5.3 ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 1

Environment: Economic development has taken precedence over environmental concerns in Russia and the post-

Soviet ideology held that nature was the servant of industrial and agricultural progress, and that humans should dominate nature on a grand scale. While this sentiment was common throughout much of the world at the time of the formation of the USSR, it does seem to have been taken further here than elsewhere. Joseph Stalin, leader of the USSR from 1922 to 1953 and a major architect of Soviet policy, is famous for having said, “We cannot expect charity from Nature. We must tear it from her.” During the Soviet years, huge dams, factories, and other industrial facilities were built without regard for their effect on the environment or on public health. Russia and the post-

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 5.2

A What is the life expectancy for men in Norilsk?

Question 5.3

C Why was Pripyat evacuated?

Question 5.4

D In addition to oil pollution, from what other form of pollution has the Arctic portion of this region suffered?

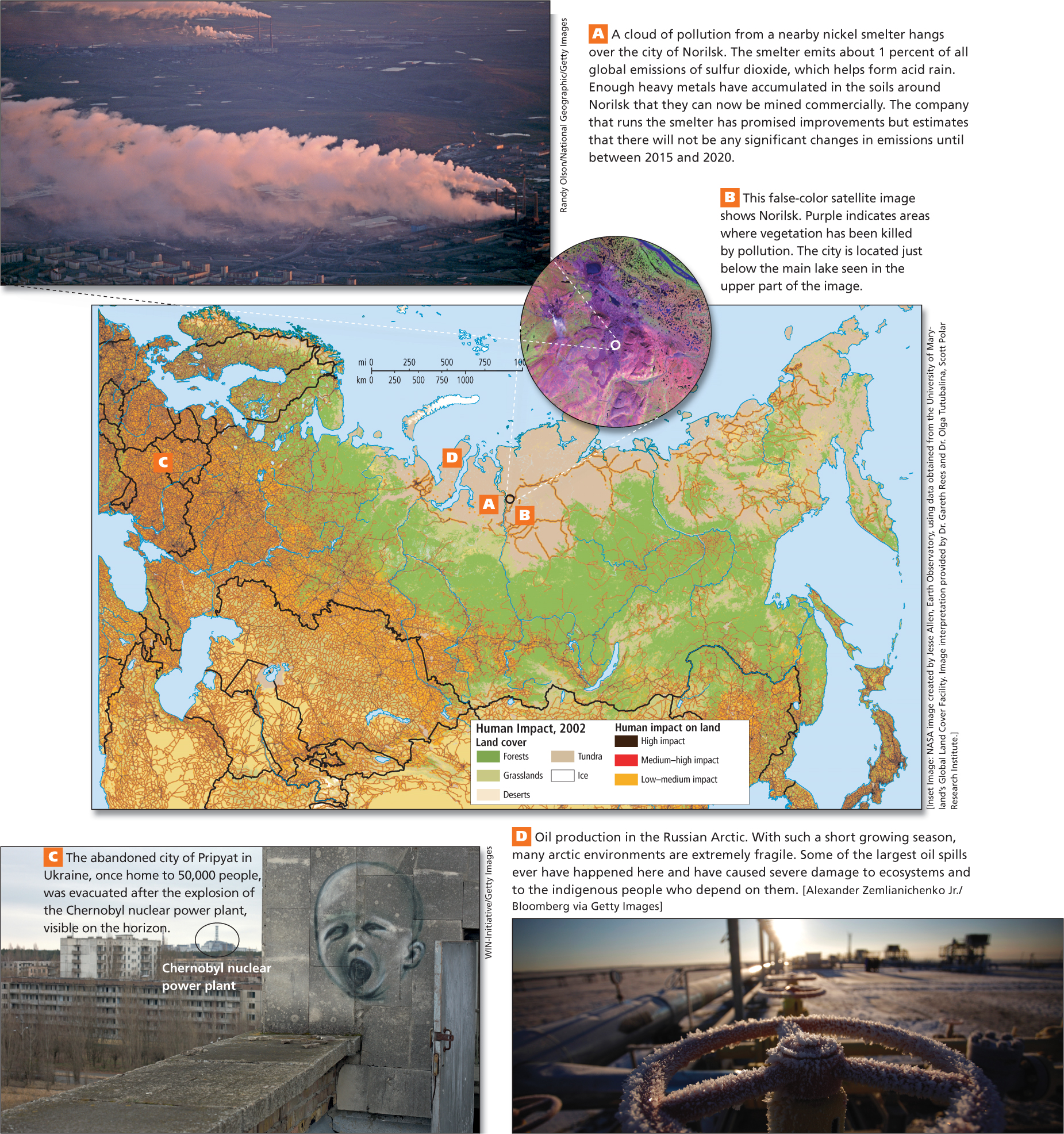

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the region’s governments, beset with myriad problems, have been both reluctant to address environmental issues and incapable of doing so. As one Russian environmentalist put it, “When people become more involved with their stomachs, they forget about ecology.” Pollution controls are complicated by a lack of funds and by an official unwillingness to correct past environmental abuses. Figure 5.6 shows just a few examples of human impacts on the region’s environment, most of which are related to ongoing industrial pollution (as in Norilsk, in Figure 5.6A, B), nuclear contamination (as in Pripyat, Ukraine, in Figure 5.6C), or the extraction of fossil fuels. The sale of oil and gas on the global market is now a major source of income for Russia and several of the post-

Urban and Industrial Pollution

Urban and industrial pollution was often ignored during Soviet times as cities expanded quickly—

It is often difficult to link urban pollution directly to health problems because the sources of contamination are multiple and difficult to trace. Such nonpoint sources of pollution include untreated automobile exhaust, raw sewage, and agricultural chemicals that drain from fields into water supplies. In all urban areas of the region, air pollution resulting from the burning of fossil fuels is skyrocketing as more people purchase cars and as the industrial and transport sectors of the economy continue to grow.

nonpoint sources of pollution diffuse sources of environmental contamination, such as untreated automobile exhaust, raw sewage, and agricultural chemicals that drain from fields into water supplies

Some cities were built around industries that produce harmful by-

Nuclear Pollution

Russia and the post- 278. SAFETY AT THE CENTER OF NUCLEAR POWER OPERATIONS WORLDWIDE

278. SAFETY AT THE CENTER OF NUCLEAR POWER OPERATIONS WORLDWIDE

When the Soviet Union collapsed, many of the post-

On the positive side, Kazakhstan’s government has disarmed the nuclear warheads that it inherited from the Soviet Union and has worked with U.S. authorities to safeguard its remaining nuclear weapons material. Kazakhstan plans to use its nuclear technology to become a global player in the nuclear energy sector. It is already the single biggest producer of uranium in the world, generating 35 percent of the global production total.

In addition to mining and exporting the raw material, Kazakhstan’s government wants to produce nuclear fuel both for global markets and domestic nuclear power plants and to develop commercial repositories for radioactive waste from other countries. However, the global appetite for nuclear expansion remains uncertain after the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan, and no reliably safe system has yet been found for storing nuclear waste until it is no longer radioactive. Environmental and human rights NGOs have raised strong opposition, pointing to the region’s poor environmental track record. Kazakhstan’s population may also be suspicious of nuclear power because they have lived for so long with land poisoned by radioactive waste.

The Globalization of Resource Extraction and Environmental Degradation

Russia and the post-

Despite obvious environmental problems, cities like Norilsk (see Figure 5.6A), which sits on huge mineral deposits, continue to attract investment crucial to the new Russian economy. The area is rich in nickel—

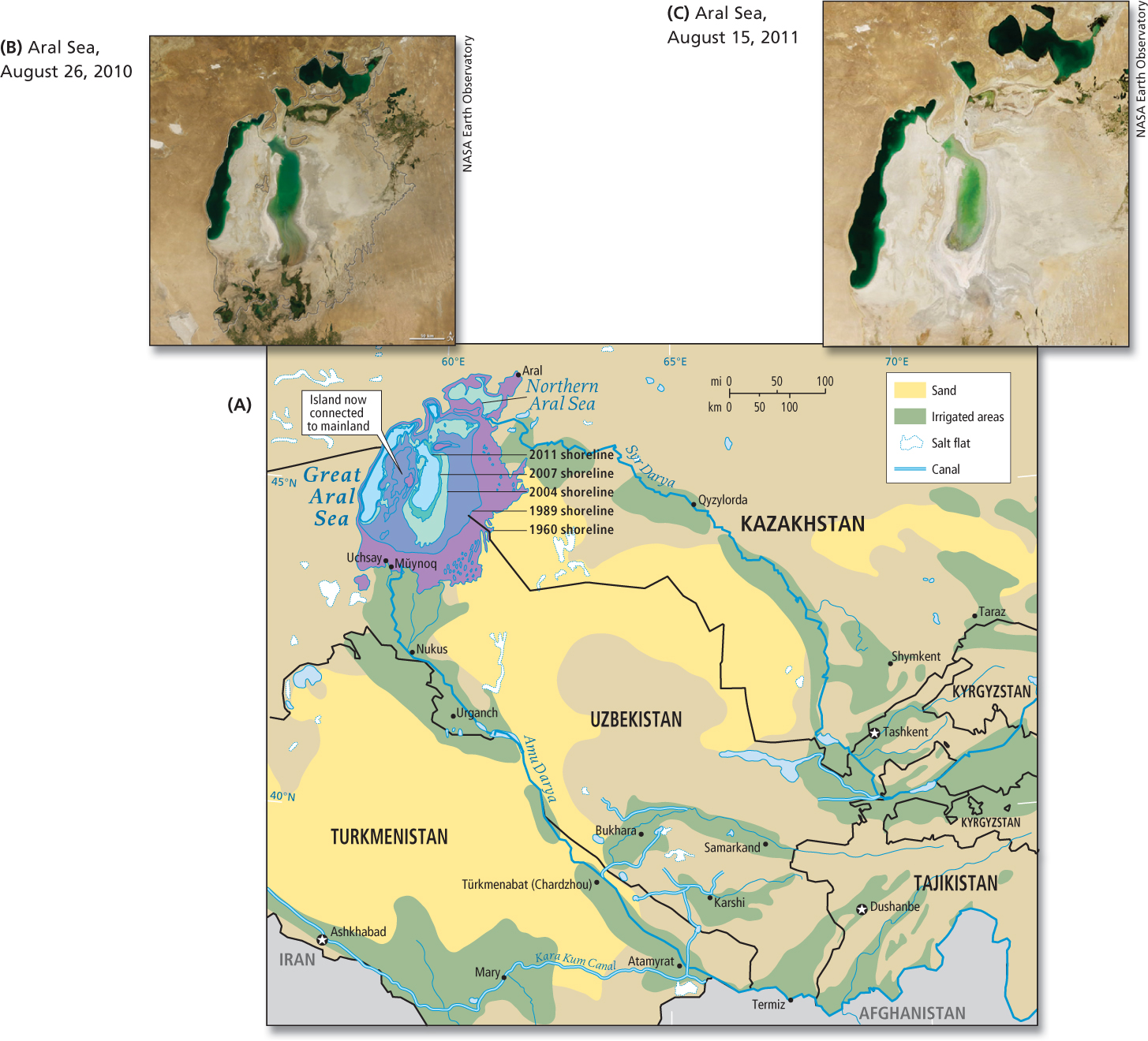

Rivers, Irrigation, and the Loss of the Aral Sea To the south of Russia in the Central Asian states, the landlocked Aral Sea, once the fourth-

In the 1960s, the Soviet leadership ordered that the two rivers be diverted to irrigate millions of acres of cotton in naturally arid Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. So much water was consumed by these projects that within a few years, the Aral Sea had shrunk measurably (Figure 5.7A). By the early 1980s, no water at all from the two rivers was reaching the Aral Sea, and by 2001, the sea had lost 75 percent of its volume and had shrunk into three smaller lakes. The region’s huge fishing industry, which accounted for one-

NASA Earth Observatory

The shrinkage of the Aral Sea has caused many human health problems. Winds that sweep across the newly exposed seabed pick up salt and chemical residues, creating poisonous dust storms. At the southern end of the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan, 69 percent of the people report chronic illnesses caused by air pollution, a lack of clean water, and underdeveloped sanitation.

Efforts to increase water flows to the Aral Sea have been hampered by politics because the now- 107. DYING SEA MAKES COMEBACK

107. DYING SEA MAKES COMEBACK

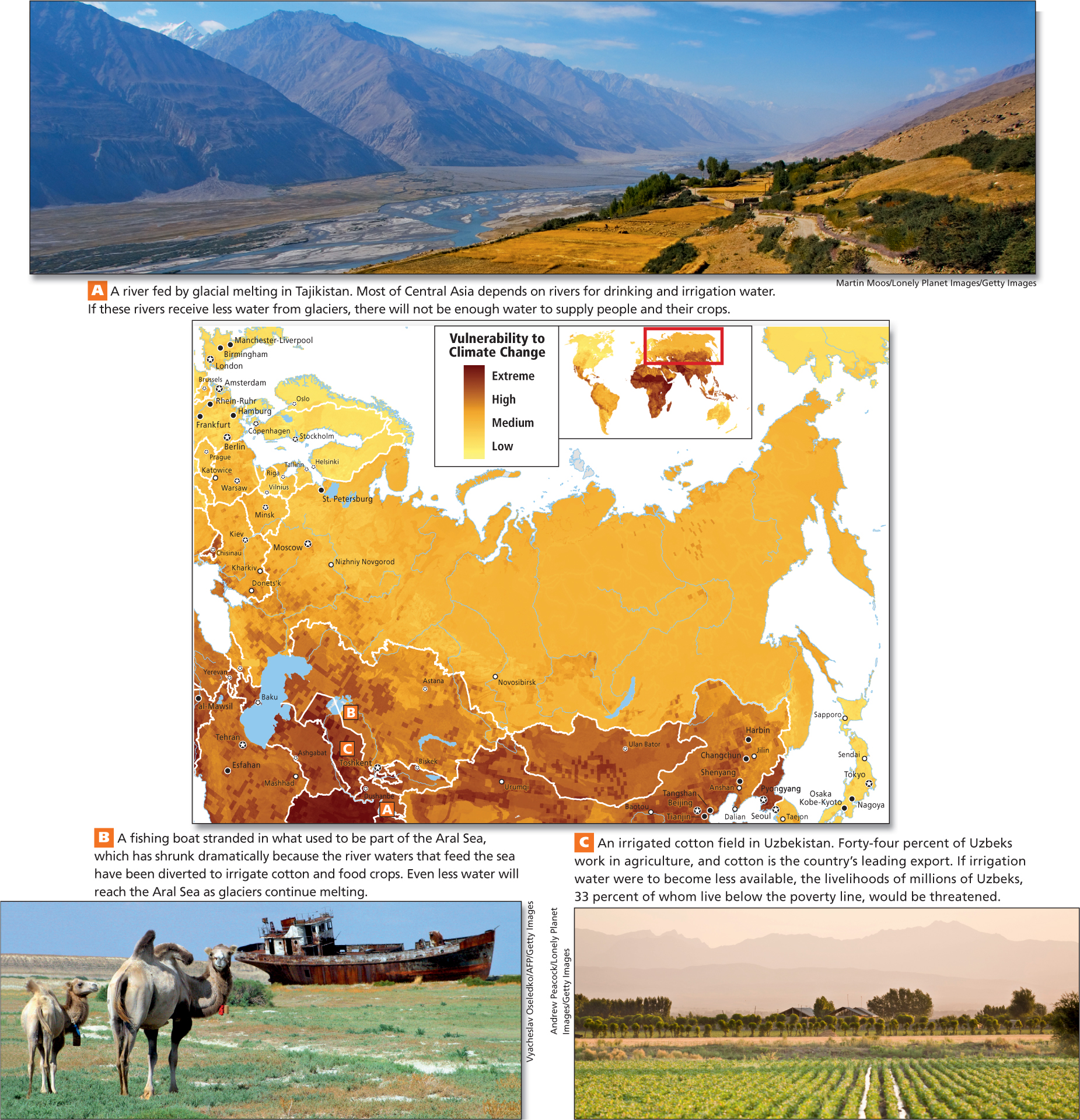

Climate Change

Climate change is an issue in this region for many reasons. Although high levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases are produced here, Russia’s forests play a major role in absorbing global CO2. And while portions of the region are only somewhat vulnerable to the negative effects of a changing climate (shown on the map in Figure 5.8), Central Asia, which is prone to drought and water scarcity, has high to extreme levels of vulnerability.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 5.5

A Why would rivers like the one in this photo receive less water over the long term due to climate change?

Question 5.6

B What major resource did the Aral Sea once provide in abundance?

Question 5.7

C Why would a decline in Uzbekistan’s cotton industry hurt the country’s economy?

Even though its CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions have declined since the Soviet era, Russia still has the fifth-

Russia has shown some willingness to limit its own emissions by, for example, signing international treaties, such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Copenhagen Accord, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Such treaties, however, use 1990 as a baseline for emissions. Russia’s compliance with international targets to reduce greenhouse emissions is largely an outcome of the country’s post-

Central Asia is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change because of its dependence on water from rivers that are fed by glaciers in the Pamirs and other mountains in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (see Figure 5.8). In recent decades, the glaciers have shrunk because of more extreme temperature ranges and decreases in rain and snowfall. In this area, most precipitation falls in the mountains in the winter and spring. The glaciers act as water-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Better Times Ahead?

While environmental pollution remains serious throughout this region, recent surveys suggest that pro-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 1

Environment Economic development has taken precedence over environmental concerns in Russia and the post-

Soviet states for decades, resulting in numerous environmental problems such as severe pollution of the air and water by toxic industrial waste. This region’s contribution to climate change is increasing as more people use automobiles for transportation. In parts of this region, food production systems and water resources are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Urban and industrial pollution was often ignored during Soviet times as cities expanded quickly—

with workers flooding in from the countryside— to accommodate the new industries that often generated lethal levels of pollutants. The world’s worst nuclear disaster occurred in Ukraine in 1986, when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded, severely contaminating a vast area in northern Ukraine, southern Belarus, and Russia.

Massive water diversions from rivers that once fed the Aral Sea began in the 1960s when the Soviet leadership ordered millions of acres to be irrigated for cotton production in naturally arid Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Central Asia is especially vulnerable to climate change, given its dependence on irrigated agriculture that uses water from rivers fed by glacial melt.