3.5 GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: The integration of this region with the global economy has left it with the widest gap between rich and poor in the world. Long-

For decades, Middle and South America has been one of the poorer world regions—

3.5.1 ECONOMIC INEQUALITY AND INCOME DISPARITY

With the exception of a few small countries, the income disparity—the gap between rich and poor—

|

Ratio of wealth of richest 10% to poorest 10% of the population† |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Country |

HDI rank, 2001 |

1987– |

HDI rank, 2003 |

1998– |

HDI rank, 2009 |

2004– |

|

Middle and South America |

||||||

|

Bolivia |

104 |

91:1 |

114 |

25:1 |

113 |

94:1 |

|

Brazil |

69 |

49:1 |

65 |

66:1 |

75 |

41:1 |

|

Chile |

39 |

34:1 |

43 |

43:1 |

44 |

26:1 |

|

Colombia |

62 |

43:1 |

64 |

43:1 |

77 |

60:1 |

|

Guatemala |

108 |

29:1 |

119 |

29:1 |

122 |

34:1 |

|

Mexico |

51 |

26:1 |

55 |

35:1 |

53 |

21:1 |

|

Peru |

73 |

23:1 |

82 |

22:1 |

78 |

26:1 |

|

Venezuela |

61 |

24:1 |

69 |

44:1 |

58 |

19:1 |

|

Other selected countries |

||||||

|

China |

87 |

13:1 |

104 |

13:1 |

92 |

13:1 |

|

France |

13 |

9:1 |

17 |

9:1 |

8 |

9:1 |

|

Jordan |

88 |

9:1 |

90 |

9:1 |

96 |

10:1 |

|

Philippines |

70 |

16:1 |

85 |

17:1 |

105 |

14:1 |

|

South Africa |

94 |

33:1 |

111 |

65:1 |

129 |

35:1 |

|

Thailand |

66 |

12:1 |

64 |

13:1 |

87 |

13:1 |

|

Turkey |

82 |

14:1 |

96 |

13:1 |

79 |

17:1 |

|

United States |

6 |

17:1 |

7 |

17:1 |

13 |

16:1 |

*The UN used data from 1987–

†Decimals rounded up or down.

‡Survey years fall within this range.

§Ratios are from the United Nations Development Report 2009.

Sources: United Nations Human Development Report 2001, Table 12; UNHDR 2003, Table 13; UNHDR 2009, Table M.

income disparity the gap in income between rich and poor

Phases of Economic Development

The current economic and political situation in Middle and South America derives from the region’s history, which can be divided into three major phases: the early extractive phase, the import substitution industrialization (ISI) phase, and the current structural adjustment and marketization phase, which includes sharply rising investment from abroad. All three phases have helped entrench wide income disparities despite a consensus that more egalitarian development is desirable.

Early Extractive Phase From the time European conquerors first arrived, economic development was guided by a policy of mercantilism in which Europeans extracted resources and controlled much of the economic activity in the American colonies in order to increase the power and wealth of their “mother” country. Even after the colonies became independent countries, many extractive enterprises were owned by foreign investors who had few incentives to build stable local economies.

A small flow of foreign investment and manufactured goods entered the region, while a vast flow of raw materials left for Europe and beyond. The money to fund the farms, plantations, mines, and transportation systems that enabled the extraction of resources for export came from abroad, first from Europeans and later from North Americans and other international sources. One example is the still highly lucrative Panama Canal. The French first attempted to build the canal in 1880. It was later completed and run by the United States and finally turned over to Panamanian control in 1999. The profits from these ventures were usually banked abroad, depriving the region of investment funds and tax revenues that could have made it more economically independent. Industries were slow to develop in the region, so even essential items, such as farm tools and household utensils, had to be purchased from Europe and North America at relatively high prices. Many people simply did without.

A number of economic institutions arose in Middle and South America to supply food and raw materials to Europe and North America. Large rural estates called haciendas were granted to colonists as a reward for conquering territory and people for Spain. For generations these essentially feudal estates were then passed down through the families of those colonists. Over time, the owners, who often lived in a distant city or in Europe, lost interest in the day-

hacienda a large agricultural estate in Middle or South America, more common in the past; usually not specialized by crop and not focused on market production

Plantations were large factory farms. In addition to growing crops such as sugar, coffee, cotton, or (more recently) bananas, crops were often processed on site for shipment. Plantation owners made larger investments in equipment, and these farms were more efficient and profitable than haciendas. However, plantations had relatively little local economic impact. Instead of employing local populations, plantation owners imported enslaved people from Africa. The equipment that the plantations used was usually imported from Europe, which was also where plantation owners preferred to invest their profits. As a result, little money was available to support the development of local industries that could have grown up around the plantations.

plantation a large factory farm that grows and partially processes a single cash crop

First developed by the European colonizers of the Caribbean and northeastern Brazil in the 1600s, plantations became more common throughout Middle and South America by the late nineteenth century. Unlike haciendas, which were often established in the continental interior in a variety of climates, plantations were for the most part situated in tropical coastal areas with year-

As markets for meat, hides, and wool grew in Europe and North America, the livestock ranch emerged, specializing in raising cattle and sheep. Today, commercial ranches serving such global markets as the fast-

Mining was another early extractive industry (Figure 3.14). Important mines (primarily gold and silver at first) were located on the island of Hispaniola and in north-

Profits from the region’s mines, ranches, plantations, and haciendas continued to leave the region, even after the countries gained independence in the nineteenth century. One of the main reasons for this was that wealthy foreign investors retained control of many of the extractive enterprises.

Import Substitution Industrialization Phase After World War II, there were numerous political movements against the continuing domination of the economy and society by local elites and a few foreign investors. Some governments, notably those of Mexico and Argentina, tried to boost their economic independence by keeping money and resources within their borders through policies of import substitution industrialization (ISI). Subsidies, among other measures, helped support the local production of machinery and other commonly imported items.

import substitution industrialization (ISI) policies that encourage local production of machinery and other items that previously had been imported at great expense from abroad

To encourage local people to buy manufactured goods from local suppliers, governments placed high tariffs on imported, usually higher-

The state-

Not all state-

Beginning in the early 1970s, sharp increases in oil prices and decreases in global prices of raw materials ended a period of relative prosperity that had begun in the early 1950s. Reluctant to let go of the dream of rapid development, governments and private interests across the region continued to pursue ambitious plans to modernize and industrialize their national economies. They did this even as prices for raw material exports—

Structural Adjustment and the Marketization Phase Alarmed over the mounting debt of their clients, foreign banks that had made loans to governments in the region took action. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) developed and enforced policies that mandated profound changes in the organization of national economies. To ensure that sufficient money would be available to repay loans taken out from foreign banks to finance the now-

structural adjustment programs (SAPs) policies that require economic reorganization toward less government involvement in industry, agriculture, and social services; sometimes imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund as conditions for receiving loans

privatization the selling of formerly government-

marketization the development of a free market economy in support of free trade

In the case of privatization, the investors to whom government firms were sold were multinational corporations located in North America, Europe, and Asia. Thus the SAP era resulted in industries across the region being returned to foreign ownership. The other main SAP policy, marketization, required that governments remove tariffs on imported goods of all types in order to obtain further loans. The removal of tariffs then caused many local industries to fail.

Crucially, SAPs also reversed the ISI- 61. PERUVIANS STRUGGLE TO GAIN HEALTH CARE ACCESS

61. PERUVIANS STRUGGLE TO GAIN HEALTH CARE ACCESS

VIGNETTE

In August of 2003, Orbalin Hernandez returned to his self-

In 2006, Orbalin and his fellow Mexicali workers were told that their wages were too high to allow their employers to compete with companies located in China, where in 2005, workers with the same skills as Orbalin earned just $0.35 an hour. Indeed, that year, 14 Mexicali plants closed and moved to Asia. Those firms remaining in Mexicali cut wages and reduced benefits.

By 2009, it appeared that the global recession was affecting Chinese–

Though Orbalin’s salary at Thomson-

Export Processing Zones A major component of SAPs was the expansion of manufacturing industries in Export Processing Zones (EPZs), also known as free trade zones—specially created areas within a country where, in order to attract foreign-

Export Processing Zones (EPZs) specially created legal spaces or industrial parks within a country where, to attract foreign-

There are EPZs in nearly all countries on the Middle and South American mainland and on some Caribbean islands (in many other world regions also). However, the largest of the EPZs is the conglomeration of assembly factories, called maquiladoras, that are located along the Mexican side of the U.S.–Mexico border. Although these factories do provide employment, living conditions are difficult and exactly what role they will ultimately play in Mexican economic development is unclear, as the vignette above illustrates.

maquiladoras foreign-

The Backlash Against SAPs The SAP era did not produce the sustained economic growth that was expected to relieve the debt crisis and create broader prosperity. SAPs failed to stimulate economic growth in large part because they encouraged more dependence on exports of raw materials just when prices for these items were falling in the global market.

Since the late 1990s, millions of voters in Middle and South America have registered their opposition to SAPs. Starting in 1999, presidents who explicitly opposed SAPs have been elected in eight countries in the region: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Both Brazil and Argentina made considerable sacrifices to pay off their debts and liberate themselves from the restrictions of SAPs. Venezuela, under President Hugo Chávez, emerged as a leader of the SAP backlash. In 2005, the Chávez administration nationalized foreign oil companies operating in Venezuela. Since then it has also used its own considerable oil wealth to help other countries, such as Argentina, Bolivia, and Nicaragua, pay off their debts. Bolivia, led by Evo Morales (often an ally of Chávez), reversed the SAP policy of privatization by nationalizing that country’s natural gas industry. Loans taken from the IMF dropped from $48 billion in 2003 to just $1 billion in 2008. During this same period, the IMF reversed its policies from promoting SAPs to promoting Poverty Reduction Strategies Papers (PRSPs) that attempt to combine marketization with strong investment in social programs. This new IMF position has been maintained across the globe now for several years, suggesting that voters in Middle and South America have had an important impact on a major global financial institution (see Chapter 1).

nationalize to seize private property and place it under government ownership, with some compensation

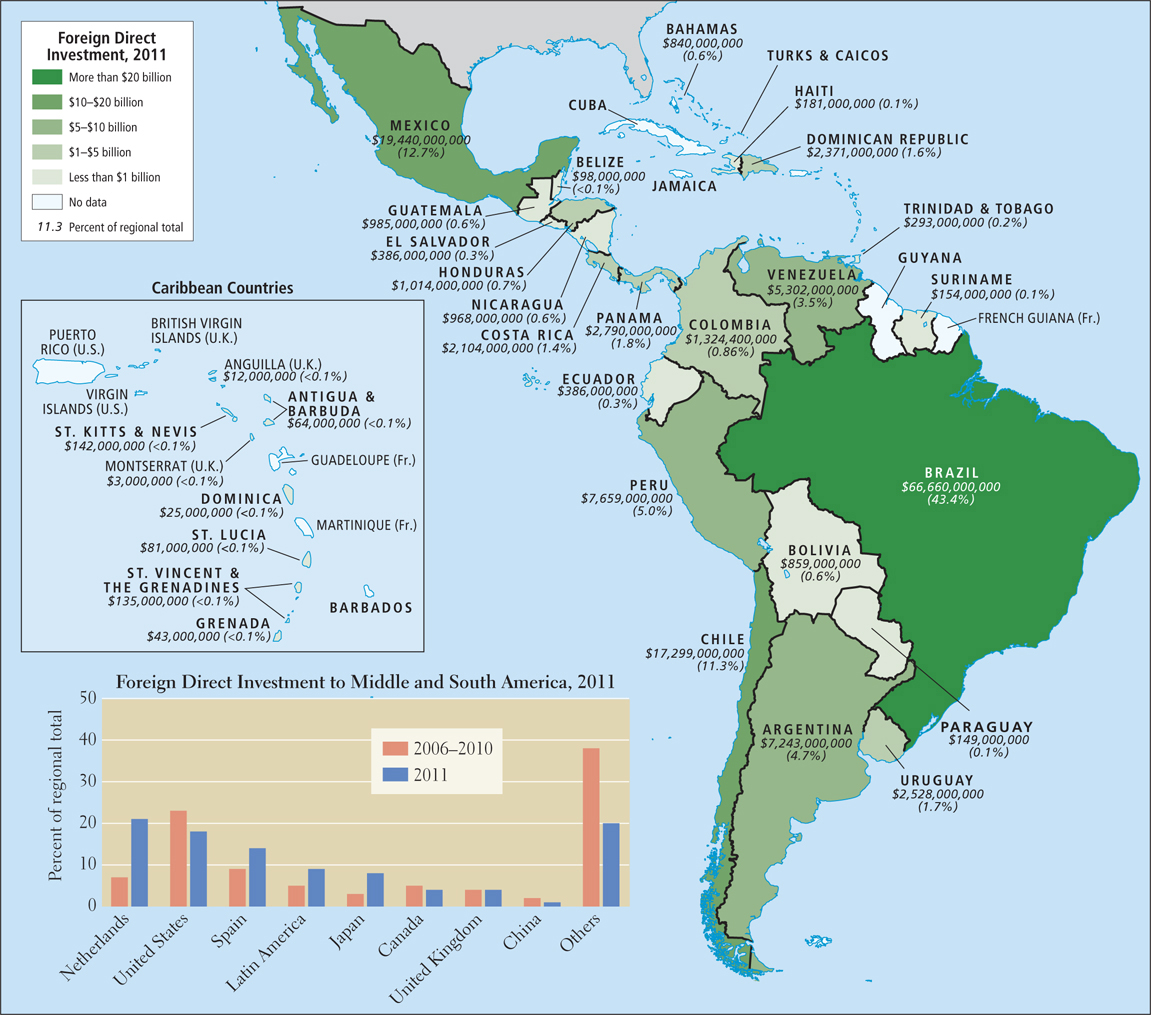

The Current Era of Foreign Direct Investment

The most recent development in this region is the emergence of several countries—

foreign direct investment (FDI) investment funds that come in to enterprises from outside the country

Brazil is part of a global foursome known as the BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These are emerging economic powers, rich in resources and poised for transformation into highly developed, highly productive powerhouses.

One measure of the region’s rising reputation as financially stable is the fact that in 2012, Christine Lagarde, director of the IMF, asked for help from Brazil, Mexico, and Peru in designing and funding a bailout package for overly indebted countries in the European Union—

Interest in investing in the region has risen significantly and shifted, as shown in the table in Figure 3.15. The Netherlands now plays the biggest role, primarily because it acts on behalf of a consortium of investor countries. Spain has had a major FDI role for a number of years. The absolute amounts invested by the United States are rising, but because of the strong interest of others, the U.S. proportion has decreased. China quietly invested in the region in relatively small ways for several decades, but recently it has increased its investments and appears to be most interested in buying or leasing (for an extended period) large swatches of agricultural land in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.

The Role of Remittances Migration for the purpose of supporting family members back home with remittances is an extremely important economic activity throughout this region (see further discussion later in this chapter). Each year, remittances amount to roughly double the U.S. foreign aid to the region. Most such remittance migrations are within countries. While the amounts of cash sent home are small, these remittances are crucial for families that may not have much other income.

One report (by geographer Dennis Conway and anthropologist Jeffrey H. Cohen) suggests that couples who migrate to the United States from indigenous villages in Mexico typically work at menial jobs and live frugally in order to save a substantial nest egg. Then they may return home for several years to build a house (usually a family self-

The Informal Economy

For centuries, low-

Regional Trade and Trade Agreements

The growth in international trade and foreign investment in the region, in part the result of SAPs, has been joined by growth in regional free trade agreements. Such agreements reduce tariffs and other trade barriers among a group of neighboring countries. The two largest free trade agreements within the region are NAFTA and UNASUR.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), established a free trade bloc in 1994, consisting of the United States, Mexico, and Canada—

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) a free trade agreement made in 1994 that added Mexico to the 1989 economic arrangement between the United States and Canada

UNASUR, a union of South American nations, was organized in May of 2008; it supersedes Mercosur and the Andean Community of Nations, two previous customs unions. The 12 member countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Venezuela) have nearly 400 million people, with a combined economy worth nearly $8 trillion per year. UNASUR appears to want to emulate the European Union in that it has adopted resolutions on a multitude of economic, political, military, immigration, and trade issues, not the least of which is to reduce disparities of wealth and opportunity.  62. MANY VENEZUELANS UNCERTAIN ABOUT CHÁVEZ’S TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY SOCIALISM

62. MANY VENEZUELANS UNCERTAIN ABOUT CHÁVEZ’S TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY SOCIALISM

UNASUR a union of South American nations that was organized in May of 2008; it supersedes Mercosur and the Andean Community of Nations, two previous customs unions

Mercosur a free trade zone created in 1991 that links the economies of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela to create a common market

The overall record of regional free trade agreements so far is mixed. While they have increased the amount of trade, the benefits of that trade usually are not spread evenly among regions or among all sectors of society. In Mexico, for instance, the benefits of NAFTA have gone mainly to the wealthy investors who are concentrated in the northern states that border the United States. There, the agreement facilitated the growth of maquiladoras by easing cross-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Contributions from the Informal Economy

Throughout this region, nearly everyone depends on the informal economy in some way, as either a buyer or a seller. Critics argue that informal workers are just treading water, making too little to ever expand their businesses significantly. Moreover, the bribes they have to pay to avoid arrest or fines are much less beneficial to the economy as a whole than the taxes paid by legitimate businesses. Work in the informal economy is also risky because there is no protection of workers’ health and safety, nor sick leave, retirement, or disability benefits (also often lacking in the formal economy). Nevertheless, the informal economy can be a lifesaver during times of economic recession. After a recession hit Peru in 2000, for example, 68 percent of urban workers were in the informal sector. They generated 42 percent of the country’s total GDP, mostly through street-

In some instances, the informal economy can serve as an incubator for new businesses that may expand, eventually providing legitimate jobs for family and friends. Those who work in the informal economy as well as those who migrate and send remittances are often unfairly overlooked as the major contributors to the economies of the region that they are.

The record of UNASUR is too short to be evaluated, but the shift in the global economy since UNASUR’s creation in 2008 may be creating conditions that will place this trade bloc in an advantageous position vis-

Rapid Regional Expansion of Internet Use Overall, Middle and South America are more advanced in terms of information technology than are many other developing regions of the world—

Mexico, with 36.9 percent of its population connected, recently launched a program to give its citizens access to training and higher education via the Internet (Figure 3.16). Similar efforts throughout the region are part of a long-

Food Production and Development

Food production throughout Middle and South America is shifting away from small-

For centuries, while people labored for very low wages on haciendas, the hacienda owners would at least allow them a bit of land to grow a small garden or some cash crops. SAPs encouraged a shift to green revolution agriculture, which was based on crops that could be exported for cash. This type of production, it was hoped, could help countries pay off debts faster. SAPs also made it easier for foreign multinational corporations such as Del Monte to use their financial resources to buy up many haciendas and other farms, converting them to plantations. This pattern of foreign corporate expansion into agriculture has continued into the modern FDI era. Many rural people have been forced off lands they once cultivated, and onto plantations, where they now work as migrant laborers for low wages, as the following story illustrates.

VIGNETTE

Aguilar Busto Rosalino used to work on a Costa Rican hacienda. He had a plot on which to grow his own food and in return worked 3 days a week for the hacienda. Since a banana plantation took over the hacienda, he rises well before dawn and works 5 days a week from 5:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., stopping only for a half-

Aguilar places plastic bags containing pesticide around bunches of young bananas. He prefers this work to his last assignment of spraying a more powerful pesticide, which left him and 10,000 other plantation workers sterile. He works very hard because he is paid according to how many bananas he treats. Usually he earns between $5.00 and $14.50 a day.

It is common practice for these banana operations to fire their workers every 3 months so that they can avoid paying the employee benefits that Costa Rican law mandates. Although Aguilar makes barely enough to live on, he has no plans to press for higher wages because if he did he would be put on a “blacklist” of people that the plantations agree not to hire. [Source: Andrew Wheat. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

Because of the moneymaking potential and political power of large-

Many areas have had large farms, such as the haciendas mentioned earlier, for centuries. These are now being converted to green revolution agriculture, similar to farms that can be found in the Midwestern United States. There is a wide belt of large-

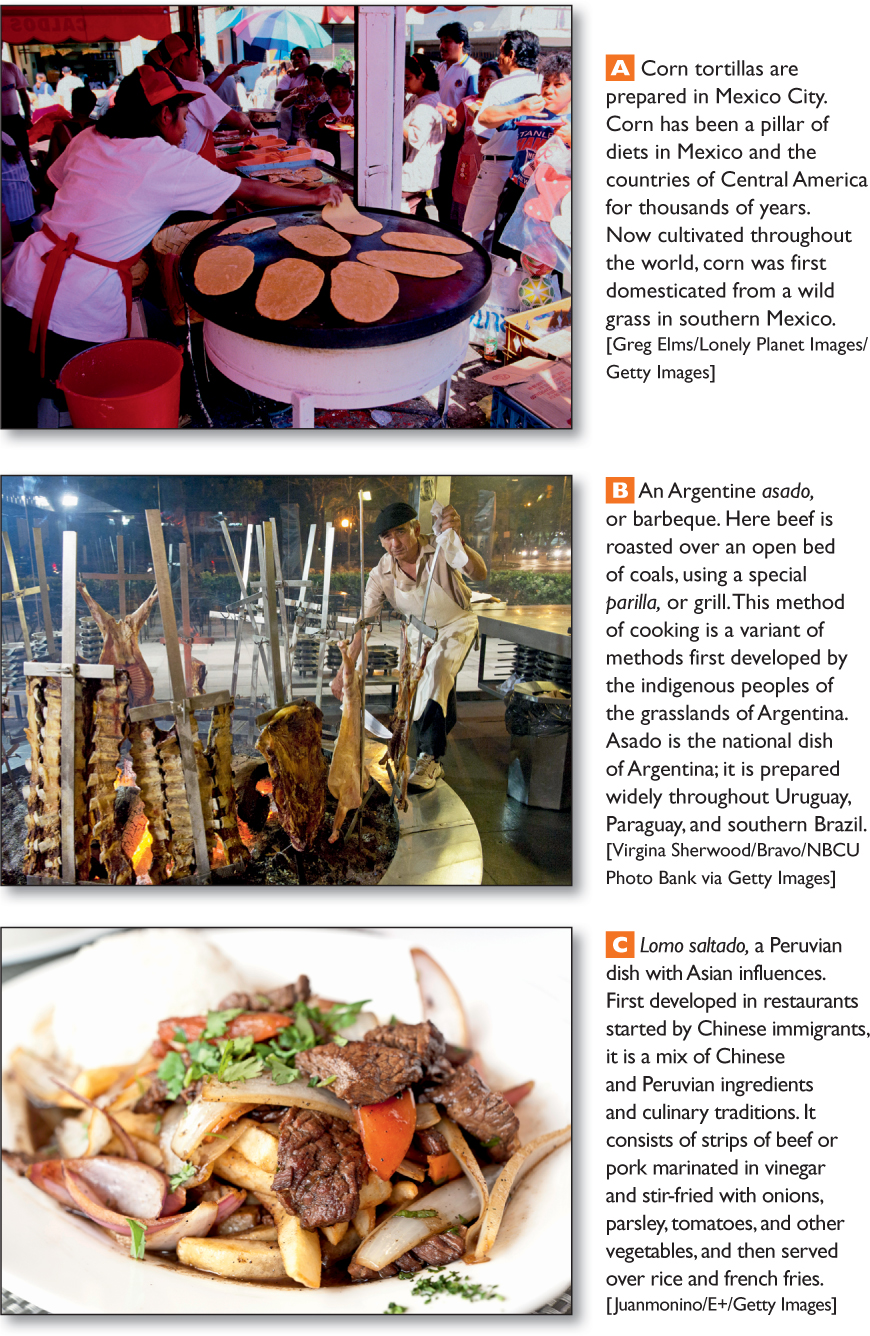

At a medium scale are zones of modern mixed farming (those that produce meat, vegetables, and specialty foods for sale in urban centers), located on large and small plots around most major urban centers. Figure 3.18 illustrates how the foodways of the area are based largely on indigenous plants (corn, potatoes, tomatoes) and methods of cooking (baking, grilling), and involve beef, pork, rice, seasonings, and cooking methods (frying) imported from Europe, Asia, and Africa.  57. HAITI’S RISING COST OF FOOD WORRIES AID GROUPS

57. HAITI’S RISING COST OF FOOD WORRIES AID GROUPS

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development The integration of this region with the global economy has left it with the widest gap between rich and poor in the world. Long-

term failures to address poverty, economic instability, and the flow of resources and money out of the region have resulted in many conflicts and inspired numerous efforts at reform. Nevertheless, in recent years several countries in this region have emerged as global economic leaders. Three phases of economic development—

extractive, import substitution industrialization (ISI), and structural adjustment programs (SAPs)—dominated the region into the twenty- first century. Since 1999, presidents who explicitly opposed SAPs have been elected in eight countries in the region: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Brazil is part of a global foursome known as the BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These are emerging economic powers, rich in resources and poised for transformation into highly developed, highly productive powerhouses.

Since the 1990s, free trade policies have been adopted in some industries, and regional trading blocs have been formed and re-

formed, with mixed results. Food production throughout this region is undergoing a shift away from small-

scale, often subsistence- level production toward large- scale, green revolution agriculture that is aimed at earning cash.