Sociocultural Issues

East Asia’s economic progress has led to social and cultural change throughout the region. Population growth, long a dominant issue, has slowed, while other demographic issues are coming to the fore. Modernized economies that bear some features of capitalism are changing work patterns and family structures.

Population Patterns

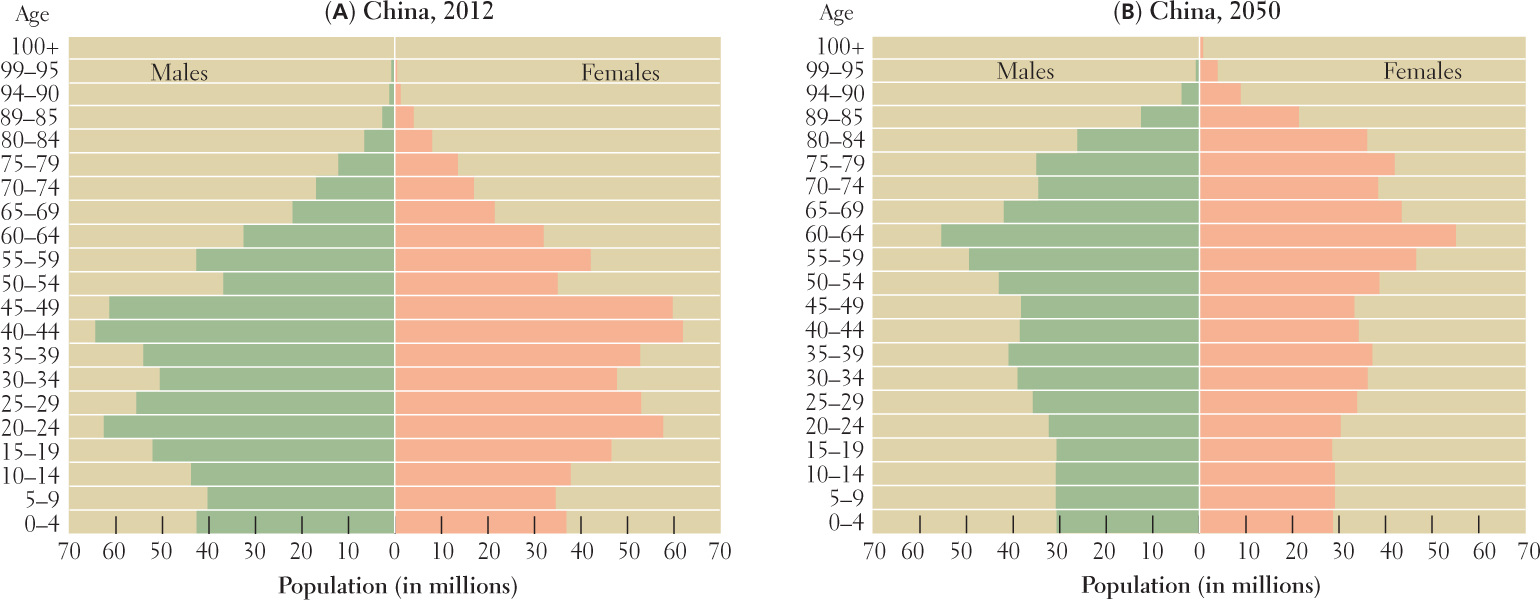

Although East Asia remains the most populous world region, families there are having many fewer children than in the past. Of all world regions, only Europe has a lower rate of natural increase (0.0 percent increase per year, compared to East Asia’s 0.4 percent). In China, this is partially due to government policies that harshly penalize families for having more than one child. But in China as well as elsewhere, urbanization and changing gender roles are also resulting in smaller families, regardless of official policy. Only in the two poorest countries—Mongolia (with 2.9 million people) and North Korea (with 24.6 million)—are women still averaging two or more children each, but even there family size is shrinking.

Responding to an Aging Population

Low birth rates mean that fewer young people are being added to the population, and improved living conditions mean that people are living longer across East Asia. The overall effect is that the average age of the populations is rising. Put another way, populations are aging. For Mongolia, South Korea, North Korea, and Taiwan, it will be several decades before the financial and social costs of supporting numerous elderly people will have to be addressed. China faces especially serious future problems with elder care because the one-child policy and urbanization have so drastically reduced family kin-groups. Japan, on the other hand, has already been dealing with the problem of having a large elderly population that requires support and a reduced number of young people to do the job.

Japan’s Options

Japan’s population is growing slowly and aging rapidly, raising concerns about economic productivity and humane ways to care for dependent people. The demographic transition is well underway in this highly developed country, where 86 percent of the population live in cities. Japan has a negative rate of natural increase (−0.2), the lowest in East Asia and on par with that of Europe. If this trend continues, Japan’s population is projected to plummet from the current 128 million to 95.5 million by 2050.

507

At the same time, the Japanese have the world’s longest life expectancy, at 83 years (Figure 9.23). As a result, Japan also has the world’s oldest population, 24 percent of which is over the age of 65. By 2055, this age group will account for approximately 40 percent of the population. By 2050, Japan’s labor pool could be reduced by more than a third, but it would still need to produce enough to take care of more than twice as many retirees as it does now. Clearly, these demographic changes will have a momentous effect on Japan’s economy, and the search for solutions is underway. One possibility is increasing immigration to bring in younger workers who will fill jobs and contribute to the tax rolls, as the United States and Europe have done. Another is to keep the elderly fit so they can work if necessary and take care of themselves.

In Japan, recruiting immigrant workers from other countries is a very unpopular solution to the aging crisis. Many Japanese people object to the presence of foreigners, and the few small minority populations with cultural connections to China or Korea have long faced discrimination. The children of foreigners born in Japan are not granted citizenship, and some who have been in the country for generations are still thought of as foreign. Today, immigrants must carry an “alien registration card” at all times.

Nonetheless, foreign workers are dribbling into Japan in a multitude of legal and illegal ways. Many are “guest workers” from South Asia brought in to fill the most dangerous and lowest-paying jobs, with the understanding that they will eventually leave. Others are the descendants of Japanese people who once migrated to South America (Brazil and Peru). Regardless, Japan’s foreign population remains tiny, making up only 1.7 percent (2.2 million people) of the total population. A recent UN report estimates that Japan would have to admit more than 640,000 immigrants per year just to maintain its present workforce and avoid a 6.7 percent annual drop in its GDP.

In a novel approach to Japan’s demographic changes, the government has invested enormous sums of money in robotics over the past decade. Robots are already widespread in such Japanese industries as auto manufacturing, and their industrial use is growing. Now they are also being developed to care for the elderly, to guide patients through hospitals, to look after children, and even to make sushi. By 2025, the government plans to replace up to 15 percent of Japan’s workforce with robots.

China’s Options

The proportion of China’s population over 65 is now only 9 percent, but this will change rapidly as conditions improve and life expectancies increase by 5 to 10 years to become more like those in China’s affluent East Asian neighbors. However, a crisis in elder care is already upon China for two other reasons: the high rate of rural-to-urban migration and the shrinkage of family support systems because of the one-child policy (discussed below).

When hundreds of millions of young Chinese were lured into cities to work, most thought rural areas would benefit from remittances, and this has happened. However, few anticipated that the one-child family would mean that for every migrant, two aging parents would be left to fend for themselves, often in rural, underdeveloped areas. China’s parliament passed a law in 2013 that requires family members to visit and support their elderly relatives. While such a law may be unenforceable, it shows how worried the government is about the social consequences of the prospect of an aging society, including the increasing spatial mismatch between the elderly who need care and their younger relatives who often have moved elsewhere in search of employment. At the same time, individual Chinese people are being proactive: few outsiders realize that the throngs of elderly Chinese people who exercise in public parks are part of a movement to keep the elderly fit that is linked to far-sighted policies aimed at lowering the costs of supporting the aged.

China’s One-Child Policy

Geographic Insight 5

Population and Gender: China’s “one-child policy” has created a shortage of females. Long-standing cultural preferences for male children mean that if their one child will be female, many parents choose abortion or put the baby up for adoption. The shortage of females is accentuated by the fact that many women are deciding to have a career rather than to marry and have children.

In response to fears about overpopulation and environmental stress, China has had a one-child-per-family policy since 1979, when it also instituted broader economic reforms. The policy is enforced with rewards for complying and with large fines for not complying. As a result, China’s rate of natural increase (0.5 percent) is the same as that of the United States, and less than half the world average (1.2 percent). If the one-child family pattern continues, China’s population will start to shrink sometime between 2025 and 2050 (Figure 9.24B), creating many of the same economic and social problems that Japan is now facing. For example, China’s working-age population will not expand much in the future. It is possible that further mechanization of Chinese agriculture will enable rural workers to shift to urban jobs, but with a limited supply of workers, employers may end up raising wages in order to compete for employees, which could diminish China’s competitive advantage in global manufacturing.

508

The one-child policy has also transformed Chinese families and Chinese society at large. For example, an only child has no siblings, so within two generations, the kinship categories of brother, sister, cousin, aunt, and uncle have disappeared from most families, meaning that any individual has very few, if any, related age peers with whom to share family responsibilities. The effect on society of the one-child family is that most children are doted on by several adults, and children are not taught by siblings to share. Conscious efforts must be made to instill self-sufficiency in only children. The one-child policy has sometimes been enforced brutally. In various times and places, the government has waged a campaign of forced sterilizations and forced abortions for mothers who already have one child.

Cultural Preference for Sons: Missing Females and Lonely Males

The prospect of a couple’s only child being a daughter, without the possibility of having a son in the future, is the aspect of the one-child policy that has caused families the most despair. For years, the makers of Chinese social policy have sought to eliminate the old Confucian-based preference for males by empowering women economically and socially. In many ways, the policy makers are succeeding in empowering young women. For example, Chinese women participate to a high degree in the workforce. Nevertheless, the preference for sons persists.

The population pyramid in Figure 9.24A illustrates the extent to which the preference for sons has created a gender imbalance in China’s population. The normal sex ratio at birth is 105 boys to 100 girls, which evens out by the age of 5. In China, however, there are 113 boys for every 100 girls born. In fact, for nearly every category until age 70, males outnumber females. The census data show that there are already 50 million more men than women. What happened to the missing girls?

There are several possible answers. Given the preference for male children, the births of these girls may simply have gone unreported as families hoped to conceal their daughter and try again for a son. There are many anecdotes of girls being raised secretly or even disguised as boys. Also, adoption records indicate that girls are given up for international adoption much more often than boys are. Or the girls may have died in early infancy, either through neglect or infanticide. Finally, some parents have access to medical tests that can identify the sex of a fetus. There is evidence that in China, as elsewhere around the world, some of these parents choose to abort a female fetus.

The cultural preference for sons persists elsewhere in East Asia as well. A deficit of girls appears on the 2000 population pyramids for Japan, the Koreas, Mongolia, and Taiwan. Nonetheless, evidence shows that attitudes may be changing. In Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia, the percentage of women receiving secondary education equals or exceeds that of men.

A Shortage of Brides

A major side effect of the preference for sons is that there is now a growing shortage of women of marriageable age throughout East Asia. China alone had an estimated deficit of 11 million women aged 20 to 35 in 2012. Females are also effectively “missing” from the marriage rolls because many educated young women are too busy with career success to meet eligible young men.

Research suggests that at least 10 percent of young Chinese men will fail to find a mate; and poor, rural, uneducated men will have the greatest difficulty. The shortage of women will lower the birth rate yet further, which will contribute to the expected shrinkage of the population over the next century. When single men age, without spouses, children, or even siblings, there will be no one to care for them. Furthermore, China’s growing millions of single young men are emerging as a threat to civil order, as they may be more prone to drug abuse, violent crime, HIV infection, and sex crimes. Cases of kidnapping and forced prostitution of young girls and women are already increasing.

509

Population Distribution

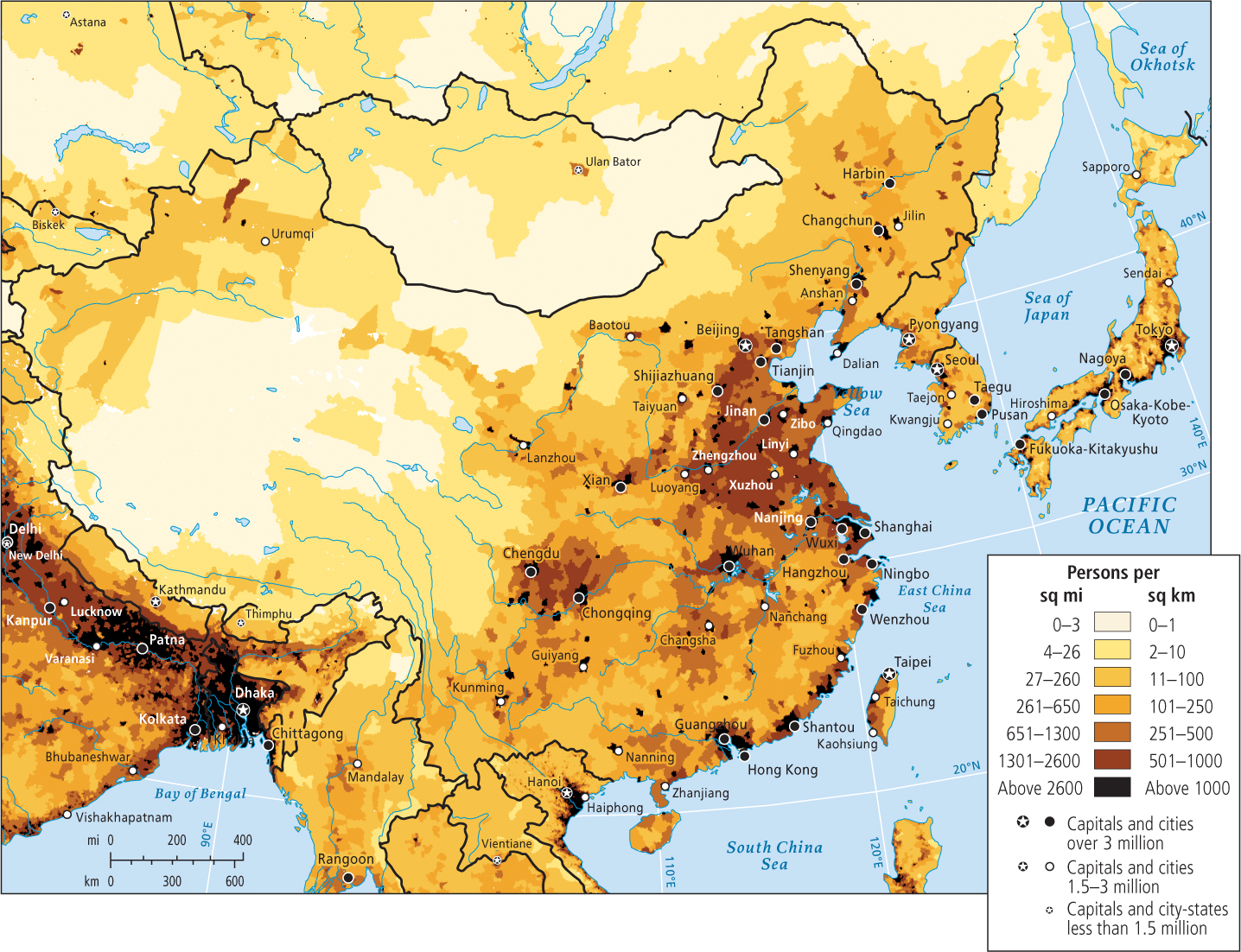

In East Asia, people are not evenly distributed on the land (Figure 9.25). Mongolia is only lightly settled, with one modest urban area. China, with 1.35 billion people, has more than one-fifth of the world’s population. However, 90 percent of these people are clustered on the approximately one-sixth of the total land area that is suitable for agriculture, and roughly half of these live in urban areas. People are concentrated especially densely in the eastern third of China: in the North China Plain, the coastal zone from Tianjin to Hong Kong that includes the delta of the Zhu Jiang (Pearl River) in the southeast, the Sichuan Basin, and the middle and lower Chang Jiang (Yangtze) basin.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Changes in the One-Child Policy?

Recently, some officials in China have supported abolishing the one-child policy, or adopting a two-child policy. Enforcement of the one-child policy is already lax in rural areas, and many ethnic minorities have long been exempt. Given China’s growing urban populations, which face numerous pressures for small families, it is unlikely that abandoning the one-child policy would produce a population boom.

The west and south of the Korean Peninsula are also densely settled, as are northern and western Taiwan. In Japan, settlement is concentrated in a band that stretches from the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama on the island of Honshu, south through the coastal zones of the Inland Sea to the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu. This urbanized region is one of the most extensive and heavily populated metropolitan zones in the world, accommodating 86 percent of Japan’s total population. The rest of Japan is mountainous and more lightly settled.

510

Human Well-Being

“The objective of development is to create an enabling environment for people to enjoy long, healthy and creative lives.”

Mahbub ul Haq, Founder of the UN Human Development Report

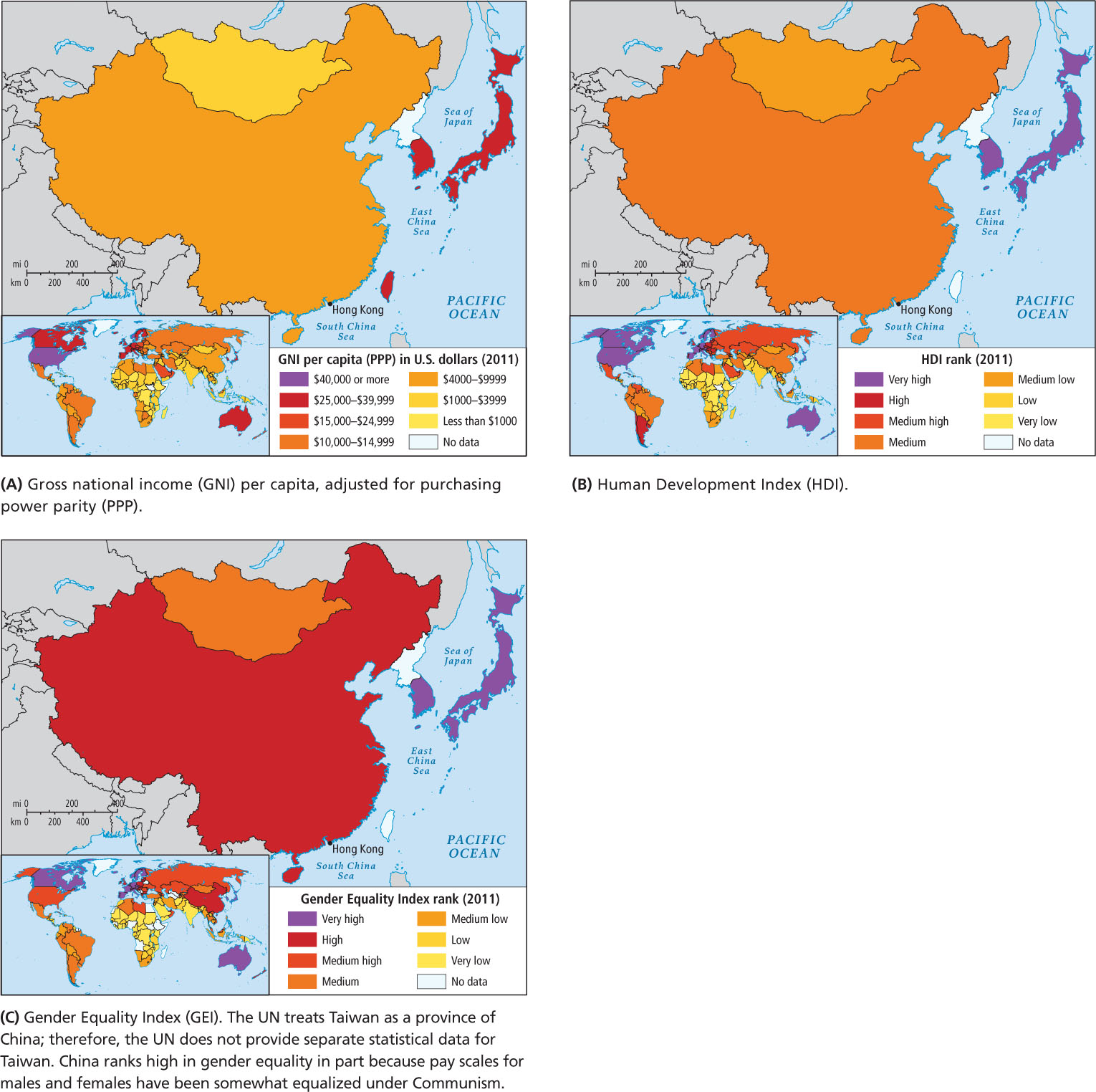

The best ways to measure how well specific countries enable their citizens to enjoy healthy and rewarding lives is disputed, but it is generally agreed that income per capita should not be the sole measure of well-being. In addition to gross national income (GNI) per capita (which is a variation of GDP), we include here maps on human development and on gender equality (Figure 9.26). On all maps, Japan and South Korea (plus Taiwan in Map A) stand out as quite different from China and Mongolia. (Taiwan is not covered in Maps B and C because in UN data, Taiwan is included with China). North Korea is not included on any of the maps because it does not submit data to the UN.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all have high GNI per capita, adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) (see Figure 9.26A). China has medium-low, and Mongolia low, GNI per capita (PPP). What the income figures mask is the extent to which there is disparity of wealth in a country. Ironically, wealth disparity in Communist-governed China is larger than elsewhere in the region. The introduction of a market economy during the last few decades has increased inequalities between individuals and between regions within China. In contrast, both South Korea and, to an even greater degree, Japan are characterized by a relatively equitable distribution of economic resources.

Figure 9.26B depicts countries’ rank on the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a calculation (based on adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment) of how adequately a country provides for the well-being of its citizens. Again, there are stark differences between the very high global ranking for Japan (15) and that for South Korea (12), and the medium to medium-low global rankings for China (101) and Mongolia (110). Still, China and Mongolia have made significant progress over the last 20 years. Both countries say that their specific goals now are to provide equitable access to basic services for all of their people, so these rankings should improve in the years to come.

511

Figure 9.26C shows how well countries are ensuring gender equality in three categories: reproductive health, political and education empowerment, and access to the labor market. A high rank indicates that the genders are tending toward equality. Again, the more developed Japan and South Korea rank very high, which indicates that gender equality in both countries is well developed relative to the rest of the world. While China and Mongolia do not rank as high, it is worth noting that they rank higher in measures of gender equality than they do in GNI and HDI. China had a high gender ranking in 2013 and Mongolia a medium ranking. This may be a result of the emphasis on gender equity under communism and, in the case of Mongolia, traditional cultural attitudes that promote some measures of gender equality.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

More people live in East Asia than in any world region, but population growth is now slowing as family size decreases. Most of the region now faces the challenge of caring for large elderly populations.

More people live in East Asia than in any world region, but population growth is now slowing as family size decreases. Most of the region now faces the challenge of caring for large elderly populations. The Japanese have the world’s longest life expectancy, at 83 years, and the world’s oldest population—24 percent of Japanese people are over the age of 65. By 2055, this age group is projected to account for 40 percent of the population.

The Japanese have the world’s longest life expectancy, at 83 years, and the world’s oldest population—24 percent of Japanese people are over the age of 65. By 2055, this age group is projected to account for 40 percent of the population. _div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Population and Gender China is grappling with an unexpected consequence of its one-child-per-family policy: a shortage of women. It is also struggling with the demise of sibling relationships and the extended family.

_div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Population and Gender China is grappling with an unexpected consequence of its one-child-per-family policy: a shortage of women. It is also struggling with the demise of sibling relationships and the extended family. The level of gender equality is relatively high in East Asia, especially in affluent countries such as Japan and South Korea.

The level of gender equality is relatively high in East Asia, especially in affluent countries such as Japan and South Korea.

Cultural Diversity in East Asia

Most countries in East Asia have one dominant ethnic group, but all countries have considerable cultural diversity. In China, for example, 93 percent of Chinese citizens call themselves “people of the Han.” The name harks back about 2000 years to the Han empire, but it gained currency only in the early twentieth century, when nationalist leaders were trying to create a mass Chinese identity. The term Han simply connotes people who share a general way of life and pride in Chinese culture. The main language spoken by the Han is Mandarin, although it is only one of many Chinese dialects.

China’s non-Han minorities number about 117 million people in more than 55 different ethnic or culture groups scattered across the country. Most live outside the Han heartland of eastern China (Figure 9.27). Some of these areas have been designated autonomous regions, where minorities theoretically manage their own affairs. In practice, however, the Communist Party in Beijing controls the fate of these regions, especially those considered to be security risks and those that have resources of economic value. We profile a few of China’s ethnic groups here.

Western China’s Muslims

Muslims of various ethnic origins have long been prominent minorities in China. All are originally of Central Asian origin; most are Turkic people who historically have been nomadic herders. Others specialized in trading. They tend to be concentrated in China’s northwest and to think of themselves as quite separate from mainstream China.

Uygurs (pronounced WEE-gurs) and Kazakhs, who are Turkic-speaking Muslims, live in the autonomous region of Xinjiang in the far northwest (see the Figure 9.1 map and Figure 9.27). Traditionally, they were nomadic herders, and some still are. The culture of western China’s minorities is related to people in elsewhere in Central Asia. Contact among these groups has been revived since China’s market reforms began and the Soviet Union dissolved (Figure 9.28). The Beijing government, on the other hand, claims this area’s oil, other mineral resources, and irrigable agricultural land for national development. Accordingly, it has sent troops and by now many millions of Han settlers to Xinjiang through what is known as the “Go West” policy. The Han settlers fill most managerial jobs in the bureaucracy, in mineral extraction, the military, and power generation. An important secondary role of the Han is to dilute the power of Uygurs and Kazakhs within their own lands. In Xinjiang, there are now almost as many Han as Uygurs (8 versus 9 million), plus small numbers of other minorities.

512

The Beijing government has rushed to develop Xinjiang and its capital Urumqi with special development zones (ETDZs), but the Uygurs have been left out of most policy-making roles and indeed have been excluded from participating in the economic boom. For example, one young Uygur man in Urumqi writes of his discontent: “I am a strong man, and well-educated. But [Han] Chinese firms won’t give me a job. Yet go down to the railroad station and you can see all the [Han] Chinese who’ve just arrived. They’ll get jobs. It’s a policy to swamp us.”

Until recently, the Uygur people of Xinjiang expressed their resistance to Han dominance merely by reinvigorating their Islamic culture. Islamic prayers were increasingly heard publicly, more Muslim women were wearing Islamic dress, Uygur was spoken rather than Chinese, and Islamic architectural traditions were being revived. Then, more active resistance groups, formed by Uygur separatists, began carrying out attacks on Chinese targets. In 2009, violence erupted in the streets of Urumqi between Uygurs and the Han and about 200 people were killed. The Beijing government responded by harshly punishing the rioters and broadcasting the accusation that all Uygur separatists, even those committed to nonviolence, are Islamic fundamentalists bent on terrorism. In 2013, China’s government began arresting nonviolent Uygur Internet-based activists.

Distinct from the Uygurs and Kazakhs are the Hui, who altogether number about 10 million. The original Hui people were descended from ancient Turkic Muslim traders who traveled the Silk Road from Europe across Central Asia to Kashgar (now Kashi) and on to Xian in the east (see the map of the Silk Road in Figure 5.9; see also Figure 9.28). Subgroups of Hui live in the Ningxia Huizu Autonomous Region and throughout northern, western, and southwestern China. There they continue as traders, farmers, and artisans. The long tradition of commercial activity and adoption of the Chinese language among the Hui has facilitated their success in China. Many are active in the new free market economies of southeastern China as businesspeople, technicians, and financial managers, using their money not just to buy luxury goods, but also to revive religious instruction and to fund their mosques, which are now more obvious in the landscape.

The Tibetans

In contrast to the prosperous and assimilated Hui are the Tibetans, an impoverished ethnic minority of nearly 5 million individuals scattered thinly over a huge, high, mountainous region in western China. The history of Tibet’s political status vis-à-vis China is long and complex, characterized by both cordial relations and conflict. During China’s imperial era (prior to the twentieth century), Tibet maintained its own government but faced the constant threat of invasion and of Chinese meddling in its affairs. In the early 1900s, Tibet declared itself separate and free from China and conducted its affairs as an independent country. It was able to maintain this status until 1949–1950, when the Chinese Communist army “liberated” Tibet, promising a “one-country, two-systems” structure, which suggested a great deal of regional self-governance. A Tibetan uprising in 1959 led China to abolish the Tibetan government and violently reorder Tibetan society. Since the 1950s, the Chinese government has referred to Tibet as the Xizang Autonomous Region. The Chinese government suppressed Tibetan Buddhism, which is an institution that Tibetans rally behind as a symbol of independence, by destroying thousands of temples and monasteries and massacring many thousands of monks and nuns. In 1959, the spiritual and political leader of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, was forced into exile in India along with thousands of his followers.

By the 1990s, the Beijing government’s strategy was to overwhelm the Tibetans with secular social and economic modernization and with Han Chinese settlers rather than outright military force (though China maintains a military presence in Tibet). To attract trade and quell foreign criticism of its treatment of Tibetans, China is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on housing and on roads, railroads, and a tourism infrastructure that capitalizes on European and American interest in Tibetan culture. China presents its actions in Tibet as part of its overall strategy to integrate the entire country economically and socially. Schools are being built and jobs opened up to young Tibetans. A new railway link connecting Tibet more conveniently to the rest of China was completed in 2006 (Figure 9.29). The Han in Tibet see the railway as a public service that will promote Tibetan development, but Tibetan activists see it as a conveyor belt for more Han dominance over the Tibetan economy and culture.  214. TIBETAN BUDDHIST NUNS’ PROTEST SONGS BRING PUNISHMENT FROM CHINA

214. TIBETAN BUDDHIST NUNS’ PROTEST SONGS BRING PUNISHMENT FROM CHINA

Within Tibetan culture, women have held a somewhat higher position than in other cultures of East Asia. Buddhism did introduce many patriarchal attitudes to Tibet, but these did not curtail other more equitable traditions. Among nomadic herders, women could have more than one husband, just as men were free to have more than one wife; at marriage, a husband often joins the wife’s family. By comparison, Han Chinese culture has typically regarded the women of Tibet and other western minorities as barbaric precisely because their roles were not circumscribed: they were not secluded, they rode horses, they worked alongside the men in herding and agriculture, and they were assertive.

513

Indigenous Diversity in Southern China

In Yunnan Province in southern China, more than 20 groups of ancient native peoples live in remote areas of the deeply folded mountains that stretch into Southeast Asia. These groups speak many different languages, and many have cultural and language connections to the indigenous people of Tibet, Burma, Thailand, or Cambodia. Gender relations are different here than among the Han. A crucial difference may be that among several groups, most notably the Dai, a husband moves in with his wife’s family at marriage and provides her family with labor or income, which is a pattern we also noted among the Tibetans. A husband inherits from his wife’s family rather than from his birth family.

Taiwan’s Many Minorities

In Taiwan and the adjacent islands, the Han account for 95 percent of the population, but Taiwan is also home to 60 indigenous minorities. Some have cultural characteristics—languages, crafts, and agricultural and hunting customs—that indicate a strong connection to ancient cultures in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The mountain dwellers among these groups have resisted assimilation more than the plains peoples. Both groups may live on reservations set aside for indigenous minorities if they choose, but most are now being absorbed into mainstream urbanized Han-influenced Taiwanese life. The Han are themselves not homogenous in Taiwan. They are divided into subgroups based on their ancestral home in China, and the people (and their descendants) who fled to Taiwan around the time of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 are often called “mainlanders.”

514

The Ainu in Japan

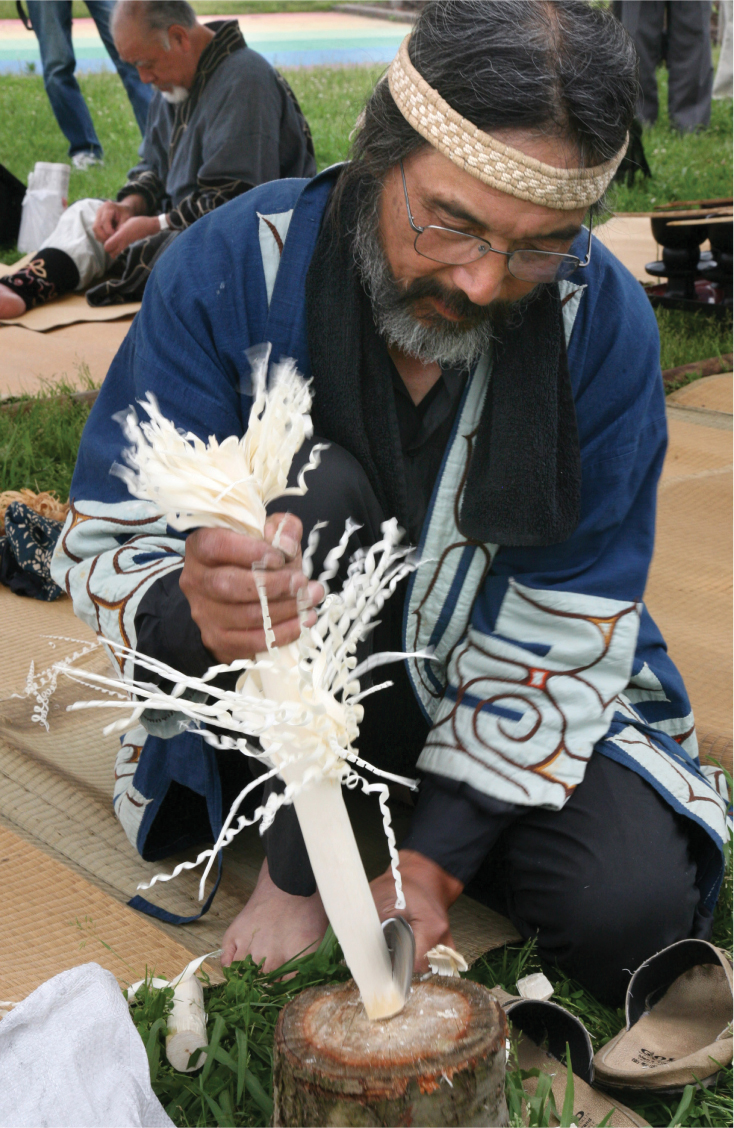

There are several indigenous minorities in Japan and most have suffered considerable discrimination. A small and distinctive minority group is the Ainu, characterized by their light skin, heavy beards, and thick, wavy hair. Now numbering only about 30,000 to 50,000, the Ainu are a racially and culturally distinct group thought to have migrated many thousands of years ago from the northern Asian steppes. They once occupied Hokkaido and northern Honshu and lived by hunting, fishing, and some cultivation, but they are now being displaced by forestry and other development activities. Few full-blooded Ainu remain because, despite prejudice, they have been steadily assimilated into the mainstream Japanese population (Figure 9.30). In 2008, the Japanese parliament, somewhat belatedly, officially recognized the Ainu as an indigenous minority.

Ainu an indigenous cultural minority group in Japan characterized by their light skin, heavy beards, and thick, wavy hair, who are thought to have migrated thousands of years ago from the northern Asian steppes

East Asia’s Most Influential Cultural Export: The Overseas Chinese

China has had an impact on the rest of the world not only through its global trade, but also through the migration of its people to nearly all corners of the world. The first recorded emigration by the Chinese took place more than 2200 years ago. Following that, China’s contacts then spread eastward to Korea and Japan, westward into Central and Southwest Asia via the Silk Road, and by the fifteenth century, to Southeast Asia, coastal India, the Arabian Peninsula, and even Africa.

Trade was probably the first impetus for Chinese emigration. The early merchants, artisans, sailors, and laborers came mainly from China’s southeastern coastal provinces. Taking their families with them, some settled permanently on the peninsulas and islands of what are now Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Today they form a prosperous urban commercial class known as the Overseas Chinese. The quintessential Overseas Chinese state in Southeast Asia is Singapore, where 77 percent of the population is ethnically Chinese (see Chapter 10).

In the nineteenth century, economic hardship in China and a growing international demand for labor spawned the migration of as many as 10 million Chinese people to countries all over the world. By the middle of the twentieth century, many others fleeing the repression of China’s Communist Revolution joined those from earlier migrations despite thorough assimilation into adopted homelands. As a result, “Chinatowns” are found in most major world cities. Somewhat unfairly, the term Overseas Chinese has been extended to apply to Chinese emigrants and their descendants.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

There are several distinct minority groups in East Asia: the Uygurs, Kazakhs, and Tibetans in western China; the Hui, scattered throughout central China; and smaller indigenous groups in southern China, Taiwan, and Japan.

There are several distinct minority groups in East Asia: the Uygurs, Kazakhs, and Tibetans in western China; the Hui, scattered throughout central China; and smaller indigenous groups in southern China, Taiwan, and Japan. There is resentment and sometimes open resistance to Han Chinese domination in the various minority homelands.

There is resentment and sometimes open resistance to Han Chinese domination in the various minority homelands. Throughout East Asia, minorities have experienced discrimination.

Throughout East Asia, minorities have experienced discrimination. Millions of “Overseas Chinese” live in cities and towns around the world, especially in Southeast Asia. Most have settled permanently in these new homelands.

Millions of “Overseas Chinese” live in cities and towns around the world, especially in Southeast Asia. Most have settled permanently in these new homelands.

515