1.7 DEVELOPMENT

The economy is the forum in which people make their living, and resources are what they use to do so. Extractive resources are resources that must be mined from the Earth’s surface (mineral ores) or grown from its soil (timber and plants). There are also human resources, such as skills and brainpower, which are used to transform extractive resources into useful products (such as refrigerators or bread) or bodies of knowledge (such as books or computer software). Economic activities are often divided into three sectors of the economy: the primary sector is based on extraction (mining, forestry, and agriculture); the secondary sector is industrial production (processing, manufacturing, and construction); and the tertiary sector is services (sales, entertainment, and financial). Of late, a fourth, or quaternary sector, has been added to cover intellectual pursuits such as education, research, and IT (information technology) development. Generally speaking, as people in a society shift from extractive activities, such as farming and mining, to industrial and service activities, their material standards of living rise–

primary sector an economic sector of the economy that is based on extraction (see also extraction)

extraction mining, forestry, and agriculture

secondary sector an economic sector of the economy that is based on industrial production (see also industrial production)

industrial production processing, manufacturing, and construction

tertiary sector an economic sector of the economy that is based on services (see also services)

services sales, entertainment, and financial services

quaternary sector a sector of the economy that is based on intellectual pursuits such as education, research, and IT (information technology) development

development a term usually used to describe economic changes such as the greater productivity of agriculture and industry that lead to better standards of living or simply to increased mass consumption

The development process has several facets, one of which is a shift from economies based on extractive resources to those based on human resources. In many parts of the world, especially in poorer societies (often referred to as “underdeveloped” or “developing”), there are now shifts away from labor-

Measuring Economic Development

The most long-

gross domestic product (GDP) per capita the total market value of all goods and services produced within a particular country’s borders and within a given year, divided by the number of people in the country

Using GNI per capita as a measure of how well people are living has several disadvantages. First is the matter of wealth distribution. Because GNI per capita is an average, it can hide the fact that a country has a few fabulously rich people and a great mass of abjectly poor people. For example, a GNI per capita of U.S.$50,000 would be meaningless if a few lived on millions per year and most lived on less than $10,000 per year.

Second, the purchasing power of currency varies widely around the globe. A GNI of U.S.$18,000 per capita in Barbados might represent a middle-

purchasing power parity (PPP) the amount that the local currency equivalent of U.S.$1 will purchase in a given country

Euro zone those countries in the European Union that use the Euro currency

A third disadvantage of using GDP (PPP) or GNI (PPP) per capita is that both measure only what goes on in the formal economy—all the activities that are officially recorded as part of a country’s production. Many goods and services are produced outside formal markets, in the informal economy. Here, work is often bartered for food, housing, or services, or for cash payments made “off the books”—payments that are not reported to the government as taxable income. It is estimated that one-

formal economy all aspects of the economy that take place in official channels

informal economy all aspects of the economy that take place outside official channels

There is a gender aspect to informal economies. Researchers studying all types of societies and cultures have shown that, on average, women perform about 60 percent of all the work done, and that much of this work is unpaid and in the informal economy. Yet only the work women are paid for in the formal economy appears in the statistics, so economic figures per capita ignore much of the work women do. Statistics also neglect the contributions of millions of men and children who work in the informal economy as subsistence farmers, traders, service people, or seasonal laborers.

A fourth disadvantage of GDP (PPP) and GNI (PPP) per capita is that neither takes into consideration whether these levels of income are achieved at the expense of environmental sustainability, human well-

Geographic Patterns of Human Well-Being

Some development experts, such as the Nobel Prize–

human well-

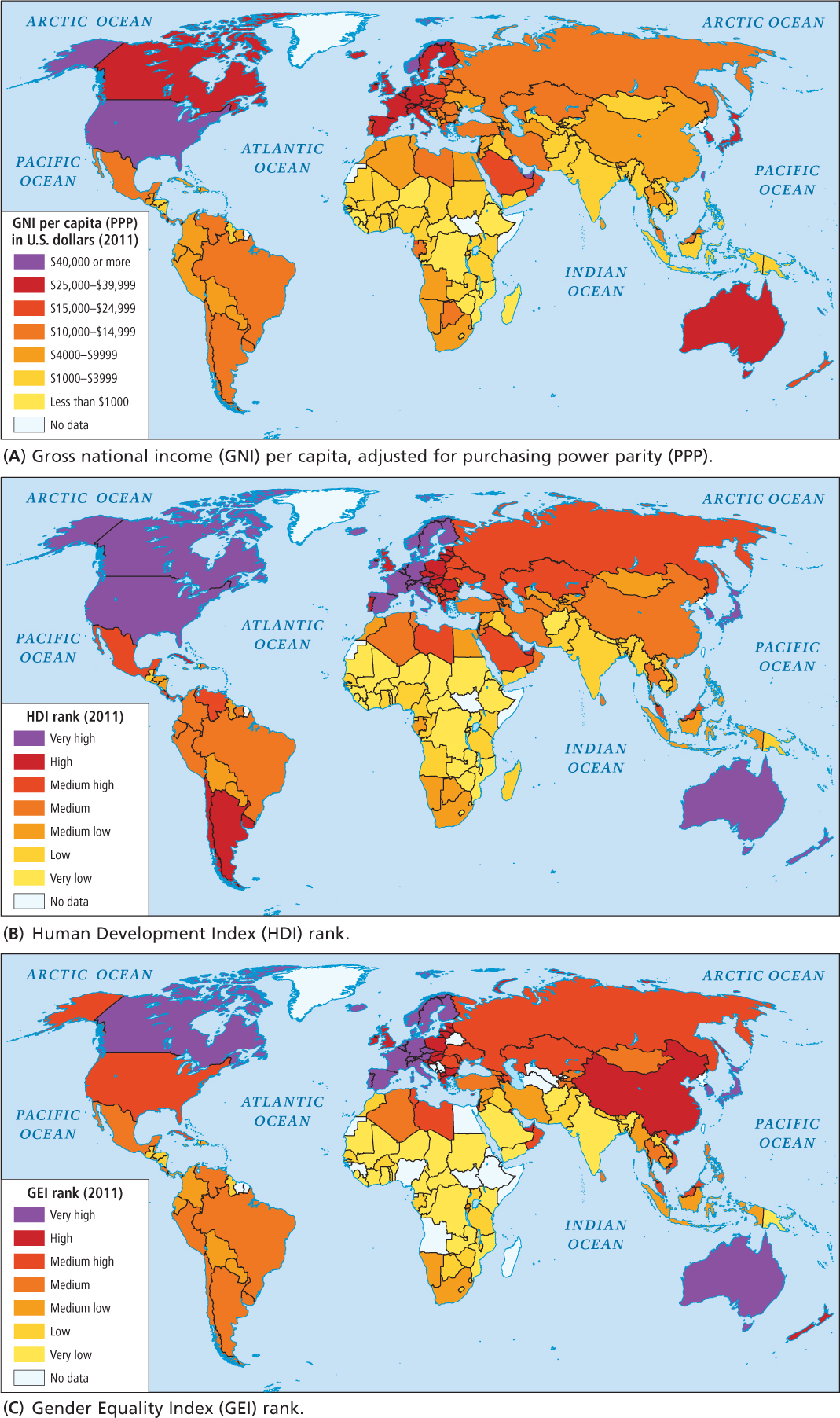

Global GNI per capita (PPP) is mapped in Figure 1.21A. Comparisons between regions and countries are possible, but as discussed above, GNI per capita figures ignore all aspects of development other than economic ones. For example, there is no way to tell from GNI per capita figures how quickly a country is consuming its natural resources, or how well it is educating its young, maintaining its environment, or seeking gender and racial equality. Therefore, along with the traditional GNI per capita figure, geographers increasingly use several other measures of development.

The second measure used in this book is the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), which calculates a country’s level of well-

United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) an index that calculates a country’s level of well-

The third measure of well-

United Nations Gender Equality Index rank (GEI) a composite measure reflecting the degree to which there is inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment, and the labor market. A high rank indicates that the genders are tending toward equality

Together, these three measures reveal some of the subtleties and nuances of well-

A geographer looking at these maps might make the following observations:

The map of GNI per capita figures (see Figure 1.21A) shows a wide range of difference across the globe, with very obvious concentrations of high and low GNI per capita. The most populous parts of the world—

China and India— have medium- low and low GNI, respectively, and sub- Saharan Africa has the lowest. The HDI rank map (see Figure 1.21B) shows a similar pattern, but look closely. Middle and South America, Southeast Asia, China, Italy, and Spain rank a bit higher on HDI than they do on GNI; several countries in southern Africa, as well as Iran, rank lower on HDI than on GNI, thus illustrating the disconnect between GNI per capita and human well-

being. The map of GEI rank (see Figure 1.21C) shows some strange anomalies, with certain high-

income countries, such as the United States (medium high) and Saudi Arabia (very low), ranking far lower on this index than on HDI. Meanwhile, China (high), which has a reputation for gender discrimination and a medium- low GNI, ranks higher than the United States on the GEI scale, in the same category with New Zealand and Ireland.

Sustainable Development and Political Ecology

The United Nations (UN) defines sustainable development as the effort to improve current living standards in ways that will not jeopardize those of future generations. Sustainability has only recently gained widespread recognition as an important goal—

sustainable development the effort to improve current standards of living in ways that will not jeopardize those of future generations

Geographers who study the interactions among development, politics, human well-

political ecologists geographers who study the interactions among development, politics, human well-

Political ecologists are raising awareness that development should be measured by the improvements brought to overall human well-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The term development has until recently referred to the rise in material standards of living that usually accompanies the shift from extractive economic activities, such as farming and mining, to industrial and service economic activities.

Measures of development are being redefined to mean improvements in overall average well-

being and progress in overall environmental sustainability. For development to happen, social services, such as education and health care, are necessary to enable people to contribute to economic growth.

It is estimated that one-

third or more of the world’s work takes place in the informal economy, where work is often bartered for food, housing, or services, or for cash payments made “off the books” that are not reported to the government as taxable income.