4.2 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

PHYSICAL PATTERNS

Europe’s physical geography is shaped by its many peninsulas which reach into surrounding oceans and seas, and by its variable landforms, all of which affect the region’s climates and vegetation.

Landforms

Although European landforms are fairly complex, the basic pattern is mountains, uplands, and lowlands, all stretching roughly west to east in wide bands. As you can see in Figure 4.1 (in the map and in photo A), Europe’s largest and highest mountain chain, the Alps, runs west to east through the middle of the continent, from southern France through Switzerland and Austria. The Alps extend into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and curve southeast as the Carpathian Mountains into Romania. This network of mountains is mainly the result of pressure from the collision of the northward-

South of the main Alps formation, lower mountains extend into the peninsulas of Iberia and Italy and along the Adriatic Sea through Greece to the southeast. The northernmost mountainous formation is shared by Scotland, Norway, and Sweden. These northern mountains are old (about the age of the Appalachians in North America) and have been worn down by glaciers and millions of years of erosion.

Extending northward from the central Alpine zone is a band of low-

Crossed by many rivers and holding considerable mineral deposits, the coastal lowland of the North European Plain is an area of large industrial cities and densely occupied rural areas. Over the past thousand years, people have transformed the natural seaside marshes and vast river deltas into farmland, pastures, and urban areas by building dikes and draining the land with wind-

The rivers of Europe link its interior to the surrounding seas. Several of these rivers are navigable well into the upland zone, and Europeans have built large industrial cities on their banks. The Rhine carries more traffic than any other European river, and the course it has cut through the Alps and uplands to the North Sea also serves as a route for railways and motorways (see Figure 4.1D). The area where the Rhine flows into the North Sea is considered the economic core of Europe. Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port, is located here. The Danube River, larger and much longer than the Rhine, flows southeast from Germany, connecting the center of Europe with the Black Sea. As the European Union expands to the east, the economic and environmental roles of the Danube River basin, including the Black Sea, are getting more attention (see Figure 4.1E).

Vegetation and Climate

Nearly all of Europe’s original forests are gone, some for more than a thousand years. Today, forests with very large and old trees exist only in scattered areas, especially on the more rugged mountain slopes (see Figure 4.1A, B) and in the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Forests are intensively managed and are regenerating on abandoned farmland. Although forests now cover about one-

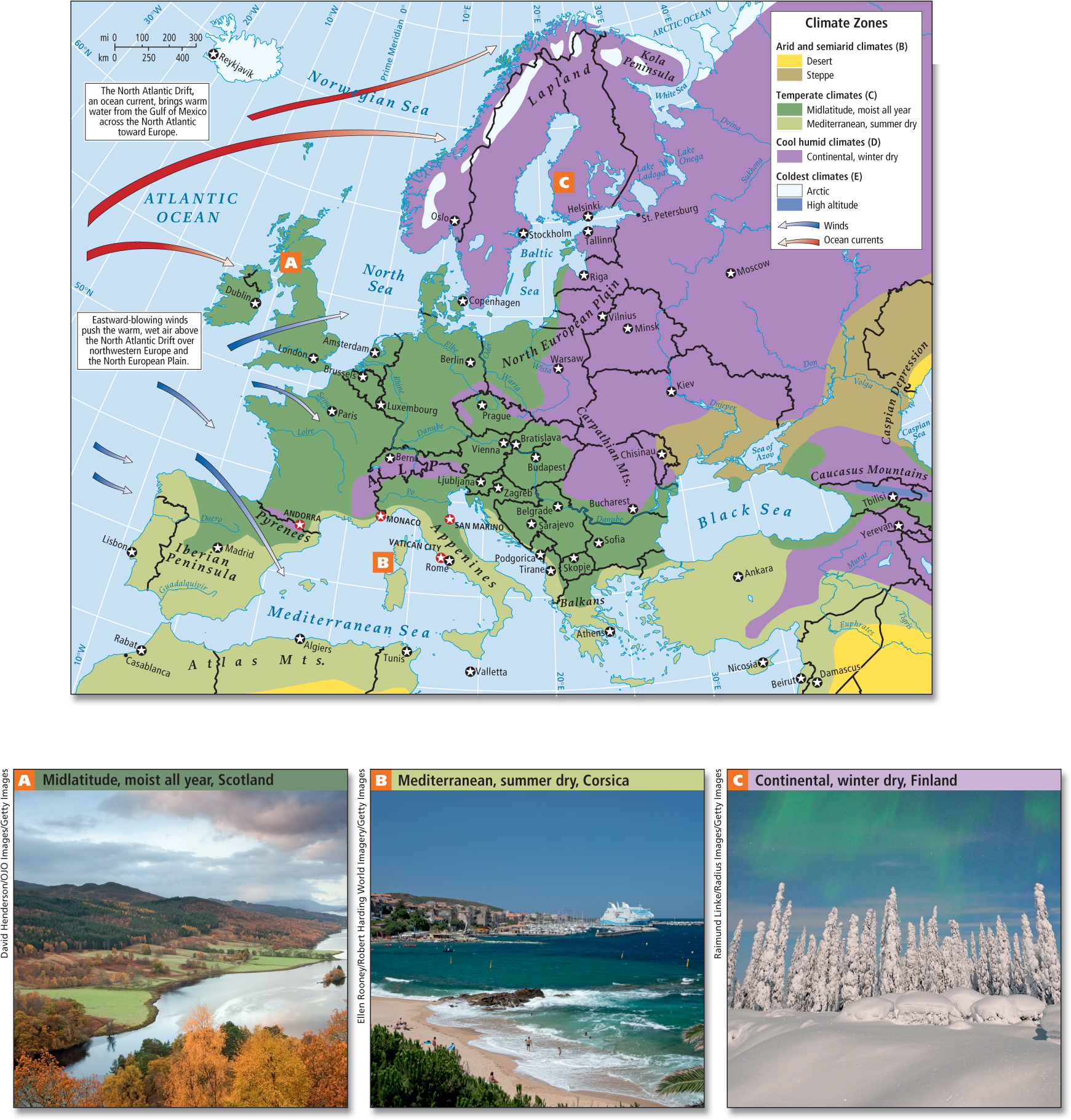

Europe has three main climate types: temperate midlatitude, Mediterranean, and continental (Figure 4.4). The temperate midlatitude climate, characterized by year-

temperate midlatitude climate as in south-

A broad, warm-

North Atlantic Drift the easternmost end of the Gulf Stream, a broad warm-

Farther to the south, the Mediterranean climate prevails—

Mediterranean climate a climate pattern of warm, dry summers and mild, rainy winters

In Central Europe, without the moderating influences of the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, the climate is more extreme. In this region of continental climate, summers are fairly hot, and the winters become longer and colder the farther north or deeper into the interior of the continent one goes (see Figure 4.4C). Here, houses tend to be well insulated with small windows, low ceilings, and steep roofs that can shed snow. Crops must be adapted for much shorter growing seasons, and include corn and other grains plus fruit trees and a wide variety of vegetables adapted to the cold, especially root crops and cabbages.

continental climate a midlatitude climate pattern in which summers are fairly hot and moist, and winters become longer and colder the deeper into the interior of the continent one goes

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Europe is a region of peninsulas upon peninsulas.

Europe has three main landforms: mountain chains, uplands, and the vast North European Plain.

Europe has three principal climates: the temperate midlatitude, the Mediterranean climate, and the continental climate.