Economic and Political Issues

state-aided market economy an economic system based on market principles such as private enterprise, profit incentives, and supply and demand, but with strong government guidance; in contrast to the free market (limited government) economic system of the United States and, to a lesser degree, Europe

export-led growth an economic development strategy that relies heavily on the production of manufactured goods destined for sale abroad

More recently, the differences among East Asian countries have diminished as China and Mongolia have set aside strict central planning and adopted reforms that rely more on market forces. China also relies heavily on exports of its manufactured goods to North America and Europe. Politically, however, contrasts remain stark. While Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Mongolia have become democracies, the North Korean dictatorship maintains total control over politics and the media. In China, there is some experimentation with democracy at the local level, but the central government generally acts as a force against widespread democratic participation.

The Japanese Miracle

Throughout the nineteenth century, the economies of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan were minuscule compared with China’s. During the twentieth century, though, all three grew tremendously, in part because of ideas that originated in Japan.

Japan Rises from Ashes

Japan’s recovery after its crippling defeat at the end of World War II is one of the most remarkable tales in modern history. Except for Kyoto, which was spared because of its historical and architectural significance, all of Japan’s major cities were destroyed by the United States. Most notably, the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons and leveled Tokyo with incendiary bombs.  205. SURVIVORS RECALL THE NUCLEAR BOMBING OF HIROSHIMA

205. SURVIVORS RECALL THE NUCLEAR BOMBING OF HIROSHIMA

Key to Japan’s rapid recovery was its state-aided market economy, in which government guided private investors in creating new manufacturing industries. The overall strategy was one of export-led economic growth, with the Japanese government negotiating trade agreements with the United States and Europe. These and other deals ensured that large and wealthy foreign markets would be willing to import Japanese manufactured goods. Japan’s economic recovery based on a state-aided and export-oriented market economy was imitated in South Korea, Taiwan, countries in Southeast Asia, and eventually in China and many other parts of the developing world. Also central to Japan’s recovery, but less imitated abroad, were arrangements between the government, major corporations, and labor unions that guaranteed lifetime employment by a single company for most workers in return for relatively modest pay.

The government-engineered trade and labor arrangements produced explosive economic growth of 10 percent or more annually between 1950 and the 1970s. The leading sectors were export-oriented automobile and electronics manufacturing. Japanese brand names such as Sony, Panasonic, Nikon, and Toyota became household words in North America and Europe. Products made by these companies sold at much higher volumes than would have been possible in the then relatively small Japanese and nearby Asian economies. Although growth slowed considerably both during the 1990s and again beginning in 2007, Japan’s postwar “economic miracle” continues to have an immense worldwide impact as a model, and Japan remains a significant actor in the world economy. Japan purchases resources from all parts of the world for its industries and domestic use. These purchases and investments in various local economies continue to create jobs for millions of people around the globe.

Productivity Innovations in Japan

just-in-time system the system pioneered in Japanese manufacturing that clusters companies that are part of the same production system close together so that they can deliver parts to each other precisely when they are needed

kaizen system a system of continuous manufacturing improvement, pioneered in Japan, in which production lines are constantly adjusted, improved, and surveyed for errors to save time and money and ensure that fewer defective parts are produced

Mainland Economies: Communists in Command

After World War II, economic development on East Asia’s mainland proceeded on a dramatically different course than it did in Japan. Communist economic systems transformed poverty-ridden China, Mongolia, and North Korea. Private property was abolished, and the state took full control of the economy, loosely following the example of the Soviet command, or centrally planned, economy (see Chapter 5). These sweeping changes transformed life for the poor majority, but ultimately proved less resilient and successful than was hoped.

By design, most people in the communist economies could not consume more than the bare necessities. On the other hand, the policy—called the “iron rice bowl” in China—of guaranteeing nearly everyone a job for life, sufficient food, basic health care, and housing was better than what they had before. One drawback was that overall productivity remained low.

The Commune System

When the Communist Party first came to power in China in 1949, its top priority was to make monumental improvements in both agricultural and industrial production. The communist governments in North Korea and Mongolia held similar goals, though these countries had much smaller populations and resource bases to work with.

In the years following World War II, an aggressive agricultural reform program joined small landholders together into cooperatives so that they could pool their labor and resources to increase production. In time, the cooperatives became full-scale communes, with an average of 1600 households each. The communes, at least in theory, took care of all aspects of life. They provided health care and education and built rural industries to supply such items as simple clothing, fertilizers, small machinery, and eventually even tractors. The rural communes also had to fulfill the ambitious expectations that the leaders in Beijing had of better flood control, expanded irrigation systems, and especially, of increased food production.

The Chinese commune system met with several difficulties. Rural food shortages developed because farmers had too little time to farm. They were required to spend much of their time building roads, levees, terraces, and drainage ditches, or working in the new rural industries. Local Communist Party administrators often compounded the problem by overstating harvests in their communes to impress their superiors in Beijing. The leaders in Beijing responded by requiring larger food shipments to the cities, which caused even greater food shortages in the countryside.

Although the Chinese agricultural communes were inefficient and created devastating food scarcities during the Great Leap Forward, they did eventually result in a stable food supply that kept Chinese people well fed.

In North Korea, the Communists have pushed military strength at the expense of broader economic development. Meanwhile, agriculture has been so neglected that production is precarious, with food aid from its immediate neighbors or the United States a yearly necessity, and famine a constant threat. In recent years, North Korea has used rocket launchings, nuclear tests, and even threat of war to intimidate its neighbors, and is selling its military technology abroad to pay for food imports. The U.S. government intermittently suspends food aid to encourage more peaceful policies from the North Korean leadership, but with limited results.

In Mongolia, communist policy followed the Soviet model of collectivization but was tailored to Mongolia’s economy, which at the time was largely one of herding and agriculture. There were minimal changes to the nomadic pastoralist way of life, but the roles of mining and industry were emphasized, and the contribution to GDP by herding and forestry declined to less than 20 percent.

Focus on Heavy Industry

The Communist leadership in China, North Korea, and Mongolia believed that investment in heavy industry would dramatically raise living standards. Massive investments were made in the mining of coal and other minerals and in the production of iron and steel. Especially in China, heavy machinery was produced to build roads, railways, dams, and other infrastructure improvements that leaders hoped would increase overall economic productivity. However, much as in India (see Chapter 8), the vast majority of the population remained impoverished agricultural laborers who received little benefit from industries that created jobs mainly in urban areas. Not enough attention was paid to producing consumer goods (such as cheap pots, pans, hand tools, and other household items) that would have driven modest internal economic growth and improved living standards for the rural poor. Even in the urban areas, growth remained sluggish because, as also was the case in the Soviet command economy, small miscalculations by bureaucrats resulted in massive shortages and production bottlenecks that constrained economic growth.

Struggles with Regional Disparity

regional self-sufficiency an economic policy in Communist China that encouraged each region to develop independently in the hope of evening out the wide disparities in the national distribution of resources production and income

Market Reforms in China

responsibility system in the 1980s, a decentralization of economic decision making in China that returned agricultural decision making to the farm household level, subject to the approval of the commune

regional specialization the encouragement of specialization rather than self-sufficiency in order to take advantage of regional variations in climate, natural resources, and location

China’s market reforms have transformed not only China’s economy but also the economies of wider East Asia and indeed the whole world. Today China is the world’s largest producer of manufactured goods, supplying consumers across the globe. Of the other Communist-led countries, Mongolia has participated in this revolution only moderately, mainly as a raw material exporter, and North Korea has not participated at all.

Urbanization, Development, and Globalization in East Asia

Geographic Insight 3

Urbanization and Development: China’s move to join the global economy more than three decades ago has led to spectacular urban growth, a stronger emphasis on consumerism, and a massive rise in industrial and agricultural pollution of the air, water, and soil.

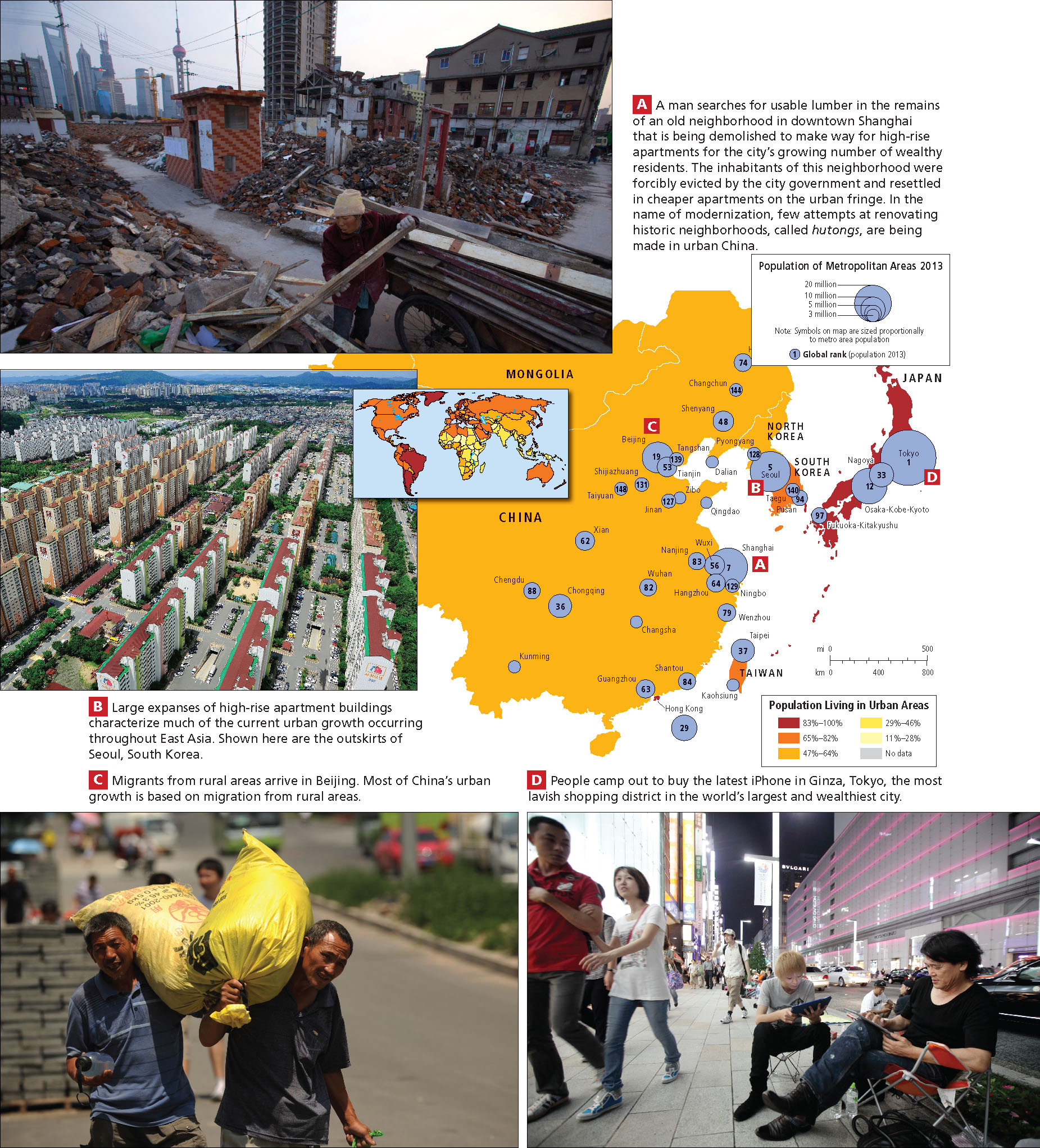

Across East Asia, cities have grown rapidly over the last several decades as urban industrial development has accelerated, focused on production for the global market (see the Figure 9.17 map). China has undergone the most massive urbanization in the world’s history. Since 1980, when market reforms were initiated, the urban population has more than tripled, and is now nearly 700 million. This explosive economic development has been fueled largely by the highly globalized economies of China’s big coastal cities, whose urban factories now supply consumers throughout the world. The urban economic growth has been so spectacular that in 2012, nineteen of the 20 fastest-growing cities in the world, as measured by increase in GDP per capita, were in China. Despite the rapid growth, urbanites still represent only 51 percent of China’s total population, so more growth is likely, whereas in every other country in the region—even North Korea—the majority of the population has been urban for at least two decades. Most East Asian cities are extremely crowded, so future growth is a challenge for planners and residents (see Figure 9.17A, B).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in East Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What happened to many of the former residents of Pudong, the new financial center of Shanghai?

What happened to many of the former residents of Pudong, the new financial center of Shanghai?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Migrants to urban areas who ignore the hukou system are considered part of what population?

Migrants to urban areas who ignore the hukou system are considered part of what population?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

The urbanized region that stretches from cities of Tokyo and Yokohama on Honshu south through the coastal zones of the inland sea to the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu is home to what percent of Japan's population?

The urbanized region that stretches from cities of Tokyo and Yokohama on Honshu south through the coastal zones of the inland sea to the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu is home to what percent of Japan's population?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Spatial Disparities

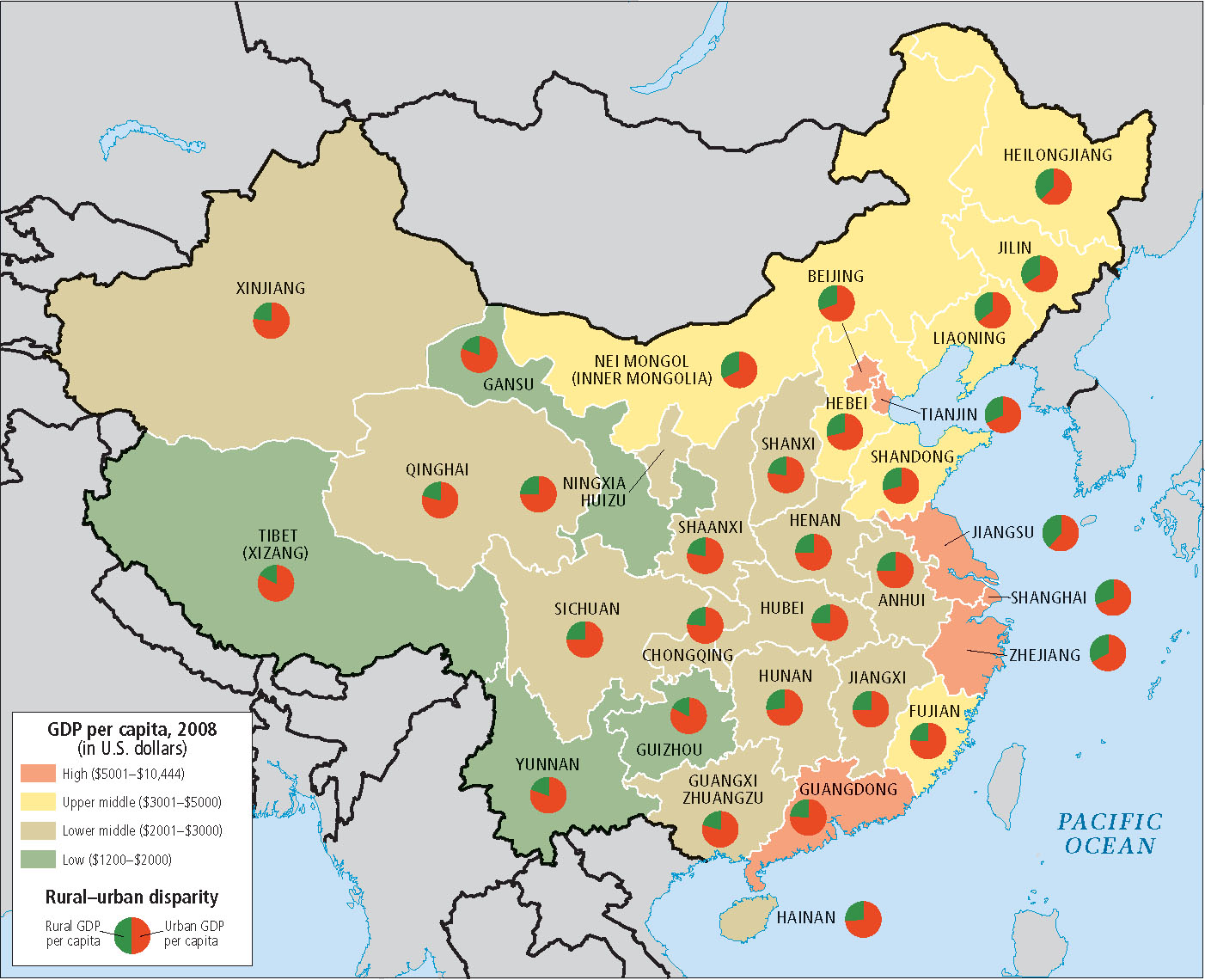

The patterns of public and private investment that accompany urbanization have led to rural areas lagging behind urban areas in access to jobs and income, education, and medical care. The map in Figure 9.16 depicts the problem. GDP per capita is significantly lower in China’s interior provinces than it is in coastal provinces, and within each province there is a disparity between rural and urban places, shown in pie diagrams of rural versus urban incomes. Notice that rural–urban GDP disparities, while still significant, are less extreme in northeastern and coastal provinces than in interior and western provinces. Similar rural-to-urban disparity patterns are found in all other countries in East Asia, including North Korea.

206. OLD BEIJING MAKING WAY FOR MODERN DEVELOPMENT

206. OLD BEIJING MAKING WAY FOR MODERN DEVELOPMENT

219. SOME CHINESE FEAR PRIVATE PROPERTY LAW WILL COST THEM THEIR HOMES

219. SOME CHINESE FEAR PRIVATE PROPERTY LAW WILL COST THEM THEIR HOMES

International Trade and Special Economic Zones

special economic zones (SEZs) free trade zones within China, which are commonly called export processing zones (EPZs) elsewhere

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Transportation Improvements

Recently, ETDZs in the interior have had higher rates of growth than those on the coast. One reason is that China spends 9 percent of its GDP on transportation improvements (recently, the United States spent 2.4 percent), which has made central and western China more accessible. New highways and railroads may eventually enable the interior to catch up with the economic development of the coast. The world’s longest high-speed rail now takes a traveler from Beijing to southern China in 10 rather than 22 hours, and it is routed through central China, not along the coast.

growth poles zones of development whose success draws more investment and migration to a region

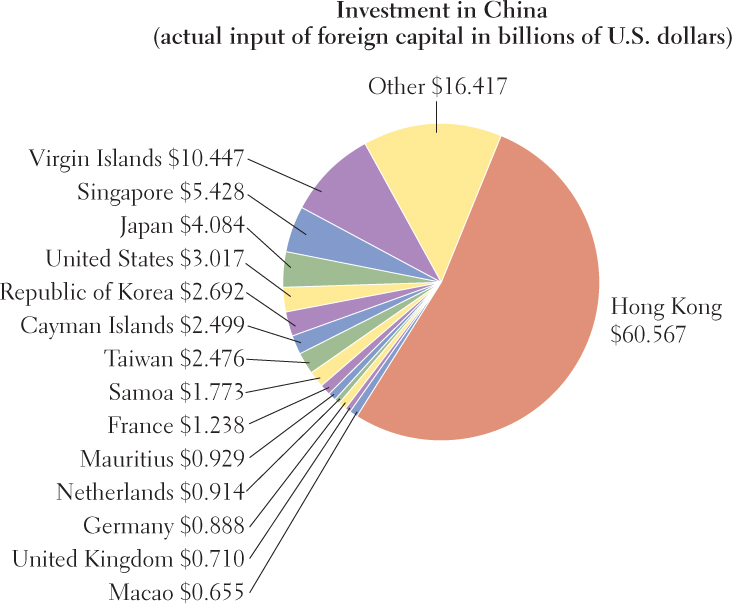

While Hong Kong’s democracy has been curtailed, political freedom is more evident there than elsewhere in China, and its role as China’s link to the global economy has continued. Before 1997, some 60 percent of foreign investment in China was funneled through Hong Kong, and since then Hong Kong has remained the financial hub for China’s booming southeastern coast (Figure 9.19). Several of China’s SEZs and ETDZs are located in close proximity to Hong Kong. Because so much of this investment comes from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, Hong Kong is an important regional financial hub as well.  220. AS HONG KONG ENTERS SECOND DECADE UNDER CHINA, CITY PONDERS PLACE IN ECONOMIC GIANT

220. AS HONG KONG ENTERS SECOND DECADE UNDER CHINA, CITY PONDERS PLACE IN ECONOMIC GIANT

Shanghai’s Latest Transformation

Shanghai has a long history as a trendsetter. Its opening to Western trade in the early nineteenth century spawned a period of phenomenal economic growth and cultural development that led it to be called the “Paris of the East.” As a result of China’s recent reentry into the global economy, Shanghai is undergoing another boom, which has enriched some people and dislocated others (see Figure 9.17A). On average, residents of Shanghai are now as affluent as people in Central European countries like Poland and Hungary, and if current growth trends continue, their wealth will soon surpass that of many other countries as well. Shanghai today has the world’s busiest cargo port, and the region around Shanghai is now responsible for as much as a quarter of China’s GDP.

In less than a decade, the city’s urban landscape has been remade by the construction of more than a thousand business and residential skyscrapers; subway lines and stations; highway overpasses; bridges; and tunnels. Shanghai’s shopping district on Nanjing Road is as imposing as any such district around the world. For hundreds of miles into the countryside, suburban development linked to Shanghai’s economic boom is gobbling up farmland, and displaced farmers have rioted.

Pudong (see Figure 9.35), the new financial center for the city, sits across the Huangpu River from the Bund—Shanghai’s famous, elegant row of big brownstone buildings that served as the financial capital of China until half a century ago. Previously, Pudong was a maze of dirt paths and sprawling neighborhoods of low, tile-roofed houses, but its former residents were pushed out to make way for soaring high-rises. New construction is restricted in the historic section of the Bund, which is another reason why the centrality of Pudong has been attractive as a new business center. The Oriental Pearl Tower has become a visual symbol for the economic vitality of Pudong, the city of Shanghai, and all of China.

Shanghai’s long-standing role as a window to the outside world has meant that it often is host to quirky behavior that is less common elsewhere in the country. For example, for years the people of Shanghai have relaxed in public in their pajamas—light, loose cotton tops and bottoms stamped with images of puppies or butterflies. The city government has tried to squelch the custom, but the citizens have proved recalcitrant. The police seem to understand that images of them arresting old and young alike for wearing pajamas would be ludicrous, so for now the issue is unresolved.

Urban Labor Surpluses and Shortages

Spectacular urban growth in East Asia was based on hundreds of millions of new urban migrants who were willing to put up with adverse conditions to earn a little cash. However, so many factories, businesses, and shopping malls were built or were under construction that by 2005, experienced and skilled workers of all types were increasingly in short supply. Those with management skills were especially scarce.

To attract employees, some factory owners in China offered higher pay, better working conditions, and shorter workdays or increased time off. The extra costs these changes imposed meant that China was no longer the cheapest place to manufacture products. Some factories moved to Vietnam, Bangladesh, and countries in Africa with even cheaper labor. The more technologically sophisticated items, such as cell phones and computers, which contain relatively expensive components and are therefore less dependent on the lowest possible wages at the assembly site, could absorb the higher wages for workers, at least for a while. Then the global recession, which was felt in Asia by 2008, changed the dynamic yet again. Demand for China’s products dropped, and factories quickly laid off workers or shut down entirely. Throngs of urban workers returned to their farms and villages, dejected about not being able to help their families and confused about what the future would hold for them. The Chinese economy has remained robust after the recession, in no small part because domestic purchasing power and consumption have increased and thus diminished the dependency on shaky Western economies, which means that the outlook for most Chinese workers is still positive. These ups and downs in China’s labor market added a new twist to the story of Li Xia, whom we met in the vignette that opens this chapter.

VIGNETTE

Li Xia and her sister returned home to rural Sichuan a second time. With the money she had saved from her second job in Dongguan, Xia tried to open a bar in the front room of her parents’ house. She hoped to introduce the popular custom of karaoke singing she had enjoyed in the city, but people in her village could not stand the noise, and family tensions rose. Xia’s sister, delighted to be home with her husband and baby, quickly found a job in a small new fruit-processing factory—a rural enterprise. Her husband began farming again to fill the new demand for organic vegetables among the middle class in the Sichuan city of Chongqing.

In early 2007, amid all this success in her family and the failure of her own bar, news that training was now available in Dongguan for skilled electronics assemblers convinced Xia to try again. Past experience with the bureaucracy and her knowledge of Dongguan helped Xia to sign up for the electronics training. The cost of tuition was to come out of her wages, which were only U.S.$350 a month rather than the U.S.$400 she had thought she would be paid. Also, the waiting list for an apartment was long. She would need several years to repay her tuition, so she went back to shared quarters with her friends.

In November of 2008, Xia heard rumors that a global recession was causing orders for electronics to be cut and that she might soon be laid off. But her factory limped along with a reduced staff. Then, miraculously, in June of 2009, orders picked up. Consumers in America had continued to buy electronics even as they downsized their homes and cars. Electronic inventories in America were down, so orders for products from Xia’s factory went up significantly. And with so many laid-off workers returning home, the apartment wait list had shortened drastically. Now the apartment developers were only too happy to give her a firm move-in date. Meanwhile, the landscape of Dongguan has filled with shuttered export industries and empty shopping malls in the wake of the global downturn, so Xia’s migration back and forth between the city and the countryside is likely to persist. [Sources: USA Today, National Public Radio, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, China Daily, Plastics News. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

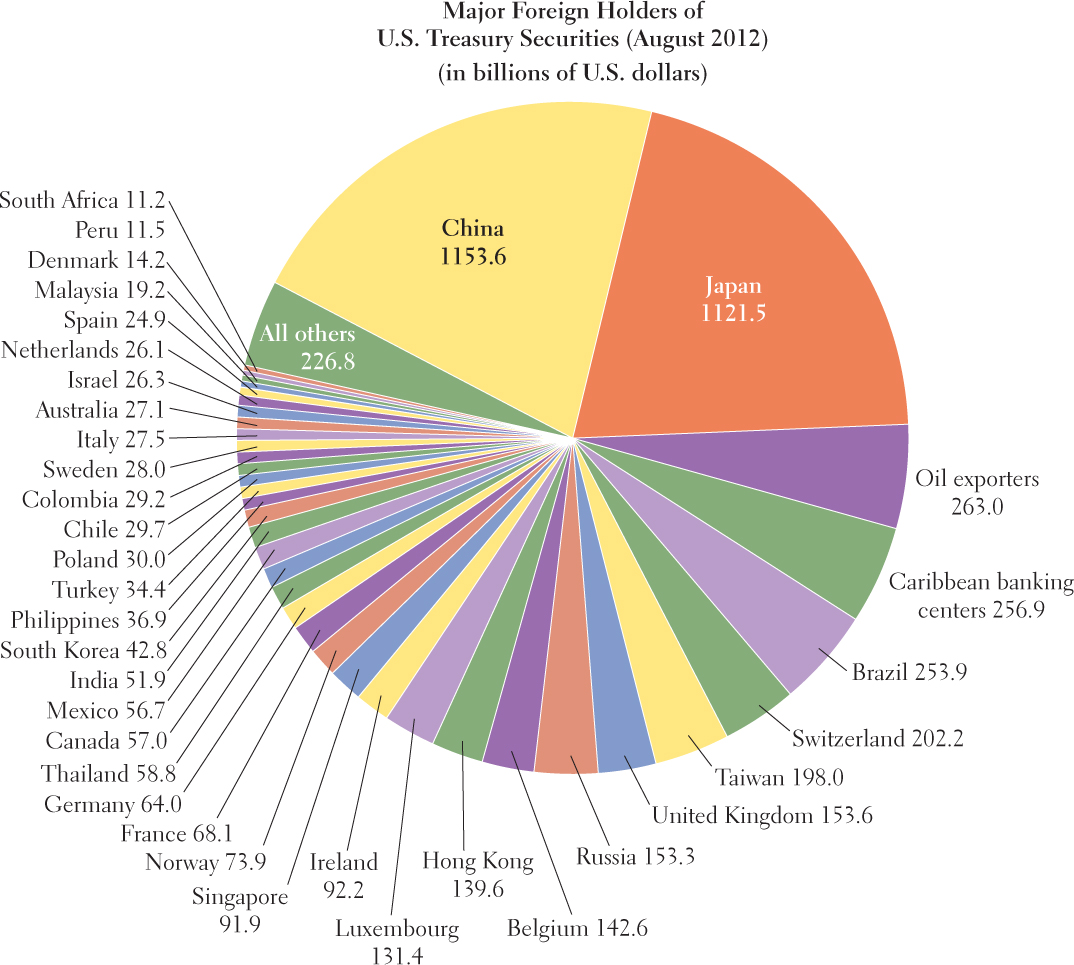

East Asia’s Role as Mega-Financier

As rampant consumers during the first decade of the twenty-first century, Americans borrowed both from themselves and others. By 2012, foreign banks owned 35 percent of U.S. public debt—and of that 35 percent, Chinese and Japanese banks owned 42 percent, or about U.S.$2.3 trillion (Figure 9.20). China and Japan both had a great deal of cash because of their successful export economies, and they lent the money partly to ensure that consumers in the United States would continue to buy their goods. On the one hand, many in the United States are afraid that China, especially, can wield a lot of economic power because it holds so much of the U.S. debt. On the other hand, both sides are equally dependent on each other for continued economic success, so Asian financing of U.S. government debt is likely to continue.

Elsewhere in the world, East Asians are able to use their reserves to finance development and thereby secure privileged trade deals. In recent years, China’s lending to developing countries has outpaced even that of the World Bank. Often these loans are made in return for guarantees that the recipient country will supply China with needed industrial materials, especially fossil fuels.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Key to Japan’s rapid economic recovery after World War II was close cooperation between the government and private investors to create new, export-based industries, primarily those in the automotive and electronics sectors.

Key to Japan’s rapid economic recovery after World War II was close cooperation between the government and private investors to create new, export-based industries, primarily those in the automotive and electronics sectors. Japanese management innovations known as the just-in-time and kaizen systems also were important to economic recovery; they were so successful that they diffused and created clusters of economic activity in different places around the world.

Japanese management innovations known as the just-in-time and kaizen systems also were important to economic recovery; they were so successful that they diffused and created clusters of economic activity in different places around the world. In the 1980s, China’s leaders enacted market reforms that changed the country’s economy in significant ways, and subsequently those market reforms transformed the region and indeed the whole world.

In the 1980s, China’s leaders enacted market reforms that changed the country’s economy in significant ways, and subsequently those market reforms transformed the region and indeed the whole world. Geographic Insight 3Urbanization and Development China’s cities are growing quickly, with explosive economic development fueled by foreign direct investment and access to overseas markets.

Geographic Insight 3Urbanization and Development China’s cities are growing quickly, with explosive economic development fueled by foreign direct investment and access to overseas markets.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in East Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What happened in Tiananmen Square in 1989?

What happened in Tiananmen Square in 1989?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

When was democracy in Taiwan established?

When was democracy in Taiwan established?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is North Korea purchasing with money earned from sales of its military technology abroad?

What is North Korea purchasing with money earned from sales of its military technology abroad?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Power and Politics in East Asia

Geographic Insight 4

Power and Politics: As economic development has grown across East Asia, pressures for more political freedoms have also risen. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are now among the more politically free places in the world, and pressure for similar levels of freedom is intensifying in China and North Korea.

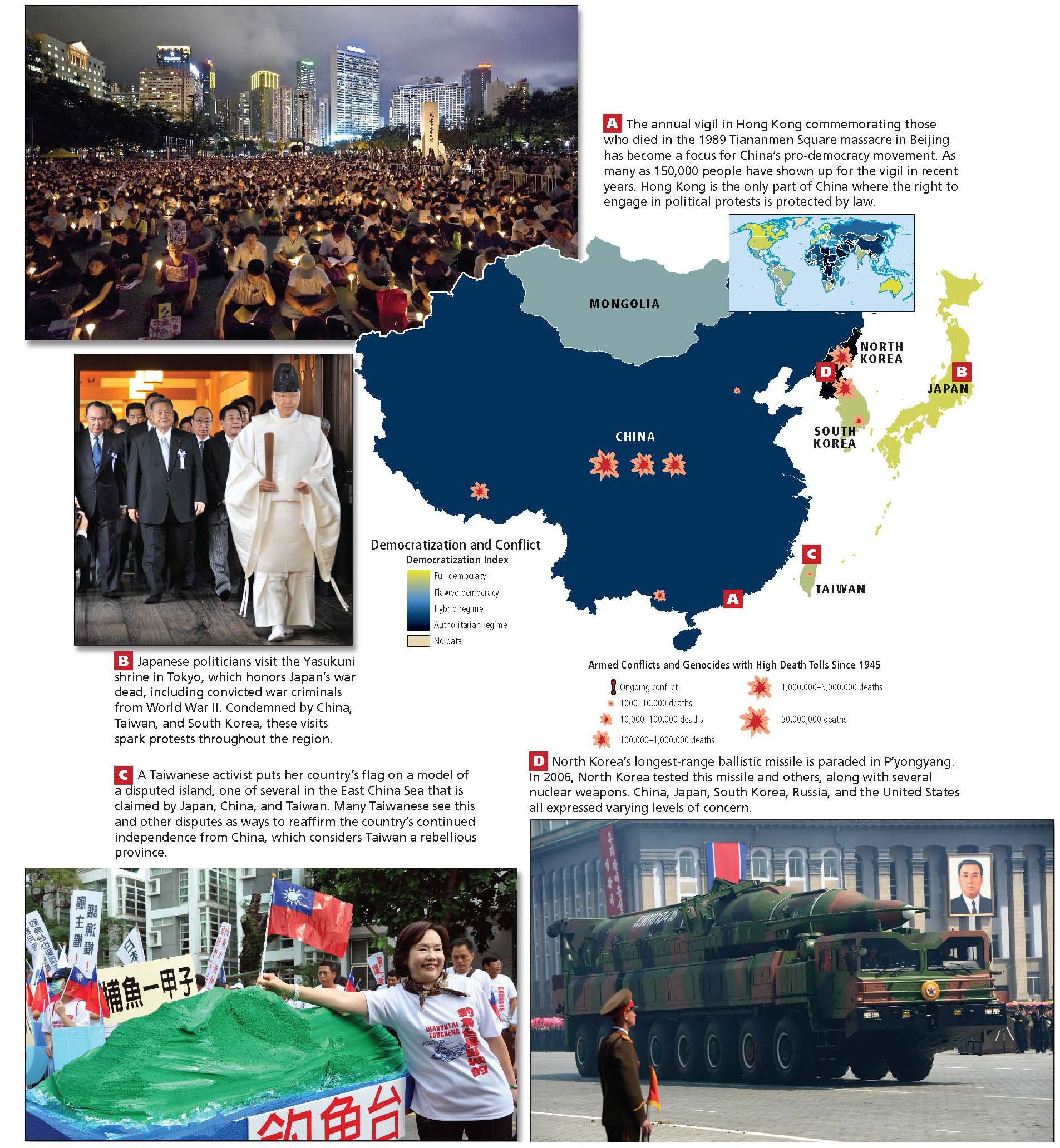

The demand for greater political freedom is growing throughout East Asia. Japan’s current political structure was established after World War II, South Korea’s in the late 1980s, and Taiwan’s in the mid-1990s. All have steadily expanded political freedoms since their inception. Mongolia has had a dramatic expansion of political freedom since abandoning socialism in 1992. China, however, remains under the tight control of an authoritarian regime, and North Korea is even more tightly held. The map in Figure 9.21 shows each country’s level of democracy. The red starbursts indicate places where civil unrest has broken out since 1945.

With China now a globalized economy, many wonder how much longer the Communist Party can remain in control without instituting democratic reforms throughout the entire country. The Communist Party officially claims that China is a democracy, and indeed some elections have long been held at the village level and within the Communist Party. However, representatives to the National People’s Congress, the country’s highest legislative body, are appointed by the Communist Party elite, who maintain tight control throughout all levels of government.

The Party selected a new leadership group (the Politburo) in 2012, but radical change is unlikely in the near future. Nevertheless, most experts on China agree that a steady shift toward greater political freedom is underway. This change might be inevitable as the population becomes more prosperous, educated, and widely traveled, thereby becoming exposed to places that have more freedom and more open government. Demands for political change built to a crescendo less than a decade after market reforms began, culminating in a series of pro-democracy protests that drew hundreds of thousands to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. These protests were brutally repressed, with thousands (the precise number is uncertain) of students and labor leaders massacred by the military. The Tiananmen Square event made clear that China’s integration into the global economy will take place on political terms dictated by the state. Since then, pressure for change has continued to mount both within China (see Figure 9.21A) and internationally, but it seems that the link between economic development and democratization is only tenuous.

International Pressures

Informed consumers and environmentalists in developed countries have long criticized China for its “no holds barred” pursuit of economic growth. Much of China’s growth has been built on environmentally destructive activities and harsh conditions for workers, both of which effectively lower production costs so that the prices of goods can be globally competitive. The pressure for political change grew, though, once China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 because its WTO membership meant that the Chinese government could no longer dictate economic policy to the same degree that it had in the past, even though the WTO does not enforce environmental and labor standards.

The 2008 Olympics in Beijing highlighted a number of issues that have also created an impetus for increasing democracy. Before the games, the international media shined its spotlight on human rights abuses of workers, protesters, prisoners, ethnic minorities such as Tibetans and Uygurs, and spiritual groups. The most prominent of such groups is Falun Gong, a Buddhist-inspired movement that has been perceived as a threat by the Chinese government because of its independence and capacity to mount a global media campaign for its cause. The extravagance of the 2008 Olympics also became a subject of criticism by the global media, with many journalists pointing out that no democracy would ever be able to devote so much tax revenue (estimated at $40 billion) to such an event, especially not in a country with as many pressing human and environmental problems as China has. Today, many of Beijing’s Olympic venues are unused; at the same time, residents have benefited from the improvements to transportation and infrastructure that were part of the Olympic rebuilding of Beijing.

211. OLYMPIC RELAY CUT SHORT BY PARIS PROTESTS

211. OLYMPIC RELAY CUT SHORT BY PARIS PROTESTS

213. BEIJING OLYMPICS: POLITICAL BATTLEGROUND?

213. BEIJING OLYMPICS: POLITICAL BATTLEGROUND?

221. REPORTS OF SALE OF EXECUTED FALUN GONG PRISONERS’ ORGANS IN CHINA CALLED “SHOCKING”

221. REPORTS OF SALE OF EXECUTED FALUN GONG PRISONERS’ ORGANS IN CHINA CALLED “SHOCKING”

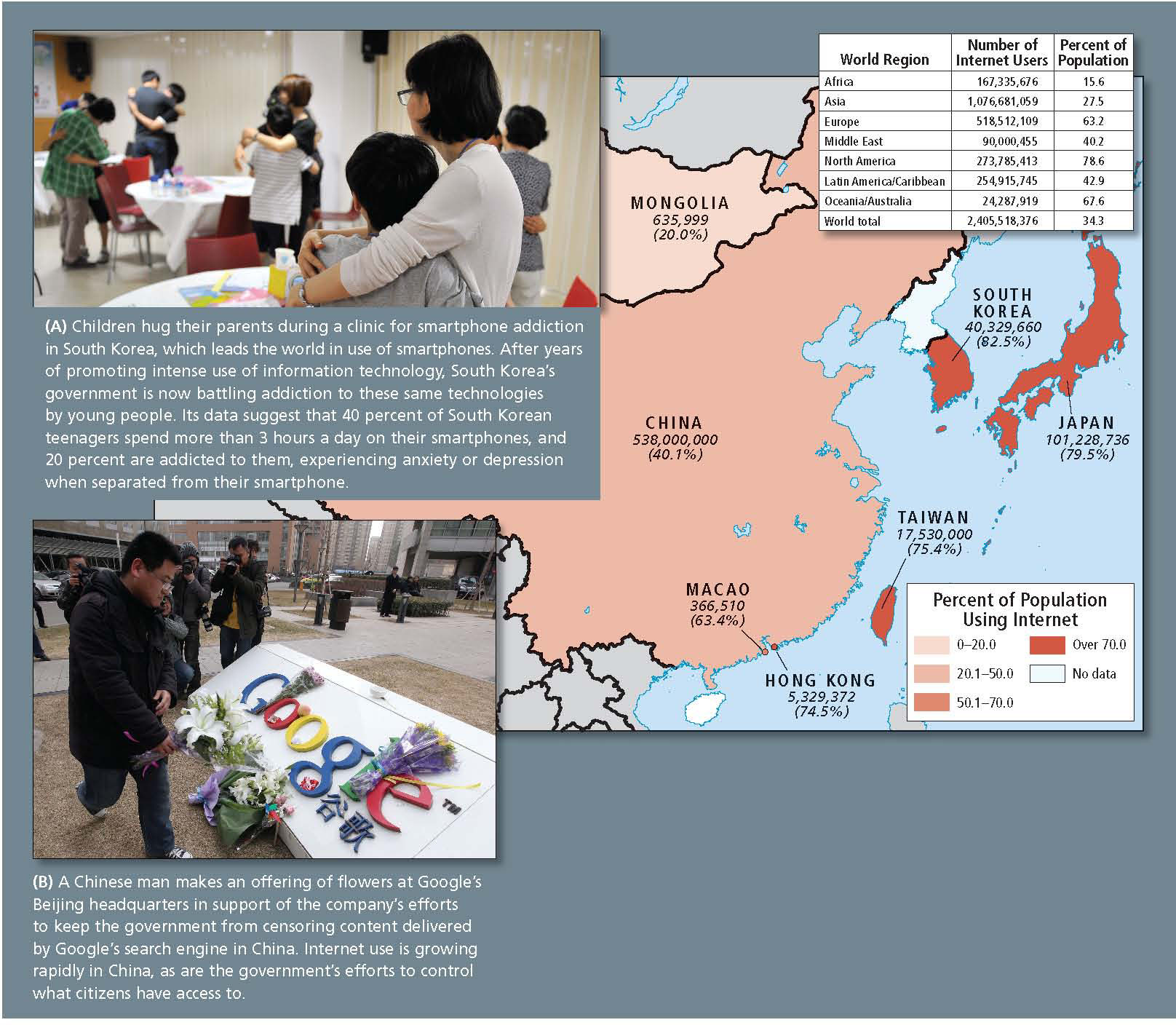

Information Technology and Political Freedom

The spread of information via the Internet has increased the push for political freedom from within China. Since the revolution in 1949, China’s central government has controlled the news media in the country. By the late 1990s, though, the expanding use of electronic communication devices was loosening central control over information. By 2001, roughly 23 million people were connected to the Internet in China; by 2012, well over 500 million (or 40 percent of the population) were connected (Figure 9.22). However, Internet access is not evenly distributed. A huge digital divide has emerged in China; there is a “connected China,” especially in large coastal cities where most people have Internet access, and a “disconnected China” in the rural interior. As development spreads, it is likely that the divide will diminish over time.

Not too long ago, telephones were very rare and people had to obtain permission to use them, but now millions of Chinese people have access to an international network of information. It is much more difficult for the government to give inaccurate explanations for problems caused by inefficiency and corruption. Journalists can now check the accuracy of government explanations by phoning witnesses or the principal actors directly and then posting their findings on the Internet. Analysts both inside and outside China see the availability of the Internet to ordinary Chinese citizens as a watershed event that supports democracy.

Nevertheless, the Internet in China is not the open forum that it is in most Western countries. Starting in 2013, Chinese Internet users are being required to register their actual names when using an online account. This is an attempt by the government to monitor speech and anonymous criticisms against party officials. And if people writing blogs in China use the words “democracy,” “freedom,” or “human rights,” they may receive the following reminder: “The title must not contain prohibited language, such as profanity. Please type a different title.” Such censorship, informally dubbed the “Great Firewall,” has been aided by U.S. technology firms such as Yahoo and Microsoft, which allow the Chinese government to use software that blocks access to certain Web sites for users in China. Google, now in dispute with the Chinese government over state-sponsored censorship, invasion of human rights activists’ email accounts, and cyber attacks, has moved operations to Hong Kong, where more freedom is allowed (see Figure 9.22B). The final chapter of Google’s Internet ideological “war” with the Chinese government over freedom of Internet access and privacy has yet to be written. Meanwhile, the Chinese company Baidu has overtaken Google as the market-leading browser in China.

Urbanization, Protests, and Technology May Enhance Political Freedom

Protests by workers for better pay and living conditions, and riots by farmers and urban dwellers displaced by new real estate developments, have exposed average citizens to the depth of dissatisfaction felt by their compatriots. China’s government reported that there were 58,000 public protests in the country in 2003. This number rose to 74,000 in 2004, and 87,000 in 2005. Since then, the government has stopped issuing complete statistics on protests. The nonprofit group Human Rights Watch estimates that approximately 100,000 to 200,000 such protests are being held each year.

People are increasingly joining interest groups that pressure the government to take action on particular problems. One of the most publicized of such groups was formed by parents whose children died after schools collapsed during a massive earthquake (which registered 7.8 on the Richter scale) in Sichuan in May 2008. They demanded changes in policies that allowed schools to be poorly constructed and pushed for compensation for their lost children. Today, the Internet has emerged as yet another tool for collective action. For example, Renren, China’s dominant social network site, has more than 150 million user accounts and has the capacity to be an instrument for community activism.

Groups that work toward gaining compensation for low pay or the loss of property are actually less threatening to the central government than those that work for political reform. In December 2008, people seeking more political freedoms signed a manifesto called the 08 Charter, calling for a decentralized federal system of government (that is, more power to the provinces), democratic elections, and the end of the Communist Party’s political monopoly. Liu Xiaobo, coauthor of the 08 Charter, was arrested, and in December 2009 he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, even as prominent international human rights activists lobbied on his behalf. In 2010, Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, though neither he nor his family was allowed to attend the ceremony in Norway.

In an effort to maintain control over China’s increasingly articulate protestors, the government has allowed elections to be held for “urban residents’ committees.” The idea seems to be to provide a peaceful outlet for voicing frustrations and creating limited change at the local level. Many of these elections are hardly democratic, with candidates selected by the Communist Party. However, in cities where unemployment is high and where protests have been particularly intense, elections tend to be more free, open, and truly democratic. It could be that interest group protests are an important first step toward actual participatory democracy, even when some, such as those who signed the 08 Charter, are harshly stifled.

Japan’s Recent Political Shifts

Significantly, the government that played such a central role during the post–World War II rise of the Japanese economy was controlled from 1955 to 2009 by one political party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). This has long led to criticism that Japan is lacking a meaningful democracy. However, in 2009, the Japanese people elected a government led by the opposition party, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), only to reverse course again and bring the LDP back to power in 2012. But no matter who is running the country, they have to deal with government debt and the prospect of cutting many social services that had supported Japan’s high standard of living. The main difference may be that the more nationalistic LDP takes a hawkish stance against China and indeed all neighboring countries (see Figure 9.21B). Having closer relations with China may be advantageous for Japan, though, as China has the potential to be a major market for Japanese exports in the future.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 4Power and Politics While radical change is unlikely in the near future, most experts on China agree that a steady shift toward greater democracy is underway. This change might be inevitable as the population becomes more prosperous, educated, and widely traveled, thereby becoming exposed to places that have more freedoms and more open government.

Geographic Insight 4Power and Politics While radical change is unlikely in the near future, most experts on China agree that a steady shift toward greater democracy is underway. This change might be inevitable as the population becomes more prosperous, educated, and widely traveled, thereby becoming exposed to places that have more freedoms and more open government. By 2012, China had 500 million people using the Internet, representing 40 percent of the country’s population. China has strict controls on Internet access and use, but social networking is emerging as a tool to promote democracy.

By 2012, China had 500 million people using the Internet, representing 40 percent of the country’s population. China has strict controls on Internet access and use, but social networking is emerging as a tool to promote democracy. Chinese citizens who share a grievance against the government are increasingly cooperating with one another in their protests. In December 2008, a manifesto for change, the 08 Charter, was signed and submitted to the government by 350 protestors.

Chinese citizens who share a grievance against the government are increasingly cooperating with one another in their protests. In December 2008, a manifesto for change, the 08 Charter, was signed and submitted to the government by 350 protestors. In Japan, one political party has controlled the government for all but 3 years since 1955, leading to criticism that Japan lacks a vigorous democracy.

In Japan, one political party has controlled the government for all but 3 years since 1955, leading to criticism that Japan lacks a vigorous democracy.