4.5 GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: In order to better compete in the global economy, the EU has shifted labor-

The European Union uses a number of economic development strategies designed to ensure its ability to compete with the United States, Japan, and the developing economies of Asia, Africa, and South America. To increase Europe’s export potential, the EU has focused on lowering the cost of producing goods in Europe. One strategy is to shift labor-

Europe’s Growing Service Economies

As industrial jobs have declined across the region, most Europeans (about 70 percent) have found jobs in the service economy. Services, such as the provision of health care, education, finance, tourism, and information technology, are now the engine of Europe’s integrated economy, drawing hundreds of thousands of new employees to the main European cities. For example, financial corporations that are located in London and serve the entire world play a huge role in the British economy. Many multinational companies are headquartered in London in part to take advantage of the city’s financial sector.

Opportunities for economic growth provided by Europe’s highly educated population have transformed the service sector, with almost 40 percent of all employment in the EU now in knowledge-

While the EU is making little effort to compete with Asian companies on labor costs, it is now investing more in research and development to better compete with U.S. companies. While the EU lagged behind North America in the development and use of personal computers and the Internet, it still leads the world in cell phone use. The information economy is especially advanced in North and West Europe, though some in South European countries have pioneered high-

A major component of Europe’s service economy is tourism. Europe is the most popular tourist destination in the world, and one job in eight in the European Union is related to tourism. Tourism generates 13.5 percent of the EU’s GDP and 15 percent of its taxes, although this varies with global economic conditions. Europeans are themselves enthusiastic travelers, frequently visiting one another’s countries to attend local festivals (Figure 4.14) as well as traveling to many distant locations throughout the world. This travel is made possible by the long paid annual vacations—

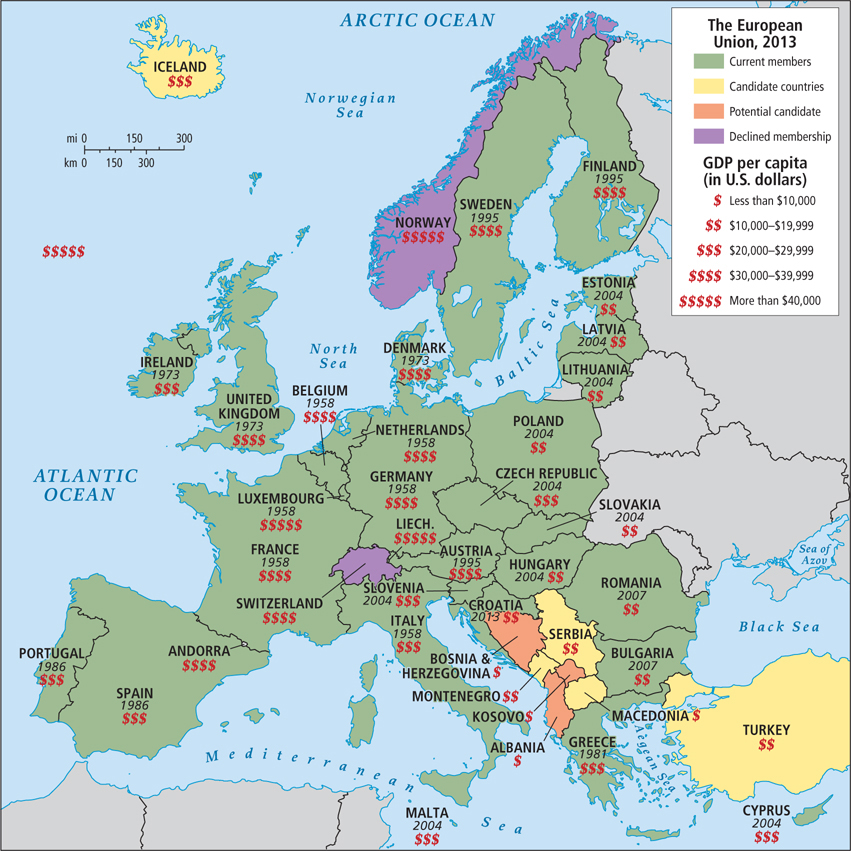

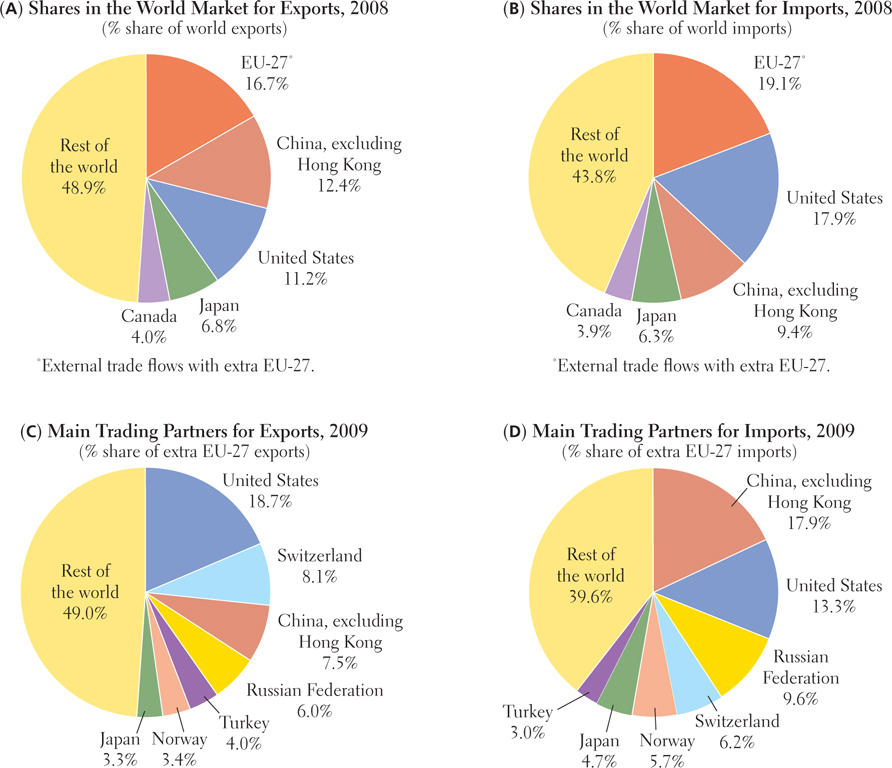

Economic Comparisons of the EU and the United States The EU economy now encompasses more than 500 million people (out of a total of 540 million in the whole of Europe)—roughly 200 million more than live in the United States. Collectively, the EU countries are wealthy, with a joint economy slightly larger than that of the United States, making the EU the largest economy in the world and one that exerts a powerful influence on the global trading system (Figure 4.15). Even so, trade between countries within the EU amounts to about twice the monetary value of trade between the EU as a whole and the outside world.

In contrast to the United States, which usually imports far more than it exports—

Careful regulation of EU economies contributes to generally slower economic growth than in the United States. These regulations also make the European Union more resilient to global financial crises, such as the crisis beginning in 2008, largely because of stronger control (than in the United States) of the banking industry and financial markets.

Economic Integration and a Common Currency Economic integration has addressed a number of problems in Europe. Individual European countries have relatively small populations, which means that they have smaller internal markets for their products. As a result, their companies earn lower profits than those in large countries. The European Union solved this problem by joining European national economies into a common market. Companies in any EU country now have access to a much larger market and can potentially make larger profits through economies of scale (reductions in the unit costs of production that occur when goods or services are efficiently mass-

economies of scale reductions in the unit cost of production that occur when goods or services are effi ciently mass produced, resulting in increased profits per unit

The official currency of the European Union is the euro (є). Eighteen EU countries now use the euro: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Countries that use the euro have a stronger voice in the creation of EU economic policies, and the use of a common currency greatly facilitates trade, travel, and migration within the European Union. All non-

euro the offi cial (but not required) currency of the European Union as of January 1999

The Euro and Debt Crises

In recent years, there have been major challenges to the euro, most significantly in the form of a debt crisis that has tested the mechanisms that governments use to maintain economic stability. The debt crisis first emerged in Greece, where government spending was significantly outpacing tax revenues. This was compounded by the growth of Greece’s trade deficit during the global economic slowdown starting (in Europe) in 2008, which affected tourism and reduced demand for Greece’s exports. Similar conditions in other countries led to similar debt crises in other euro zone countries, especially Ireland, Spain, and Portugal.

Normally, governments respond to high levels of debt by borrowing from other countries and then reducing the value of their currency, relative to that of the lenders, which makes these debts easier to pay. However, this was not an option for any member of the euro zone because no country could by itself manipulate the value of the euro. The EU has the European Central Bank (ECB), which controls the value of the euro, but it is strongly influenced by the larger euro zone economies, such as those of Germany and France. Banks in these countries had loaned large amounts of money to Greece and the other indebted governments of the euro zone, and they would lose money if the value of the euro declined. However, because all the economies of the euro zone were threatened by the crises, Germany and France had to act.

In addition to making large, inexpensive loans available to Greece and the other indebted governments through the ECB over the short term, the European Union, with crucial support by Germany and France, developed longer-

Food Production and the European Union

Concerns about food security in Europe have led to heavily subsidized and regulated agricultural systems. Subsidies to agricultural enterprises account for more than 40 percent of the budget of the European Union. Although large-

Food security is especially important to Europeans, probably because stories of post–

The Common Agricultural Program (CAP) The drastic decline of labor and land in farming has had an emotional effect on Europeans, who see it as endangering their cultural heritage and their goal of food self-

Common Agricultural Program (CAP) an EU program, meant to guarantee secure and safe food supplies at affordable prices, that places tariffs on imported agricultural goods and gives subsidies to EU farmers

The CAP has long been criticized for undermining its own goals with its use of tariffs on imported agricultural goods and for giving subsidies (in this case, payments to farmers) to underwrite the costs of food production. Tariffs effectively raise food costs for millions of EU consumers. The subsidies tend to favor large, often corporate-

subsidies monetary assistance granted by a government to an individual or group in support of an activity, such as farming, that is viewed as being in the public interest

Protective agricultural policies like tariffs and subsidies—

The Growth of Corporate Agriculture and Food Marketing As small family farms disappear in the European Union—

The move toward corporate agriculture is strongest in Central Europe. When Communist governments gained power in the mid-

A CASE STUDY

Green Food Production in Slovenia

During the Communist era, Slovenia was unlike most of the rest of Central Europe in that the farms were not collectivized. As a result, the average farm size is just 8.75 acres (3.5 hectares). Although Slovenia has plenty of rich farmland, as standards of living have risen, it has become a net importer of food. Nonetheless, Slovenia’s new emphasis on private entrepreneurship, combined with a growing demand throughout Europe for organic foods, has encouraged some Slovene farmers to carve out an organic niche for themselves, fi rst in local markets and eventually as exporters. The case of Vera Kuzmic is illustrative (Figure 4.17).

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Question 4.14

How can you tell that Vera is involved in small-

VIGNETTE

Vera Kuzmic (a pseudonym) lives 2 hours by car south of Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital. For generations, her family has farmed 12.5 acres (5 hectares) of fruit trees near the Croatian border. In the economic restructuring that took place after Slovenia became independent in 1991, Vera and her husband lost their government jobs. The Kuzmic family decided to try earning its living in vegetable-

Vera secured market space in a suburban shopping center in Ljubljana, where she and one employee maintained a small vegetable and fruit stall (see Figure 4.17). Her produce had to compete with less expensive, Italian-

Anticipating the challenges to come, the Kuzmics’ daughter Lili completed a marketing degree at the University of Ljubljana. The family incorporated their business and Lili is now its Ljubljana-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development In order to better compete in the global economy, the EU has shifted labor-

intensive industries from western Europe, where wages are high, to the relatively poorer, lower- wage member states of Central Europe. Growth in services has made up for some of the loss of industrial jobs in western Europe, though the unemployment rate is high in some countries. The EU continues to struggle to integrate the economies of its member states, especially those that use the EU’s common currency, the euro. Collectively, the EU countries are wealthy, with a joint economy slightly larger than that of the United States, making the European Union the largest economy in the world.

In recent years, there have been major challenges to the euro, most signifi cantly in the form of a debt crisis that has tested the mechanisms that governments use to maintain economic stability.

Concerns about food security in Europe have led to heavily subsidized and regulated agricultural systems. Subsidies to agricultural enterprises account for more than 40 percent of the budget of the European Union.