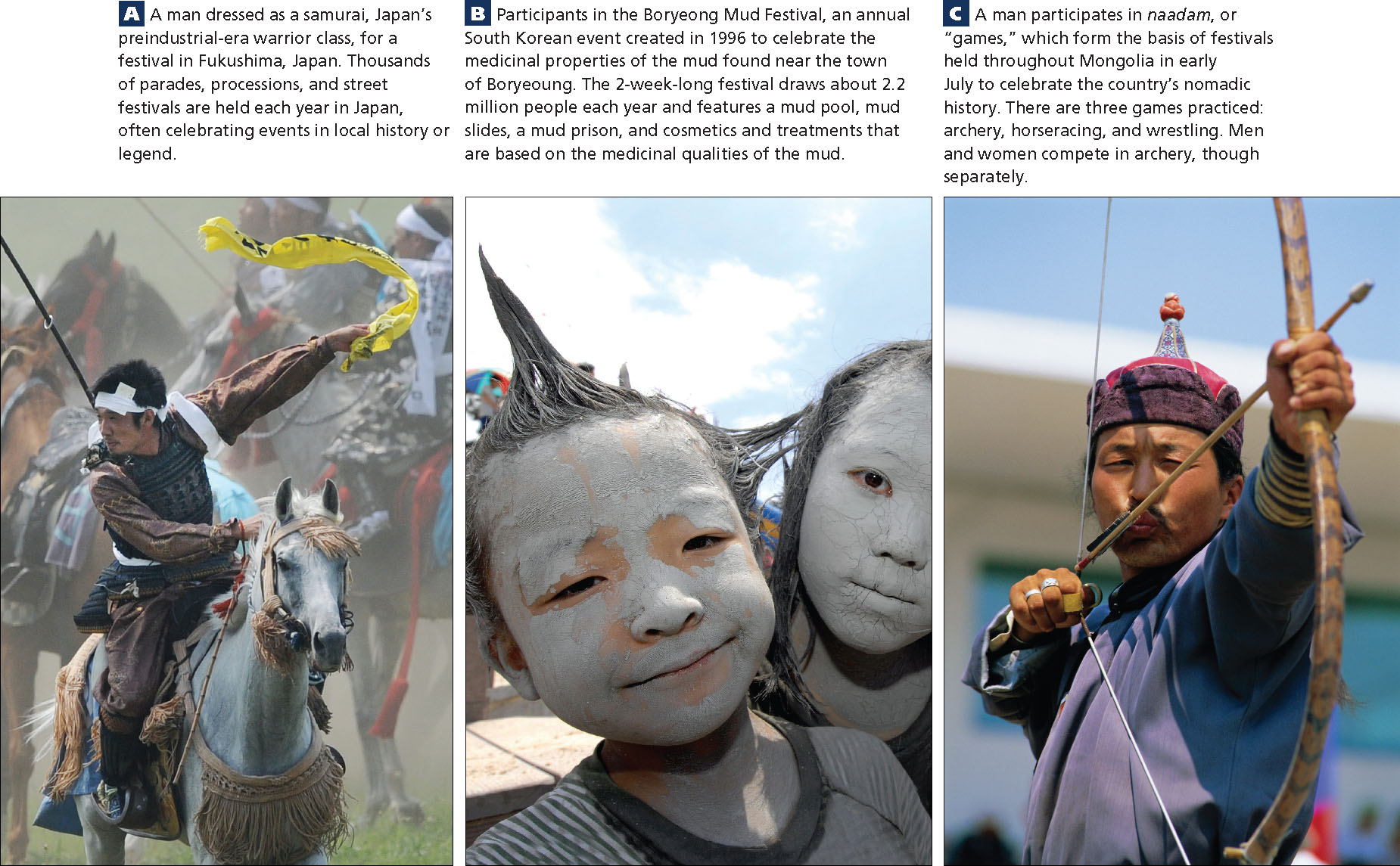

Chinese civilization evolved from several hearths, including the North China Plain, the Sichuan Basin, and the lands of interior Asia that were inhabited by nomadic pastoralists. On East Asia’s eastern fringe, the Korean Peninsula and the islands of Japan and Taiwan were profoundly influenced by the culture of China, but they were isolated enough that each developed a distinctive culture and maintained political independence most of the time. In the early twentieth century, Japan industrialized rapidly by integrating European influences that China disdained. As Figure 9.11 shows, both ancient and contemporary traditions are celebrated in East Asia today.

Bureaucracy and Imperial China

Although humans have lived in East Asia for hundreds of thousands of years, the region’s earliest complex civilizations appeared in various parts of what is now China about 4000 years ago. Written records exist only from the civilization that was located in north-central China. There, a small, militarized, feudal (see Chapter 4 for a discussion of feudalism) aristocracy controlled vast estates on which the majority of the population lived and worked as semi-enslaved farmers and laborers. The landowners usually owed allegiance to one of the petty kingdoms that dotted northern China. These kingdoms were relatively self-sufficient and well defended with private armies.

An important move away from feudalism came with the Qin empire (beginning in 221 b.c.e.), which instituted a trained and salaried bureaucracy in combination with a strong military to extend the monarch’s authority into the countryside. One part of the legacy of the Qin empire is shown in Figure 9.12B.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of East Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

The model for Confucian philosophy is what?

The model for Confucian philosophy is what?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Although the Qin empire was short-lived, what did subsequent empires do to survive?

Although the Qin empire was short-lived, what did subsequent empires do to survive?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

The Great Wall was built in response to what?

The Great Wall was built in response to what?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What major Chinese port was a British possession from the time of the Opium Wars until recently?

What major Chinese port was a British possession from the time of the Opium Wars until recently?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

After the Chinese Communist Revolution, how did the government control all aspects of economic social life?

After the Chinese Communist Revolution, how did the government control all aspects of economic social life?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How did Japan's political and economic development proceed after World War II?

How did Japan's political and economic development proceed after World War II?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The Qin system proved more efficient than the old feudal allegiance system it replaced. The estates of the aristocracy were divided into small units and sold to the previously semi-enslaved farmers. The empire’s agricultural output increased because the people worked harder to farm the land they now owned. In addition, the salaried bureaucrats were more responsible than the aristocrats they replaced, especially about building and maintaining levees, reservoirs, and other tax-supported public works that reduced the threat of flood, drought, and other natural disasters. Although the Qin empire was short-lived, subsequent empires maintained Qin bureaucratic ruling methods, which have proved essential in governing a united China.

Confucianism Molds East Asia’s Cultural Attitudes

Confucianism a Chinese philosophy that teaches that the best organizational model for the state and society is a hierarchy based on the patriarchal family

The Confucian Bias Toward Males

The model for Confucian philosophy was the patriarchal extended family. The oldest male held the seat of authority and was responsible for the well-being of everyone in the family. All other family members were aligned under the patriarch according to age and gender. Beyond the family, the Confucian patriarchal order held that the emperor was the grand patriarch of all China, charged with ensuring the welfare of society. Imperial bureaucrats were to do his bidding and commoners were to obey the bureaucrats.

Over the centuries, Confucian philosophy penetrated all aspects of East Asian society. Concerning the ideal woman, for example, a student of Confucius wrote: “A woman’s duties are to cook the five grains, heat the wine, look after her parents-in-law, make clothes, and that is all! When she is young, she must submit to her parents. After her marriage, she must submit to her husband. When she is widowed, she must submit to her son.” These concepts about limited roles for women affected society at large, where the idea developed that sons were the more valuable offspring, with public roles, while daughters were primarily servants within the home.

The Bias Against Merchants

For thousands of years, Confucian ideals were used to maintain the power and position of emperors and their bureaucratic administrators at the expense of merchants. In parable and folklore, merchants were characterized as a necessary evil, greedy and disruptive to the social order. At the same time, the services of merchants were sorely needed. Such conflicting ideas meant the status of merchants waxed and waned. At times, high taxes left merchants unable to invest in new industries or trade networks. At other times, however, the anti-merchant aspect of Confucianism was less influential, and trade and entrepreneurship flourished. Under communism, merchants again acquired a negative image; then when a market economy was encouraged, the social status of merchants once again rose.

Cycles of Expansion, Decline, and Recovery

Although the Confucian bureaucracy at times facilitated the expansion of imperial China (Figure 9.13), its resistance to change also led to periods of decline. Heavy taxes were periodically levied on farmers, bringing about farmer revolts that weakened imperial control. Threats from outside, particularly invasions by nomadic people from what are today Mongolia and western China, inspired the creation of massive defenses, such as the Great Wall (see Figure 9.12C), built along China’s northern border. Nevertheless, the Confucian bureaucracy always recovered from invasions. After a few generations, the nomads were indistinguishable from the Chinese. At the same time, Chinese culture and civilization absorbed a great mixture of different influences and has, as a result, itself changed.

One nomadic invasion did result in important links between China and the rest of the world. In the 1200s, the Mongolian military leader Genghis Khan and his descendants were able to conquer all of China. They then pushed west across Asia as far as Hungary and Poland (see Chapter 5). It was during the time of this Mongol empire (also known as the Yuan empire) that traders such as the Venetian Marco Polo made the first direct contacts between China and Europe. These connections proved much more significant for Europe, which was dazzled by China’s wealth and technologies, than for China, which saw Europe as backward and barbaric.

Indeed, from 1100 to 1600, China remained the world’s most developed region, despite enduring several cycles of imperial expansion, decline, and recovery. It had the largest economy, the highest living standards, and the most magnificent cities. Improved strains of rice allowed dense farming populations to expand throughout southern China and supported large urban industrial populations. Nor was innovation lacking: Chinese inventions included paper making, printing, paper currency, gunpowder, and improved shipbuilding techniques.

Why Did China Not Colonize an Overseas Empire?

During the well-organized Ming dynasty, 1368–1644, Zheng He, a Chinese Muslim admiral in the emperor’s navy, directed an expedition that could have led to China conquering a vast overseas empire. From 1405 to 1433, Zheng He sailed 250 ships—the biggest and most technologically advanced fleet that the world had ever seen. Zheng He took his fleet throughout Southeast Asia, across the Indian Ocean, and all the way to the east coast of Africa.

The lavish voyages of Zheng He were funded for almost 30 years, but they never resulted in an overseas empire like those established by European countries a century or two later. These newly explored regions simply lacked trade goods that China wanted. Moreover, back home the empire was continually threatened by the armies of nomads from Mongolia, so any surplus resources were needed for upgrading the Great Wall. Eventually the emperor decided that Zheng He’s explorations were not worth the effort. In the years following Zheng He’s voyages, China reduced its contacts with the rest of the world as the emperor focused on repelling invaders from Mongolia. As a result, the pace of technological change slowed, leaving China ill prepared to respond to growing challenges from Europe after 1600. China did, however, become a regional colonizing power by extending control to include territories in Central Asia and Southeast Asia (see Figure 9.13).

European and Japanese Imperialism

By the mid-1500s, during Europe’s Age of Exploration, Spanish and Portuguese traders interested in acquiring China’s silks, spices, and ceramics found their way to East Asian ports. To exchange, they brought a number of new food crops from the Americas, such as corn, peppers, peanuts, and potatoes. These new sources of nourishment contributed to a spurt of economic expansion and population growth during the Qing, or Manchurian, dynasty (1644–1912), and by the mid-1800s, China’s population was more than 400 million, which can be compared to about 270 million in Europe at the same time.

By the nineteenth century, European merchants gained access to Chinese markets and European influence increased markedly. In exchange for Chinese silks and ceramics, British merchants supplied opium from India, which was one of the few things that Chinese merchants would trade for. The emperor attempted to crack down on this drug trade because of its debilitating effects on Chinese society. The result was the Opium Wars (1839–1860), in which Britain badly defeated China. Hong Kong became a British possession, and British trade, including opium, expanded throughout China, well into the twentieth century (see Figure 9.12D).

The final blow to China’s long preeminence in East Asia came in 1895, when a rapidly modernizing Japan won a spectacular naval victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War (and to solidify its emerging regional dominance, Japan also defeated Russia). After this first defeat by the Japanese, the Qing dynasty made only halfhearted attempts at modernization, and in 1912, it was overthrown by an internal revolt and collapsed. Beginning with the decline of the Qing Empire (1895) until China’s Communist Party took control in 1949, much of the country was governed by provincial rulers in rural areas and by a mixture of Chinese, Japanese, and European administrative agencies in the major cities.

China’s Turbulent Twentieth Century

In response to the absence of central state authority, two rival reformist groups arose in China in the early twentieth century. The Nationalist Party, known as the Kuomintang (KMT), was an urban-based movement that appealed to workers as well as the middle and upper classes. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), on the other hand, found its base in rural areas among peasants. At first the KMT gained the upper hand, uniting the country in 1924. However, Japan’s invasion of China in 1931 changed the dynamic.

By 1937, Japan had control of most major Chinese cities. The KMT did not resist the Japanese effectively and were confined to the few deep interior cities not in Japanese control. The CCP, however, waged a constant guerilla war against the Japanese throughout rural China. This resistance gained the CCP heroic status. Japan’s brutal occupation caused 10 million Chinese deaths, including widespread killing of civilians in the city of Nanjing—the so-called “Rape of Nanjing.” Such events, as well as the keeping of local “comfort women” (forced prostitution) by the Japanese army in the occupied territories, still complicate the relationship between Japan and its East Asian neighbors. When Japan finally withdrew in 1945, defeated at the end of World War II by the United States, Russia, and other Allied forces, the vastly more popular CCP pushed the KMT out of the country and into exile in Taiwan. In 1949, the CCP, led by Mao Zedong, proclaimed the country the “People’s Republic of China,” with Mao as president.

Mao’s Communist Revolution

Mao Zedong’s revolutionary government became the most powerful China ever had. It dominated all the outlying areas of China—the Far Northeast, Inner Mongolia, and western China (Xinjiang)—and launched a brutal occupation of Tibet (Xizang). The People’s Republic of China was in many ways similar to past Chinese empires. The Chinese Communist Party replaced the Confucian bureaucracy and Mao Zedong became a sort of emperor with unquestioned authority. China received support from the Soviet Union, but the two communist states remained wary of each other for decades.

Among the early beneficiaries of the revolution were the masses of Chinese farmers and landless laborers. On the eve of the revolution, huge numbers lived in abject poverty. Famines were frequent, infant mortality was high, and life expectancy was low. The vast majority of women and girls held low social status and spent their lives in unrelenting servitude.

The revolution drastically changed this picture. All aspects of economic and social life became subject to central planning by the Communist Party. Land and wealth were reallocated, often resulting in an improved standard of living for those who needed it most. Heroic efforts were made to improve agricultural production and to reduce the severity of floods and droughts. The masses, regardless of age, class, or gender, were mobilized to construct almost entirely by hand huge public works projects—roads, dams, canals, whole mountains terraced into fields for rice and other crops. “Barefoot doctors” with rudimentary medical training dispensed basic medical care, midwife services, and nutritional advice to people in the remotest locations. Schools were built in the smallest of villages. Opportunities for women became available, and some of the worst abuses against them were stopped—such as the crippling binding of women’s feet to make them small and childlike. Most Chinese people who are old enough to have witnessed these changes say that the revolution did a great deal to improve overall living standards for the majority.

Mao’s Missteps

Great Leap Forward an economic reform program under Mao Zedong intended to quickly raise China to the industrial level of Britain and the United States

Cultural Revolution a political movement launched in 1966 to force the entire population of China to support the continuing revolution

Changes After Mao

Two years after Mao’s death, a new leadership formed around Deng Xiaoping. Limited market reforms were instituted, but the Communist Party retained tight political control. In 2009, after more than 30 years of reform and remarkable levels of economic growth, China’s economy became the third largest in the world, behind that of the European Union and the United States. It passed Japan (although Japan’s per capital wealth is still five times that of China’s) when China managed to weather the world recession beginning in 2008 better than expected. However, the disparity of wealth in China has been increasing for some years, human rights are still often abused, and political activity remains tightly controlled even as discontent boils over into open protests against government foibles.

Japan Becomes a World Leader

Although China’s influence was dominant in East Asia for thousands of years, for much of the twentieth century, Japan, with only one-tenth the population and 5 percent of the land area of China, controlled East Asia economically and politically. Japan’s rise as a modern global power resulted largely from its response to challenges from Europe and North America.

Beginning in the mid-sixteenth century, active trade with Portuguese colonists brought new ideas and technology that strengthened Japan’s wealthier feudal lords (shoguns), allowing them to unify the country under a military bureaucracy. However, the shoguns monopolized contact with the European outsiders, allowing no Japanese people to leave the islands, on penalty of death.

A second period of radical change came with the arrival in Tokyo Bay in 1853 of a small fleet of U.S. naval vessels. The foreigners, carrying military technology far more advanced than Japan’s, forced the Japanese government to open the economy to international trade and political relations. In response, a group of reformers (the Meiji) seized control of the Japanese government, setting the country on a crash course of modernization and industrial development that became known as the Meiji restoration. During this period, Japanese students were sent abroad and experts were recruited from around the world, especially from Western nations, to teach everything from foreign languages to modern military technology. Investments emphasized infrastructure development, especially in transportation and communication. The improvements that resulted enabled Japan’s economy to grow rapidly, surpassing China’s in size in the early twentieth century.

Between 1895 and 1945, Japan fueled its economy with resources from a vast colonial empire. Equipped with imported European and North American military technology, its armies occupied first Korea, then Taiwan, then coastal and eastern China, and eventually Indonesia and much of Southeast Asia, as shown in Figure 9.14. Many of the people of these areas still harbor resentment about the brutality they suffered at Japanese hands. Japan’s imperial ambitions ended with its defeat in World War II and its subsequent occupation by U.S. military forces until 1952.  204. JAPANESE STILL RESOLVING FEELINGS ABOUT THE WAR

204. JAPANESE STILL RESOLVING FEELINGS ABOUT THE WAR

In the immediate post-war era, the U.S. government imposed many social and economic reforms. Japan was required to create a democratic constitution and reduce the emperor to symbolic status. Its military was reduced dramatically, forcing it to rely on U.S. forces to protect it from attack. With U.S. support, Japan rebuilt rapidly after World War II, and it eventually became a giant in industry and global business, exporting automobiles, electronic goods, and many other products. Japan’s economy is still among the world’s largest, wealthiest, and most technologically advanced (see Figure 9.12F and Figure 9.17D).

Chinese and Japanese Influences on Korea, Taiwan, and Mongolia

The history of the remaining East Asia region is largely grounded in what transpired in China and Japan.

The Korean War and Its Aftermath

Korea was a unified but poverty-stricken country until 1945. At the end of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union, as victorious allies, agreed to divide the former Japanese colony. The Soviet Union occupied and established a communist regime to the north, while the United States took control of the southern half of the Korean peninsula, where it instituted reforms similar to those in Japan. After the United States withdrew its troops in the late 1940s, North Korea attacked South Korea. The United States returned to defend the south, leading a 3-year war against North Korea and its allies, the Soviet Union and Communist China.

After great loss of life on both sides and devastation of the peninsula’s infrastructure, the Korean War ended in 1953 in a truce and the establishment of a demilitarized zone (DMZ) near the 38th parallel, which acts as the de facto border between the North and the South. This 2.5 mile (4 kilometers) wide border is called “demilitarized” because it is a buffer zone not claimed by either side, although the surrounding area is heavily armed. North Korea closed itself off from the rest of the world, and to this day it remains isolated, impoverished, and defensive, occasionally gaining international attention by hinting at its nuclear potential (see Figure 9.21D). Meanwhile, South Korea has developed into a prosperous and technologically advanced market economy. Relations between the two countries remain tense, with occasional skirmishes breaking out along the border.

Taiwan’s Uncertain Status

For thousands of years, Taiwan was a poor, agricultural island on the periphery of China; then between 1895 and 1945 it became part of Japan’s regional empire. In 1949, when the Chinese nationalists (the Kuomintang) were pushed out of mainland China by the Chinese Communist Party, they set up an anti-communist government in Taiwan, naming it the Republic of China (ROC). For the next 50 years, with U.S. aid and encouragement, the ROC became a modern industrialized economy, which quickly dwarfed that of China and remained dominant until the 1990s, serving as a prosperous icon of capitalism right next door to massive Communist China.

Today, Taiwan remains an economic powerhouse. Taiwanese investors have been especially active in Shanghai and the cities of China’s southeast coast. Yet mainland China has never relinquished claim to Taiwan. As China’s economic and military power have increased, the United Nations, the World Bank, and the United States, along with most other countries, agencies, and institutions, have judiciously tiptoed around the issue of whether Taiwan should continue as an independent country or be downgraded to simply a province of China. Taiwan itself remains divided over just how strongly it should hold on to its sovereignty (see Figure 9.21C).

Mongolia Seeks Its Own Way

For millennia, Mongolia’s nomadic horsemen periodically posed a threat to China, so much so that the Great Wall was built and repeatedly reinforced and extended to combat them (see Figure 9.12C). China has long been obsessed with both deflecting and controlling its northern neighbor; and China did control Mongolia from 1691 until the 1920s. Revolutionary communism spread to Mongolia soon thereafter, and Mongolia continued as an independent communist country under Soviet, not Chinese, guidance until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1989. Communism brought education and basic services. Literacy for both men and women rose above 95 percent. Deeply suspicious of both Russia and China, Mongolia has since 1989 been on a difficult road to a market economy. In need of cash to participate in the modern world, families have elected to abandon nomadic herding and permanently locate their portable ger homes near Ulan Bator and search for paid employment. While the economy has developed, the rapid and drastic change in lifestyle has also resulted in broken homes, increasing personal debt, and poverty, in a society that formerly took pride in an egalitarian if not prosperous standard of living.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The histories of East Asian countries are deeply intertwined, and Confucian thought still permeates the entire region.

The histories of East Asian countries are deeply intertwined, and Confucian thought still permeates the entire region. For six centuries, from 1100 to 1600, China was the world’s most developed region, despite cycles of imperial expansion, decline, and recovery.

For six centuries, from 1100 to 1600, China was the world’s most developed region, despite cycles of imperial expansion, decline, and recovery. In recent times, the countries of East Asia have followed very different political paths toward development.

In recent times, the countries of East Asia have followed very different political paths toward development. Japan has long-term cultural ties to the mainland of East Asia and has also exercised influence over the region, primarily through conquest. For most of the twentieth century, it has been the dominant economy in the region, only recently losing that status to China in 2010.

Japan has long-term cultural ties to the mainland of East Asia and has also exercised influence over the region, primarily through conquest. For most of the twentieth century, it has been the dominant economy in the region, only recently losing that status to China in 2010. Taiwan and South Korea emerged after World War II as rapidly industrializing countries, while Mongolia until recently retained communist connections to the Soviet Union. North Korea remains a communist country and is extremely defensive and cut off from the wider world.

Taiwan and South Korea emerged after World War II as rapidly industrializing countries, while Mongolia until recently retained communist connections to the Soviet Union. North Korea remains a communist country and is extremely defensive and cut off from the wider world.