2.7 RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES

Citizens of Canada and the United States share many characteristics and concerns. Indeed, in the minds of many people—

Asymmetries

Asymmetry means “lack of balance.” Although the United States and Canada occupy about the same amount of space (Figure 2.19), much of Canada’s territory is cold and sparsely inhabited. The U.S. population is about ten times the Canadian population. While Canada’s economy is one of the largest and most productive in the world, producing U.S.$1.4 trillion (PPP) in goods and services in 2011, it is dwarfed by the U.S. economy, which is more than ten times larger, at $15.04 trillion (PPP) in 2011.

In international affairs, Canada quietly supports civil society efforts abroad, while the United States is an economic, military, and political superpower preoccupied with maintaining its role as a world leader. In framing foreign affairs policy, the United States regards Canada’s position only as an afterthought, in part because the country is such a secure ally. But managing its relationship with the United States is a top foreign policy priority for Canada. As former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau once told the U.S. Congress, “Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant: No matter how friendly and even-

Similarities

Notwithstanding the asymmetries, the United States and Canada have much in common. Both are former British colonies and have retained English as the dominant language. Both also experienced settlement and exploration by the French. From their common British colonial experience, they developed comparable democratic political traditions. Both are federations (of states or provinces), and both are representative democracies, with similar legal systems.

Not the least of the features they share is a 4200- 42. U.S. BORDER SECURITY REPORT

42. U.S. BORDER SECURITY REPORT

Canada and the United States share many other landscape similarities. Their cities and suburbs look much the same. The billboards that line their highways and freeways advertise the same brand names. Shopping malls and satellite business districts have followed suburbia into the countryside, encouraging comparable types of mass consumption and urban sprawl. The two countries also share similar patterns of ethnic diversity that developed in nearly identical stages of immigration from abroad.

Democratic Systems of Government: Shared Ideals, Different Trajectories

Canada and the United States have similar democratic systems of government, but there are differences in the way power is divided between the federal government and provincial or state governments. There are also differences in the way the division of power has changed since each country became independent.

Both countries have a federal government in which a union of states (United States) or provinces (Canada) recognizes the sovereignty of a central authority, while states/provinces and local governments retain many governing powers. In both Canada and the United States, the federal government has an elected executive branch, elected legislatures, and an appointed judiciary. In Canada, the executive branch is more closely bound to follow the will of the legislature. At the same time, the Canadian federal government has more and stronger powers (at least constitutionally) than does the U.S. federal government.

Over the years, both the Canadian and U.S. federal governments have moved away from the original intentions of their constitutions. Canada’s initially strong federal government has become somewhat weaker, largely in response to demands by provinces, such as the French-

The more limited federal government that the United States had at its outset has expanded its powers. The U.S. federal government’s original source of power was its mandate to regulate trade between states. Over time, this mandate has been interpreted ever more broadly. Now the U.S. federal government has a powerful effect on life even at the local level, primarily through its ability to dispense federal tax monies via such means as grants for school systems, federally assisted housing, military bases, drug and food regulation and enforcement, urban renewal, and the rebuilding of interstate highways. Money for these programs is withheld if state and local governments do not conform to federal standards. This practice has made some poorer states dependent on the federal government. However, it has also encouraged some state and local governments to enact more enlightened laws than they might have done otherwise. For example, in the 1960s the federal government promoted civil rights for African American citizens by requiring states to end racial segregation in schools in order to receive federal support for their school systems.

The Social Safety Net: Canadian and U.S. Approaches

The Canadian and U.S. governments have responded differently to workers who have been displaced by economic change. Ultimately, these differences derive from prevailing political positions and widely held notions each country has about what the government’s role in society should be. In Canada there is broad political support for a robust social safety net, the services provided by the government—

social safety net the services provided by the government—

For many decades, Canada has spent more per capita than the United States on social programs. These programs, especially unemployment benefits, have generally made the financial lives of working Canadians more secure. These policies also reflect the workings of Canada’s democracy; voters have supported tax hikes to fund several major expansions of the social safety net during the twentieth century.

Compared to Canada, the United States provides much less of a social safety net. For years the prevailing political argument against the expansion of the U.S. social safety net has been that the system offers lower taxes for businesses, corporations, and the wealthy, which in turn invest their surpluses in expansions or in new businesses, thus creating jobs and new taxpayers. These benefits of low taxes are assumed to trickle down to those most in need. The fit of this position with the reality of what actually happens has often been challenged, especially during times of economic recession.

Two Health-

The financial viability and medical outcomes of Obamacare are not yet known, but the most recent statistics show why change was sought. In 2012, the United States spent more per capita on health care than any other industrialized country—

|

Country |

Health care cost as a percentage of GDP |

Percentage of population with no insurance |

Deaths per 1000† |

Infant mortality per 1000 live births in 2009* |

Maternal mortality per 100,000 live births in 2008‡ |

Life expectancy at birth (years) in 2011* |

Annual health expenditures per capita (PPP U.S.$) in 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada |

10.9 |

0 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

78.5 |

$5452§ |

|

United States |

16.2 |

15.5 |

8 |

8 |

17 |

81 |

$8086** |

Sources: *United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2011 (New York: United Nations Development Programme), Tables 1, 9, and 10, at http:/

†Population Reference Bureau, 2011 World Population Data Sheet, at http:/

‡Medical News Today, “Maternal Mortality Rises in the USA, Canada and Denmark and Falls in China, Egypt, Ecuador and Bolivia,” April 13, 2010, at http:/

§News Medical, “Health Care Spending in Canada Expected to Reach $183.1 Billion in 2009: CIHI,” November 19, 2009, at http:/

**Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditure Data,” at https:/

Gender in National Politics

North America has some powerful political contradictions with regard to gender. While women voters are a potent political force, successful female politicians are not as numerous as one might expect. Women cast the deciding votes in the U.S. presidential election of 1996, voting overwhelmingly for Bill Clinton. In the 2006 interim elections, 55 percent of women voted for the Democratic Party candidates, registering strong anti-

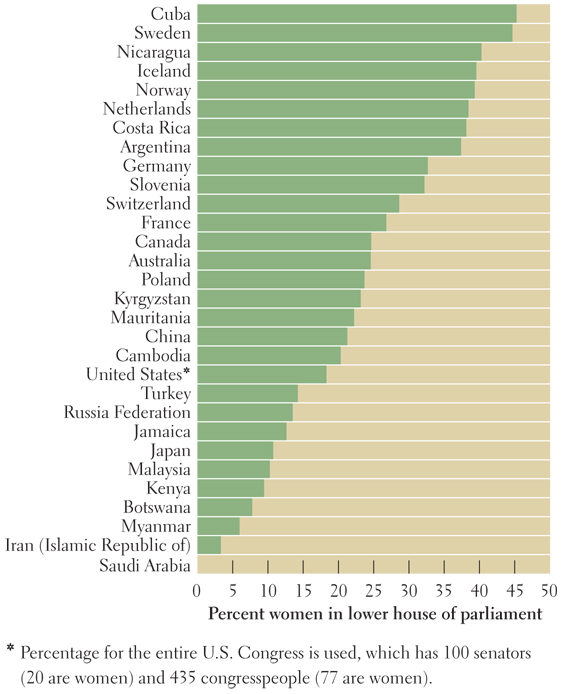

And yet in terms of electing female political leaders to office, women have not had the success warranted by their powerful role as voters. Of the 535 people in the U.S. Congress as of 2014, only 99 members, or 18.5 percent, were women. Gender equity was somewhat closer at the state level, where 24.1 percent of legislators were women as of the 2012 elections. In Canada, women have had a little more success. As of 2014, Canadian women constituted 25 percent of the House of Commons in Parliament and held 24 percent of provincial legislative seats. Neither country compares well to the world at large in that, as Figure 2.20 shows, over the last decade other countries have added substantial female representation to legislatures.

Things are somewhat more equitable for Canadian women at the executive level. In 2011, Canada elected four women as provincial governors and another as executive of the Nunavut Territory. (There are ten provinces and three territories.) After the 2012 election, the United States had 7 out of a possible 50 female governors. Canada briefly had a female prime minister in 1993. While the United States has never had a female president, in 2008, Hillary Clinton was the first woman to have a serious chance at becoming the U.S. president when she competed with Barack Obama to become the Democratic Party candidate.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics North America has relatively high levels of political freedom, though in recent decades many of its residents have become disillusioned with the political process for a variety of reasons. While Canada plays a relatively modest political role abroad, the United States has enormous influence on the global political order, although its status as the world’s predominant “superpower” is increasingly being challenged.

While an oft-

stated ideal of U.S. official foreign policy (it is less of one for Canada) is to promote democracy abroad, the actual global distribution of U.S. spending on foreign aid and military assistance indicates that U.S. strategic and economic interests take precedence over promoting democracy. Canada continues to have a more robust social safety net, including health care, than does the United States.

While women voters are a potent political force in the United States and Canada, the number of elected female politicians has not been commensurate with the percentage of women in the general population of each country.