3.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

Under colonialism, a series of social structures evolved that guided daily life—

Cultural Diversity

The region of Middle and South America is culturally complex because many distinct indigenous groups were already present when the Europeans arrived, and then many cultures were introduced during and after the colonial period. From 1500 to the early 1800s, some 10 million people from many different parts of Africa were brought to plantations on the islands and in the coastal zones of Middle and South America. After the emancipation of African slaves in the British-

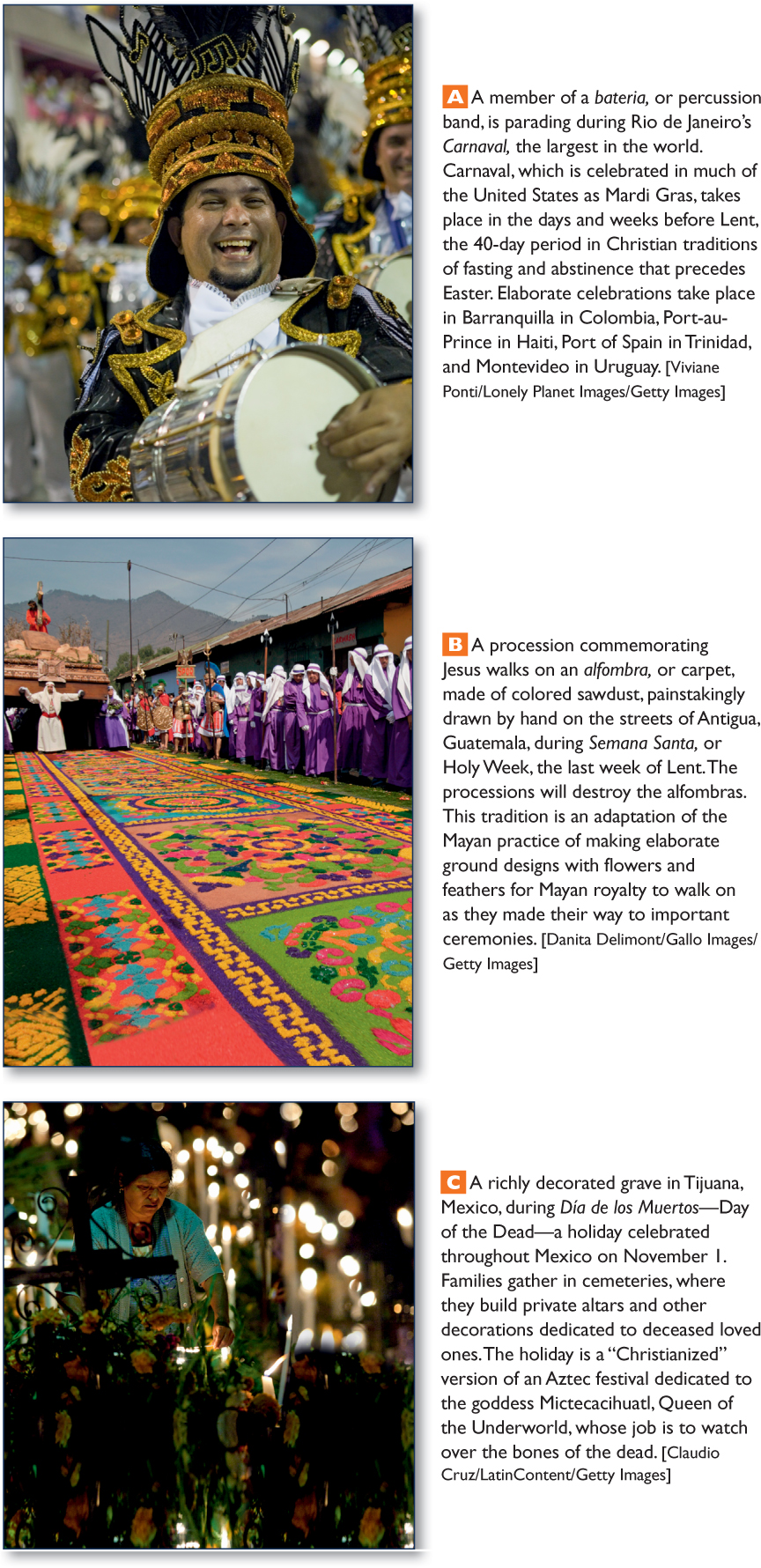

In the Caribbean and along the east coast of Central America as well as the Atlantic coast of Brazil, mestizos (people who have a mixture of African, European, and some indigenous ancestry) make up the majority of the population. Some of the most colorful festivals in the Americas, such as versions of Mardi Gras, known here as Carnival, are based on a melding of cultural practices from these three heritages (Figure 3.26A). In some areas, such as Argentina, Chile, and southern Brazil, people of Central European descent are also numerous. The Japanese, though a tiny minority everywhere in the region, increasingly influence agriculture and industry, especially in Brazil, the Caribbean, and Peru. Alberto Fujimori, a Peruvian of Japanese descent, campaigned on his ethnic “outsider” status to become president of Peru during a time of political upheaval.

In some ways, diversity is increasing as the media and trade introduce new influences from abroad. At the same time, the processes of acculturation and assimilation are also accelerating, thus erasing diversity to some extent as people adopt new ways. This is especially true in the biggest cities, where people of widely different backgrounds live in close proximity to one another.

acculturation adaptation of a minority culture to the host culture enough to function effectively and be self-

assimilation the loss of old ways of life and the adoption of the lifestyle of another culture

Race and the Social Significance of Skin Color People from Middle and South America, especially those from Brazil, often proudly claim that race and color are of less consequence in this region than in North America. They are only partially right. In all of the Americas, skin color is now less associated with status than in the past. By acquiring an education, a good job, a substantial income, the right accent, and a high-

Nevertheless, the ability to reduce the significance of skin color through one’s actions is not quite the same as race having no significance at all. Overall, those who are poor, less educated, and of lower social standing tend to have darker skin than those who are educated and wealthy. And while there are poor people of European descent throughout the region, most light-

The Family and Gender Roles

The basic social institution in the region is the extended family, which may include cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and more distant relatives. It is generally accepted that the individual should sacrifice many of his or her personal interests to those of the extended family and community and that individual well-

extended family a family that consists of related individuals beyond the nuclear family of parents and children

The arrangement of domestic spaces and patterns of socializing illustrate these strong family ties. Families of adult siblings, their mates and children, and their elderly parents frequently live together in domestic compounds of several houses surrounded by walls or hedges. Social groups in public spaces are most likely to be family members of several generations rather than unrelated groups of single young adults or married couples, as would be the case in Europe or the United States. A woman’s best friends are likely to be her female relatives. A man’s social or business circles will include male family members or long-

Gender roles in the region have been strongly influenced by the Roman Catholic Church. The Virgin Mary is held up as the model for women to follow through a set of values known as marianismo, which emphasizes chastity, motherhood, and service to the family. In this still-

marianismo a set of values based on the life of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, that defines the proper social roles for women in Middle and South America

Her husband, the official head of the family, is expected to work and to give most of his income to his family. Still, men have much more autonomy and freedom to shape their lives than women because they are expected to move about the larger community and establish relationships, both economic and personal. A man’s social network is considered just as essential to the family’s prosperity and status in the community as is his work.

There are very different sexual standards for males and females. While all expect strict fidelity from a wife to a husband in mind and body, a man is much freer to associate with the opposite sex. Males measure themselves by the model of machismo, in which manliness is considered to consist of honor, respectability, fatherhood, household leadership, attractiveness to women, and the ability to be a charming storyteller. Traditionally, the ability to acquire money was secondary to other symbols of maleness. Increasingly, however, a new, market-

machismo a set of values that defines manliness in Middle and South America

While a general inclination to keep all kinds of sexual relationships “in the closet” persists, over the last decade attitudes have begun to change, due in part to television dramas (known as telenovelas) that have explored many formerly taboo sexual issues, especially homosexuality. Respect for the rights of gays and lesbians has grown significantly in recent years; Argentina and Mexico City legalized same-

Religion in Contemporary Life

Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and indigenous beliefs are found across the region, but the majority of the people are at least nominal Christians, most of them Roman Catholic. While the Roman Catholic Church remains highly influential and relevant to the lives of believers, it has had to contend with popular efforts to reform it, as well as with increasing competition from other religious movements. From the beginning of the colonial era, the church was the major partner of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial governments. It received extensive lands and resources from colonial governments, and in return built massive cathedrals and churches throughout the region, sending thousands of missionary priests to convert indigenous people. The Roman Catholic Church encouraged these people to accept their low status in colonial society, to obey authority, and to postpone rewards for their hard work until heaven.

People throughout the region converted to the faith, some willingly and some only after the threats, intimidation, and torture of the Spanish Inquisition were brought to the Americas. Many indigenous people put their own spin on Catholicism, creating multiple folk versions of the Mass with folk music, more participation by women in worship services, and interpretations of Scripture that vary greatly from European versions. A range of African-

The power of the Roman Catholic Church began to erode in the nineteenth century in places such as Mexico. Populist movements, aimed at addressing the needs of the poor masses, seized and redistributed some church lands. They also canceled the high fees the clergy had been charging for simple rites of passage such as baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Over the years, the Catholic Church became less obviously connected to the elite and more attentive to the needs of poor and non-

populist movements popularly based efforts, often seeking relief for the poor

In the 1970s, a Catholic movement known as liberation theology was begun by a small group of priests and activists. They were working to reform the church into an institution that could combat the extreme inequalities in wealth and power common in the region. The movement portrayed Jesus Christ as a social revolutionary who symbolically spoke out for the redistribution of wealth when he divided the loaves and fish among the multitude. The perpetuation of gross economic inequality and political repression was viewed as sinful, and social reform as liberation from evil.

liberation theology a movement within the Roman Catholic Church that uses the teachings of Jesus to encourage the poor to organize to change their own lives and to encourage the rich to promote social and economic equity

The legacy of liberation theology is now fading. At its height in the 1970s and early 1980s, liberation theology was the most articulate movement for region- 79. POPE OPENS TOUR OF LATIN AMERICA IN BRAZIL

79. POPE OPENS TOUR OF LATIN AMERICA IN BRAZIL

Evangelical Protestantism has spread from North America into Middle and South America, and is now the region’s fastest-

evangelical Protestantism a Christian movement that focuses on personal salvation and empowerment of the individual through miraculous healing and transformation; some practitioners preach to the poor the “gospel of success”—that a life dedicated to Christ will result in prosperity for the believer

The movement is charismatic, meaning that it focuses on personal salvation and empowerment of the individual through miraculous healing and psychological transformation. Evangelical Protestantism is not hierarchical in the same way as the Roman Catholic Church, and there is usually no central authority; rather, there are a host of small, independent congregations led by entrepreneurial individuals who may be either male or female.

Perhaps two of the most important contributions of evangelical Protestantism are the focus (as in Umbanda and other African-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The region of Middle and South America is culturally complex because many distinct indigenous groups were already present when the Europeans arrived, and then many cultures were introduced during and after the colonial period.

The basic social institution in the region is the extended family, which may include cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and more distant relatives.

Gender roles in the region have been strongly influenced by the Catholic Church through the ideals of marianismo and machismo.

Evangelical Protestantism came to the region from North America and is now the fastest-

growing religious movement in the region, though Catholicism is still the dominant religion.